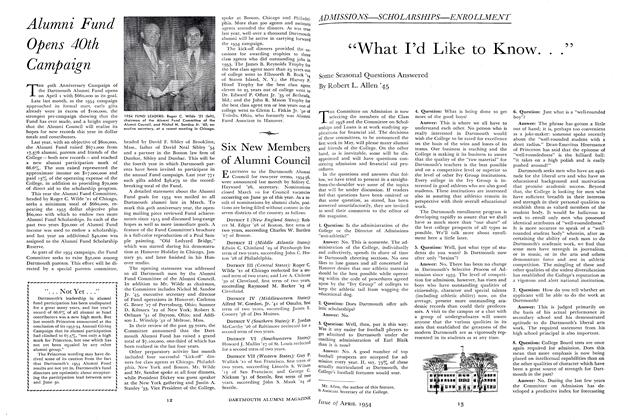

MAIN Street," says Sinclair Lewis in a foreword, "is the climax of civilization," and this may well be true in many locales where barter or display are of paramount importance. Filth or Michigan Avenues or the Red Square muster a brave and glistening front without hint of what may lurk in the background - the Avenue of the Americas, Clark Street, or the quaint "old-style" dwellings of Moscow. Hanover differs in one respect (if not indeed in others) from New York or Chicago or Moscow, in that the climax of its civilization is to be found in the library, the dormitories, the classrooms, or on the ski slopes, while Main Street is a mere utilitarian adjunct of minor operations.

For the freshman, newly arriving by auto, bus, helicopter or Irish Mail, Main Street is the first, and perhaps less than completely captivating, view of Hanover. It furnishes a prospect, without vista, of what one critic has denominated "bad brick bond and poor fenestration." On his right, the newcomer (who except in the rarest instances is trekking from the south) sees the over-rusticity of Tanzi's fruit store succeeded by a dismal series of

"fronts" trimmed with black or marbled glass - simple, honest worth masquerading as Tremont Street. On his left he is confronted with the New Look of the early 'thirties, when all the street level trim was painted white, so that the stores, cowering under a couple of superior stories of early schoolhouse brick, give the impression of a series of red-headed albinos. Only the College-constructed Lang Building, nestling behind the Inn, gives any smidgen of charm or distinction to the downtown district of the village.

Once across Wheelock Street our freshman is swallowed up by the College, to reappear shortly minus suitcase and jacket, and with wonder in his heart as, jostled by confident upper-classmen and plodding townsfolk, he prospects for furniture, thumb tacks, stationery and comic books. Main Street is not the climax but it is a lively slice of local civilization, and from the Coffee Shop window, as from the terrasse of Shepheard's in Cairo, one can sooner or later catch a glimpse of everybody in the world. In term time it is thronged with students to the practical effacement of the citizenry, whose innings come before 11 a.m. or during vacations. But they are an orderly throng and although no walls define the College from the town, student riots never occur on the Street as they do in Harvard Square, Chapel Street, the purlieus of Penn, or at other institutions where Lebensraum is at a premium. Our crowds are bent on their lawful occasions in search of such necessities of life as newspapers, mail, popsicles, or the movies. Not that the offerings are limited - print shops, pipe shops, clothing shops, music shops abound, interspersed with establishments catering to the more prosaic demands of the householder. A quest for black flannel pajamas (for the celebration of an arctic Witches Sabbath) or for replacements for pieces lost from a set of dominoes may as likely be satisfied on Main Street as in some more pretentious agorae. It is all things to all men, though the women come off second best.

Rumors are rife of imminent changes in the ownership of stores, calling to mind the mutations of the passing years. An era ended when Scotty's and Phil's closed their doors and their jars of peanut butter and left the feeding of the multitude to swanker - Such names as Rich's, Guyer's, Dudley's, Downing's, and Leavitt's have long disappeared from currency. Only two selfservice groceries survive the former numerous peripatetic food shops. The bank, the post office, the fire station, and the Press have all taken new stances since our earliest time, and only Tanzi's and Rand's have endured without change in name or décor.

As for the upper chambers, they are a mysterious warren of apartments, hairdressers, dental surgeons, and photographers; and few students, we'll venture, know their way about these labyrinthine retreats. Suffice it that the ground level shops cater adequately to common needs, and if here one cannot readily find a nut for an English threaded bicycle bolt, neither can he unearth it within a reasonable distance of the Grand Central Zone. Main Street is not a breath-taking production at first or even second blush, but it is a comfortably familiar scene, an untrammeled heath, a stretch of territory that, like Vice, we first endure, then pity, then embrace.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Introvert at Dartmouth

April 1954 -

Feature

FeatureADMISSIONS—SCHOLARSHIPS—ENROLLMENT

April 1954 By Robert L. Allen '45 -

Article

ArticleThaddeus Stevens, 1814

April 1954 By JOHN S. MONAGAN '33 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

April 1954 By REGINALD B. MINER, WILLIAM H. PERRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

April 1954 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, MARVIN L. FREDERICK

BILL McCARTER '19

-

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago .... Cry Havoc!

