By PorterG. Perrin '17. Chicago: Scott Foresman,1955. 528 pp. $2.50.

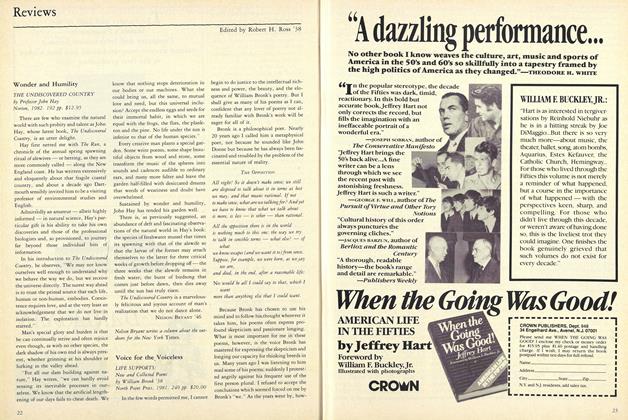

As I read through this book I found myself asking, "Surely not another?" It was: the same principles, the same precepts that Barrett Wendell had set down in English Composition in 1891; another- improvement on Wendell with the customary claim of producing something new and therefore superior.

The introduction says: "They [high school students] soon learn that the book gives them advice based on accurate observation of language - advice that will really work. That they feel added respect for their English course is a natural result." The authors know that high schools pour out students who have not been adequately trained in English composition, and they would have us believe that the fault is in inadequate textbooks on the subject, a fault that their book will correct. They know as well as I, however, that their advice will not "really work," any more than Wendell's or that of any of the numerous books on composition that have appeared since 1891.

Unquestionably the book is pretty. The printing is good, the lazy student is tempted with many illustrations of a kind favored in modern children's, books, and so little strain is placed on the reader's powers of concentration by such devices as the printing of quotations in ink colored differently from that of the main text that the book may be called a triumph of the bookmaker's art. But the contents and the order of their presentation are little changed from those of the nineties, for the simple reason that the principles of good writing remain the same. What is offered is a 1955 model with a snappy new paint job, power steering, and the same old engine.

This is not the end of my quarrel with the authors. They plume themselves on their "realistic approach" to composition, realism which makes itself depressingly felt in the constant use of journalistic illustrations. The book assumes that high school students have never, nor will ever, read anything except newspapers, magazines, and best-sellers. This is realistic, I concede, but is it the teacher's function to sacrifice everything to realism? Has he been freed from all responsibility for the minds of those whom he teaches?

The book has much to recommend it, however. Chapter 8, "Using The Dictionary," and the next four chapters, on sentence construction, are excellent. The Index, a kind of glossary of usage, is perhaps the best thing in the book. My criticism is that the authors claim and attempt too much. The sound heart of the book, plus the Index, would make an unpretentious, useful volume that any high school teacher of composition might welcome.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureADMINISTRATIVE CHANGES

July 1955 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Fund Tops $760,000

