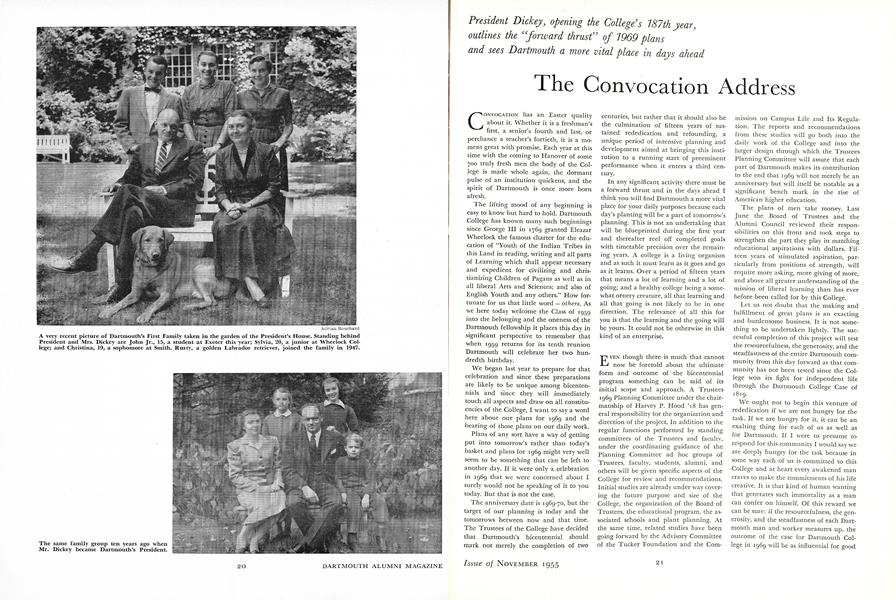

President Dickey, opening the College's 187th year,outlines the "forward thrust" of 1969 plansand sees Dartmouth a more vital place in days ahead

CONVOCATION has an Easter quality about it. Whether it is a freshman's first, a senior's fourth and last, or perchance a teacher's fortieth, it is a moment great with promise. Each year at this time with the coming to Hanover of some 700 truly fresh men the body of the College is made whole again, the dormant pulse of an institution quickens, and the spirit of Dartmouth is once more born afresh.

The lifting mood of any beginning is easy to know but hard to hold. Dartmouth College has known many such beginnings since George III in 1769 granted Eleazar Wheelock the famous charter for the education of "Youth of the Indian Tribes in this Land in reading, writing and all parts of Learning which shall appear necessary and expedient for civilizing and christianizing Children of Pagans as well as in all liberal Arts and Sciences; and also of English Youth and any others." How fortunate for us that little word - others. As we here today welcome the Class of 1959 into the belonging and the oneness of the Dartmouth fellowship it places this day in significant perspective to remember that when 1959 returns for its tenth reunion Dartmouth will celebrate her two hundredth birthday.

We began last year to prepare for that celebration and since these preparations are likely to be unique among bicentennials and since they will immediately touch all aspects and draw on all constituencies of the College, I want to say a word here about our plans for 1969 and the bearing of those plans on our daily work.

Plans of any sort have a way of getting put into tomorrow's rather than today's basket and plans for 1969 might very well seem to be something that can be left to another day. If it were only a celebration in 1969 that we were concerned about I surely would not be speaking of it to you today. But that is not the case.

The anniversary date is 1969-70, but the target of our planning is today and the tomorrows between now and that time. The Trustees of the College have decided that Dartmouth's bicentennial should mark not merely the completion of two centuries, but rather that it should also be the culmination of fifteen years of sustained rededication and refounding, a unique period of intensive planning and development aimed at bringing this institution to a running start of preeminent performance when it enters a third century.

In any significant activity there must be a forward thrust and in the days ahead I think you will find Dartmouth a more vital place for your daily purposes because each day's planting will be a part of tomorrow's planning. This is not an undertaking that will be blueprinted during the first year and thereafter reel off completed goals with timetable precision over the remaining years. A college is a living organism and as such it must learn as it goes and go as it learns. Over a period of fifteen years that means a lot of learning and a lot of going; and a healthy college being a somewhat ornery creature, all that learning and all that going is not likely to be in one direction. The relevance of all this for you is that the learning and the going will be yours. It could not be otherwise in this kind of an enterprise.

