By Howard A. Bradley andJames A. Winans. Columbia, Missouri: Artcraft Press, 1956. 230 pp. $3.00.

The murder of Captain Joseph White in Salem, Massachusetts, in April 1830 and the evidence introduced in the trials that followed give emphasis to the adage that "truth is stranger than fiction."

Although not a detective story but a scholarly investigation of the events surrounding the murder and the part Daniel Webster played in the trials, this volume lays bare many aspects of a fascinating case including the important evidence, portions of the summation speeches, and Webster's reconstruction of his words in the trial of Frank Knapp. What would you like in a case? A conspiracy, the arrest of innocent persons, a genuine and a fake robbery, mysterious men on a dark street, confessions, alibis, an ex-convict and blackmailer as a chief witness, a suicide - all these are here. Moreover, the authors issue a challenge: study the evidence, read the speeches and decide "whether a given argument has a sound basis of testimony back of it, or whether the evidence is distorted or overvalued." It is their purpose "to give a clear picture of the case without prejudice."

The eighty-two-year-old victim was killed while asleep by a blow on the head with a club, specially turned for the purpose by the assassin, and by thirteen stab wounds, some of which penetrated the heart. Massachusetts was so incensed by this brutal crime that the Supreme Judicial Court was called into session by a special act of the legislature. When the supposed assassin, Richard Crowninshield, committed suicide, the Commonwealth apparently was left without a principal. The government turned to Daniel Webster for help. Webster thus became the chief counsel for the prosecution, and there seems to be no question that his brilliant efforts in the trials of Frank and Joseph Knapp resulted in their conviction and death by hanging.

Here are some other facets of the book. Webster's "purple passages" which schoolboys used to recite with gusto did not hang Frank Knapp because that speech was delivered at the first trial in which the jury disagreed. There is a copy of a receipt for $1,000 signed by Webster, although he denied he had received any fee when the question was raised in court. Lawyers will wish to scrutinize the evidence of the Reverend Colman and Webster's argument to the court on the admissibility of Frank's "confession." Above all, in the eyes of this, reviewer, the book poses the disturbing question: Is this, perhaps, a perfect example of a case where the defendants are morally but not legally guilty?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

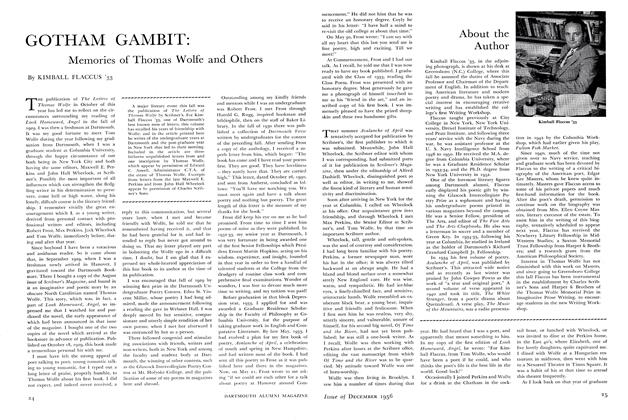

FeatureGOTHAM GAMBIT:

