Letters to the editor in this issue indicatethat the relation of the new HopkinsCenter to Dartmouth Row is a question ofreal concern to some alumni. At the Junemeeting of the Dartmouth Alumni Council,Professor Lathrop gave an interestingand enlightening talk on this and otheraspects of the Hopkins Center. The talk,as tape recorded, is printed here in full.

PROFESSOR OF ART

I'VE been asked to speak first about the orientation and placing of the various activities within the Hopkins Center, and then to talk about the architecture o£ the building itself and the relation of the building to the campus, particularly the relation to the existing buildings around the green.

Remember that the Hopkins Center is bringing together activities of all the arts and crafts with activities of a social, recreational or instructional nature. It houses these multiple activities in space which is the equivalent of four or five conventional buildings. It is a group of buildings, like Dartmouth-Wentworth-Thornton-Reed, or Baker-Carpenter-Sanborn, but much more closely integrated into a smoothly working team-unit than we ever have tried for previously on this campus.

Now I'm going to outline the circulation plan of the main floor of the Hopkins Center. A free efficient circulation to and from the properly placed major areas of activity is the foremost architectural problem of the Center. This is the arterial system through which the life blood of a building (its users) must move with ease and pleasure if the building is to be a success.

We enter from Wheelock Street into a broad and spacious and very well lighted entrance hall. In the foreground right and left are gently curving stairs that lead to the "Top of the Hop" lounge and campus observation area above. Directly ahead is the Theater and on either side are art exhibition spaces. Also ahead is a vista of green, the first of a series of garden courts, some small, some large, some fully, some partially enclosed. This emphasis on greenery, on landscaping both within and without the building, is a feature of the plan. We want to live with nature more intimately today than in the past. We no longer need to fear nature or hide from her, even in a Hanover winter. Our technology has made us more comfortable in more open shelter, and psychologically we are happier today with less demarcation between indoors and out. This feature of the Hopkins Center seems to be a very proper intensification of our outdoor tradition.

Returning to the entrance hall we notice a broad inviting corridor opening to the right flanked on one side by the Art Museum and on the other by a Sculpture Court. We move along this corridor and it turns south past the college mail distribution center (post office), the theater stage workshops, the studios for drawing, painting and architectural design, the snack bar and light refreshment dining area, and enters the lobby of the 900-seat music auditorium (which like the 450-seat theater will be used frequently for lecture and instructional purposes as well as music and drama purposes). At the northwest this corridor looks and opens out onto a garden adjoining the Hanover Inn. At the southeast it opens onto a spacious outdoor recreation and dining terrace (served from the snack bar) that commands a very large garden court (about one third the size of a football field) opening to the east.

Thus we have moved from the entrance hall and theater lobby at Wheelock Street west and south to the auditorium lobby and southern entrance hall at Lebanon Street. Along the way we have seen a variety of interesting exhibitions (associated probably with current drama, music, art or instructional programs) and through open doors and broad show windows we have been able to observe briefly many of the artistic activities, work in progress, that is the raison d'etre of the building.

On the lower floor, which is basement at Wheelock Street and, because o£ the slope of the land, above ground at Lebanon Street, the main north-south corridor is repeated. It connects music rehearsal halls and studios at the south with sculpture, ceramics, printing crafts, wood working, metal working and lapidary shops along the west to the theater rehearsal and work areas and the art storage and museum work areas at the north.

The activities of these two working floors of the Hopkins Center, so closely juxtaposed and so easily observed, will have very interesting educational intensifications and cross-fertilizations. There will also be many connections and associations between these activities and the regular courses and book learning studies of the College. The dramatic, visual, and aural arts go hand in hand with literary, philosophical, and scientific knowledge. Furthermore, there is surprisingly vital educational value in combining the mind, the eye or ear, and the hand in the process of creating some tangible thing from an idea or an intuition. What is achievement but the realization of plan through process? Creative activity in one or more of the arts can teach an eighteen year old a great deal about balance and order, about unity in diversity, about fitness to purpose, about harmony and beauty, not only in the arts but eventually perhaps in all of life.

