DIRECTOR, EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE

ON August 19, 1953 there appeared in the daily paper of Bad Mergentheim, Germany, a headline which read: "They came from America and they were four." This strange and somewhat untabloid banner heralded a novel and curious experiment in international relations sent out by Dartmouth College.

Four students, all members of the German language club (Germania), went to Germany to present a German play in German. Behind this project lay the double objective of education and the strengthening of the pronunciation of German for the students themselves. It soon became evident that a third objective, even more important, would be achieved by this visit: that of international understanding and friendship. This was best explained by one reviewer who wrote in the Tauber Zeitung, also of Bad Mergentheim: "In performing German plays in German in the United States these students strengthen the cultural bonds of understanding between the two countries. If it is realized that German is one of the hardest languages for foreigners to speak, the accomplishment of these American students in the handling of pronunciation and emotion is magnificent and the long and cordial rounds of applause that greeted them were justly deserved."

Behind this review of a performance fry four American boys in Germany lay years of preparation. Germania of Dartmouth College has been in the business of producing German plays in German for a long time. For a full 25 years Prof. Stephan J. Schlossmacher has drilled casts into excellent German speech and emotions culled from the texts of Schiller, Goethe, Kleist, Lessing, Hauptmann and a host of other great and lesser German dramatists. The Hanover audiences that saw these plays year after year sat doggedly through all the Teutonic emotional assaults made on them. Sturm und Drang alternated, somewhat too rarely it seemed, with comedy. For many years it was an unusual play that ended with a full cast unhampered with death or starvation. One play that is remembered had its heroine gathered to heaven amid throngs of Angels. Although some in the audience noted the similarity of this demise to that of Little Eva, they were also aware that here the similarity stopped. Hannele'sHimmelfahrt was no Uncle Tom's Cabin. Through all this Dr. Schlossmacher moved between periods of high excitement and desperate calm. It was obvious from the start that despite the terrors of production the German play was the thing.

Hanover audiences have long since been accustomed to his familiar figure, at once benign and temperamental. It is refreshing here to have an impression of him from one of his fellow countrymen, a German dramatic critic writing in the Frankische Nachrichten: "He must be between 60 and 65, this paternal and inspiriting director and caretaker of these Dartmouth College Germania players who are, at the moment, performing the play Durst. Despite his snowy locks there is underneath a youthful joviality that makes him young among the young, able to divest himself of his professorial dignity when he is working intimately with them." This estimate is inaccurate as to age (Dr. Schlossmacher is much younger) but it is perceptive in its estimate of the man.

Very early in the history of Germania, which he founded, he became aware that in these German productions he had a commodity that was unusual and which might be helpful to others even beyond the bounds of Hanover. In the early 1930s a Professor from Middlebury, after seeing one of the plays at Dartmouth, invited Germania to bring the production to his college. This was the beginning and it grew to a yearly tour which has been enlarged, on occasion, to include Harvard, Williams, and other New England colleges. The interest of Professor Graff of McGill University took the troupe to Montreal and even farther into other sections of Canada. Some of the Canadian performances were at colleges and universities and others before German immigrant communities settled since the last war.

It was natural then, after this taste of international trouping, that Germania should look far afield ... to the very home of the language and culture ... Germany itself.

It has been Dr. Schlossmacher's routine to spend some part of each summer in Germany and during his visit to his native land in 1952 he began to sound out a number of universities and spas as to the acceptability of this enlarged tour. Persuasive though he is, some of the professors and theatre proprietors who were questioned about it must have wondered what sort of performance four young Americans could achieve in a German play in Germany. Nevertheless the results of this informal poll were encouraging enough for Germania to proceed to plan the tour. The play selected was Durst (Thirst) by Rutenborn, a contemporary German work. The plot concerned four British soldiers during the desert campaign of World War II. In keeping with the established Sturm and Drang motif all four characters die. Nevertheless the choice was excellent from several points of view; the cast was entirely male, the costumes were simple uniforms, and all that was required in the way of staging was a flat floor with neutral drapes and dim lighting effects. This was rehearsed and performed in Hanover and taken on the New England and Canadian tour to prepare the cast for the European venture.

Much more than rehearsals went into the planning of this tour. Germania itself raised $600 toward expenses. Each member of the cast paid his own transportation and an alliance was established with the "Experiment in International Living" to provide bed and board during the trip. One of the students characterized this enthusiastically as "a home away from home." It was hoped that additional expense money might be obtained from the sale of tickets at the box offices where the play was presented in Germany. Although this source of income was comparatively small, it helped.

Once in Germany a pattern was established. Between .performances the members of the cast stayed with German families or travelled about into other portions of Germany not covered by the tour schedule. A few days prior to each performance the cast reassembled and rehearsed and then presented the play. As a general rule after each presentation the cast was feted at a reception. During rehearsals at the University of Heidelberg, for instance, they were entertained by Colonel John T. Barrett 31, on duty there with the U.S. Army.

