PAGE 2, THE BEST OF "SPEAKING OF BOOKS" FROM THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW.

FEBRUARY 1969 JOHN HURD '21PAGE 2, THE BEST OF "SPEAKING OF BOOKS" FROM THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW. JOHN HURD '21 FEBRUARY 1969

Edited and with an introduction by Francis Brown '25.New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston,A New York Times Book, 1969. 300 pp.$6.95.

Not many years ago it was a cliche: Americans were too hurried, too dramatic, not to say hysterical, to write essays. Stylistically controlled, devoted to humorous understatement, conservatively personal, the British were the only ones who could. American academicians used to shake their heads at their fellow-countrymen's inability to write well. One had only to read the TimesLiterary Supplement to recognize how superior it was to any American magazine or newspaper.

Francis Brown's book is proof that times have changed. One hears now at coffee breaks how self-consciously erudite are the TLS's leading and unsigned essays, and how dull. The personal charm is labored. The silvery sentence is tarnished. If not rancid, the oil in the lamp is not pellucidly fresh.

Page 2 should be Page 1 news in England. The New York Times Book Review essays are truly remarkable in their range and depth, subtlety and insights, humor and charm. One needs a new definition of the essay; the old will not do. "A literary composition, analytical or interpretative, dealing with its subject from a more or less limited or personal standpoint." That is from Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary, 1953 edition.

Page 2 consists of seven main sections. Saul Bellow in "The Literary Scene" discusses Cloister Culture. ("It is in the universities that literary intellectuals are made, not on Grub Street, nor in Bohemia.") In "The Writer's Occupation" George P. Elliott holds forth about writers on campus of which he is one. ("American universities haven't been ivory towers for a generation.") In "The Novelist as Hero," Alex Waugh, who has been writing for 50 years, remarks that he is most alive when seated in a hotel room facing a solitary day. In "On Style and Styles" Eric Partridge, who in his Oxford oral examination was chided for using a slang term and two colloquialisms, observes that "for the lazy, the lethargic, the envious, Bedlam is as musical as Bach or Beethoven or Brahms; an indolent insolent daub is foisted on us as an example of genius." In "Visitations" Carlos Baker '32, Woodrow Wilson Professor of Literature at Princeton, comments on what Italy meant to Ernest Hemingway, and in "The Experience of Literature" he holds forth on the New Critics, now obsolescent, the relevance of biographical knowledge, and Leslie Fiedler's whipping of the anti-biographers. In "Portraits, Appraisals and Reappraisals," Francis Steegmuller '27 reminisces about Guillaume Apollinaire, Jacqueline (his pretty redhead), Picasso, Cocteau, and Andre Salmon.

The richness and variety of this book may be suggested by the simple fact that 62 authors are presented because they can write well and entertainingly about what fascinates them. Charming chaos? "The fagade of casualness misleads," as Mr. Brown remarks. The essays emerge from a planned planlessness into some sort of order be- cause the writers, freed from dictation, editorial schemes, and matters of style, could concentrate on their own selves in autobiography to be defined as "all of which I saw, and some of which I was."

And so with such rich diversity emerges a pattern sophisticatedly engineered. Mr. grown puts it succinctly, "The order of the collection... is a procession moving from the general to the specific, playing with literary ideas and concepts as it goes along, saluting accomplishment, making room for experience."

The book on your living-room table will become a conversation piece. Read it, and you may become one also.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

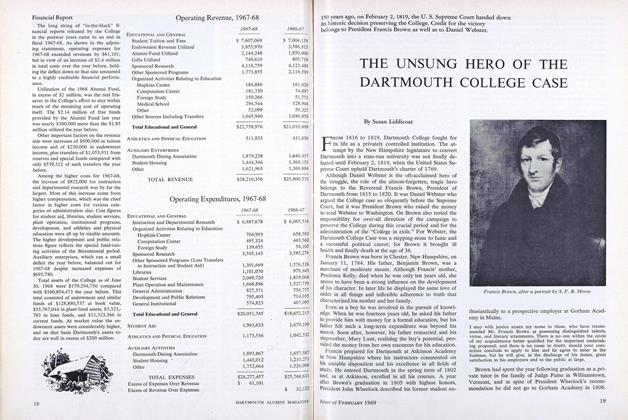

FeatureTHE UNSUNG HERO OF THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE

February 1969 By Susan Liddicoat -

Feature

FeatureThe Bearing of the Green

February 1969 By Mary B. Ross ('38) -

Feature

FeatureA Call for Equal Opportunity

February 1969 -

Feature

FeatureA Student View of the Crisis, 1816-19

February 1969 -

Article

ArticleTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

ArticleHanover's First Aid Maestro

December 1942 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksHOW TO LIVE LIKE A RETIRED MILLIONAIRE ON LESS THAN $250 A MONTH.

November 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksLAUGHTER AND TEARS.

FEBRUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksEIGHTEENTH CENTURY STUDIES PRESENTED TO ARTHUR M. WILSON.

NOVEMBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksAMAZING BUT TRUE: STORIES ABOUT PEOPLE, PLACES, AND THINGS.

MAY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksQUICK GUIDE TO CHEESE. HOW TO BUY CHEESE HOW TO KEEP CHEESE HOW TO SERVE CHEESE HOW TO SELECT CHEESE.

November 1973 By John Hurd '21

Books

-

Books

BooksATTENTION ALUMNI

MARCH 1930 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Nov/Dec 2004 -

Books

BooksWHO'S WHO AMONG THE MICROBES

MARCH 1930 By A. H. Chivers -

Books

BooksEUGEN ROSENSTOCK-HUESSY: BIBLIOGRAPHY-BIOGRAPHY.

December 1959 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksBut No B-52's

October 1975 By JOHNHURD '21 -

Books

BooksThe City Manager.

FEBRUARY, 1928 By W. A. R.