The following brief address was delivered by Mr. Zimmerman, on behalf of thealumni, at the 100th annual meeting of theGeneral Alumni Association, June 19.

ALUMNI TRUSTEE

THE honor of speaking for and to a distinguished group of the alumni family on the occasion of the 100th annual meeting of the General Association of Alumni is in itself a signal one. It is further enhanced by being so graciously introduced by a fellow alumnus. And when, as happens here, that fellow alumnus, Horace Taylor, is also a good friend and classmate of the vintage of '23, then my cup of pleasure is indeed filled to overflowing. I shall attempt not to let the brew become too heady, however, but rather retain a sense of humility sufficient to qualify me even for an Arthur Godfrey program.

I hasten to add that if I succeed in retaining a proper sense of perspective, a major share of credit must go to Sid Hayward who in briefing me for my appearance here admonished that I "make it short, make it informal, and make it my own." "Don't try," added he, "to cover everything from Confucius to Communism."

I shall confine my remarks to that period between the events of the early twenties and the attempted prohibition of liquor and the events of the present and the attempted prohibition of thought.

These three decades witnessed many changes in the world and in Dartmouth. Yet there remains much in the world and in Dartmouth which is unchanged. This is graphically illustrated by a quick review of the headlines of the first half of 1923. "New York talks to England by phone; heard by Marconi." "Last unit of U.S. Army of Occupation sails for home from Antwerp." "Couè says he heals love's heartaches." "Lenin and Trotsky both incurably ill." "Pola Negri breaks engagement to Chaplin: Both agree he is 'too poor' to marry her." "Soviet recognition refused by Hughes." "Senator Hiram Johnson warns U.S. to stay out of World Court." "U.S. Army plane makes record 2700-mile nonstop dash across continent in 27 hours." "Yanks score three in tenth and win." "Harding declares that no President can be for Isolation." "Peking accepts terms to free captives." "Sinclair refuses records to Senate - Subpoena is issued." "Dartmouth beats Harvard 17 to 15 to win its fifth straight game."

Most of 1923's headlines would look perfectly natural in this morning's issue of your daily paper merely by transposing names and dates. Indeed, most of the problems which confront the world today have their roots deeply imbedded in the past. Even a casual glance backward, such as we have taken, drives home the fact that the seeds of today's problems had already been planted and taken root when my class gathered in the Bema in June of 1933.

The United States, victorious in World War I, was neither prepared nor willing to occupy the position of world leadership in which events had inevitably placed it. By withdrawing from international leadership, we permitted the selfish forces of nationalism to become revitalized. By refusing to give leadership to the forces of freedom, we invited anti-democratic forces to grow influential.

Our world of 1923 most certainly was a more cheerful one in which to graduate than is that of today. While accepting our share of responsibility for this retrogression, we must nevertheless reject any thought of fear or despair. Instead, we must embrace courage and hope, based on faith - faith that a well educated America need not fear for the future of this country and of this world. There is no iron curtain which cannot be penetrated by truth, no darkness which cannot be dispelled by light, no hate, greed, and distrust which cannot be destroyed by love, charity, and belief provided we continue to educate all those who have the potential capacity to use such knowledge with intelligence, humility, and dedication. Such education is primarily the business of the liberal arts colleges such as Dartmouth.

I could not help but think of this, and to take courage, when I had the truly thrilling experience last Sunday of participating in the Commencement and Baccalaureate exercises in this, Dartmouth's 185th year. The Valedictory to the College by Milton Kramer, the Valedictory to the seniors by President Dickey, the conferring of honorary degrees with their beautifully conceived citations, the Commencement Address by Roy Larsen, all of these were in the finest tradition of Dartmouth. But most inspiring of all was the opportunity of looking into the faces of somewhat over 550 men receiving the Bachelor's degree. "These men," intoned President Dickey, just as had Presidents Hopkins and Tucker and their predecessors in office, "have completed all the requirements for the Bachelor's degree of Dartmouth College and are worthy of the rights, honors, and obligations pertaining thereto."

On such an occasion, any alumnus need not feel abashed if there is a tautness in his, throat, a tug at his heart, a tear in his eye. For in a different yet very real sense, this Commencement belongs to every alumnus, to '94, to '24, and to all the other classes — just as truly as it belongs to '54.

Perhaps herein lies the key to what is known as the Dartmouth spirit, namely, that the College has made us part of herself and we have made the College part of ourselves. We have simultaneously added strength to the Dartmouth spirit and gained strength from that spirit, and both we and the College have profited by the interflow. It is this feeling of belonging, the knowledge of participation which characterizes the Dartmouth spirit, for participation in itself is conducive to loyalty. One feeds upon the other!

Dartmouth means different things to each of us, but basic and common to all of us is the great emotional, intellectual, social, and educational experience which was ours at Dartmouth.

There are three basic institutions which influence a man throughout his entire life: Home and the influence of family; Church and the influence of religion; School and the influence of education. We have the one common bond and the one common influence which is Dartmouth.

That influence is expressed in the purpose of the liberal arts college, to teach men to live a more useful life and to prepare men to make a better living. Making a better living is important only to the extent that it enables us to live a more useful life. If we accept this as the purpose of a liberal arts education, then the effectiveness of a Dartmouth education will be measured by the men it turns out and how well they serve society.

Education itself is defined as "the process of leading out of." Out of what and into what? It seems to me that it is a leading out of ignorance, prejudice, and confusion into understanding, tolerance, and discernment.