Thus the purpose of the Hopkins Center is to provide an environment for creative activity, both active and passive, both doing and viewing, and the interrelation of many kinds of activity, both creative and recreative. The aim of the architecture is to facilitate rather than hinder this worthy purpose. This is the why of the extensive open plan, of the free swift flow of circulation, of the generous use of glass for observation in and out, of the varied and simple masses of the different parts of the building. The building committee believes that our architect, Mr. Wallace Harrison, is so sensitive to the purpose of the Center and so dedicated to the achievement of the architectural aim that Dartmouth is going to have not just a good building, but quite possibly an exceptionally fine building, an architectural work of art.

LET US go up now above the entrance lobby to the large social room that looks out over the campus. This is a special grandstand from which to watch the life of the campus. It is the Inn porch raised to a higher degree of magnitude. There will be no better vantage point from which to admire the charm and beauty of Baker tower. No other room in the building, not even the banqueting and informal social areas nearby, will give so much pleasure to the returning alumnus or visiting parent as this splendid "box seat" for the Dartmouth "spectacular," ever changing, ever the same.

Let us move out now on to the campus where we can get a better, fuller view of Dartmouth Row and where we can look back at the new Hopkins Center, placing it in our imagination a little further back and more to the east than the present facade of Bissell Hall. Why is the Hopkins Center in the contemporary style, a style which seems strange to many of us, and even quite shocking to some? Why isn't it in the Georgian style? Isn't Georgian the traditional architecture of Dartmouth?

The answer to the last question is both yes and no. Our earliest and best building, Dartmouth Hall, 1784-92, is Georgian, a rugged four-square country Georgian, that was later changed somewhat to go with the Greek Revival buildings, 1820-40, which flank it. Dartmouth Hall is our only authentic Georgian building. We have a number of buildings in various 19th century styles, mostly the later and poorer eclectic revivals, and we have quite a few buildings in the 20th century imitation of Georgian, some fairly good, some very poor. Certainly one real and very fine building, and then, more than a hundred years later, a sprinkling of imitative buildings hardly makes an outstanding tradition.

Let me start to answer the question as to why the Hopkins Center is not in the Georgian style by humorously calling your attention to the fact that the English throne is now occupied by a Sovereign named Elizabeth and the American White House by a President named Dwight. Georgian architecture, of course, got its name from the 18 th century English monarchs, George I, George II, and George III, and perhaps I might even add our own federal George, George Washington. The economic and social and political conditions that produced these men and the architecture that bears their name have long since passed away.

It is interesting to realize that Georgian architecture was not called Georgian in the 18th century. It was simply modern architecture and, very definitely it was not an imitation of any tradition from the past. No Georgian architect on either side of the Atlantic wished to imitate the Tudor architecture of Elizabeth the First. Eleazar Wheelock did not want to build a 17th century Gothic college hall such as Harvard had built a hundred or more years earlier. Why? Because the men of the 18th century wanted to stand on their own feet. They had self-confidence. They knew that things were changing, that they were making technological advances. It was an age of enlightenment. They were not only planning new buildings and new colleges, but also new nations and a new industrial order.

The Georgian architects by no means ignored the past. They studied it and learned a great deal from it but they were too smart to copy it. They liked simplicity and logic and order translated into rectangular and regularly arranged buildings. Their favorite materials were the most flexible and economical ones, wood and brick, not the carved stone of Medieval Europe or Renaissance Florence. Their colors were bold ones, white, red, yellow, colors that proudly set their buildings apart from nature. They liked light, and used far more glass in much larger unit sizes. They markedly improved heating, planning their buildings around uniformly spaced chimney stacks that would permit a fireplace in every room. They would not put up with the medieval custom of heating only one or two rooms in a building. Benjamin Franklin's invention in 1740 of the stove which bears his name is the starting point of both modern heating and cooking.

