I HAVE thought that it might be profitable to begin with the assumption that a good many of you gentlemen in this room this evening personally expect some day to occupy a position of management and that you may, therefore, be assumed to have more than a passing interest in the individual responsibilities of such positions and in the collective responsibilities of the management group toward the society of which it is a part.

When I was at your age and stage in the educational world, 110 one ever gave me any very clear notions on these points, and, if I am to be honest, had they done so, I should probably have paid no more attention to their words than you will pay to mine. Thus there battles within me tonight two urges: one of which says "Why not let them find it out the hard way?", and the other, the urge to lecture the young. From your own experience with parents, it should not surprise you to learn that the latter has won out by a very large margin.

Let us begin our examination with the picture of the average member of this class as he is engaged in a management job twenty years from tonight. By that time you will have been married a good many years; your family will have arrived; you will be in a rut in your job, and you will be in a rut in your home. If you work for a large corporation, your life will be consumed by such monumental concerns as, "Do I get Bill's private office when he retires next year?" or "When the company car met me at the airport last night, they sent the Ford instead of the Cadillac - I wonder if that means I'm not going to get a raise." Generally speaking, however, your rut, because it has become familiar, is therefore comfortable and reassuring to you, and your worries provide you only with a faint air of excitement. Your work you will normally do well by the accepted standards of your company, and you will hardly think about it actually. And it will make you feel really a part of the group and close to the Big Wheels of the corporation to complain to your fellow workers about the "lousy unions," and "lousy government," and the "lousy competitors." You will dictate all your letters with the same phrases endlessly repeated; you will make the same practical compromises; and, who knows, pretty soon you will probably end up as boss.

Now, in your home, you will probably start off as boss, but you will not end up as boss. And that may be why your wife will ultimately come to feel that you are more ardently married to your job than you are to her. You could have been boss in your home, but you will voluntarily abdicate soon after your home is started, and why? Because you will say that you're tired. You are too tired to help discuss the problems of your home; it's her job to settle them. You are too tired to play with the children, too tired to help with their homework. Twenty years from tonight the average one of you employed in a management job will be half alive - and that is only a polite way of saying half dead.

Now there was a famous sermon preached on this subject. John Donne preached it on Easter Sunday in 1619. He said, "We are all conceived in a close prison, and all our life is but a going out to the place of execution - to death. Now was there ever a man seen to sleep in the cart between the prison and the place of execution? Yet we sleep all the way; from the womb to the grave we are never thoroughly awake."

SINCE, therefore, this statistical you of the future will be only half alive, he will most probably be wholly unaware of the true nature of his responsibilities as a manager. For all his goals of existence will be of the same sort; they will be expressed either in terms of more things, or they will be expressed in terms of more time. High in your dreams of things required to make you happy will be a bigger house, or a Cadillac, or a private office, or, if you have a private office, you will want a carpet on the floor. Or perhaps you will be after a title. Or when you reach your forties, you will start chasing time - running to the doctor with imagined symptoms, talking about how you must soon start to take things easier, preoccupied with the stretching out of your own allotted time as meanwhile it slips unused through your fingers - as if you were a puddle butterfly that lives and dies in an afternoon, and never really takes one good flight to see what his wings will do but instead spends his whole afternoon trying to live five minutes more.

Now what have you learned here at Dartmouth? Have you learned that the men of history whom you most admire and the men whom you want most to emulate are those who possessed the most and who lived the longest? With your mouths you will tell me that the answer to this question is "no," but with your lives you will in all probability answer it "yes." The real answer is of course the answer that you will make with your lives, and you now have your best time, your best chance, to reflect on this. Were they the silly people of history, the men who accumulated nothing, spent their talents wildly? The composers - Mozart, whose 200th birthday we celebrate soon - or the poets - Keats who was dead at 26, and Chatterton who had made his contribution and was gone even before he had reached your age? Or the explorers who never returned? Or the heroes, like a college classmate of mine who so deliberately offended Hitler that, when his execution was ordered, Hitler instructed the hangman to keep him alive for sixty minutes and took movies for his own pleasure? Are these the silly people of history? With our minds we know that they are the persons who have shaped our age, and we know how they did it. Every one of them recklessly spent his talents and his time, and lost himself in something - poured himself out. But. you and I, who are not inclined to put out more than we think we are paid to do, who, given so little time, yet spend so much of our lives devising ways to kill time, consider that these men are more to be admired than emulated.

