Today's ecologists focus on overpopulation as the key to understanding the environmental crisis. In the voluminous literature on the subject, much is being written from a neo-Malthusian point of view, but almost completely unexamined is the Marxian view that the population problem is rooted in social and economic exploitation. I want to argue that a synthesis of the neo-Malthusian and Marxist views brings us closer to the core of the problem.

Current concern for overpopulation of the world environment is a new revival of the Malthusian spirit. The population alarmists, led by Paul Ehrlich, feel that the growing population of the world is over-extending the "carrying capacity" of the earth—the land's ability to support life. Vital resources and food production potentials are being exhausted in the face of the expanding millions of people. Overpopulation causes the social problems of poverty, pollution, riots, crime, alienation, racism, and unemployment.

This argument was the one used by Thomas Malthus, the "father" of modern population study, in 1798 when he wrote An Essay on the Principle ofPopulation as It Affects the FutureImprovement of Society. With regard to Britain in the early 1780's, Malthus wrote, "The poverty and misery arising from a too rapid increase of population had been directly seen, and the most violent remedies proposed so long ago as the times of Plato and Aristotle."

For Malthus, population will always grow and poverty in Britain will always exist. This argument was used to discontinue the British Poor Laws and therefore to justify a conservative social order. Malthus himself was not concerned with the control of population.

Today, the neo-Malthusians have resurrected this argument to place the burden of war, poverty, and pollution on excessive population growth. They relate the backwardness of underdeveloped countries to unchecked fertility, and argue that unless population growth is stopped there can be no economic development for the "teeming millions."

The neo-Malthusians go beyond Malthus in that they have a genuine concern for the poor and feel there is a solution to the problem. Yet since they define the root of the poverty-pollution problems to be on the population level, they argue that the ultimate solution must be a lowering of population growth and not social justice. The result is a conservatism much like that of Mai thus.

Accordingly, William Vogt, in Roadto Survival, says that the United States should not give aid to underdeveloped countries without provisions for the limitation of their populations. The Malthusian Theory states that population grows "naturally" faster than food production and will outstrip the means of subsistence. The population and means-of-subsistence curves have crossed and are out of control. From this population theory comes Ehrlich's policy solution: a drastic curb in the population by enforced sterilization or by increasing taxes on large families.

I want to argue that the alarmist point of view fails to consider the dependence of overpopulation upon the economic, social, and political factors of society. Secondly, the Marxist critique of overpopulation puts the neo-Malthusian interpretation in perspective and broadens the nature of the population problem to include the issue of economic and social justice.

Marx would say that the exploitative social and economic arrangements of capitalism are the cause of overpopulation, pollution, and poverty. That ghetto conditions are caused by overpopulation is hard to believe when the population density is ten times greater in the United Kingdom than in the United States, and thirty times greater in the Netherlands. Today, the fertility of the environment is decreasing because the economic and social structures are based on exploitation and encourage squandering of resources. Our petroleum resources in Alaska are endangered because developers desire short-term profits despite the known ecological damage and the fact that oil is man's only lubricant for which there is no substitute. The exploitative, puritan values needed to maintain the system are rooted deep in the fabric of our culture. The neo-Malthusians cover up the social roots of the problem by blaming "man's nature" or "technology" rather than capitalism.

Marx wrote, "Of course, it is far more convenient, and much more in conformity with the interests of the ruling class... to explain... 'overpopulation' by the eternal laws of Nature, rather than the historical laws of capitalist production."

Capitalism, in Marx's view, promotes a surplus population in order to have a reserve army of labor - a labor pool to compete and drive down wages. The Keynesian values of growth and economic expansion to prevent boom and bust cycles demand new markets and accumulated capital for investment.

"But if a surplus labouring population is a necessary product of accumulation or of the development of wealth on a capitalist basis this surplus-population becomes, conversely, the lever of capitalist accumulation, a condition of existence of the capitalist mode of production. Independently of the limits of the actual increase of population, it creates, for the changing needs of the self-expansion of capitalism, a mass of human material always ready for exploitation." (Marx quoted in Meek, Marx and Engels on Malthus.)

A brief look at the population issue with regard to Japan, Dutch Indonesia, American women, and USA population policy toward the Third World will serve to illustrate the Marxist position.

Japan cut its birth rate in half in ten years by an extensive education program through the media, creating economic incentives for small families, and a national Eugenic Protection Law of 1948 that legalized abortion. Then, last summer Prime Minister Sato announced a policy desire to increase the population birth rate because industry is seeking cheap labor. A shortage of labor threatens to undermine Japan's economic progress.

A demographic study of Dutch Indonesia, in Clifford Geertz's Agricultural Involution, contends that overpopulation in a colonial country is the result of colonialism. With a decreasing mortality rate the Dutch deliberately encouraged population growth to gain an increased labor force. A law made the Indonesian population pay taxes not in money but in labor.

The desire for a surplus population is also demonstrated by the secondary role women play in our society: exploited laborer and breeder. Women are a crucial factor in the capitalist exploitation of the working class, for they provide a flexible reserve supply of labor. Denied equal opportunity in labor participation, women are moved easily in and out of the labor force in times of crisis such as World War II.

"Equal opportunity for women could raise our labor costs, make it hard for us to adjust supply to demand, and reduce the flexibility of our economy." (Bird, Born Female.)

