President Dickey, opening the College's 188 th year,discusses "the place itself" as a pervasiveinfluence on Dartmouth's individuality and character

MEN of the College: I continue to believe that one of the wonderful things about our pattern of higher education is that we face a fresh start each fall. The only more wonderful thing about it, perhaps, is that it always comes to an end each June. However that may be about the end, our thought today is on getting the kind of good start that we're told is half the race in human affairs.

In spirit, at convocation the entire community of the College is met together figuratively to clasp hands in common resolve as we take our assigned positions for another round of give and take in the strenuous business of higher education. In practice, for some years now the limited capacity of Webster Hall has barely accommodated those whose age requires the dignity of. a seat - the seniors, and those whose natural dignity still merits one - the freshmen. This year if all the freshmen were to be seated even the seniors would be crowded out and that, you gentlemen of i960 have already discovered, would be carrying the good thing of a warm welcome too far.

Seated or standing, we extend to the Class of i960 the unqualified welcome: "You are now one of us." Our eyes tell us you are much the biggest class ever to enter Dartmouth and the Admissions Office tells us in your behalf - and incidentally in its defense - that on the records you are also the best. Having now met and matriculated some eight hundred of you in person this past week, I can testify that the late Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia spoke prophetically for our Director of Admissions when he avowed, "I rarely make a mistake but when I do it's a beaut!" May the Class of i960 always be a beautiful best among all the best classes of the Dartmouth fellowship.

The shared thrill of beginning anything important is one o£ those experiences o£ life that is worth making into something a little special. That, I take it, is why we squander champagne on the nose of a new ship as she takes her first plunge and why we celebrate this 188th launching of a new Dartmouth year with the traditional ceremony of convocation.

My aim on these occasions has been to speak on behalf of all of us in reminding each of us of just a few of the things that are ahead, that are here and that are behind in the seemingly eternal enterprise of making better men through education. In years past we have noted qualities of mind and outlook that are certified by experience as necessary ingredients in pro- ducing an uncommonly good and useful man. At best words are only imperfect clues to such things as humility, loyalty, and that synthesis of soul and intellect we call maturity. But it does no harm to acknowledge that all education is largely the art of fashioning and finding imperfect clues. In this respect good education like good poetry is both hard work and good fun.

Dartmouth is committed to the liberating arts as the "best bet" for the liberation of men from both the meagerness and the meanness of mere existence. This sense of purpose to see men made whole in the largest measure makes the liberal arts college different from other educational enterprises, and as with any true purpose it pervades all that we do here. However, I should like now to focus our awareness not on our purposes but on that other most pervasive influence that gives Dartmouth her individuality and character - the place itself.

IT is not necessary to be either a geographer or a sociologist to know that place rubs off on people. And conversely it is not necessary to be a historian to know that over the years the past of an institution becomes as much a part of the place as its physical setting. It is about the place in this full-bodied sense that I speak of Dartmouth to you today.

As I have come to know this College in relation to her sister institutions I have concluded that probably more than any other major American college Dartmouth's character flows from the place and circumstances of her founding. If we would understand our College and her influence on us it is important to remember that the founder of this College deliberately placed it in an outpost position on the northern frontier. And parenthetically it might be remarked that thanks to such history-fashioning influences as the up-and-down geography and climate of these parts and the advice to go west given young men by Horace Greeley, the north country remained an uncrowded frontier until the coming of, not the B & M, but the ski tow.

The frontier location itself assured the College of an adventurous origin and a hard struggle for life, and this influence was compounded by the purpose Wheelock set himself to educate and Christianize the youth of the Indian tribes. Any stranger to Dartmouth's story would need to know only of her frontier founding and of the adversity and dedication attending the early years to make a shrewd guess that here was an institution where early example and continued circumstance would foster an uncommon quality of independence, resourcefulness and fellowship.

Think back to the days of the Dartmouth College Case in 1819 when the College was just approaching its fiftieth year. Was it mere chance that the great issue of independence in the American system between private institutions and the power of the state arose at Dartmouth? And, the issue having been drawn, was it entirely fortuitous that a small, relatively weak outpost college, torn with internal dissension, under great pressure from outside forces and despite defeat in the State Court, still had the determination to carry its cause to the Supreme Court of the United States? Finally, was it purely coincidence that in the court of last resort this issue and this determined small college had a Daniel Webster for their champion? My answer is expressed in the hope that no Dartmouth undergraduate will ever needlessly shortchange his experience here by overlooking the possibility that Daniel Webster prevailed with the court of Mr. Chief Justice Marshall in important part because the motivation and the meaning of this place had rubbed off on him during his student days.