Now what has all this to do with the responsibilities of management? Just this. Essentially a manager is one kind of leader, and in that respect the profession of manager is no new profession. While its appearance seems new in history, yet in its core it is a very old profession. And the common characteristic of the classic leader has always been a capacity, above that of normal men, to spend himself, to pour himself out, to devote himself with a single mind to the aims of his leading. Unless you and I understand this fact with something more than our minds, we cannot come close to understanding the responsibilities of the manager. Note that I did not use the title of my assignment tonight - "The Responsibilities of Management" - I said "the responsibilities of the manager." For we must first understand the responsibilities of the manager before we can hope to understand the responsibilities of management.

Let me begin with the assertion that the most important thing to understand about today's business manager is that he has in his possession a very considerable amount of power over other human beings. Perhaps you are surprised that I don't say power over dollars, or over a great quantity of physical assets. This latter he has, of course, but the power over things - the dollars or the assets becomes significant and worth our discussing only when we conceive of the things as belonging to and being important to some individual person. So the manager has power over other human beings, both as to their material possessions and as to their time and the way they spend it.

Now this does not necessarily mean that he is "responsible" for the use of his power, for the dictionary reminds us that the word "responsible" means "accountable to or answerable to" someone for something. Ancient kings and despots, as you know, had enormous power over other human beings, but more often than not they felt no responsibility in the use of their power. They believed their power was theirs by right of ownership, and they felt accountable to no one for its use. True owners do not feel particularly responsible for what they own. I have a 12-year-old daughter; she might on occasion have a piece of paper on which she has written some matter which is of importance only to herself, and she might by accident tear it up and destroy it before she means to. This may upset her, but the matter of responsibility does not arise at our family dinner table that evening. Now let us suppose that this same act of destroying this same piece of paper is accomplished by one of her sisters, to whom she had entrusted the paper. The whole family immediately finds itself up to its ears in a discussion of the matter of responsibility. Sister No. 2 is "responsible" to Sister No. 1 for tearing up the paper. Why? Because it didn't belong to her.

So if we assume, as we apparently do today, that the business manager is accountable and responsible to someone for the use of his power, then it may very well be that we mean by this that the manager is not the true owner of his power over people, and that his responsibility, therefore, is to the true owner. Now at last we may be getting somewhere. If we can find this true owner, we shall probably have a good start on the understanding of the true nature of his responsibility.

You might very well say that we have made a great deal of fuss about nothing, and that all we have to do is look at the corporation's organization chart. That chart says that you as a manager received your power by delegation from your superiors; so, therefore, the manager is responsible to his business boss. Let's chase this power and its delegation and re-delegation on up the chart. We finally arrive at the fellow who is increasingly referred to as the chief executive officer, which perhaps more accurately defines his job than either of the more familiar titles of president or chairman. But even this fellow, the chief executive officer, if we are to believe the chart, is not the final owner of management's power, because the chart asserts that his power in turn comes from the board of directors and that their power comes from the shareholders. And there the chart ends. Law and custom tell us that the shareholders are the owners, and we may therefore easily assume, as managers of the past almost always did and as many managers do today, that management is responsible to the shareholders in today's business society.

