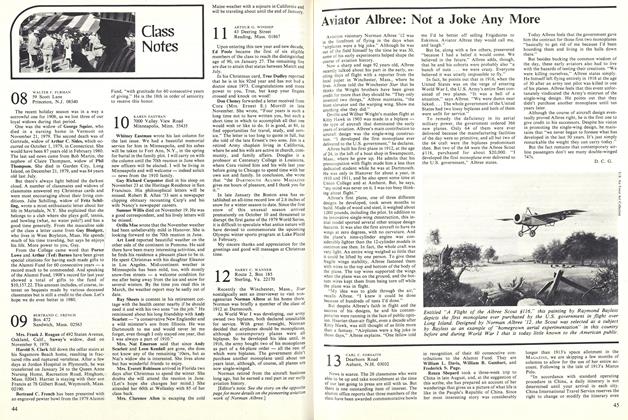

Aviation visionary Norman Albree '12 was in the forefront of flying in the days when "airplanes were a big joke." Although he was out of the field himself by the time he was 30, some of his early experiments helped shape the course of aviation history.

Now a sharp and sage 92 years old, Albree recently talked about his part in the early, exciting days of flight with a reporter from the local paper in Winchester, Mass., where he lives. Albree told the Winchester Star that he thinks the Wright brothers have been given credit for more than they should be. "They only invented two things," Albree maintains, "the front elevator and the warping wing. Show me anything else they did."

Orville and Wilbur Wright's maiden flight at Kitty Hawk in 1903 was made in a biplane the type of aircraft that dominated the early years of aviation. Albree's main contribution to aircraft design was the single-wing construction. "I developed the first monoplane ever delivered to the U.S. government," he declares.

Albree built his first plane in 1912, at the age of 24, in the loft of a boat shop in Swampscott, Mass., where he grew up. He admits that his preoccupation with flight made him a less than dedicated student while he was at Dartmouth. He was only in Hanover for about a year, in 1910 and 1911, and he also spent some time at Union College and at Amherst. But, he says, "my mind was never on it. I was too busy thinking about flight."

Albree's first plane, one of three different designs he developed, took seven months to build. Made of wood and steel, it weighed about 1,000 pounds, including the pilot. In addition to its innovative single-wing construction, this initial model sported several other unique design features. It was also the first aircraft to have its wings at zero degrees, with no curvature. And the plane's nine-cylinder engine was considerably lighter than the 12-cylinder models in common use then. In fact, the whole craft was very light. An entire wing weighed so little that it could be lifted by one person. To give these fragile wings stability, Albree fastened them with wires to the top and bottom of the body of the plane. The top wires supported the wings when the plane was on the ground, and the bottom wires kept them from being torn off while the plane was in flight.

"My idea was to glide through the air," recalls Albree. "I knew it could be done because of hundreds of tests I'd done."

But despite Albree's faith in flight and the success of his designs, he and his contemporaries were running in the face of public opinion. Heavier-than-air flight, even a decade after Kitty Hawk, was still thought of as little more than a fantasy. "Airplanes were a big joke in those days," Albree explains. "One fellow told me I'd be better off selling Frigidaires to Eskimos. Aviator Albree they would call me, and laugh."

But he, along with a few others, presevered "because I had a belief it would come. We believed in the future." Albree adds, though, that he and his cohorts were probably also "a bunch of nuts ... we were crazy. Everyone believed it was utterly impossible to fly."

In fact, he points out that in 1916, when the United States was on the verge of entering World War I, the U.S. Army's entire fleet consisted of two planes. "It was a hell of a situation," says Albree. "We were damn near licked. . . . The whole government of the United States had two lousy biplanes and both of them were unfit for service."

To remedy the deficiency in its aerial military power, the government ordered 366 new planes. Only 64 of them were ever delivered because the manufacturing facilities of the day were so primitive, and all but two of the 64 craft were the biplanes predominant then. But two of the 64 were the Albree Scout #ll6, purchased for about $20,000. "I developed the first monoplane ever delivered to the U.S. government," Albree states.