Throughout the tour their progress and abilities were assessed by almost every newspaper in each of the cities they visited. These "notices" betray amazement in every case. Coupled with this is a deep satisfaction at the rare compliment these young Americans were paying to Germany in playing to Germans in German. This might easily have backfired had the effort been misguided or half-hearted. That it was not is shown by the criticism of the drama critic of Cologne writing in Rundshau on July 25 midway through the tour: "This evening marked the final performance of the Theatre Institute (of Cologne University) for the current semester and proved the high spot of the season. Professor Schlossmacher's protests of indulgence for the fact that the cast was composed of students of German and not actors or drama students were unnecessary. Such modesty was without foundation. This was a real accomplishment, for these American students displayed real power and emotion in speaking the lines of the German text. Rather than single out any individual for praise it must be said that the finest element of the production was the ensemble playing. It was this that earned for the cast the storms of applause that followed the final curtain. May we hope for a return engagement after their performance at Erlangen."

The Erlangen engagement, unlike any of the other dates, was part of a drama festival. During the summer months the town of Erlangen invites college and university groups from all over Europe to bring a play and perform, each group in its own language. English, French, Italian and even Turkish colleges send productions. Thus an American troupe playing in German was so unusual that a rearrangement of the rules of the festival was necessary. As no American college had offered plays in English the festival proprietors decided to admit Durst as an American entry in a very special category. Here, too, the production was admired and cordially received.

The final performance of the first tour took place in the little Rhineland town of Eschweiler. The critic of the Aachener Zeitung summed up the objectives of the tour in wonderfully preceptive terms: "The play was a complete success! The visit of our American guests is culturally important not only for them but for us, too. We ourselves have only a vague notion of the American theatre as a whole. Our system of state and city subsidized theatres is unknown over there. It is rather the presentations in the colleges and universities in their profuse offerings of cultural plays that fills this place for them."

The evident success of the initial venture was repeated last summer. Leaving death and destruction at home, Germania produced three short comedies by Hans Sachs, the amiable shoemaker and Meistersinger of Reformation Germany. Again four students were cast, each one playing three different parts. As in the 16th century performances the women's parts were played by men, apparently to the delight of the native German audiences.

The first performance of this second troupe occurred in Marburg. All of the cast confessed to being "scared stiff" despite the many presentations of the plays in New England and Canada prior to the foreign tour. Yet the Marburg paper reported: "As the plays were arranged in performance they progressed in humor and complexity .. . and with them the cast rose to heights of subtlety and accomplishments." It was at Marburg too that the cast stayed at Germania House and delighted the German students with the knowledge that Dartmouth College also had a Germania.

Early in this tour the troupe met with an unusual situation. At Aachen because of negligent planning and almost no publicity the two scheduled performances were not given because of a lack of audiences. The date for the performance had been arranged for the identical date that Aachen was host to an International Horse Race.

At Giessen the cast was most cordially greeted by a U. S. Army colonel who was a graduate of Fordham. On hearing that the cast was from Dartmouth he asked them quite seriously if they were part Indian. At Frankfort by a mishap they were separated from their costumes and, in the traditional way, cast and costumes were reunited in the nick of time by the good graces of the U.S. Army. But these were merely incidental. Actually the tour went well and made as many friends as the first tour had. So much so that a member of the Dartmouth faculty, travelling quite independently in Germany, discovered that in many places where the troupe had been it was the distinct impression of the natives that Dartmouth College is the fount of German culture in the United States.

The choice of the folk comedies of Hans Sachs was well appreciated. One drama critic writing in the Saale Zeitung said: "It must be observed that these young men have done a worthwhile thing in selecting these precious comedies. They played with astonishingly excellent (German) diction and with a rare understanding of the underlying values of the three plays in the interpretation of the mental and physical attributes of the characters they represented."

At Wurtzburg the Frankisches Volksblat confessed itself delighted: "The young students speak German beautifully, slightly accented by their native tongue which, far from marring, seemed to add a charm to the Hans Sachs text."

The significant part of these tours lies in the fact that out of them may come the seeds of international understanding. This may be, and probably is, a minute contribution, yet where culture is concerned no effort is too small not to cause at least a ripple. Culture, as the Continental European understands it, has behind it ages of genius and greatness. The American, whose culture is scarcely 200 years old, seems to them young and immature. It was probably this that the critic of Bad Mergentheim had in mind when he wrote: "These students who make up the cast are not necessarily majoring in German. They may have taken German merely to fulfill a language requirement in the curriculum. Yet with what eagerness they throw themselves into this production, acting in what is, to them, a foreign tongue. This tour has an added and very important value in the fact that the students have an opportunity to see at first hand the country and people whose language they study. This may be one of the most positive advantages of the venture."

Positive indeed! But it might be well to point out that the critic had an opportunity to see at first hand four young Americans... and he evidently liked what he saw.

