The Address at Dartmouth's Honors Convocation

FRANK MUNSEY PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, BOWDOIN COLLEGE

In remarks which, I hope, will prove to be characterized by an instructive rather than a repellent chauvinism, I should make it clear at the outset that I have no intention of defending those empty subjects and programs, for example life adjustment, which like pillars of salt, ornament the landscape of the American educational wastelands. I am not concerned this morning with what is taught and learned but with the manner in which both processes are carried on. For I think in this area we can discover an American emphasis and an American note.

Those who have been through the European schools, or have sympathetically observed them from outside, are prone to assert that American students don't know anything. They come to college unprepared in this, that, or the other thing. For explanation this defect is usually ascribed to our national negligence in matters of the mind. Neither the children nor their parents want the former to do their home work; and the inertia carries over into learning at the college level. It rarely occurs to critics of this temper that perhaps another national characteristic explains the situation. Americans, on the whole, have not wanted the educational system to emphasize the accumulation and acquisition by students of factual information. They have preferred that American learners learn how to find information and how to use it. For this there were undoubtedly many explanations. For one thing so much of inherited learning seemed clearly useless to the tasks and needs of a country newly settled in the new world. In colleges where classes were held under trees and college presidents might have to shoot Indians, the mastery of the Greek language, the refinements of may and can, and the memorization of ten noble rivers in Siberia seemed somewhat of an irrelevance. But I am not on this platform to elaborate a frontier theory of American education.

Deeper and more powerful as a transforming or shaping factor were some aspects of American individualism: the individual was responsible for determining his own achievement and own fate, for meeting, as a person, both the rewards and punishments of life. Americans, because of their ideological heritage, believed in self-help. Soon after the Civil War, W. T. Harris, the most gifted and influential of American educational thinkers

in that generation, was saying of American education: "A monarchy, aristocracy, or theocracy found it very necessary to introduce the scheme of external authority early. We who have discovered the constitution under which rational order may best prevail by and through the enlightenment and freedom of the individual, we desire in our system of education to make the citizen as independent as possible from mere external prescriptions. We wish him to be spontaneous - self-active - self-governing.... We give the pupil the conveniences of a perpetual selfeducation. With the tools to work with - and these are the art of reading and the knowledge of the technical terms employed, he can unfold indefinitely his latent powers.... The attempt to pour into him an immense mass of information by lectures and object lessons is ill-adapted to make the practical man, after all."

The reasons for this novel and American note did not include the advent of natural science into the curriculum and into learning. Scientists and their fellow travelers who have rightly ascribed to these subject matters so much that was transforming and revolutionary should on this score be humble. Science, like everything else, had to be taught in a new way and in accordance with the new spirit. It is significant that the new schools like M.I.T. were saluted because in them the students themselves found out the facts of science; they were not told in lectures or in demonstrations staged before them by professors. The key note was the laboratory, not for the professor, but for the whole class. In other subjects the emphasis shifted away from the recitation in which the student who has mastered most exactly the wording of the textbook was the one who got the highest grade. As one bewildered Harvard alumnus informed William James: "I can't understand your philosophy. When I had philosophy we had to commit it to memory."

The result of the American attitude is tangibly visible in the library building. Why have Americans developed the most highly satisfactory library science in the world? Because, I believe, they use libraries instead of memories as instruments of learning. Another evidence is our classroom vernacular. A professor does not lose caste when he says to an over-brilliant undergraduate inquirer, "I can't tell you the answer but I can tell you where to find out." He is subscribing, whether he knows it or not, to the ideal of "Learn American!"

The obligation of the college to the native American tradition does not stop with adopting the Dewey decimal system of cataloguing books or with training its teachers in glib evasive action. It must emphasize in the teaching process the best educational methods for self-help. By this I do not mean it should employ only dynamic classroom personalities who can get attention from their hearers. Nothing is easier to do than devise stunts for this purpose. If, as Miss Anna Russell says, you must be something of a dish to be a popular singer, you must be something of a college character to be a popular professor. You can do it by wearing spats and carrying a cane and have, as inseparable companion, a dog who will snooze under the desk during the hour. If you are a Dartmouth professor this familiar had better be a run-down mongrel with the name of "John Harvard." Whatever the temporary success of these devices, they are bound to go under when closed-circuit TV takes over the task of instruction. Since this off-campus agency can provide the best stunt masters and attention getters, there is bound to be technological unemployment among merely local practitioners.

Do not think for a moment that this prospect is mere whimsy. Doctor A. C. Eurich, vice-president of the Fund for the Advancement of Education, a quaintly named organization whence the good dollars if not the good ideas come, recently urged "that educators think in modern, twentieth century terms. He outlined a plan to bring America's greatest teachers into college classrooms through television, kinescope, and film."