Well, you may say, "Why not?" There is only one trouble with this, and that is that this very clear conception, once held nearly universally in flawless perfection, is now beginning to show a few cracks around the edges. Management, which was once more confident of its responsibilities than it is today, now is beginning to feel an uneasy compulsion to put other interests ahead of those of shareholders, and to recognize responsibility to other owners. Let us take for instance the field of corporate giving. In the last ten years we have the new phenomenon of the business manager unilaterally deciding to give away the shareholders' money — for example, to institutions like Dartmouth. And some shareholder lawsuits have appeared, asserting that no business manager has a right to give away the shareholders' money — that it isn't his money to give away. The managers have tried to solace themselves and quiet the shareholders by making elaborate explanations as to the indirect benefits to the shareholder. But the truth is that these explanations are no more convincing than management's explanations of the importance of holding the January board meeting in Palm Beach. And such explanations tend to conceal management's growing feeling that in such giving to charitable or educational causes it is recognizing a responsibility other than that to shareholders, and in some respects at least precedent to that of shareholders.

EARLIER in this talk we made the assertion that the most important thing to understand about today's business manager is that he is in possession of a very considerable amount of power over other human beings. I might add to this another assertion. The manager has to have this power over other human beings in order to do his job. If the human beings under his direction don't do what he says, then he is a failure as a manager, no matter what material assets may be at his disposal, no matter what knowledge, what experience or capacity he may have as an individual. If the people who supply him materials don't furnish him the materials that he orders in the quantities and the quality and in the time that he requires, or if his workmen don't come to work when he says or leave when he says or spend their time as he says, or if his salesmen won't go where he says or call on the customers he wants them to call on — if all or any of these people, or other persons in his employ and subject to his power, do not respond to that power and to his orders, then the business manager is utterly helpless. For so complex and interdependent has become his world today that he can do nothing by himself.

Well, who is it that makes all these persons submit themselves to the manager's power and authority? The truth is that nobody makes them do it. His suppliers don't have to sell to him; they can, if they want to badly enough, sell to someone else, and often they do. The workers don't have to work for him; they can, if they want to badly enough, go and work for someone else. And so can the salesmen, for all these people who are under the power of the manager are free persons in our free society. Nobody makes them submit themselves to his power. So the power that the business manager has to have in order to do his job is given to him freely by the very persons over whom he uses it. And the most important thing, therefore, to understand in our society today about the responsibility of the business manager is that he is answerable, accountable, responsible first of all to the very people whom he manages. Of course he is responsible to other interests and groups too. His responsibilities to his shareholders are great and important. His responsibilities to his customers are formidable. But the essential and distinguishing characteristic of today's business manager is that he is not a personal worker; he is a man who can be useful and effective only through the work of other people. And, since these other people are free to give or to withhold their work, he must never lose his awareness of the fact that his powers have been entrusted to him by the very persons over whom he exercises them.

So the business manager begins to understand the true nature of his responsibilities when he starts with an awareness that his first responsibility must be to the very people whom he manages. You may now reply that the freedom of the worker is not very real and is only an apparent one. You can say that, after all, a man has to work some place, and that, while he may be theoretically free to move and work somewhere else, in fact he becomes tied tighter and tighter to his job as each year goes on. You can say his investment in his house ties him; his children and their school problems tie him; finally his seniority ties him, and his pension rights tie him. So perhaps he isn't perfectly free to quit his job. But he is terribly free in a sense that is even more important to the business manager, because he is free at any time to do less than his best work. And the distinguishing mark, after all, between a good company and an average company can be discovered when you find out whether the spirit and the atmosphere of the company encourage men to do their best work rather than their required work. The successful foreman, for instance, is the one for whom men want to work. The successful manager is the one for whom people voluntarily and freely do more than is required of them. And this is the reason why the manager's first responsibility is to the free people over whom he exercises his power and whom he manages.

THE next question should then be: What difference does it make? How does the acceptance of this idea make any noticeable difference in the way a manager runs his job or in the way a corportion conducts its corporate affairs? Does it make a difference, for instance, in the way a management deals with the subject of union labor?

