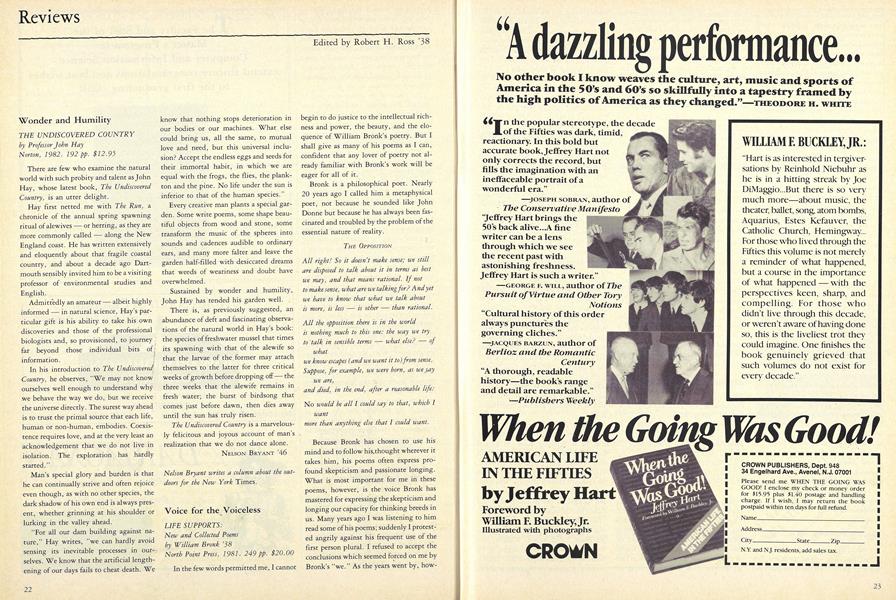

LIFE SUPPORTS: New and Collected Poems by William, Bronk '38 North Point Press, 1981. 249 pp. $20.00

In the few words permitted me, I cannot begin to do justice to the intellectual richness and power, the beauty, and the eloquence of William Bronk's poetry. But I shall give as many of his poems as I can, confident that any lover of poetry not already familiar with Bronk's work will be eager for all of it.

Bronk is a philosophical poet. Nearly 20 years ago I called him a metaphysical poet, not because he sounded like John Donne but because he has always been fascinated and troubled by the problem of the essential nature of reality.

THE OPPOSITION

All right! So it doesn't make sense; we stillare disposed to talk about it in terms as bestwe may, and that means rational. If notto make sense, what are we talking for? And yetwe have to know that what we talk aboutis more, is less is other than rational.

All the opposition there is in the worldis nothing much to this one: the way we tryto 'talk in sensible terms what else? ofwhat

we know escapes (and we want it to) from sense.Suppose, for example, we were born, as we saywe are,and died, in the end, after a reasonable life:

No would be all I could say to that, which Iwantmore than anything else that I could want.

Because Bronk has chosen to use his mind and to follow his.thought wherever it takes him, his poems often express profound skepticism and passionate longing. What is most important for me in these poems, however, is the voice Bronk has mastered for expressing the skepticism and longing pur capacity for thinking breeds in us. Many years ago I was listening to him read some of his poems; suddenly I protested angrily against his frequent use of the first person plural. I refused to accept the conclusions which seemed forced on me by Bronk's "we." As the years went by, however, ever, and I tried hard to think for myself, I came to see that when I talked to myself (and I cannot think without talking to myself) and when I generalized (and I cannot think without generalizing), I was in fact struggling for the voice in Bronk's poems and using "we" because I had to. I began to understand the poems and to see how beautifully they gave a voice to what we find hardest of all to bring out, the working of our thoughts at a level too deep for mere social intercourse or argument or persuasion; where we seem condemned to think as everlastingly isolated beings, everlastingly in search of words to express what we really are thinking.

Because he has found a voice for us voiceless, poetry which sets free what we think to ourselves but cannot bring out as we have thought it, Bronk reminds me often of Pascal. And because the power of his desire and the power of his skepticism free him from the poetic vice of piety, Bronk's Pensees also can become extraordinary religious poems.

VIRGIN AND CHILD

WITH MUSIC AND NUMBERS

Who knows better than you know,Lady, the circumstances of this eventmeanness, the overhanging terror, and theneedfor flight soon hardly reflect the pledgethe angel gave you, the songs you exchanged injoywith Elizabeth, your cousin? That was thenor that was for later, another time. Now Still the singing was and is. Songwhether or not we sing. The song is sung.Are we cozened? The song we hear is likethose numbers we cannot factor whose overplus,an indeterminate fraction, seems more than thepartwe factor out. Lady, if our despairis to be unable to factor ourselves in songor factor the world there, what should our joybe other than this same integer that singsand mocks at satisfaction? We are notfulfilled. We cannot hope to be. No,we are held somewhere in the void of wholedespair,enraptured, and only there does the worldendure.

Lady, sing to this baby, even so.