The four students at left, shown in Erlangen,made up last summer's Germania troupe. Leftto right: Morgan McGuire '55, Hamden,Conn.; Ronald Hengen '55, Richmond Hill,N. Y.; Peter Terplan '55, Buffalo, N. Y.; andTomm Shockey '56, Larchmont, N. Y.

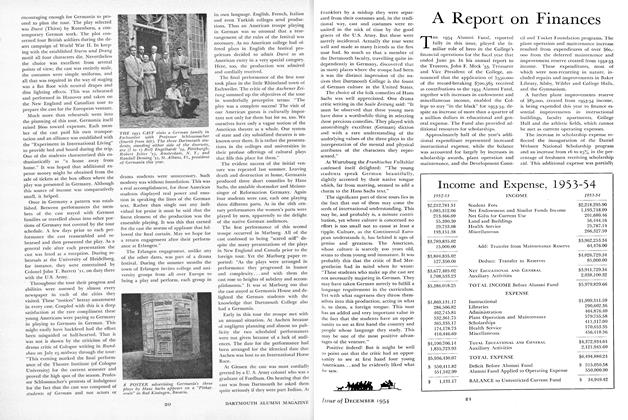

THE 1953 CAST visits a German family inEschweiler with Professor Schlossmacher(fourth from left). The three Dartmouth students, standing either side of the doorway,are (l to r) Rolf Engelhardt '54, Pittsburgh;Robert Jetter '53, Amsterdam, N. Y.; andRandall Deming '55, St. Albans, Vt., presidentof Germania this year.

A POSTER advertising Germania's threeplays by Hans Sachs appears on a "Plakatsoule" in Bad Kissingen, Bavaria.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePREFACE TO DARTMOUTH

December 1954 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

Feature"The Record of Their Fame"

December 1954 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

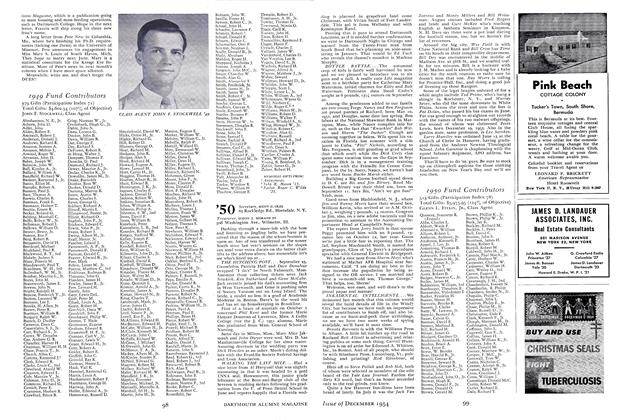

FeatureA Report on Finances

December 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

December 1954 By ALEX J. MCFARLAND, CHARLES V. RAYMOND, HENRY S. EMBREE, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1954 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDr. Myron Tribus of UCLA Named Dean of Thayer School

February 1961 -

Feature

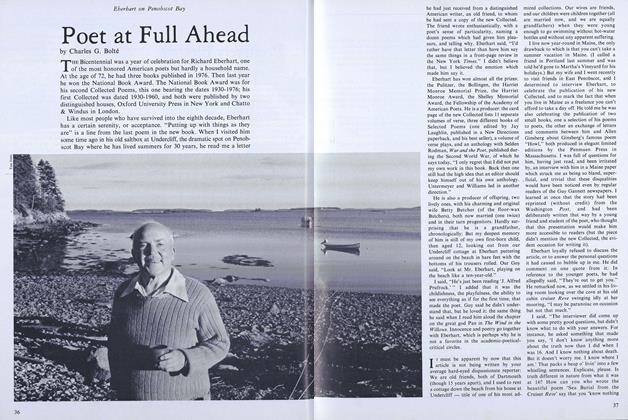

FeaturePoet at Full Ahead

September 1978 By Charles G. Bolte -

Feature

FeatureThe 1956 Commencement

July 1956 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1963

JULY 1963 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

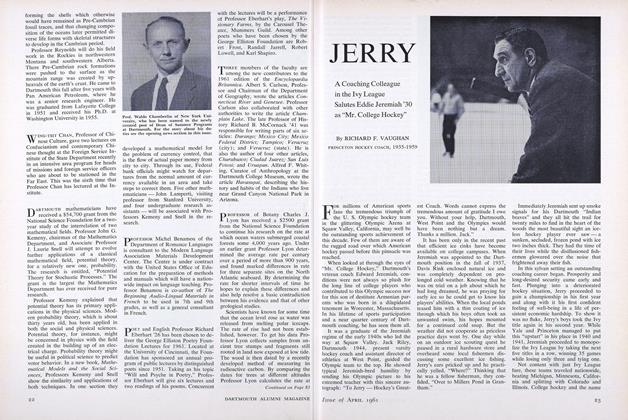

FeatureJERRY

April 1961 By RICHARD F. VAUGHAN -

Feature

FeatureFairly Faced

November 1975 By WILLIAM W. COOK