EVEN though there is much that cannot now be foretold about the ultimate form and outcome of the bicentennial program something can be said of its initial scope and approach. A Trustees 1969 Planning Committee under the chairmanship of Harvey P. Hood '18 has general responsibility for the organization and direction of the project. In addition to the regular functions performed by standing committees of the Trustees and faculty, under the coordinating guidance of the Planning Committee ad hoc groups of Trustees, faculty, students, alumni, and others will be given specific aspects of the College for review and recommendations. Initial studies are already under way covering the future purpose and size of the College, the organization of the Board of Trustees, the educational program, the associated schools and plant planning. At the same time, related studies have been going forward by the Advisory Committee of the Tucker Foundation and the Commission on Campus Life and Its Regulation. The reports and recommendations from these studies will go both into the daily work of the College and into the larger design through which the Trustees Planning Committee will assure that each part of Dartmouth makes its contribution to the end that 1969 will not merely be an anniversary but will itself be notable as a significant bench mark in the rise of American higher education.

The plans of men take money. Last June the Board of Trustees and the Alumni Council reviewed their responsibilities on this front and took steps to strengthen the part they play in matching educational aspirations with dollars. Fifteen years of stimulated aspiration, particularly from positions of strength, will require more asking, more giving of more, and above all greater understanding of the mission of liberal learning than has ever before been called for by this College.

Let us not doubt that the making and fulfillment of great plans is an exacting and burdensome business. It is not something to be undertaken lightly. The successful completion of this project will test the resourcefulness, the generosity, and the steadfastness of the entire Dartmouth community from this day forward as that community has not been tested since the College won its fight for independent life through the Dartmouth College Case of 1819.

We ought not to begin this venture of rededication if we are not hungry for the task. If we are hungry for it, it can be an exalting thing for each of us as well as for Dartmouth. If I were to presume to respond for this community I would say we are deeply hungry for the task, because in some way each of us is committed to this College and at heart every awakened man craves to make the commitments of his life creative. It is that kind of human wanting that generates such immortality as a man can confer on himself. Of this reward we can be sure: if the resourcefulness, the generosity, and the steadfastness of each Dartmouth man and worker measures up, the outcome of the case for Dartmouth College in 1969 will be as influential for good on the years beyond as was the decision of Chief Justice Marshall's Court on the future we inherited from the resourcefulness, generosity and steadfastness of President Francis Brown and Daniel Webster, and those who stood with them in making the case for Dartmouth College one hundred and fifty years before.

It probably is well to say again that although our planning will take the long and large view, we also intend that it shall have the reality of being relevant to the daily needs and tasks for which we are answerable. Each year between now and 1969 will be a year of combined study, planning and action on progressively widening sectors across the entire front of Dartmouth life. This, gentlemen, is simply another way of saying that Dartmouth intends to keep the promise of her purposes to you as well as to tomorrow.

ALL this is manifestly important to you and to this College and yet the period to which we look may be of transcendent importance to all men. Institutions like the rest of us have to take their birthdays where they find them and for Dartmouth that is the year 1969-70, but we will be missing much in measuring our opportunity if we fail to sense that the particular fifteen years between now and then may be propitious beyond the emphasis of any saying for the kind of effort we propose.

I think it is entirely possible that between now and1 Dartmouth's bicentennial year the issue of war or peace will make or break our brand of education. I say this because I believe that the criteria we inherited for judging the quality of a man's liberation will at best be badly twisted in any society that fifteen years hence is still holding its breath as it leaps from summit to summit.

My generation fancies it to be relatively easy to resist, or temper, or tolerate without embracing, the evils and excesses that go with the progressively poisoned climate of a cold war, but let a generation follow that has known no other climate, and today's enticements for adopting the methods of our enemies may be so far accepted that it will be a short step to the next question - "Why not their ends as well?" Even if it is never quite that simple, a society moving in that direction will be a society moving away from the values and ways of liberated men. It will be a literally forbidding climate for liberal learning.

The peril of a thirty years cold war is real enough, but in facing that peril there is no good in blinking the fact that up to now the only self-respecting alternative permitted to us has been war without even the cold comfort of a qualifying adjective.

We are now just ten years beyond World War II. There is no need to tell any veteran of Korea that these have been mean, dangerous, death-ridden years; and at home our travail with the ancient evil of irresponsible accusation in the streets and market places has added a harsh condemnatory word to the language. It has been a decade of aftermath well matched to the bitter harvest of the 1935-45 decade. But despite all its harshness and the nearmisses of disaster, it is worth remembering that the rough passage of this past decade has been presided over by statesmen and soldiers who, having borne the duties of World War II, inherited the hellish assignment of being midwives at the birth of weapons whose unreckoned power was heretofore reserved to Earth's Creator. I think we can thank those unlucky stars of our leaders for the fortunate fact that this first apprehensive decade of nuclear power was punctuated at decisive moments by both the bold action and the courageous restraint of statesmanship. I beg of you never to forget to ask of your time, can as much be expected of men for whom World War II and the revolutionary aspect of nuclear power will rapidly become remote, impersonal incidents of history?

