It was late afternoon on New Year's Day, 1889, when Richard Hovey found himself the sole passenger in a railroad car headed south towards Bloomington, Ind. He was returning to his birthplace after a few years on his own, and as the setting sun touched the horizon, the 24-year-old Hovey was smitten by the power of the moment and decided upon his vocation. He would be a man of letters, and his masterwork, already forming in his mind, would be a series of nine plays which together would constitute a great dramatic poem. The subject would be the story of Launcelot and Guenevere, and the work would offer nothing less than a new moral code for modern society.

Given a purpose so noble and a scheme so grand, not to mention poetic skills which came to be admired by both American and British reviewers, Hovey might have created one of the first Arthurian works by an American writer. By the time of his death only 11 years later, however, the masterwork was only about half completed. And Hovey himself, when remembered at all in literary histories, is mentioned only as one of the selfstyled "vagabond poets" of the 1890s. Lyrics of good fellowship and life on the open road were his most popular contributions to the literature of the day. The four plays in the Launcelot andGuenevere series that were published before his death enjoyed a modest popularity for a few more years and then were all but forgotten.

Hovey was a striking public figure in his time, a handsome young man with a Dartmouth education (class of 1885) and aristocratic connections which assisted his rise to a level of moderate literary prominence. A touch of scandal and unconventional behavior enhances his reputation, and indeed some of the darker, more romantic aspects of his life strike one as almost Byronic. Most notable was the affair between Hovey and Henrietta Russell, the wife of a well-known spokesman for Delsartism, a system of breathing exercises then in vogue among the eastern upper class.

Henrietta Russell was an extraordinary woman in her own right. A flamboyant public figure some 14 years older than Hovey, she moved with grace and authority among the matrons of Newport, conducting Delsartism sessions of her own, lecturing, and writing a book. When one learns that Hovey had intended Launcelot andGuenevere to illustrate the "higher morality" achievable in an illicit love affair, it is all too easy to see Hovey's Arthurian project as an apologia for the great romance of his own life. A biographer, Allan Macdonald, has pointed out that Hovey did not meet Mrs. Russell until after the project was planned, but the fact remains that for several years the poet was in a Launcelot-like situation. Henrietta was eventually to travel to Europe with Hovey, to bear his child, later divorce her husband, and finally, in 1894, to marry Hovey. If his Arthurian plays were intended to justify their affair, then one hopes that Henrietta's own book drew all of its material from her breathing exercises and none from their relationship. The book's title was Yawning.

It is thanks to Henrietta Hovey that we have the poet's design for the entire cycle of plays, collectively and somewhat confusingly entitled Launcelot andGuenevere: A Poem in Dramas. In 1907 she published the fragments of the fifth play, The Holy Graal, as well as notes left by Hovey and scraps of dialogue and verse intended for later works in the series. The cycle of plays was to be structured in three parts, with each part consisting of a masque, an unresolved tragedy, and a third drama which would provide a "reconciliation and solution." In Part I, Launcelot and Guenevere would attempt to keep their relationship above the responsibilities required by their social positions. Part II, of which only the opening masque was completed, was to show their attempt to set social duty above their love for each other. The final resolution of these opposing courses would occur, in a manner not quite clear, in Part III, to end with a "harmonody" entitled Avalon.

The first two plays were established together in 1891. In the masque entitled The Quest of Merlin, the wizard seeks knowledge of the outcome of the queen's love affair. More spectacle than drama, the play features encounters between Merlin and the Norns and Valkyrs of northern mythology, Greek gods, fairy queens, and sundry other creatures of fable.

The Marriage of Guenevere is a much more conventional play. Guenevere is introduced at that point where she must set aside her feminist tendencies and marry Arthur out of duty to the country. She immediately falls in love with Launcelot, however, and they both recognize in their passionate relationship a marriage of a higher order than that which binds her to the king. After some intrigue, the play concludes with the magnanimous Arthur dismissing the charges brought against the lovers.

The third play in the series was not published until 1898. The Birth of Galahad continues the story from the preceding play. With Arthur and Launcelot off to war against Rome, Guenevere, in a rather original Hovey twist, gives, birth to Launcelot's son, Galahad. With Merlin's help, the child is given to a young widow to raise. The secret falls into the hands of Lucius, the Roman emperor, whose blackmail attempt is thwarted and the secret preserved when he is pitched from a balcony by Launcelot. The death of Lucius also provides Arthur the opportunity of ascending the throne of Rome.

