Business as a Social Service

October 1956 THE HON. RALPH E. FLANDERS, LL.D. '51, U.S. SENATOR FROM VERMONTBusiness as a Social Service THE HON. RALPH E. FLANDERS, LL.D. '51, U.S. SENATOR FROM VERMONT October 1956

Following is the nearly complete text of the address delivered by Senator Flanders at the Tuck School commencement exercises on June 3, 1956. Senator Flanders, who is a member of the School's Board of Overseers, discusses the subject of his address at greater length in his recent book, A Letter to a Generation, published by the Beacon Press in May 1956.

THOSE of us who are in business, or are about to be, as is your case, do well to clear our minds on the social aspects of capitalism. We should be clear as to whether it is a moral activity, justified by its social service. That question I propose to discuss with you this morning. . . .

Capitalism is denounced as organized selfishness. It is denounced as the seizing of power by the rich to enslave the poor. The capitalist is supposed to hang his head in the presence of the critic, presumably without a word to say in his own defense.

There really is much to be said for capitalism and even more for most capitalists, and this is a good place to say it.

The profit motive is a decisive factor in determining the economic activities of the modern man. Speaking broadly, that which is profitable to him he will do. That which is not profitable to him he will refrain from doing. These are the bold bare bones of the system. The system is neither moral nor immoral, having grown up by impersonal evolution in our Western society. Within the system MEN may behave morally or immorally. How do they behave?

First let it be said that modern man does not act as boldly and as baldly as my definition of the system would imply. For one thing, he is restrained by laws which put all sorts of impediments in the way of unsocial selfishness. In the second place, he is restrained by an intellect which looks for long-range profits rather than for quick ones which are dangerous and destructive, quite likely for his own future as well as for that of the people with whom he deals. Finally, modern man is a moral man to a degree which has never before been attained in economic history. There are many things which he cannot do without despising himself as well as subjecting himself to the criticism of others.

In an ideal capitalistic society the profits go to the businessman who provides the public, his customer, with the highest value in goods and services for the lowest price. This is achieved through a constructive type of competition; and it is to make sure that competition is constructive that our Federal Government has set up laws controlling it. If the businessman obeys the law in letter and spirit, if he is willing to venture and to compete, then he serves the public to the highest degree and is entitled to reward in the form of profits from such useful services, and with the reward goes an expanding opportunity for service. By this means the highest individual abilities are harnessed to meet social needs and to solve social problems.

Furthermore, profits do act as the great organizing principle of our industrial system. The dairy farmer of my own state has the feed for his cattle brought to him and his farm machinery provided him through the profit system, though he may live in a remote corner of a rural county. Taxes derived from the profits of the system have built hard-surfaced roads in his neighborhood. The profit system sends trucks to gather his milk and take it to the collecting centers. From here it goes by truck or railway car to great and small cities lying to the south and west. Here again it is taken in hand by distributors, who leave the bottle of milk on the family doorstep. The price-profit system leads to a higher supply of milk when the demand is great and to a shorter supply if the demand at the going price is overreached.

To operate such an elaborate system of production and distribution would be an impossible task if it were done by arbitrary orders from a central body somewhere. As: it is, the milk flows smoothly — not always or even often at prices that satisfy the producer, not always or even often at prices agreeable to the consumer. From time to time a distributor goes into bankruptcy; so he is not happy either. All of this looks like a most uncertain process, but the milk itself flows smoothly from the cow to the bottle-fed baby.

Finally, profits perform still another function in addition to that of organizing production and distribution and of rewarding efficiency in those fields. From the reservoir of profits is drawn the new investment which finances the expansion of industry and trade to serve a growing population, and the technical improvements which are the basis for increases in our standard of living from generation to generation.

All this the profit system does. Communism has not been able to show a similar record. The doctrine of "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need," noble though it sounds, has never worked. We are having confessions of failure from the Soviet Government officials.

BUT the capitalist system cannot work without effective counterpoise. Both economically as well as politically we live in a system of checks and balances. Checks are necessary and available to balance the capitalist in our system.

In the first place, we have an alternative method of economic organization ready to take hold if, where, and when the conventional profit system fails. That alternative is the cooperative system of production and distribution. It is still a profit system, but one in which the profits, if any, are distributed over a greater body of people the members of the cooperative undertaking. The continued existence and health of cooperative business is important to the country. It should, however, have no artificial advantages over private industry and trade. It should approach the Swedish system, under which the terms of competition between private and cooperative business are set as nearly equal as possible. Only when this is done can the cooperative serve fully its social purpose as a counterpoise to corporate profit.

Another counterpoise is organized labor. It is important that the worker not be helpless. It is important that he be able to negotiate on even terms with the employer. It is not well if either employers or organized labor have the balance weighted in their favor. Wisely led unions will help enforce respect for the moral law. Unwise union leaders who themselves ignore it will in the long run bring their membership to disaster. Here as everywhere the moral law rules.