I should like to conclude with the great "The Elms Dying And My Friend, Lew Stillwell, Dead." In it are all the qualities I have noticed; above all, the profoundly felt sense of loss.

They are stripped and broken, which were sobeautiful,grey-groined, graceful, which held the balancesobetween lifting and lowering, they were thedancers who,at the height of a rise, hovered a little aloft,hung in the air, arms hanging, easy, poised.So often the focus of such attentive aweas we feel for the natural world, passing, theygrievethe fields for us, force us to findelsewhere solace, such as anyone findswhere there were never elms, nor misses them.Oh, it matters. It is not to say but whatit matters, but these dyings, yours even, sayyours:the riches of the world are infinite and itis prodigal. What is terrible isnot any death diminishes the world.Or time. The way we push it: wishing next 'weekwould come, or a year from now. Throwingaway.Does it matter so little? isn't it rather thatwe have it? Always. We have it. That there isnodiminishment. Never. Nothing. Help us.Help!

Harry Schultz is professor of English emeritus ofthe College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

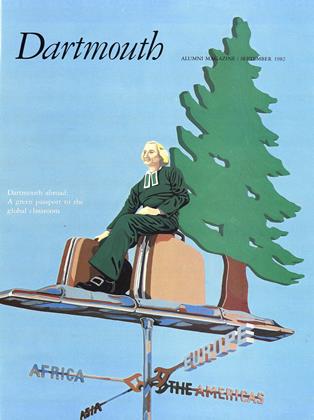

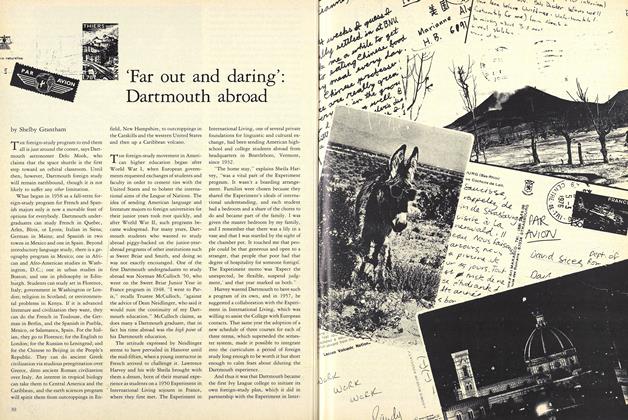

Feature'Far Out and Daring': Dartmouth Abroad

September 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

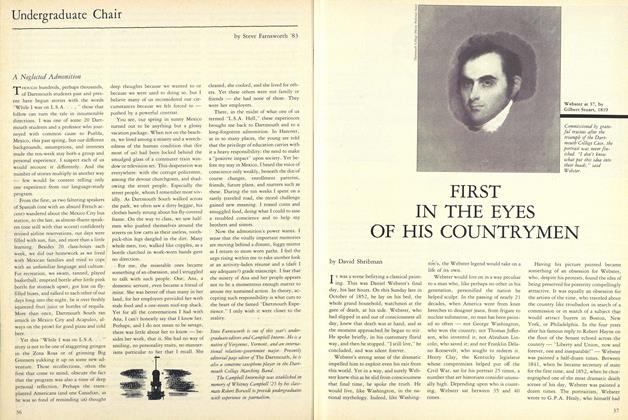

FeatureFIRST IN THE EYES OF HIS COUNTRYMEN

September 1982 By David Shribman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1957

September 1982 By Daniel M. Searby -

Article

Article"Man Better Man"

September 1982 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Sports

SportsHelp Wanted: Rising Sophomores

September 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

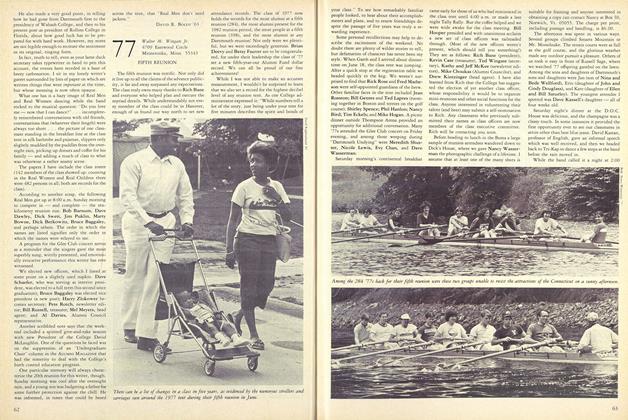

Class Notes1977

September 1982 By Walter M. Wingate Jr., Lindsay Larrabee Greimann '77

Harry T. Schultz '37

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

FEBRUARY 1929 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

JANUARY 1971 -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

January 1919 By C.F. EMERSON -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

OCTOBER 1969 By J.H. -

Books

BooksTHE NEW LAND.

OCTOBER 1967 By JERE R. DANIELL '55 -

Books

BooksGREEK PLAYS IN MODERN TRANSLATION,

December 1947 By ROYAL CASE NEMIAH.