The ideology of male chauvinism, the idea that men are innately superior to women, is used to justify differential treatment toward women. Women are channeled into menial work, excluded from other jobs, and paid less for equivalent work. In Boston in 1968 the average wage for the identical job description of "accounting clerk" was $126 a week for men and $107 a week for women. As exploited workers women provide capitalism with the lowcost labor it demands. The political economy of male chauvinism is both powerful and profitable.

Finally, we turn to U. S. population policy toward Third World nations. It is not a combined effort of economic and social aid to help the neo-colonial countries develop into independent economic entities. Nor is it complete disregard for 'source countries' who provide raw materials and profits for monoply capitalism because of the threat the strength of 'unchecked' numbers pose to the security of capitalism. The United States with only six percent of the world's population controls sixty percent of the world's resources. With a genuine commitment to the poor and population tagged as the source of underdevelopment the American government endorses population control as the primary remedy. Yet policy-makers cannot understand the cries of "genocide" from the Third World peoples. The poor do not trust the rich man's concern for their "welfare" because they see nothing but social and economic injustice around them. Numbers is their only power.

In The Population Bomb, Paul Erlich writes: "We are going to be sitting on top of the only food surpluses available for distribution, and those surpluses will not be large. In addition, it is not unreasonable to expect our level of affluence to continue to increase over the next few years as the situation in the rest of the world grows even more desperate. Can we guess what effect this growing disparity will have on our 'shipmates' in the under-developed countries? Will they starve gracefully, without rocking the boat, or will they attempt to overwhelm us in order to get what they consider to be their fair share?"

Marx declared that the next stage in the development of the historical dialectic would be a socialist society where overpopulation would not be a problem because society would emphasize every individual's needs rather than the profits of the capitalists. It was his view that social justice will accrue to the individual when the ruling class is replaced by the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Today, no matter what the economic system, whether a form of capitalism or socialism, there is a severe population problem. The alarmists place the guilt solely on exponential population growth, and demand that it be curbed by any means. The Marxist critique exposes a real thread that runs through-out capitalism: the desire for a reserve army of labor to hold down wages. The fundamental Marxist truth that "all labor is intrinsically equal because it is human labor" reminds us that the basic ethical goal of any economic system is to diminish the inequalities of the social structure of society.

Neither solution alone provides a full answer to the problem. It has been my purpose here to argue for a synthesis, because the Marxian view of the social and economic roots of overpopulation, hitherto largely ignored, can add to our understanding of the problem. This is especially so with relation to the status of women, for if the economic and social arrangements of our time encouraged women to enter the labor force without discrimination, the population growth rate would decrease as a result of delayed marriages and fewer child-bearing years. The problem of overpopulation cannot be separated from the broader issue of economic and social justice.

Charles Collier '7l of Wellesley, Mass.,is majoring in religion and will enter Harvard Divinity School in the fall. His deepinterest in environmental problems led himto serve as an intern with the VermontEnvironmental Center in Ripton, Vt., lastsummer and to assist in collecting theenvironmental articles for this issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMan and His Environment

June 1971 By ALVIN O. CONVERSE -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1971 By B.B. -

Feature

FeatureWhat Price Clean Air?

June 1971 By Robert B. Graham '40 -

Feature

FeatureTeaching at a Communist University

June 1971 By NOEL PERRIN -

Article

ArticleA Second Life Through Heart Surgery

June 1971 By Daniel L. Dyer '39 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1971 By JOHN H. MARSHALL '71

Charles W. Collier '71

Features

-

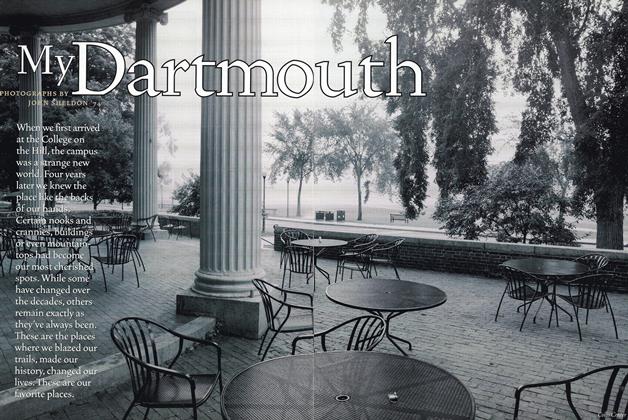

Cover Story

Cover StoryFavorite Places

Mar/Apr 2002 -

Feature

FeatureThe Diminishing Citizen

July 1962 By BASIL O'CONNOR '12 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBlack Dan's Reunion

June 1989 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

MARCH 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureBards in a Barren Desert

November 1982 By Stephen Geller '62 -

FEATURE

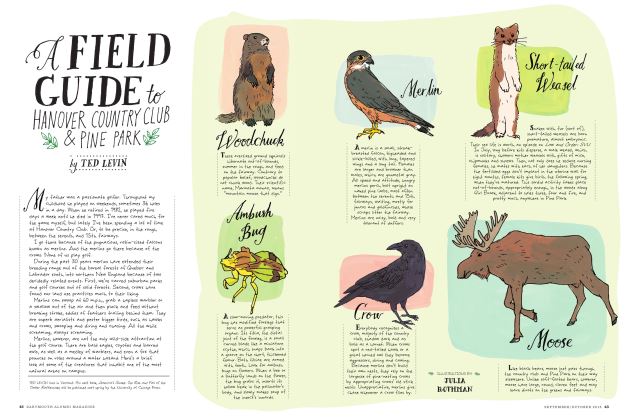

FEATUREA Field Guide to Hanover Country Club & Pine Park

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By TED LEVIN