Recognition of this becomes the more important as the present increase in the strength of organized labor shifts the balance of power into its hands. That power will lead only to confusion and material loss if it challenges the moral law. Fortunately there are many labor leaders who recognize this.

In our day and in our land the overriding material counterpoise to the profit system is the income tax. This can be carried to the point where the capitalist receives only a fraction of the profit that would have been available to his father or his grandfather under the terms controlling our economic life a generation or two ago. The capitalist in management is approaching the point where his dollar earnings in salaries or profits are little more than chips in the game which he surrenders from time to time before a new game is started. This gives emphasis to the fact that the intangible elements in the profit system are at least as effective for encouraging enterprise as are the retained dollars of the investor and business manager.

Yet the counterpoise of income taxes, corporate and personal, easily can be carried to a point where it ceases to be in the public interest. It is unwise to tax so heavily as to shut off the private contributions to all sorts of desirable projects in health, education, and other fields in which it is important that the activities should be left not to the government alone but to the free development of individual imagination and ability.

Above all the income tax must not be carried to the point where it dries up the sources of risk investment so that the standard of living of the increasing population cannot be maintained and the advantages of new sciences and techniques cannot be applied to the raising of that standard.

WE have done astonishingly well in these respects. Checks and balances, trial and error have served us well. The time has now come when the needed advances can best be made through an expanded and statesmanlike resort to the second of the approaches to the moral law - the long-range, intelligent self-interest of management and employees. This advance will be assured if the way is illumined by the light of the moral law.

Here also lies the great unsolved problem of tree capitalistic prosperity. How can we have full employment without inflation? It is an unsocial remedy for inflation to maintain a body of unemployment, however small. Here again is the opportunity for industrial statesmanship.

There is a certain natural pragmatism brought about by the unity of righteousness. The prophet and the saint see the goal with clear vision and make direct for it. The man of intellect, seeking for longrange self-interest, follows more slowly in the same path. The rest of us bumble along in crooked paths or pathless briars, trying this and that, being obstructed or permitted to advance. Laboriously and inefficiently we make progress toward the same distant goal.

Marx was blind to all this. His blindness came in large measure from living in other times and in other places. With imagination he might have conceived the possi- bility of a healthy constructive capitalism. Living nearer in time but farther in place, Lenin and Stalin might have made a better estimate. But they did not. They followed the judgment of Marx. They likewise were mistaken.

The strong, binding, enduring element in our capitalism is its correspondence with the moral law, however limited that correspondence may be. It matters not whether the recognition of the moral law comes to the businessman by revelation, by intelligence, or by trial and error. By whatever route it arrives, it works.

Finally, let it be admitted that capitalism is indigenous to the conditions of Western civilization. In its fullest development it is indigenous to America, where boundless natural resources and a pioneering population furnished the soil whereon it developed its greatest success, humanly speaking.

We cannot be sure that capitalism can be exported in its complete form. We cannot even be sure that the democracy which is its political foundation can be exported to other countries which do not have in their past history the generations and centuries of growth of free institutions.

We can be sure that, in order to succeed, any social, economic, or political system must have its basis in the moral law, which is recognition of the worth of the individual soul. In practice this means that the government shall exist to serve the people, not that the people shall exist to serve the government. We must avoid trying to force other peoples, and particularly ancient civilizations, into our own mold. They may be broken in the process.

This is the year of a Presidential election. Your speaker is a politician of sorts. Will he be pardoned if he closes this talk with some reference to the political requirements for carrying out the social responsibilities of business?

There must be among our Federal legislators and in the Administration a determination to support large, profitable employment. This is a basic requirement. It is right and proper for employees to negotiate for higher wages, shorter hours and better working conditions. Yet no agreement made with employers can provide these benefits unless business is active and prosperous.

Some of us in government feel a special responsibility for preserving the conditions which make benefits possible. Such politicians are seldom classed as "liberals.' More likely they are called "conservatives," which is a praiseworthy term, or even "reactionaries." Nevertheless, whatever we are called, a sufficient number must devote themselves to the maintenance of employment and production.

You too, in business, may find yourselves at certain times and in certain circumstances denominated unpleasantly. If you follow the moral law, you may be thought an "odd duck" or at least impractical. Be assured, however, that there is no other road to a solid success.