Today Albree feels that the government gave him the contract for those first two monoplanes "basically to get rid of me because I'd been hounding them and living in the halls down there."

But besides bucking the common wisdom of the day, these early aviators also had to live with the hazards of testing their creations. "We were killing ourselves," Albree states simply. He himself left flying entirely in 1918 at the age of 30 after an army test pilot was killed in one of his planes. Albree feels that this event unfortunately vindicated the Army's mistrust of the single-wing design. He points out that they didn't purchase another monoplane until ten years later.

Although the course of aircraft design eventually proved Albree right, he is the first one to give credit to his successors. Despite his vision in promoting the single-wing design, he maintains that "we never began to foresee what has developed in the last 50 years. It's just simply remarkable the weight they can carry today."

But the fact remains that contemporary airline passengers don't see many double-winged 7475.

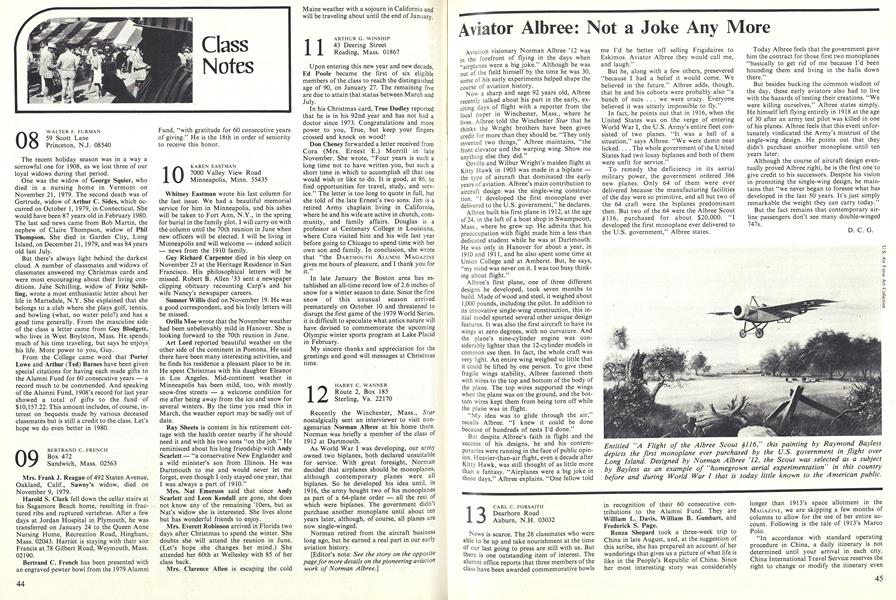

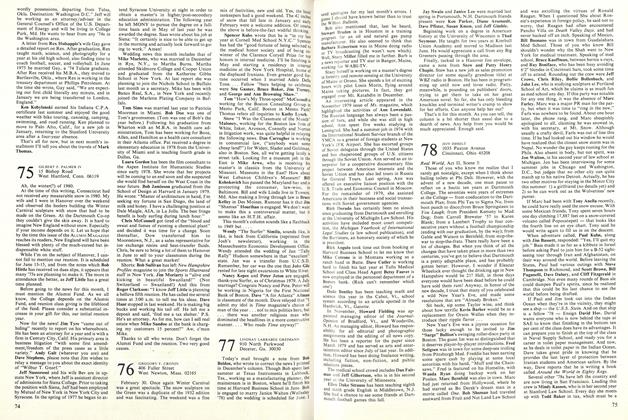

Entitled "A Flight of the Albree Scout #116," this painting by Raymond Baylessdepicts the first monoplane ever purchased by the U.S. government in flight overLong Island. Designed by Norman Albree '12, the Scout was selected as a subjectby Bayless as an example of "homegrown aerial experimentation" in this countrybefore and during World War I that is today little known to the American public.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