He also challenged the educational theory that the pupil-teacher ratio should be kept low. "Where does the notion that twenty-five students are enough for a teacher come from? This is an old, shopworn belief, handed down to us from an early era before the day of telegraphy, photography, motion pictures, microphones, radio, tape recorders and television. A good teacher need not be limited to twenty-five, fifty or any set number of students." If the inquiring Doctor is really ignorant as to where the idea of smaller classes comes from, I can tell him. It comes from experience. It comes from the realization that education is not a one-way street from teacher to student but is a reciprocal relationship between the two. Not that the student ordinarily educates the teacher - far from it - but that the student with the aid of the teacher educates himself. Dr. Eurich's ideas on this score are so divergent from American experience and purpose they deserve the epithet "un-American," in the genuine sense of the word.

I share Dr. Eurich's aversion for the class of twenty-five not because it is too small but because it is too large to "learn American." Let us lay aside wiggle and wobble and recognize that the nearer instruction approaches an individual relationship the better the quality of education generated. If we must keep the proof within the framework of historical quotation, we can resort to President Garfield's famous preference "for a student at one end of the log and Mark Hopkins at the other."

Three decades later, Woodrow Wilson, who had recently introduced the preceptorial system to Princeton, was saying at the inauguration of Ernest Fox Nichols as President of Dartmouth: "If you want to know what I know about a subject, don't set me up to make a speech about it, because I have the floor and you cannot interrupt me, and I can leave out the things I want to leave out and bring in the things I want to bring in." To his mind, instruction in genuinely small groups was the means to set the college on fire. It is a pathetic irony that to refresh this system of education, sponsored by Garfield and Wilson, both of whom were college presidents and presidents of the United States, American colleges and universities in the twenties should have had to turn to the tutorial system of Oxford and Cambridge as their pattern. That was the era when an acquired English accent, plus-fours, and a knowledge that a "scout" was not equivalent to Kit Carson dominated the American campus.

It does not discharge the obligation of an institution of higher learning, particularly a liberal arts college, as Dr. Eurich would have us believe, to employ teachers who believe in teaching and can interest and hold the interest of students and put such individuals in front of a class, in person or on film or tube: the college must provide institutional arrangements by which students can learn to help themselves. Only the cynic will argue that the college should use the worst methods of teaching in order to force students into some self-reliant activity in order to get their money's worth.

Self-help is not confined to "the four happiest years of your life," as the banal quotation puts it. It is the foundation of later education. For one thing the factual information acquired in college has some carry-over value. I once was surprised and delighted by a Dartmouth alumnus who confessed to inheriting from his undergraduate years a lifelong enthusiasm for Alexander Pope and who quoted to me with immense relish the line from the Dunciad, "And universal darkness covers all." More importantly your undergraduate years should have taught you that learning is a love affair rather than a bore or a chore. I am here to defend the proposition that there is more creativity in finding out something for oneself and clothing it with life, meaning, and delight, than there is in having a baby, apparently such an übiquitous and urgent "felt need" of the younger generation. The current obsessive dedication to increasing the American birth-rate represents the triumph of an allegiance to a misguided therapy over the desire for achievement of a more distinctive, individual sort.

In honoring by this occasion the undergraduates before us, the College is not honoring the shallow and transient prestige of the campus celebrity, the "big wheel" and, in the case of Dartmouth, the "big earnestness." For if we are not on our guard, sincerity, that concept so beloved by hucksters and undergraduates, will displace urbanity of mind, by which I mean an alert and appreciative response to persons, situations and ideas, as our educational objective. Luckily we honor you today not because you are men of good influence or good will, or because you are socially adjusted and civicly responsible. We honor you because you have demonstrated an ability to make progress in learning. If the world is to go on, some one must know how the UN, an atom, or a syndrome is organized; you are the ones. Furthermore, if you have learned American, you have learned in the area of knowledge how in future to "unfold indefinitely your latent powers," and, if you are so convinced, thus make a contribution to the wider culture of which you know yourselves to be a part.

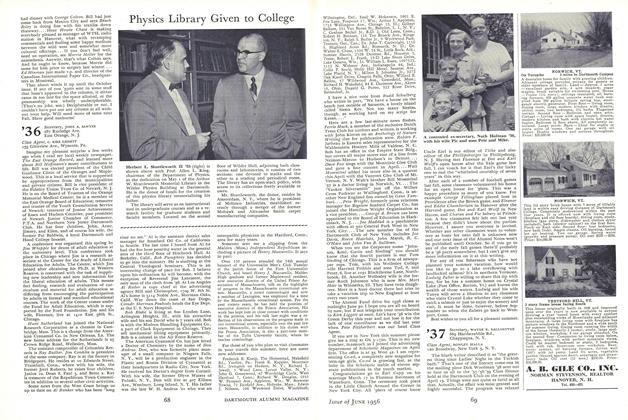

Dr. Kirkland (center, with folder) marching in the academic procession beside Acting PresidentMcLane. Prof. John Hurd '21, senior class adviser, is the marshal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