Whatever may be your answer to these questions, there can be no doubting of the fact that the dramatic triumph of Dartmouth's fight for independent life became thereafter an imperishable part of the spirit of the place. People differ in their sensitivity to such influences, but ever since the Dartmouth College Case it has taken a leaden-lined soul (and that kind is never "wholly extinct) to exist here and yet to escape some quickening experience with the idea of independence.

THE achievement of independence is one of the great thresholds of life. For a man or an institution it marks the beginning of nature's most honorable status _ being on your own. But few things are more important today than facing up to the fact that for man and his institutions independence, of itself, is not an ultimate end. It is indeed the threshold to that portion of life where the perplexities, burdens and joys of a fully realized life come in man-sized packages.

We hear much talk these days in international affairs of the need for America to back, even to foster, independence movements in those areas of the world where colonialism has prevailed. Putting aside for an unrealistically easy moment the diplomatic difficulties which such a course presents where we have friends on both sides of the issue, there is not much doubt left in well-informed minds that America, being the place she is, is destined to be at best a bothersome friend of any colonial power and sooner or later the backer of self-determination for all sincere claimants of the right. In a world where such large truths are obscured by both the Kremlin's propaganda and the tactical movements of our own diplomacy there is manifest need for us to be everlastingly about the business of being clear with ourselves and thereby with others as to where we stand on any man s aspiration to independence.

But what is far more critical is for us to be clear with ourselves about the nature of the international community within which national independence can be encouraged and enjoyed.

As a nation we have had almost two hundred years of learning the ways of interdependence after we achieved our independence. Quite a few nations have not yet had ten. We learned our way for the most part in a loosely connected world where national testiness could either be tolerated or cuffed aside without the risk of catastrophe for civilization. Nations born in the shadow of man-made mushroom clouds come into a very different kind of world, and being late to cross the threshold into political and economic independence, they are naturally enough in a fretful hurry, terribly preoccupied with what they want and not inclined to be very deferential to their elders in their community relations. Such nations are rarely going to be led by men of moderation. To put it very mildly, moderation is more appealing as a political platform from Maine to California than from Morocco to Singapore. And worst of all, perhaps, the new nations of this day come into a riven world community where the older nations are divided in a struggle which at best invites exploitation by the newcomers and too often sets a dangerously bad example for them.

The ills that flow from such a brew cannot be prescribed for on this occasion, but there can be no harm in asking ourselves a few of the questions that frame our outlook on troubles such as those that now focus on Egypt and the international interests at issue in the Suez crisis.

Do we really believe with our President that short of replying to armed aggression there is no alternative for us but peace? If we do, is there any alternative for dealing with the abuses of independence except a more perfect community of the nations? If so, are we prepared to take our chances with such a community when the focus of the issue shifts to the Dardanelles, the Straits of Gibraltar, even the Panama Canal? Do we continue to regard the veto provisions of the United Nations Charter as being practically and morally compatible with the fashioning of such a more perfect international community? If not, are we prepared to lead the way in expanding a veto-free organization such as NATO into a sufficiently comprehensive enterprise either hopefully to gird the moral sanction of a developing UN Assembly with durable deterrent force, pending true disarmament, or, at second best, to provide like-minded nations with an alternative to the UN around which to build the structure of their community in the unhappy event the UN with its vetolocked amendment procedure should prove to have exhausted its ability to grow and evolve? And there will long be the question, after all we've spent and the trouble we've seen, are we prepared indefinitely to invest the patience, the effort and the money that goes into binding together any community with a sense of self-interest in shared well-being?

These are large and hard questions and in the main they are too unlimited to be posed, let alone answered, by statemen in office. But let us not delude ourselves into believing that such questions do not exist simply because they are not asked. They are the inevitable companions of the idea of independence in an expanding world of nation states.

MANY explanations have been suggested for the dynamic quality of the strength that has characterized American life, but if I had to single out the essence of our talent for getting things done I think I should rest my case on our unique capacity for combining within our institutions and our undertakings both an instinct for independence and a sense of community. May it not be that this complementary combination is the true genius of America and that properly understood it is the most valuable export we have left to offer a world where freedom and authority, in whatever form, have never yet for long made a go of it alone?