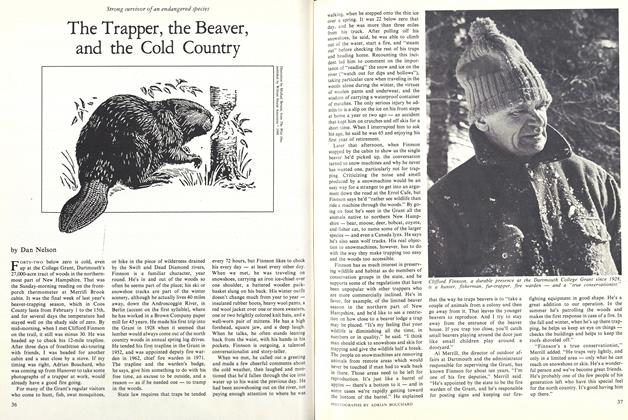

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

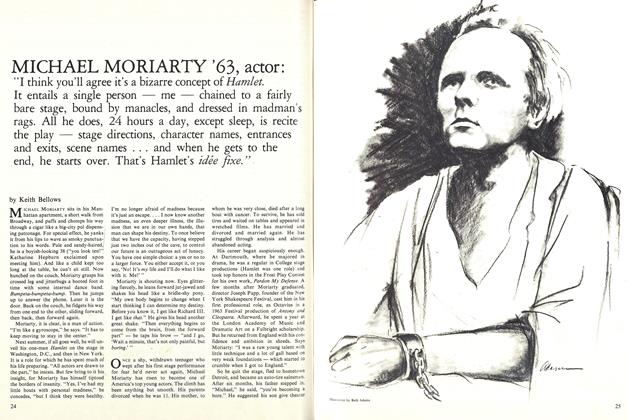

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

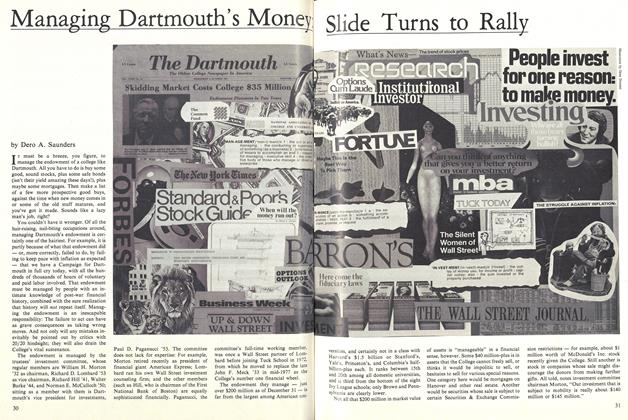

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Article

-

Article

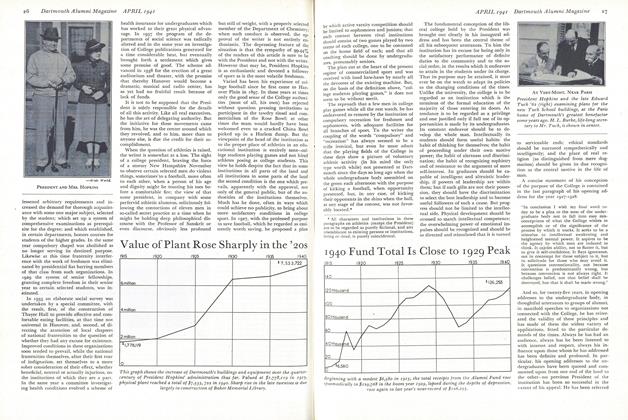

ArticleValue of Plant Rose Sharply in the '20s

April 1941 -

Article

ArticleGifts

September 1979 -

Article

ArticleHave Your People Blitz My People

November 1994 -

Article

ArticleFace to Watch

Sept/Oct 2002 -

Article

ArticleA Stranger in the House

MAY 1985 By Margaret Robinson -

Article

ArticleTurning the Tables

Sept/Oct 2003 By Susan DuBois '05