As you go out from here, you will fortunately find in business a greater acceptance of the basic principles of success in human relations than the world has ever before known. Move, therefore, intelligently and confidently.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

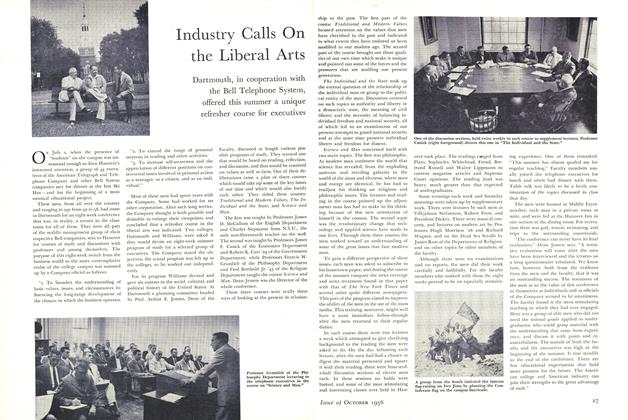

FeatureIndustry Galls On the Liberal Arts

October 1956 -

Feature

FeatureHE DUG DEEP TOO

October 1956 -

Feature

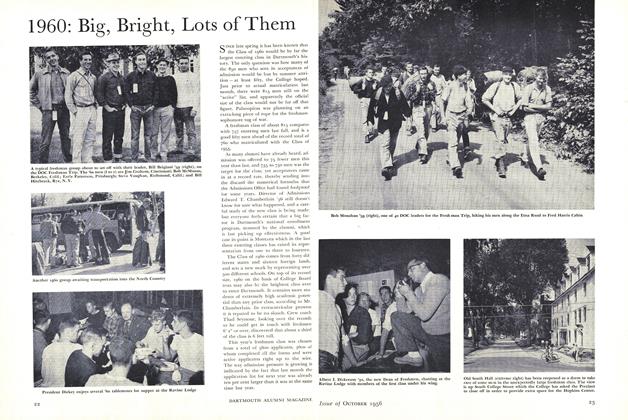

Feature1960: Big, Bright, Lots of Them

October 1956 -

Feature

Feature"Dartmouth Visited"

October 1956 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

October 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS

Features

-

Feature

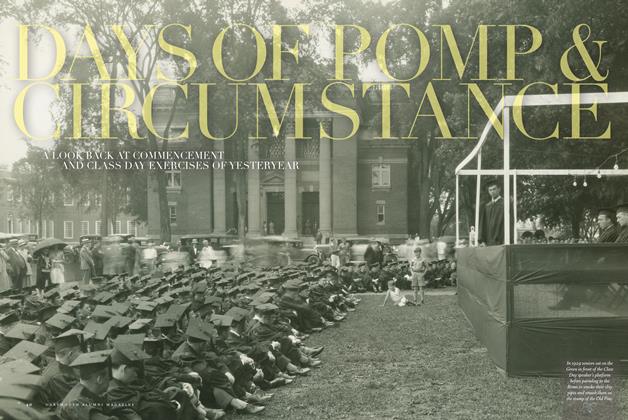

FeatureDays of Pomp & Circumstance

July/Aug 2013 -

Feature

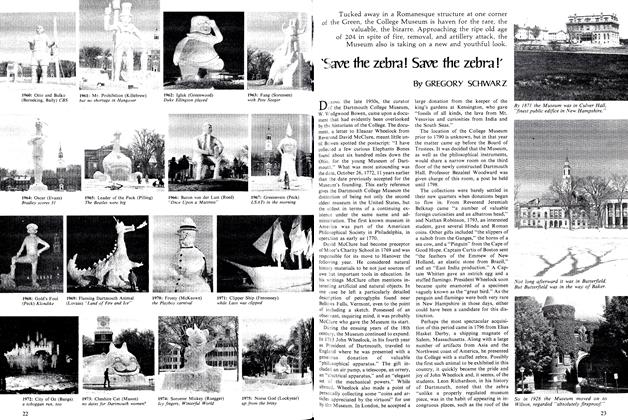

Feature'Save the zebra! Save the zebra!'

February 1976 By GREGORY SCHWARZ -

Feature

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

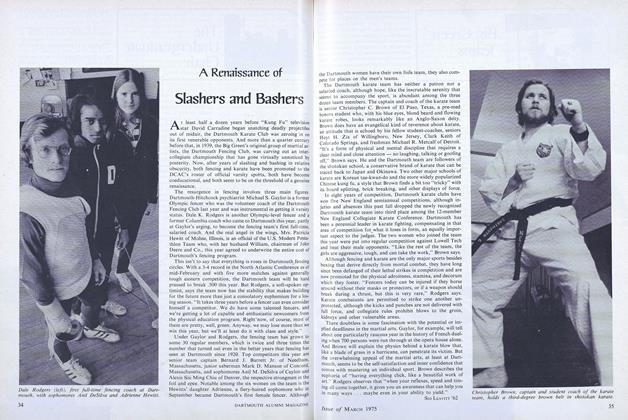

FeatureA Renaissance of Slashers and Bashers

March 1975 By SID LEAVITT '62 -

Feature

FeatureProphet of Limits

NOVEMBER 1993 By Suzanne Spencer '93 -

Feature

FeatureToday: Views of an Embattled Oilman

April 1974 By WILLIAM K.TELL JR.