There are few, if any, really great ideas, gentlemen, that are not grounded in the common experience of individual men. The American idea of the possible oneness of independence and community is your heritage in this place. The years of Dartmouth life are dominated at every point with the achievement of your own independence while coming to at least tentative terms with one community after another. Whether it be in the dormitory or the fraternity, in the classroom or on the playing field, in the government of the College or the affairs of nations, or in your relationship to that largest community of all - the universe, Dartmouth is where you will cross the threshold of independence to something larger.

And now, men of Dartmouth, as I have said on this occasion before, as members of the College you have three different but closely intertwined roles to play:

First, you are citizens of a community and are expected to act as such.

Second, you are the stuff of an institution and what you are it will be.

Thirdly, your business here is learning and that is up to you.

We'll be with you all the way, and Good Luck!

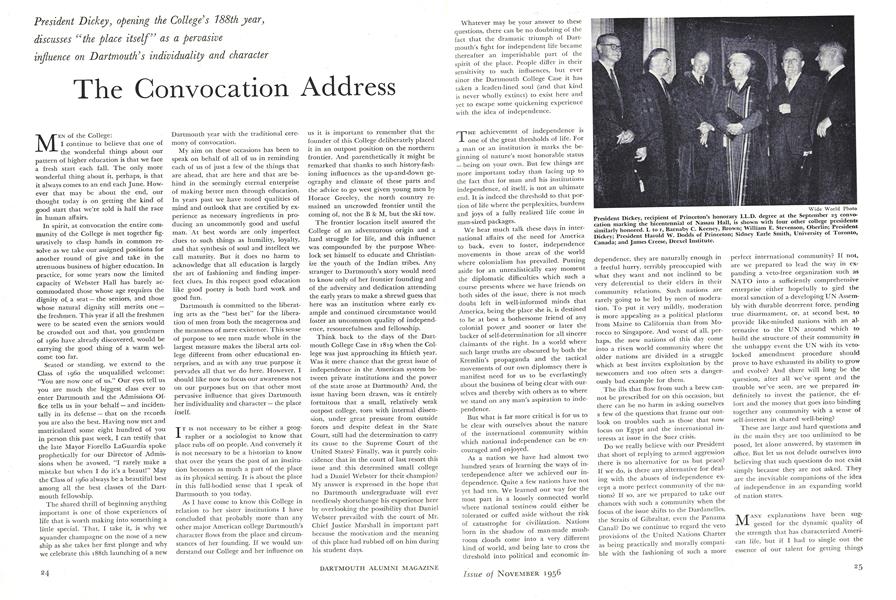

President Dickey, recipient of Princeton's honorary LL.D. degree at the September 23 convocation marking the bicentennial of Nassau Hall, is shown with four other college presidents similarly honored. L to r, Barnaby C. Keeney, Brown; William E Stevenson, Oberlin; President Dickey; President Harold W. Dodds of Princeton; Sidney Earle Smith, University of Toronto, Canada; and James Creese, Drexel Institute.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Poet as Teacher The Poet as Teacher