Let us start off with the management that considers itself the owner of the business. That type of management says, "This is my business and I have the right to run it my way, and no lousy union is going to tell me how to run my business." This type of management writes clauses in labor contracts, if it is forced to sign one, which emphasize management's prerogatives. And it conducts its relations with the union on the basis of permanent war, never quite abandoning the hope that someday it will be rid of the union. The management and men, under this concept, are apt to live out their lives together, each seeing how little he can give, each seeing how much he can extract from the other. And this kind of management usually can prove to itself that it is on the right track, because all the evils of labor unions which it has anticipated actually come to exist in its own union.

On the other hand, the managers and managements which consider themselves answerable to their people might be expected on the subject of union labor to be sensitive to the realization that, as men form themselves into larger and larger groups, inequities do occur, injustices do happen, and confusion is born which renders men frustrated and unhappy regardless of the best efforts of all involved. They begin to realize that the best system in the world by itself will not suffice to see that individual injustices are corrected, wage scales fairly administered, discipline reasonably handled. As American business becomes larger and larger, the men who are subject to the power of management cannot be heard individually. These men in all too many cases can be heard only when they have banded together and acquired a power that commands management's ear and management's respect.

Of course there exist corrupt, racketridden and autocratic unions, and I myself have dealt with some. There also exist incompetent and arrogant managements, and you have read about them in the newspapers. But, while you read further in the papers about the tragic union-management situations that occur in this country, there also exist with little or no notice union-management situations of strong mutual trust, common purpose and genuine respect. Many managers will tell you today that they could operate neither as efficiently nor as profitably without a union. And such managers are not only sensible of the first responsibility of management as we have defined it tonight, but are genuinely held in industry to be uncommonly successful businessmen. This same concept of responsibility applies with the same force to the leadership of union labor, for the job of the leader of a great national union is the same in its core as that of the business manager. The labor leader's first responsibility is to the persons over whom he has been given power.

Unfortunately both management and labor kick their responsibilities around a good deal today, and, when they do, they get into trouble. An example of this is seen in the current comedy which is being played out in legislatures and Congress under the titles of "Slave-Labor law" and "Right-to-Work law." The Taft-Hartley Act, about which I must confess I don't know too much, except that I can be sure it is far from perfect, wasn't named the "Slave-Labor law" by the workmen, for whom it offers some measure of protection against their being pushed around by their union bosses. It was so named by the labor bosses whom it restrains, and all their tears have not yet convinced the voters.

By the same token, the "Right-to-Work laws" one might suppose to have been named by the workmen who were trying to gain the right to work, but no, these laws have been written and named by management, who wishes to be able to prevent a union-shop contract even when their men want it. In their attitudes toward these two laws, labor and management are still today acting like owners, responsible to no one. But in the rather cynical names that they have applied to these two laws they recognize that the public expects them to act more responsibly than they do, and that the public expects them to be responsible to and concerned for their people.

We have some more phrases that we work pretty hard today. One of these is "freedom" and another one is "private property." Let us see what different things these phrases can mean to our society, on the one hand, according to the way our "owner" type of management might consider them, and, on the other hand, according to the way our "responsible" type of management, as we have defined it, might look at them.

The term "freedom" to an owner means that this is my plant and that I should feel free to run it the way I want to, to fill the air with noise and smoke and smells if I want to. Now this concept of freedom is well understood by savages, beasts and small children. But this exclusive definition of freedom as my freedom - is this really what the Western world says it is fighting for? I don't think so. I think we are fighting for a more responsible definition of freedom.

We have asserted that the responsible manager knows that he is responsible first of all to those he manages. So he might be expected to understand that the term "freedom," if it has validity, means not my freedom but rather an awareness of and a sensitive concern for the freedom of the other fellow. A society concerned for the freedom of the other fellow becomes a society which can compel and win and change men. It becomes a society that is all the things we claim for Western society. And it becomes a responsible society.

The same is true of the phrase "private property." There is nothing new about a concern for my own possessions, but there is something new and compelling and responsible about a society concerned for the property of the other fellow. You can take the idea from here. You can decide for yourselves how the responsible management will respond to the claims of customers, or to the claims of the government and taxes, or to the claims of suppliers, or to the claims of the community in which it exists.

