By Harold LBond '42. New York: Doubleday, 1964208 pp. $3.95.

The memoirs of 20th-century generals make excellent light reading; and so do the innumerable volumes of military history which our century's two great wars have spawned. But no one can ever hope to find anything worth knowing about War from either of these two sources. Generals are naturally comic: as Harpagon is comic to the audience, though anything but comic to those over whom he has any authority. Military history is a wonderful manipulation of abstractions or a highly romantic kind of escape literature, but it demonstrates chiefly the ingenuity of military historians. If one wants to know what "War" means, there are only two ways in which he can find out. He can go to War himself, or he can read a book like Return to Cassino, which is the nearest thing to the actual experience of combat.

In War men hunt down and kill each other in a larger or smaller number of personal encounters. Any one of these, honestly and fully experienced, is War. The experience of more than one suggest to the thoughtful soldier that there is a wide range of possible types of death encounter; it does not alter the basic fact. Professor Bond has understood this and so has written a good book instead of mere military history. He has understood something else, too. The soldier who attempts to kill and to escape being killed in the attempt experiences some peculiar and permanent effects in himself. If his society has made him other than an animal, the descent to the state of nature which War requires compels him to see himself in a new and frightening light. War is the death encounter, but it is also the changes brought about in every decent soldier by the death encounter as it is anticipated, participated in, remembered.

Return to Cassino in its utterly unaffected manner of reproducing the experience of War gives the whole truth. Any soldier with combat experience will at once recognize the Tightness of the details of this book. Combat soldiers, however, are not the ones for whom such books are written. The problem lies between the soldier and his society. His life is passed in a world of which War is only a part; an embarrassing part which civilized societies do their best to disguise. Unless he is to be like Ernest Hemingway's Krebs, sitting on his porch, silent and alone, because his War experience has made it impossible for him to re-enter the world, the soldier must come to terms with the world by keeping silent and doing what he has to do or, better, by making himself and his fellows understood in such a way that the truth he and they know becomes a little harder to disguise. Professor Bond has chosen the better way in Return to Cassino and thus has done a braver thing than all the worthies did. Eighteen years after the Italian Campaign Professor Bond takes his family to Cassino. Among the formal and informal monuments to the men killed there, he begins to tell what happened as he knew it to his wife and daughters. The book ends in the cemetery at Nettuno, where the Anzio dead lie. His story over, its teller wanders by himself among the graves; his wife and daughters stand quietly aside, changed themselves by the story, knowing why they must at that moment stand aside.

Those who have been to War will marvel at Professor Bond's good fortune. Further thought will make them see that good fortune has nothing to do with it. We needed this book and we could not have had it unless a young, intelligent, sensitive, and above all courageous Lieutenant Bond had undergone the full experience of War and had then patiently endured the eighteen years of labor and meditation required to convert that experience into a good book.

Professor of English

Professor Schultz served from 1940-45 inthe U.S. Army. He was in German Prisoner of War Camps for two years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

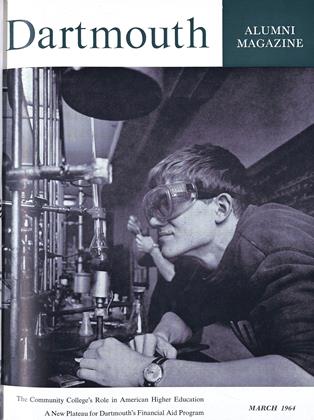

FeatureTHE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

March 1964 By THOMAS E. O'CONNELL '50 -

Feature

FeatureA New Plateau for Financial Aid

March 1964 -

Feature

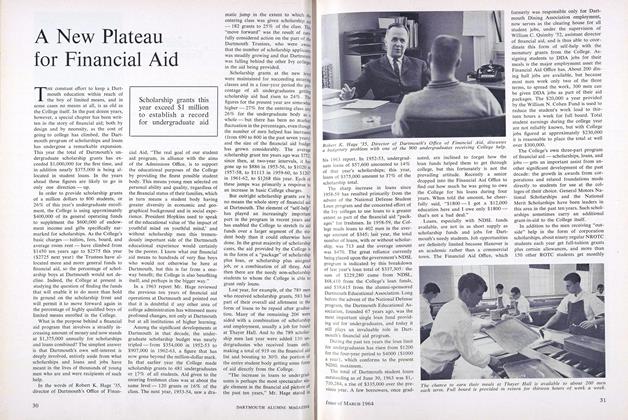

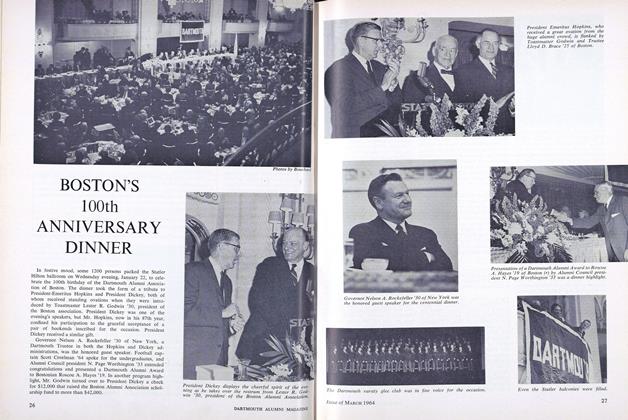

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

March 1964 -

Article

ArticleA graduate of 1804 who stood up for an American Culture

March 1964 By BEN HARRIS McCLARY -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

March 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

March 1964 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

HARRY T. SCHULTZ '37

Books

-

Books

BooksThe Story of the Western Railroads

August, 1926 -

Books

BooksFACULTY NOTES

MAY 1927 -

Books

BooksSUBMARINE! THE STORY OF UNDERSEA FIGHTERS

January 1943 By Bernard Brodie -

Books

BooksThe Principles of Sociology

May, 1924 By John M. Mecklin -

Books

BooksNotes on an expatriate's look homeward and on a bookman in a vast, sparsely inhabited region

October 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksA MISTAKEN IDENTITY

JUNE 1932 By W. M. McCombs. '33