November 1956 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Feature

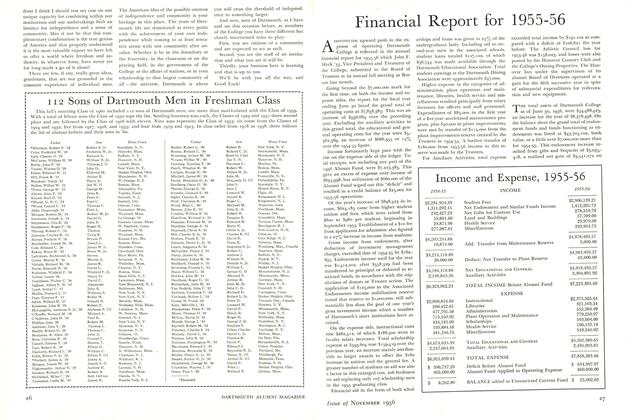

FeatureFinancial Report for 1955-56

November 1956 -

Feature

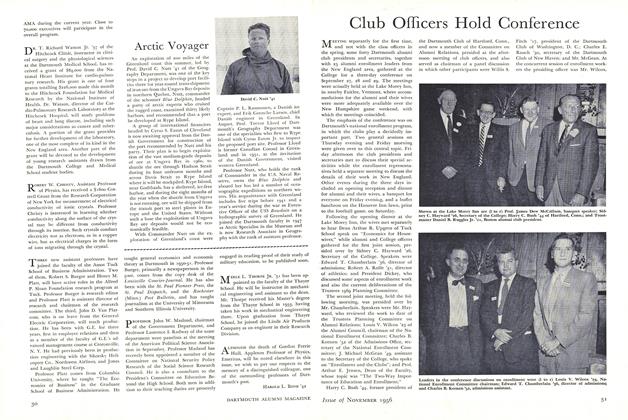

FeatureClub Officers Hold Conference

November 1956 -

Class Notes

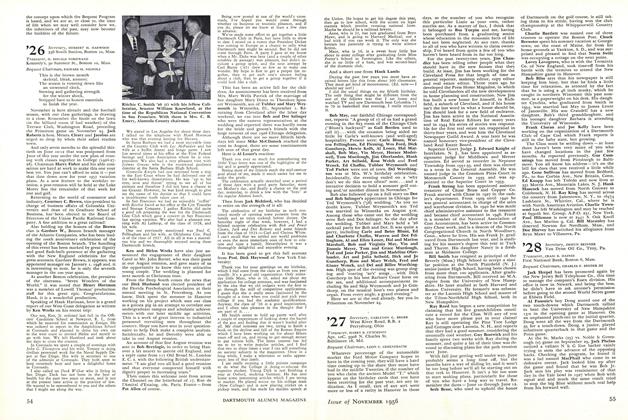

Class Notes1926

November 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

November 1956 By RICHARD C. CAHN, FDWARD F. BOYLE, RICHARD CALKINS

Features

-

FEATURES

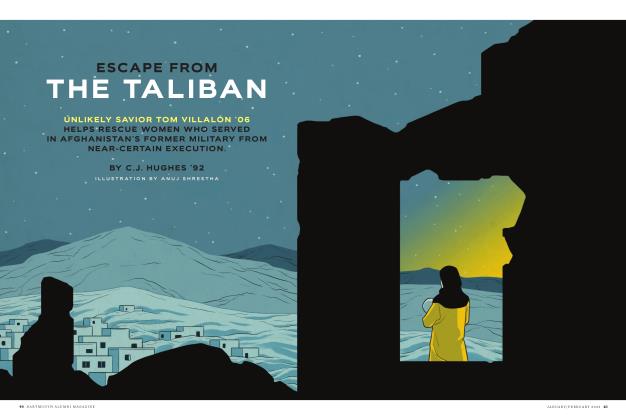

FEATURESEscape From the Taliban

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2023 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

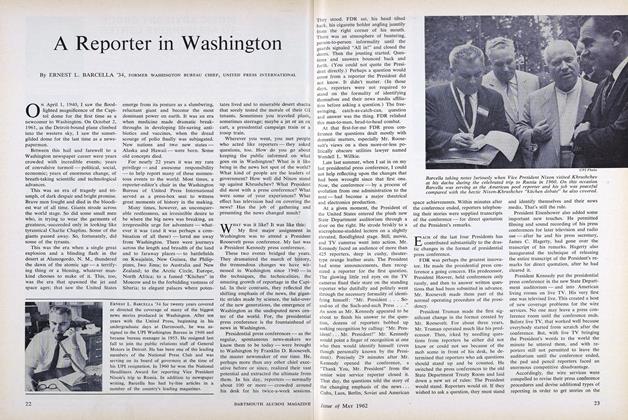

FeatureA Reporter in Washington

May 1962 By ERNEST L. BARCELLA '34 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO LIVE A MORE MEANINGFUL LIFE AND DIE HAPPY

Jan/Feb 2009 By KUL GAUTAM '72 -

Feature

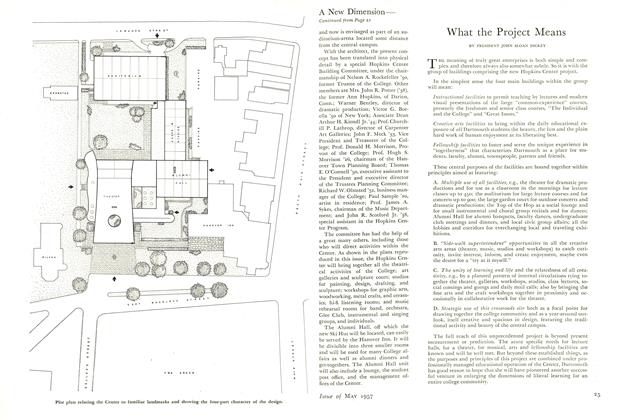

FeatureWhat the Project Means

MAY 1957 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Beat of Terror

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By STUART A. REID ’08 -

Feature

FeatureThe Arts in Our Colleges

JANUARY 1963 By WILLIAM SCHUMAN, L.H.D. '62