Taliesin: A Masque, intended to serve as the prelude to Part II, actually reached print in Poet-Lore a periodical featuring popular verse, during 1896, some three years before it was published in book form. Considered the best of Hovey's poetic dramas, it features the knight Percival and the bard Taliesin at the threshold of their careers. Among the splendors of this masque are such settings as the forest of Broceliande, Mount Helicon, and the Graal Chapel. The play also provides a visit with the slumbering Merlin, a naked Nimue, a dance of the Muses, and a conversation with the seven angels who see God continually. Hovey noted that this play, in which Taliesin and Percival glimpse their destinies, was to suggest "the aesthetic drift of the poem."

The fragmentary The Holy Graal, unpublished until 1907, was to show the coming of the grown Galahad to court, the failures of the Graal knights, the broken spirit of Launcelot, and Galahad's achievement of the Quest. A subplot involved the death of the scheming Morgause and her lover Lamoracke at the hands of Gawain. Only a few scenes were completed, however. Even less exists of Astolat: AnIdyllic Drama, which was to conclude Part II. The notes indicate that the play would have explored the effects of jealousy and end with the death of Elaine and the reconciliation of Launcelot and Guenevere. Tristan and Iseult would have provided a subplot.

The final three plays also exist only in bits of dialogue, list of characters, and sketchy notes, but these are sufficient to suggest the poet's intended conclusion to the cycle. Fata Morgana:A Masque was to be as bizarre in characters and settings as the opening plays in Parts I and II. Hindu, Persian, and Hellenic ethical concepts were to be featured, as well as a descent into Hell to visit Lucifer. The next play, King Arthur: A Tragedy, would tell the traditional story of the condemnation of Guenevere, her rescue by Launcelot, the siege of Joyous Gard, Modred's treachery, and Arthur's death. Avalon:A Harmonody was to provide a final reconciliation of "Religion, State, Society, Family, and Individual" in Hovey's words. Precisely how the lovers' affair was to be resolved in unknown. It seems certain, however, that in the setting of Avalon, Launcelot and Guenevere's bond would emerge as a marriage transcending earthly social codes and the legal bonds between the queen and Arthur.

The Arthurian plays have little to recommend them to modern readers. Although Hovey was a poet of considerable prosodic skills, he learned his playwriting from Shakespeare, who furnished Hovey more images, characters, situations, and words than his gifts could handle. The plays are, quite simply, period pieces.

Hovey was still being spoken of as a poet of promise when he died a less than Byronic death, of complications following testicle surgery, at the age of 35. American reviewers were kinder to him than those in England, but his skills were admired on both sides. Arthurian material appeared in Hovey's lyric poems as well as in his plays. An early sonnet, written the year before his epiphany on the train, shows both his interest in the characters and a viewpoint on relationships which charmed many readers of his day.

LAUNCELOT AND GAWAINE A poet loved two women. One was dark, Luxuriant with the beauty of the south, A heart of fire; and this one he forsook. The other slender, fair, with wide grey eyes, Who loved him with a still intensity That made her heart a shrine; to her he clave, And he was faithful to her to the end. And when the poet died, a song was found Which he had writ of Launcelot and Gawaine; And when the women read it, one cried out: "Where got he Launcelot? Gawaine I know He drew that picture from a looking-glass! Sleek, lying, treacherous, golden-tongued Gawaine!" The other, smiling, murmured, "Launcelot!"

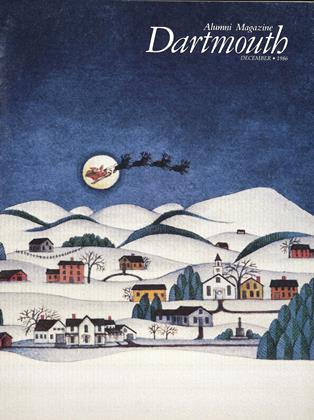

Hovey's love of theater was evident in college, as when he played Bunthorne in Gilbert and Sullivan's Patience in 1885.