Leaving aside the "spirit of Geneva" until it is proven to have roots and a future of growth, I think the possibility has become substantial within the past five years that our civilization may be on the threshold of a decisive "breakthrough" on the peace front. Judgment in these matters cannot be much better than a hunch, but the evidence seems to me to be building up in favor of the view that if we can use the next fifteen years creatively to exploit and extend today's uneasy recognition that war between the great powers is certain suicide, our time can turn the corner away from World War III. The ways of moral and political growth being what they are, this particular turn will be more of a curve than an angle, but, if God be willing, the great work of the next fifteen years can be the building of the moral roadbed and the laying of the international tracks of political structure on which a right of way of human hope can be established. On the other hand, if out of ignorance, timidity, or laziness we squander the opportunity of these years, I should think that the King of the Wild Frontier would do well to trade in his coonskin hat for a serviceable space suit and travel.

GENTLEMEN, I have spoken of large things: a fifteen year commitment to the rededication of a historic college of the liberal arts and on the larger scene the prospect that these may be the golden years for getting forward decisively with the prime public business of our time - the organization of international law and order. Such great matters properly concern you and me personally because in one way or another they fix the terms of life for each of us. Many years ago that truth was caught in John Donne's clean line: "No man is an island, entire of itself." But as we stand here on the threshold of working together at the task of your education I should like to press the claim of another truth - every man is a frontier unto himself.

This, I think, is the central truth around which all education pivots. Certain it is that whenever a man ceases to be a frontier unto himself the education of that man is at an end. And yet here is a frontier that never vanishes so long as it is being pushed back by a man himself. It vanishes only when a man settles down, is content with himself, and knows no further hunger.

It is my impression that the greatest challenge the colleges face is that of inducing hunger in those students who through no fault of their own are simply not very hungry. I need hardly say I am not here addressing myself to dining hall problems. It does no harm, however, to remind ourselves that even at the level of physical hunger there is rarely an American boy among us who has known what it is to go to bed hungry or to wake up in the morning not knowing when and whether he will eat that day. No humane person would want it to be otherwise, but neither is there any point to protecting you from the fact that no one has ever invented a substitute for wanting to eat as a prod for men as well as for mice.

Hunger is not a tame thing. In many forms it dwells on or even beyond the borders of civilized life. It is often downright unpleasant and even dangerous to have around in a civilized community. Aggression, ruthless pursuit of any end, cancerous materialism in the human soul, all these are malign manifestations of wanting something very much. But whether the ill be in what is wanted or how it is sought, the cure is surely not in removing from human experience a healthy sense of hunger. Indeed these are the very ills liberal learning can treat, but as with everything else that matters the getting of liberal learning takes a lot of wanting and a lot of work.

And, as the Irishman says, "What might you be wanting?" This is a larger and more personal question than can be answered by one man for another. But perhaps we can begin by wanting what is here for the getting by everyone. First and everlastingly should be a hunger for learning to think and for learning to love the pursuit of truth. These are the sinews of competence. Secondly, if you are to want what is here, covet those liberating qualities that have brought beauty, meaning and grace to human experience. These are the guardians of conscience.

These things, gentlemen, are acquired tastes. As such they take a lot of learning and, at least until you have acquired a stroke and style of your own, learning is work, whether the game be tennis, football, or physics. Thereafter it begins to be fun and at that point the wanting that goes, with hunger takes pretty good care of itself - does it not? Until that time how do you begin to be hungry for the work of the day, particularly if you are a contemporary American who probably up to now has had little or no exposure to the deep truth in that line from Voltaire's Candide: "Work keeps at bay three great evils, boredom, vice, and need." If you are one of the lucky few whom life has already taught something about hunger and work, you and Dartmouth are probably already well met.

There is no magic for moving a full man with an empty mind, but I can tell you that just as many a politician has been saved at election time by "running scared," quite a few fellows have won out over their lush, lazy lot by making believe they were hungry until, lo and behold, they found they had worked up a real appetite. One of the most wonderful instances of this kind of make-believe is , found in the Rogers and Hammerstein musical play, The King and I, in which, as you may remember, Gertrude Lawrence sang these words about being brave right up to the night, as it happened, that mortal illness rang down her final curtain:

"Whenever I feel afraid I hold my head erect And whistle a happy tune, So no one will suspect I'm afraid.