AND now what does a manager or a man agement have to do to discharge this responsibility? Certainly to discharge it a management must first of all be aware of it. And awareness means waking up. It means spending yourself on it, pouring yourself out on it; first of all, with genuine affection and concern for those who entrust their best years to your direction; second, with strong courage to evaluate and choose between competing inter- ests and to go down with your choice if necessary; third, realizing that the only sure thing in life is change, accommodating yourself to change at all times thoughtfully, but never giving it blind resistance; and finally you will cultivate the ability to work for and with others, which ability is the cement of our society.

Now I hope I have not dismayed you with this formidable notion about the business manager and his responsibilities. It is true that all too often the life of the average business manager today is char- acterized by ulcers, early heart attacks, broken homes, a feeling of frustration and futility. It need not be the case. And an understanding of the responsibilities of management is really at its core an unders tanding of the opportunities of management.

If you understand these, and if, when you have your opportunity, you seize it with faith and without counting the cost too carefully, then I can guarantee that you will find the rewards of management greater than you had ever hoped they might be.

AT the question-and-answer session of Great Issues, held the morning after his Monday night lecture, Mr. Miller discussed a variety of management and labor topics with the seniors. Following are several of the questions and replies, as taperecorded.

Question: How much influence do you feel the growing force of the labor movement has had in bringing people such as yourself to hold this enlightened viewpoint about the responsibilities of management?

Mr. Miller: I think a great deal of influence. And I'll tell you why. Management gets its best education in a bargaining session, because those members of management who personally participate in lengthy bargaining sessions and have their own points of view severely questioned cannot go through them without reaching new ground themselves. I think one of the less desirable tendencies in business is the delegation by management of the bargaining process to lawyers or staff members, because I don't know of any way in which to be tested better or to be educated more vigorously than to have the men in your own plant tell you what they think about you and the way you run the business.

Question: Adam Smith pointed out that the only trustworthy motive for a business man is self-interest, and that only if he is motivated by profits will he do work that will serve the public good. How do you reconcile this with your own subordination of the profit motive in the responsibilities of management?

Mr. Miller: I don't reconcile it. I just don't believe it.

Question: A previous speaker told us that unions should be formed even when workers are content, because the favorable conditions granted by management could be withdrawn at any time. Would you care to comment on that?

Mr. Miller: I think that in our society I would rather have a union than not. The only exception would be in a small plant. I don't know where the line would be drawn, but it is possibly true that a union might not be necessary at the level of an exceedingly small plant. However, when you start to put one layer o£ management on top of another, the reason why I would personally want a union is that, after you set up your chain of command, you then have got to have a means of short-circuiting the whole business, or you have lost touch with what is going on at the bottom of the chain. If the plant is of any size at all, I honestly don't think it is going to stay a contented plant very long unless it has a good, responsible union.

Question: What is your attitude toward the union shop?

Mr. Miller: Maybe the best way to tell you how I feel about the union shop is to explain the attitude that we have taken in our business toward that demand. Originally I thought the demand was a weakness on the part of the union, and I used to tell it so. I said, "You fellows ought to hold your members because they want to belong to you and not because they have to." And we refused for a number of years, after we were first organized back in 1936, the demand for a union shop. In the first place we said there aren't enough people in the bargaining unit who are voluntarily paying dues and turning out for your meetings. Then along came a year in which they put on a lot of pressure for the union shop, and we said we would agree to it under certain conditions. I will tell you what persuaded us. The classic argument against the union shop is the "Right to Work" argument. The average American manager feels that there is a character known as the "loyal employee," and this is a fellow who is supposed to figure that joining the union is a fate worse than death, and that he would rather starve, and all his family with him, than be forced to join the union. Well, this man is in the same category, in my opinion, as the Easter Bunny and Santa Claus. I've never found him. I believe I will recognize him the first time I run across a man who turns down the wage increase that the union bargains for him in the contract. And I have never seen anyone who turned down union benefits, which he really ought to do consistently if he believes this way. There is also his counterpart who exists in the mind of the labor leader, and that is the fellow who reads all the literature published by the C.I.O. and has devotions over it with his children every night, etc. He doesn't exist either. They are both fictions, from which both the manager and the labor leader get a lot of comfort.