Now let's come back to Dartmouth Hall and notice how its size and shape are conditioned by its chimney stacks. Note its rugged rectangular bulk and its long low facade broken in the center by the slight projection of the gabled pavilion. See the generous window area and observe the relatively low pitched roof and graceful cupola. These were all contemporary features in 1784 and they indicate to us how clearly Eleazar Wheelock realized that he could put 18th century life only in 18th century forms. He certainly did not try to put the new college into 16th century architectural forms. Do you really want John Dickey to warp 20th century life into 18th century forms?

DARTMOUTH HALL is country Georgian, not the more decorated and sophisticated city Georgian of Boston, Newport or Philadelphia, and there is evidence that Wheelock wanted it that way. Two sets of plans were submitted to Wheelock in the 1770's, before the Revolution, and one of these was by a renowned architect, Peter Harrison of Newport. Unfortunately this plan no longer exists but we know that Harrison never designed a building as unornamented as the present Dartmouth Hall. We also know that Wheelock frequently expressed admiration for Nassau Hall, a plain and rugged college structure erected at Princeton. The Dartmouth Hall we have is very much in that plain and rugged tradition.

When it was built, after the Revolution, Wheelock found that he could not afford brick and must be content with the cheaper wood frame and clapboard siding. After the fire of 1904 it was restored to meet Wheelock's original desire for a brick building. Originally the windows were all the same size and there were no blinds. The present graduated windows and blinds reflect the architectural thinking, softer and more romantic, of the early 19th century. The projecting pavilion in the center indicates the difference in plan of that area as opposed to the wings. On the ground floor there was a meeting hall, on the second floor the library, and on the third floor the art gallery and museum. The wings of course were residential and in the early days some dormitory rooms also doubled in the daytime as classrooms.

We have George Ticknor's painting of Dartmouth Hall done in 1804 when he was an undergraduate. It shows us how well this beautiful building had been placed on the high ground east of the green. But it also shows how Wheelock's successor failed to appreciate this good site planning and had partially offset it by placing a chapel building almost in front of it. Fortunately this structure was demolished in the new building period of 1820-1840 when the very fine architect, Ammi B. Young of Lebanon, N. H., na- tionally famous for his Boston Customs House, added Wentworth, Thornton and Reed Halls and planned a twin to Reed for what is now the site of Rollins Chapel, It is a pity that this fourth building, due to a prolonged depression, was never built. (I would advocate its "restoration" even at this late date.) We should be eternally grateful, however, that we have the other three buildings, a magnificent group to run interference for the older "star." And in Reed Hall, I believe, we have a second masterpiece, a building echoing the strength and simplicity of Dartmouth Hall, intensifying the foursquare feeling, and adding subtleties of proportion and harmonious associations of solid and void that were the result of Young's passion to learn from that great source of the democratic spirit, " the Greeks. Reed Hall represents the architectural Greek Revival at its best, uncontaminated by literal imitation of Greek buildings.

It was the time when prophets like Horatio Greenough and Ralph Waldo Emerson were saying, "We do not honor the Greeks by imitating them, but rather by being creative as the Greeks were creative." They were pointing out that the Greeks never imitated the Egyptians, and that the true lesson taught by the Greeks was "to know thyself." At the time and in the main, Greenough and Emerson were voices in the wilderness but now, a hundred years later, they have been heard

I would like to assure you now that our architect, Wallace Harrison, knows well and loves deeply this wonderful row of Dartmouth buildings, the old "College on the hill." I can tell you that he has spent many hours of many visits, studying, measuring, absorbing, savouring this "best run" of our architecture. Mr. Harrison has known and loved Dartmouth for a long time. He received an honorary degree here quite some time ago. For many years he has been a contributor to our Alumni Fund. The integrity and beauty of our campus are uppermost in his mind and heart.