To me, the Dartmouth educational experience was one which led into a new, great, broader, and clearer world. With separation from family and home came the development of self-reliance. With exposure to other men of varying social, economic, and geographic backgrounds came tolerance. With exposure to new ideas and a disturbance of old ideas leading to a reexamination of old beliefs and prejudices came inquisitiveness. It was an eventual realization that to be steadfast to Truth, we must not merely accept it but we must first understand it. It was a transition from a feeling of affection for mother and father to a sophomoric feeling of superiority and an eventual feeling of love, respect and humility. It was the realization that others were not only willing to accept and to treat me as a man, not a boy, but that they expected me to be one. From this came the further realization that I must accept the responsibilities of manhood.

In me, there grew an appreciation of the decency, the generosity, the inherent goodness of men as represented by the faculty and administration, the friends of the College, and the alumni - all of whom had made my Dartmouth experience possible. There was the realization that in order to get we must also give; that when we take away that which we get from others, there is very little left. There was the realization that happiness is not complete until it is shared.

To me, there was finally the realization that the Dartmouth experience was a privilege, not a right, and inherent in that privilege was opportunity, responsibility and obligation.

Foremost among these responsibilities of the alumni is to safeguard tenaciously the basic obligation of Dartmouth to continue to inspire men to seek and speak the truth as they see it. Only in this way can the College justify itself to society by the men it turns out. Only in this way can Dartmouth men justify the College and themselves to society by turning out to be the type of men which Dartmouth gave them every opportunity of being.

My summary will be that of the Southern preacher. Said he, "Dere's an election going on all de time. De Lawd votes fo you. De Debil votes agin you. And you casts de decidin' vote." May Dartmouth men always distinguish right from wrong, truth from falsehood, and have the courage to cast a decisive vote, which in the long run will also be the deciding vote.

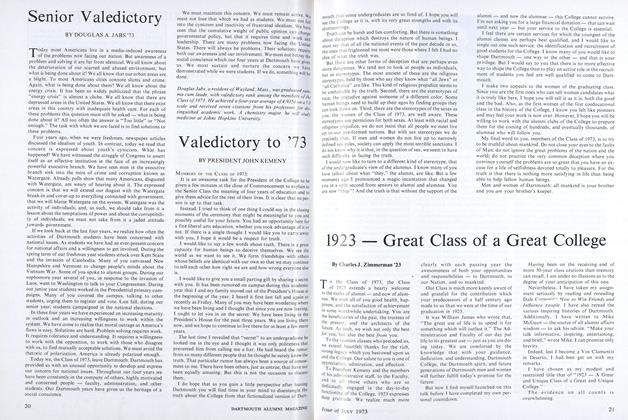

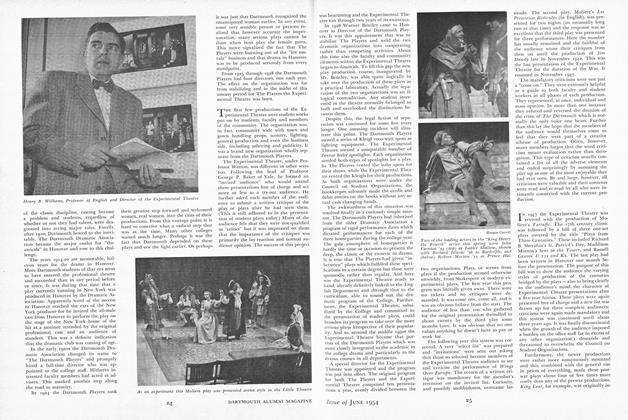

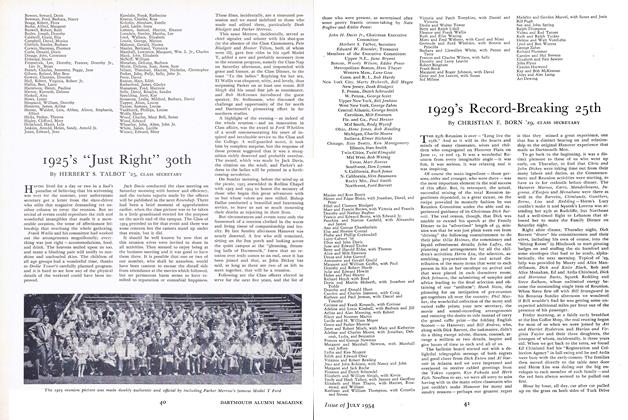

Charles J. Zimmerman '23 (right), who spoke for the reuning alumni, and Horace F.Taylor '23, presiding, officer, shown at the Alumni Association meeting June 19.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePresident Emeritus Hopkins Is Honored With Dartmouth's First Alumni Award

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureRobert S. Oelman '31 Heads Alumni Council for 1954-55

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureE. S. French Retires as Life Trustee; Ruml Succeeds Him

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureAnother Record for the Fund

July 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929's Record-Breaking 25th

July 1954 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN '29, BILL ANDRES, SQUEEK. -

Article

ArticleThe 1954 Commencement

July 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON

CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN '23

Article

-

Article

ArticleSYRACUSE UNIVERSITY OFFERS FELLOWSHIP

March, 1924 -

Article

ArticleRationing Hits Here

March 1943 -

Article

ArticlePoison Information Center

February 1958 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

November 1973 -

Article

ArticleThe Indian Symbol: a vote not to "encourage" it

July 1974 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1937 By HERBERT F. WEST '22