Actually, the argument goes this way. The manager feels that these fellows are being forced to join something they don't want to join. And local bargaining committees feel the same fellows get the benefits of what they do as- a union, and that they ought to pay their share of the cost. You see, under present interpretations of the union shop, membership in a union need not be determined by the taking of an oath. In the average case, it is considered to be merely tendering the monthly dues in the manner arranged for. And the union membership considers that the business of a union shop is a matter of taking care of the free riders, the fellows who want the benefits but don't want to pay the costs, and they feel very strongly about that. I have some sympathy with that point of view, once the number of free riders is small enough. Now in a union that had a dues-paying membership on a voluntary basis of only ten per cent of the bargaining unit, I personally would resist the union shop, because I would feel that the union had not sold their people. ... In our company, when the union finally got over ninety per cent of the people in the union voluntarily and freely paying dues, we signed the union-shop contract, because the number of free riders was then so small. And we have never had to fire anyone over the union-shop provision.

In the proper circumstances, the union shop can be an aid to good relationships; and in other circumstances I wouldn't go for it.

Professor Robinson: Mr. Miller, I would hate to have you leave today without saying some of the things you said last night, after the lecture, concerning the problems you have with young men going into management, and the desirability of getting them not to be conformists. Would you care to say a word about that?

Mr. Miller: A question arose last night about the college graduate as he enters business. Someone asked what businessmen would like him to do that is different from what he does. Both Mr. Stoner and I said that we would like him to be more critical of the corporation than he is. He tends to swallow all of its policies uncritically; he tends to accept whatever the labor or sales or any other policy of the company is without really searching it on his own or making it his own. Now that doesn't mean that you want him to be a bull in the china shop; but it does mean that he has to understand, if he is a really mature person, the delicate balance between being a part of the team and at the same time never stop thinking for himself. It is hard to get the young man in business to be analytical and searching and critical about the business, and one of the things that a good corporation does, and one of the jobs of education that we think we have: to finish, is to educate the college graduate into thinking more objectively about everything with which he comes into contact in his new surroundings.

The fundamental reason for this is that the only unchanging thing about business is change. Every institution, every system, every way of doing things in a business is evolving, and, therefore, if a business is to move successfully, it must be in constant change and it must be managed by experimentally minded people.