It is the underlying architectural quality of Dartmouth Row that Mr. Harrison wishes to continue and re-express in terms of our day and our building. The facade of the Hopkins Center will not, and should not, copy the appearance of Reed Hall in the same way that Reed Hall did

not copy the appearance of Dartmouth Hall. But the Hopkins Center can, and will, carry on the spirit of both previous buildings. It too will be four-square as it faces the green, a long, low, bold and rugged rectangle echoing the proportions of Dartmouth Hall and repeating again the dominant white color and the dark rectangular counterpoint of windows and doors. The Hopkins Center face will have more glass than Dartmouth Hall, but that is only natural. It must invite in far more students to participate in far more varied activities than existed here in 1790. And the upper floor is to be a place of outlook, a vantage point from which to see the campus in perspective, both the hurlyburly present and the glorious past. One cannot look out through opaque masonry nor should one look out at i960 from an imitation 1790 window. This horizontal upper-floor projection in the Hopkins Center facade emphasises outreaching qualities of our new building in the same way that the vertical projection in the center of Dartmouth Hall emphasises outstanding qualities in the public lecture, library, art gallery rooms there.

HERE is a quotation from an article by Nathaniel L. Goodrich in the Alumni Magazine for November 1915: I have a mental picture - a vision - a long low and simple facade, the restrained delicate and subtly adapted result of a living study of Old Dartmouth Hall, standing half revealed at the north end of the campus." Mr. Goodrich was dreaming of a new college library, a dream that was realized in different form a decade later in the Baker Library. Substitute the word south for north in Mr. Goodrich s dream and it lives again today in the Hopkins Center which, unlike Baker, is long and low and subtly adapted from Dartmouth Hall and will stand half revealed at the ... end of the campus." The Hopkins Center presents a very modest face to the campus. It is set back to a line with the Inn dining room, and it is only two stories high, not as high as the present Bissell Hall. Three rows of trees stand between it and the green.

Let's look out again at Baker Library and realize that its architect, Jens Fredrick Larson, was right in placing it a whole block back from the north end of the green so that it would not compete with Dartmouth Hall as overseer of the green (Webster Hall is the unruly one in this respect). Mr. Larson was also entirely right, in my opinion, in giving Baker Library its strong and monumental tower, a tower to dominate the entire college town and emphasize the library as the head of the institution. It is a tower that has both strength and grace and the library itself has considerable artistic charm. These qualities are far more important to me, especially in the context of 1926, than the reminiscence of sophisticated 18th century Philadelphia and its Pennsylvania State House.

In the Hopkins Center as it falls back toward Lebanon Street we will get glimpses of red brick and low pitched, perhaps gabled, roofs that will be a visual tie to Baker Library and other Georgian Revival buildings. Of course there will be no imitative Georgian ornament. The stage tower, a large upstanding necessity for any theater worth the name, will be a sky-line element. It is a big mass and there is no way in which to duck its size and height except at the expense of the efficiency of the theater. The answer to the problem is to accept it, to place it advantageously, and to proportion it as skillfully as possible. Mr. Harrison has accepted it, as has the whole building committee. He has placed it as far back from the campus (half way to Lebanon Street) as is consistent with the other, even more important factor of keeping the theater in the approximate center of the whole group of activities. It will be of red brick and it will be well-proportioned. It will be visible certainly but it will not look any higher than the Hanover Inn. Perhaps I can reassure you by pointing out that, although it will rise 68 feet above the level of the campus, Baker Tower rises 200 feet plus, and the heating plant chimney rises 175 I do not believe that many people will dislike the Hopkins Center stage tower. In fact I predict the contrary. I can see it in 1977 sedately clothed in both tradition and ivy. Incidentally Georgian architects despised ivy; that was only for ancient Gothic buildings.

Henry B. Thayer of the Class of 1879 writing in an article on "This New Library" in the Alumni Magazine of November 1928, said: "It was the trained artistic eye of Professor Ames .. . which gave Baker Library its individuality." Professor Adelbert Ames until his death in 1955 was a prime mover in the present Hopkins Center project and an enthusiastic exponent of this building being a contemporary work of architecture. The building committee with all its collective mind and spirit wishes most ardently that "Del" Ames' "trained artistic eye" could follow each evolving step in the realization of this project which was so close to his own heart.

I HAVE complete confidence that Profes- sor Ames would concur with every reason that I have put forward as to why the Hopkins Center should be in the contemporary style. Let me state these reasons once again, in summary, but not necessarily in the order in which they have already been presented:

1. It is the true tradition of Dartmouth to be contemporary, to meet the architectural problems of our day as forthrightly as in the days of Wheelock.