December 1933 By Bill McCarter '19 -

Article

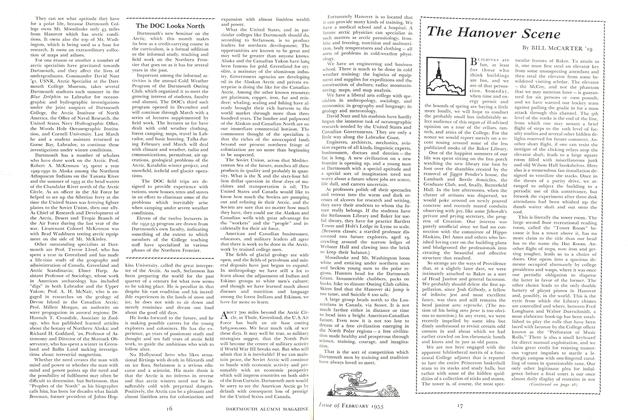

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

February 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

July 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

October 1953 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

November 1954 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

May 1956 By BILL McCARTER '19

Article

-

Article

Article"I am glad that the sons of Dartmouth

-

Article

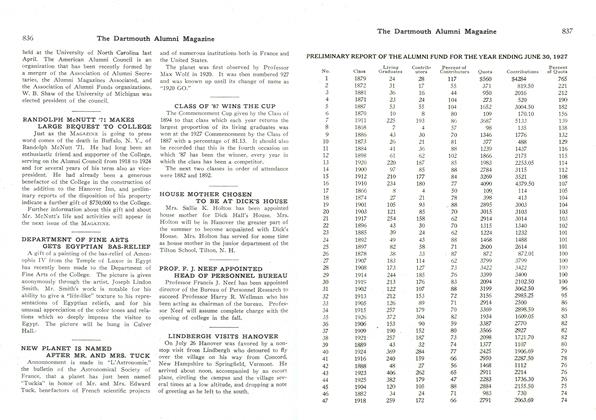

ArticleLINDBERGH VISITS HANOVER

AUGUST, 1927 -

Article

ArticleCongratulations

November 1935 -

Article

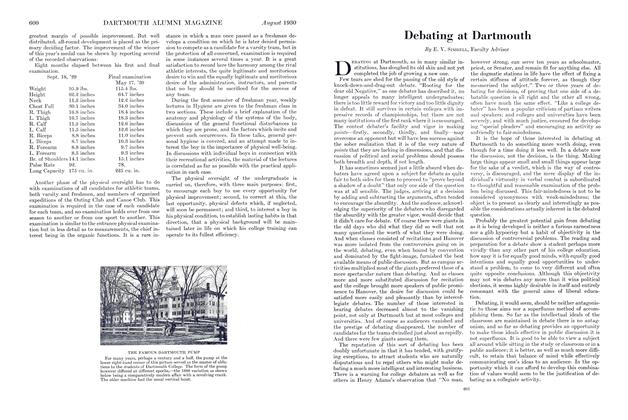

ArticleDebating at Dartmouth

AUGUST 1930 By E. V. Simrell, Faculty Advisor -

Article

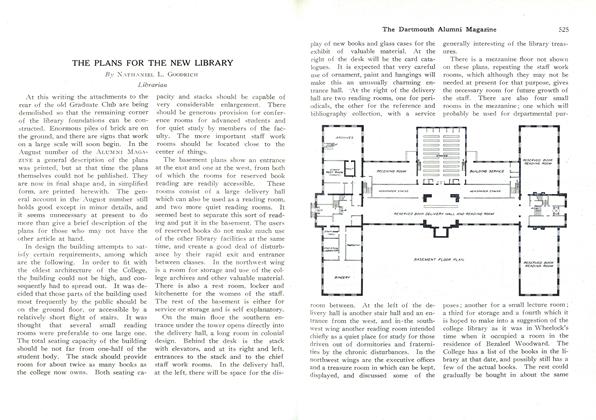

ArticleTHE PLANS FOR THE NEW LIBRARY

APRIL, 1927 By Nathaniel L. Goodrich -

Article

ArticleThayer School

DECEMBER 1966 By S. RUSSELL STEARNS '38