TDP I tl/JLJ ~sr OT3 71 AT AND OTHER FRAGMENTS BY RiCfcARD &OVEY BEING THE UNCOMPLETED PARTS OF THE ARTHURIAN DRAMAS Edited <with Introduction and Notes by MRS. RICHARD HOVEY And a Preface by BLISS CARMAN NEW YORK DUFFIELD & COMPANY 1907

The author is a collector of Arthurian workswith a special interest in those producedafter the Middle Ages. He is also a memberof the editorial staff of Avalon to Camelot, a publication devoted to Arthurian matters.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIn Pursuit of a Pediatrician

December 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeatureLawyers, Liberal Arts, and the Cold War

December 1986 By Weyman I. Lundquist '52 -

Feature

FeatureSnowmaking at the Dartmouth Skiway: Taking the Wonder Out of Winter

December 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleMarianne Alverson: At home in many worlds

December 1986 By Lee McDavid -

Article

ArticleHarold Sack '32: A master of pieces of the past

December 1986 By Rex Roberts -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

December 1986 By C. E. Widmayer

Features

-

Feature

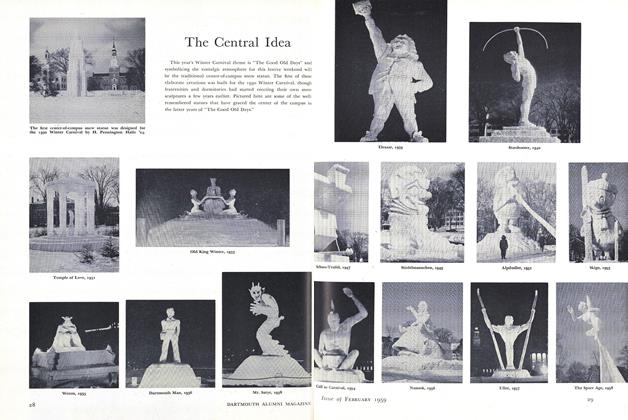

FeatureThe Central Idea

FEBRUARY 1959 -

Feature

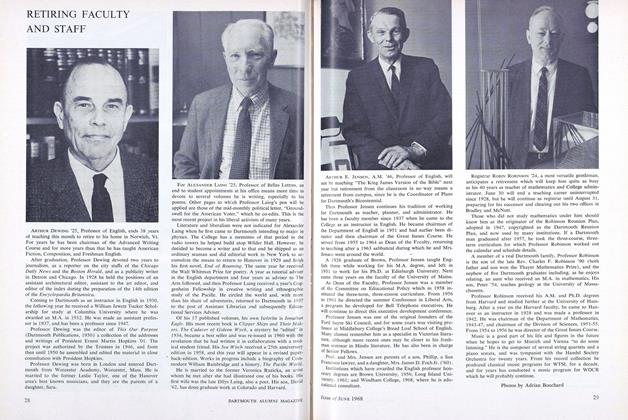

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY AND STAFF

JUNE 1968 -

Feature

FeatureArt Carpenter

APRIL 1973 -

Feature

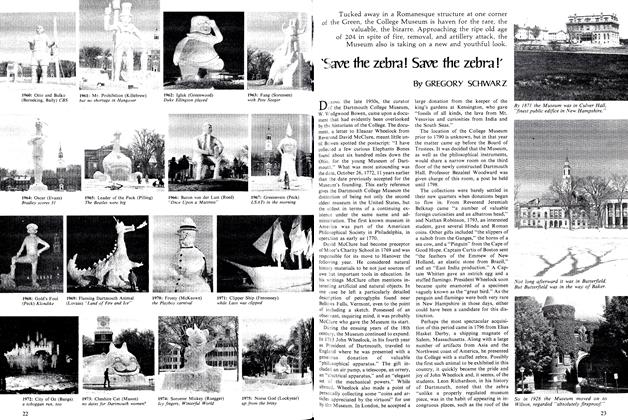

Feature'Save the zebra! Save the zebra!'

February 1976 By GREGORY SCHWARZ -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCanned Lit

MARCH 1995 By Maury Rapf '35 -

Feature

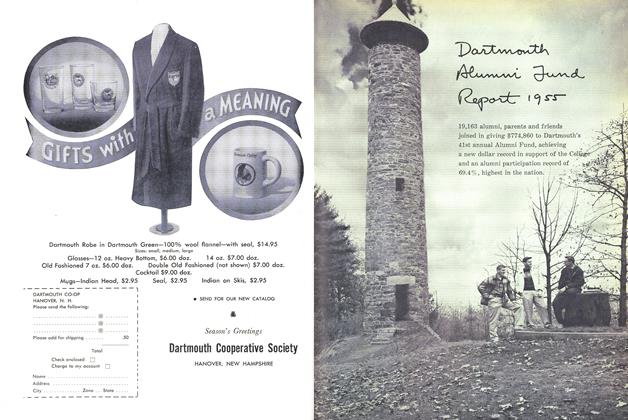

FeatureChairman's Report THE 1955 ALUMNI FUND

December 1955 By Roger C. Wilde '21