2. It is our duty to know and cherish our architectural heritage, to understand the basic values of simplicity, strength, dignity and grace in Dartmouth Row, and to create in the spirit of these values.

3. It is worthy for us to try to conserve and continue qualities of shape, proportion, color and texture from the good buildings on our campus, but it is not worthy for us to devalue and cheapen these buildings by repetitive imitations.

4. It is right that our building face the campus modestly, without historical or stylistic pretensions, in order that Dartmouth Hall and Baker Library remain the focal points of the campus.

5. It is desirable that the facade be open and bright with glass so as to welcome all in and to offer all a broad and satisfying outlook.

6. It is necessary, for practical and economic reasons, that this building be an efficient unit of multiple parts, and not a single gigantic box dwarfing the other buildings of the campus nor a series of actually separate buildings inefficiently and expensively connected by arcades.

7. It is essential that this building have the free and flexible flow of circulation that is possible only in the contemporary style and without which the main purposes of the project could never be realized.

8. It is delightful that this free contemporary plan allows and enhances our contact, both inside and out, with Mother Nature on old Hanover Plain.

Let me conclude with another quotation from Henry B. Thayer's article of 1928: "No alumnus with a spark of imagination can come back to a class reunion and see Baker tower rising above the elms, see it illuminated at night, hear the chimes at twilight, see the beautiful interior and think of what it is going to mean in the education and life of generations of Dartmouth men to come, without feeling a thrill such as rarely comes in this sophisticated world." How right Mr. Thayer was! The thrill still exists today and long will continue from both old and new vantage points, and may I be so bold as to make a new prophecy in this same tradition and with deep respect to Mr. Thayer.

No Dartmouth man with a spark of imagination can return to the campus and see the broad welcoming facade of the Hopkins Center nestling among the elms, see it dappled with northern sunlight, see it illuminated at night, partake but a little of its creative riches, observe only a few of its life enhancing activities, and think of what it is going to mean in the education and college life of generations of Dartmouth men to come, without feeling a thrill such as rarely comes in this sophisticated world.

Professor Lathrop has been a member of the Dartmouth faculty since 1928 and is Director of the Carpenter Art Galleries as well as Professor of Art. He teaches courses in mediaeval art, Renaissance art, and modern art. He is a member of the Hopkins Center Building Committee.

Special Alumni Subscription To THE DARTMOUTH See page 5

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Commencement Address

July 1957 By DOUGLAS HORTON, D.D. '57 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1957 By JAMES M. O'NEILL '07 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1957 By LLOYD L. WEINREB '57 -

Feature

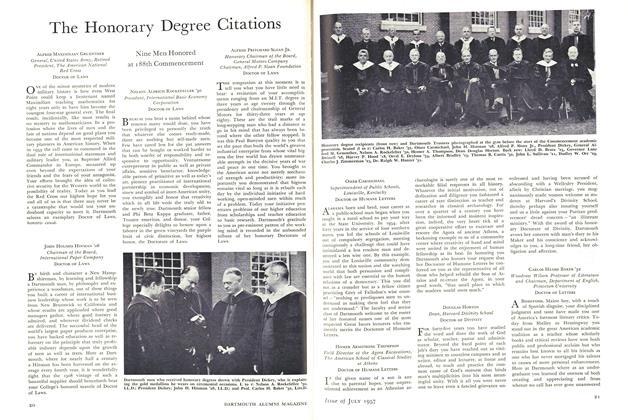

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1957 -

Feature

FeatureThe 1957 Commencement

July 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1957 By DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54

CHURCHILL P. LATHROP

-

Books

BooksIT'S A LONG WAY TO HEAVEN

February 1946 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Books

BooksMEDIEVAL MENAGERIE

March 1953 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Books

BooksCAVE DRAWINGS FOR THE FUTURE.

June 1954 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Books

BooksART AS AN INVESTMENT.