December 1956 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Feature

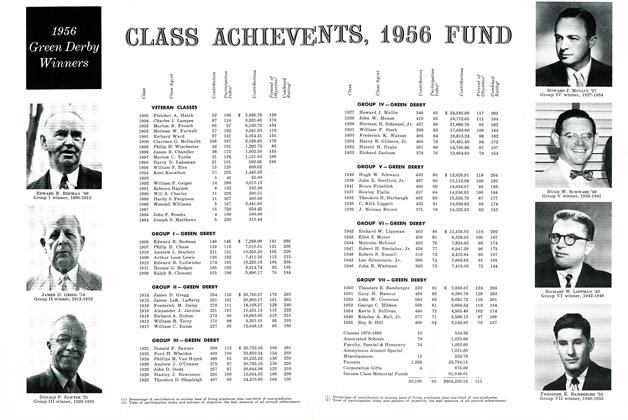

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVENTS, 1956 FUND

December 1956 -

Feature

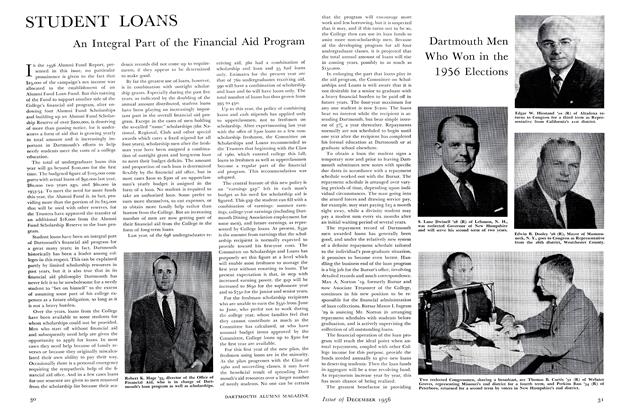

FeatureSTUDENT LOANS

December 1956 -

Feature

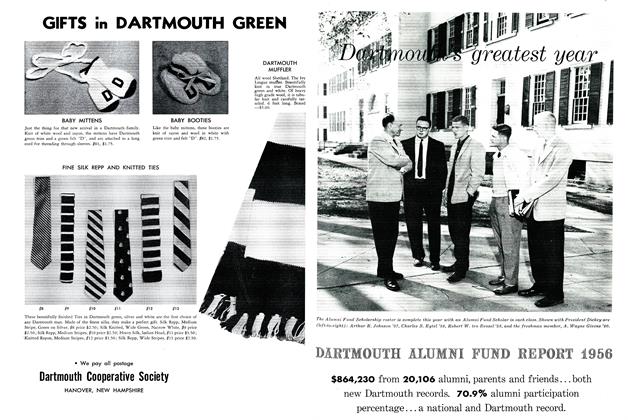

FeatureTHE 1956 ALUMNI FUND

December 1956 By William G. Morton '28 -

Feature

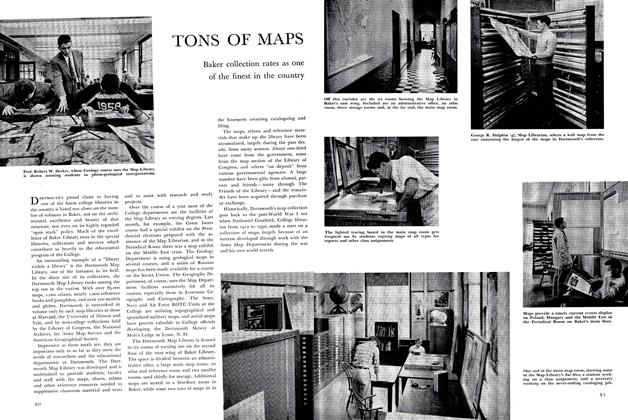

FeatureTONS OF MAPS

December 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

December 1956 By RICHARD C. CAHN, LT. (JG) EDWARD F. BOYLE, RICHARD CALKINS

Books

-

Books

BooksFIFTY SIX DARTMOUTH POEMS.

MAY 1972 By DOROTHY BECK -

Books

BooksTHE LATE GREAT CREATURE.

APRIL 1972 By J. DONALD O'HARA '53 -

Books

BooksMICROSCOPIC IDENTIFICATION OF CRYSTALS.

JULY 1972 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY JR. '63 -

Books

BooksTHERMOSTATICS AND THERMODYNAMICS.

February 1962 By JOSEPH J. ERMENC -

Books

BooksTHE COMPLETE COOKBOOK FOR MEN.

April 1962 By SUE TRIBUS -

Books

BooksA SHORT HISTORY OF AMERICAN LIFE.

October 1952 By W. R. Waterman