July 1955 -

Feature

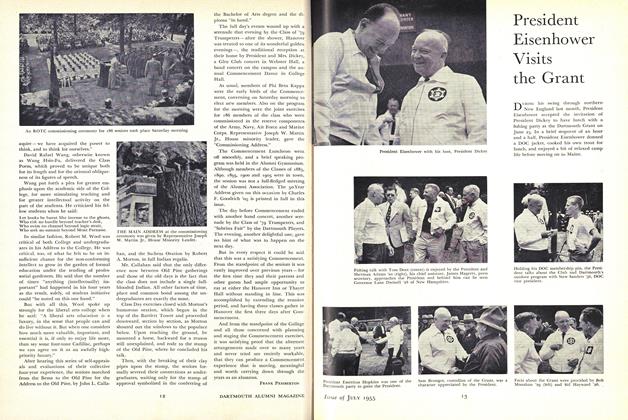

FeaturePresident Eisenhower Visits the Grant

July 1955 -

Class Notes

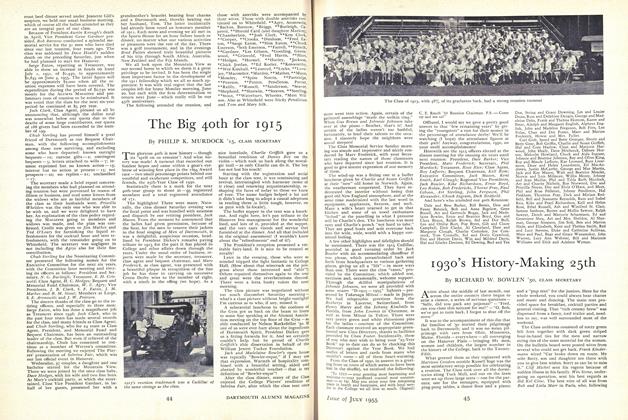

Class Notes1930's History-Making 25th

July 1955 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN '30 -

Article

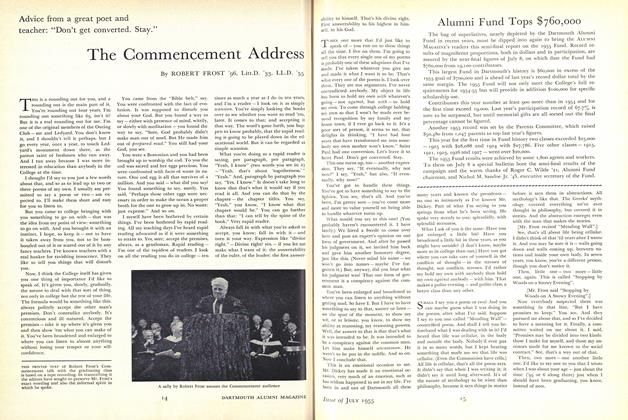

ArticleThe 1955 Commencement

July 1955 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Class Notes

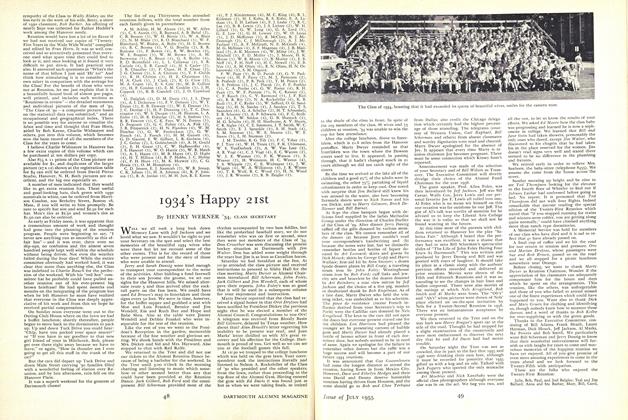

Class Notes1934's Happy 21 st

July 1955 By HENRY WERNER '34

HARRY T. SCHULTZ '37

Books

-

Books

BooksTROUT FISHING

June 1950 By Albert H. Hastorf -

Books

BooksPIT BULL.

FEBRUARY 1968 By BROWNLEE McKEE -

Books

BooksPutting Your Best Food Forward

OCTOBER, 1908 By Carole Ann Stashwick, M.D. -

Books

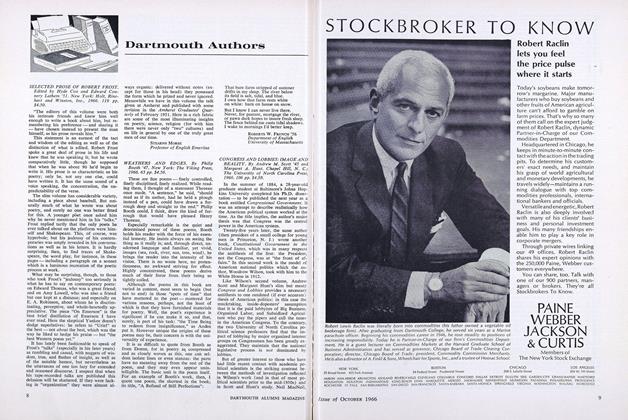

BooksCONGRESS AND LOBBIES: IMAGE AND REALITY.

OCTOBER 1966 By DAVID M. KOVENOCK -

Books

BooksROBERT FROST POETRY AND PROSE.

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksGREAT PRAISES.

November 1957 By THOMAS H. VANCE