January 1962 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Feature

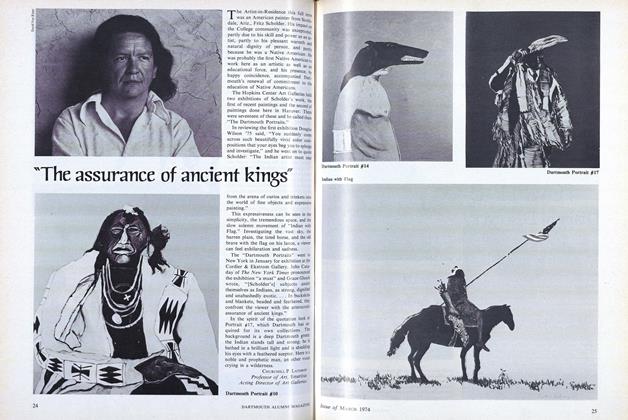

Feature"The assurance of ancient kings"

March 1974 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Feature

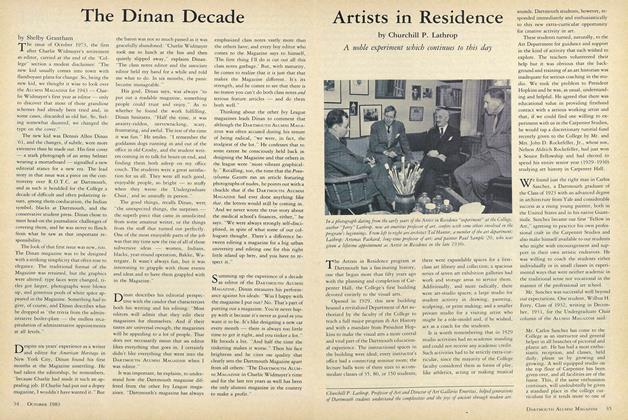

FeatureArtists in Residence

OCTOBER, 1908 By Churchill P. Lathrop

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDogs Clamantis in Deserto

MAY 1992 -

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

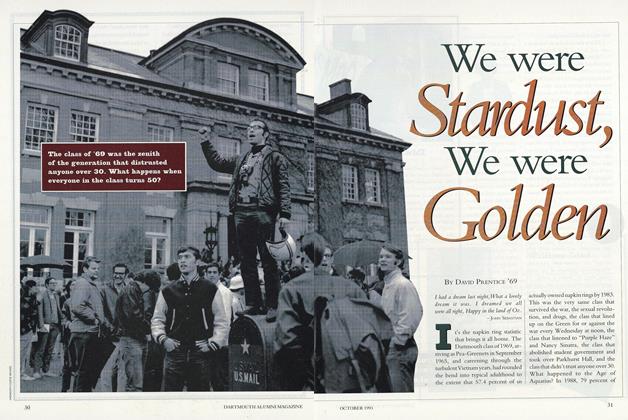

Cover StoryWe were Stardust, We were Golden

October 1993 By David Prentice '69 -

Feature

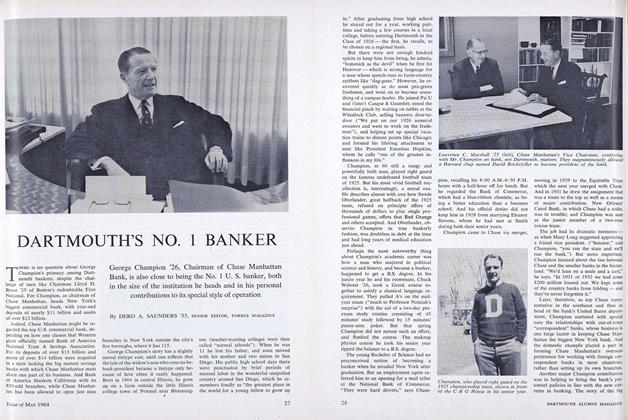

FeatureDARTMOUTH'S NO. 1 BANKER

MAY 1964 By DERO A. SAUNDERS '35 -

Feature

FeatureLife on Campus Is Slated for an Overhaul

June 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

FeatureCreativity: The Open Dance at Dartmouth

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Prof. Blanche Gelfant