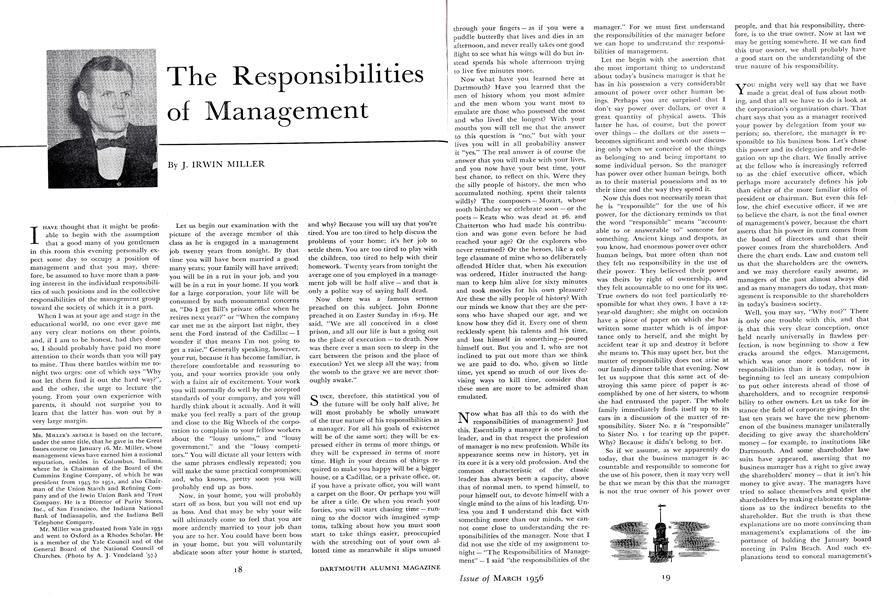

MR. MILLER'S ARTICLE is based on the lecture, under the same title, that he gave in the Great Issues course on January 16. Mr. Miller, whose management views have earned him a national reputation, resides in Columbus, Indiana, where he is Chairman of the Board of the Cummins Engine Company, of which he was president from 1945 to 1951, and also Chairman of the Union Starch and Refining Company and of the Irwin Union Bank and Trust Company. He is a Director of Purity Stores, Inc., of San Francisco, the Indiana National Bank of Indianapolis, and the Indiana Bell Telephone Company. Mr. Miller was graduated from Yale in 1931 and went to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. He is a member of the Yale Council and of the General Board of the National Council of Churches. (Photo by A.J. Vendeland '57.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Sets '56 Fund Goal At January Session in Minneapolis

March 1956 -

Feature

FeatureCarnival Post-Mortem

March 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

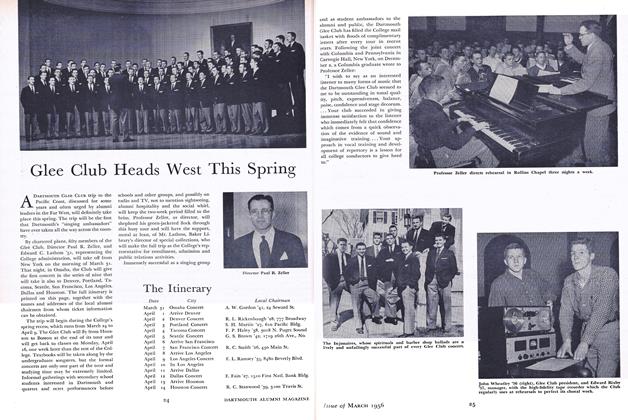

FeatureGlee Club Heads West This Spring

March 1956 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1956 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1956 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES JR., TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE

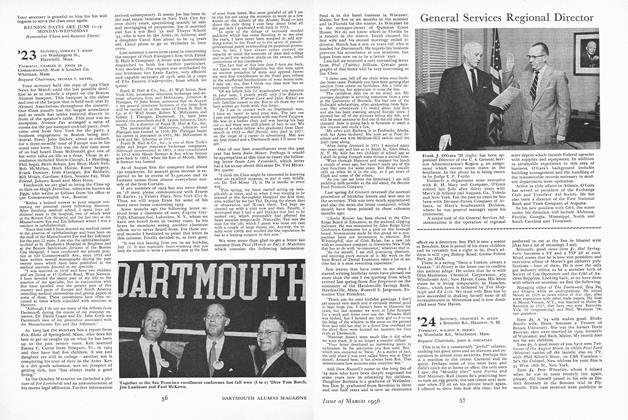

Features

-

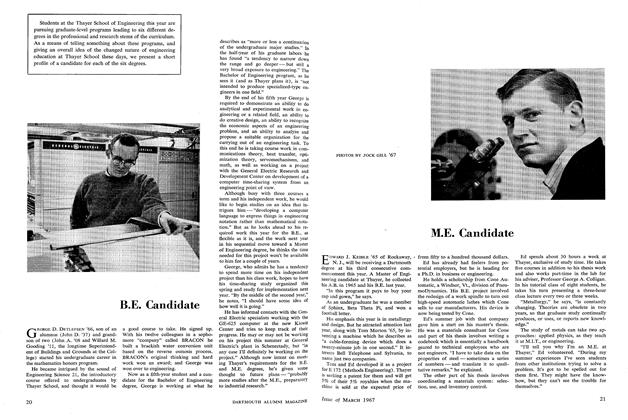

Feature

FeatureBE Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

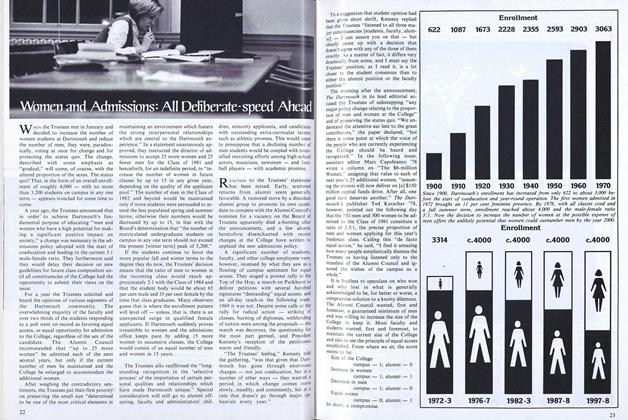

FeatureWomen and Admissions: All Deliberate-speed Ahead

March 1977 -

Feature

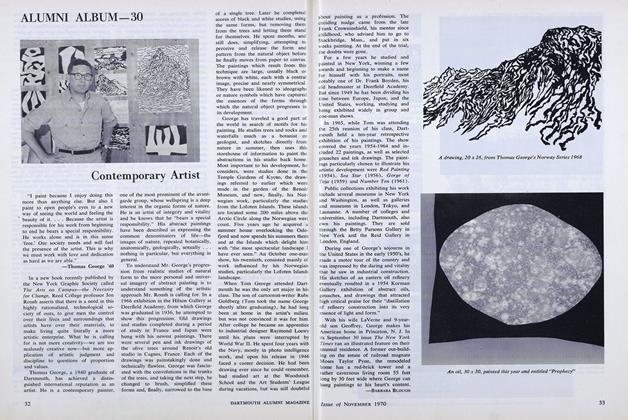

FeatureALUMNI ALBUM-30

NOVEMBER 1970 By —BARBARA BLOUGH -

Cover Story

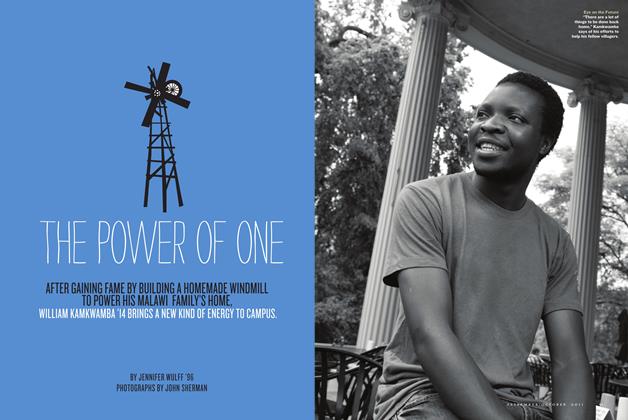

Cover StoryThe Power of One

Sept/Oct 2011 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureThe Lady and the Truckers

October 1978 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Cover Story

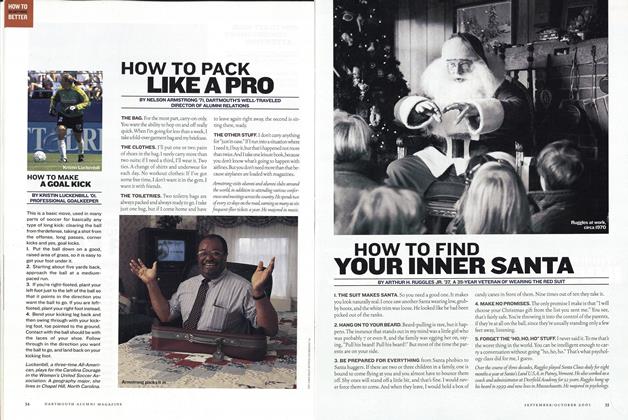

Cover StoryHOW TO PACK LIKE A PRO

Sept/Oct 2001 By NELSON ARMSTRONG '71