"The result of this deception Is very strange to tell, For when I fool the people I fear I fool myself as well!

' Make believe you're brave And the trick will take you far; You may be as brave As you make believe you are."

Gentlemen, what would you think of making believe for the next nine months that you re not afraid to pretend you're hungry for the best of all that is Dartmouth?

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such.

Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be.

Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you.

We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

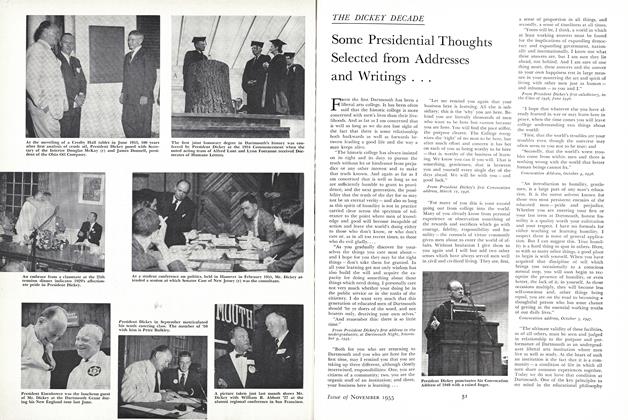

FeatureSome Presidential Thoughts Selected from Addresses and Writings ...

November 1955 -

Feature

FeatureTHE REASONS Behind Corporate Gifts to Dartmouth

November 1955 -

Feature

FeatureA Review of Major College Events

November 1955 -

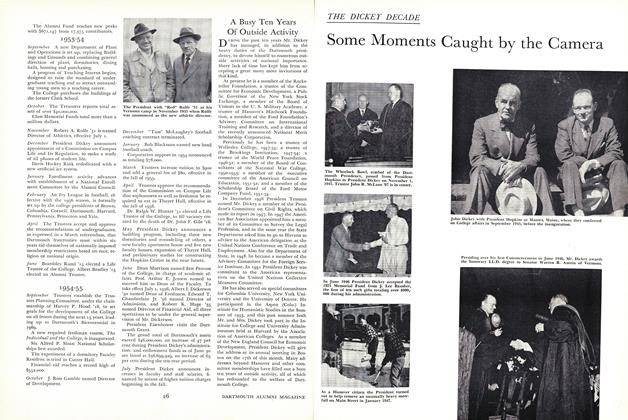

Feature

FeatureSome Moments Caught by the Camera

November 1955 -

Article

ArticleFootball

November 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE

Features

-

Feature

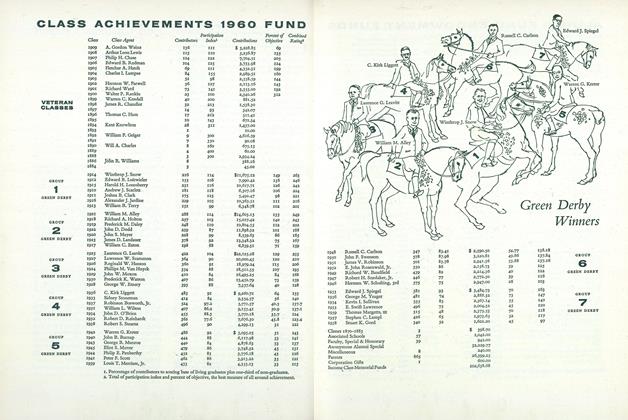

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVEMENTS 1960 FUND

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureIt Was A Dartmouth Jinx All the Time

November 1960 By AMOS N. BLANDIN '18 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2013 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureHow Does It Feel?

Jan/Feb 2010 By LEANNE MIRANDILLA ’10 -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

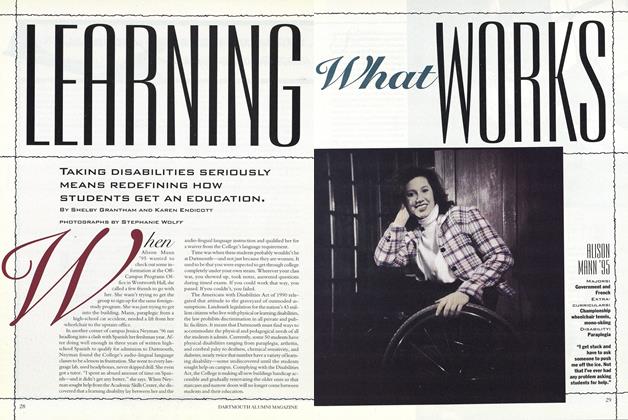

FeatureLEARNING WHAT WORKS

May 1995 By Shelby Grantham and Karen Endicott