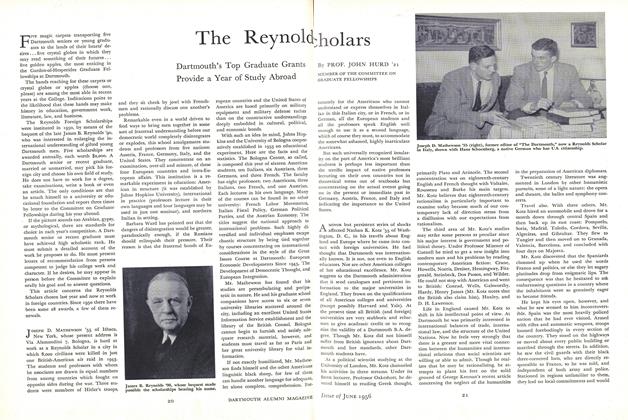

FeatureThe Reynold Scholars

June 1956 By PROF. JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

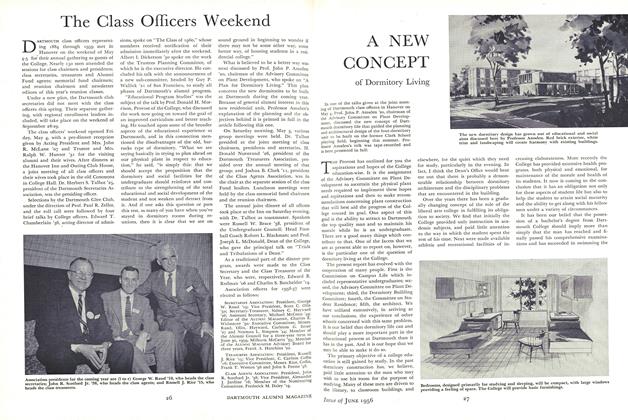

FeatureA NEW CONCEPT of Dormitory Living

June 1956 -

Feature

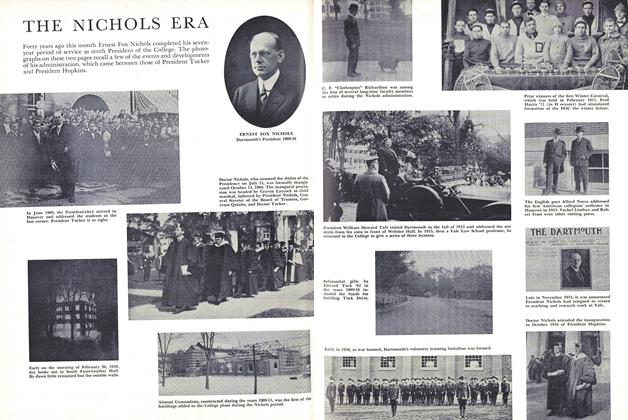

FeatureTHE NICHOLS ERA

June 1956 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

June 1956 By JOHN A. SAWYER, C. KIRK LIGGETT

EDWARD C. KIRKLAND '16

Features

-

Feature

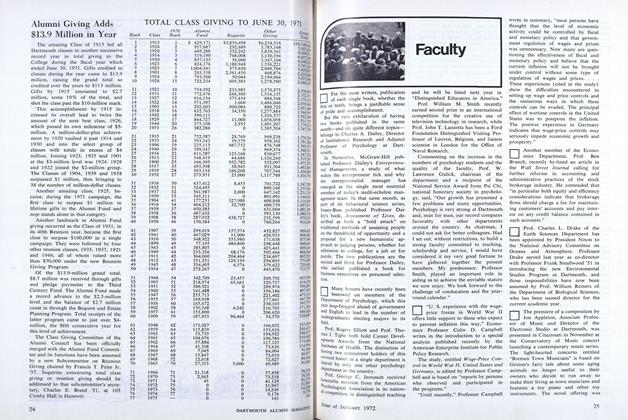

FeatureAlumni Giving Adds $13.9 Million in Year

JANUARY 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Untouchables

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCan the Family Doctor Recover?

NOVEMBER 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTo die loving life

DECEMBER 1998 By Diana Golden Brosnihan '84 -

Feature

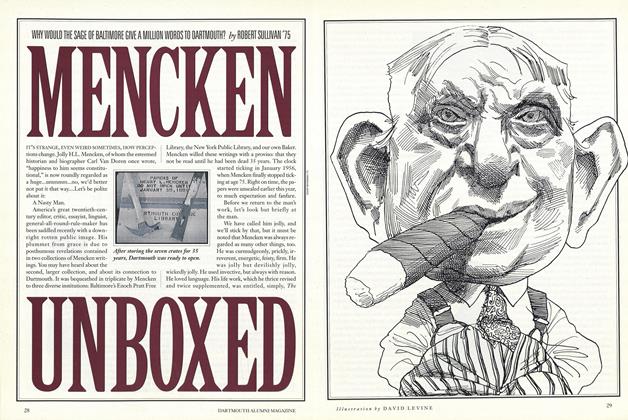

FeatureMENCKEN UNBOXED

OCTOBER 1991 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

MARCH • 1985 By Shelby Grantham