One of the most controversial and mis-understood activities at universities today is "affirmative action." Federal legislation, as well as an Executive Order, require us to comply with affirmative action rules in our hiring policies. While non-discrimination in hiring has long been a federal policy, there was a significant shift when the government determined that institutions in whose labor force women or minority groups were under-represented had to do more than simply not discriminate - they had to take affirmative action.

It is a common misconception that the federal government is forcing us to hire women or minorities in preference to better qualified white males. Not only is this false, but as an HEW directive of December 1974 makes clear, it is against the law to practice such discrimination.

Ordinary discrimination is simple to characterize. For example, the departmental chairman who says "I know that there are women Ph.D.s in my field but they're simply not as good as the male Ph.D.s" is clearly discriminating. Affirmative action is aimed at the much more subtle form of discrimination that was traditionally practiced by many recruiters who were not at all aware of the effect of their actions. It is not uncommon in academia for a departmental chairman to call a few friends at other institutions to ask for the names of their students who might be qualified for a given position. If all these friends are white males and most of their students are white males, the outcome is almost preordained. Or if a college limits its search for an administrative officer to alumni of the college, and if these alumni are all males and most of them are white, there may again be indirect discrimination.

It is important to record the fact that the Trustees approved our first affirmative action plan early in 1972, before we were contacted by any federal agency. While the details of implementation have been vastly improved since that time, and while we have since been required to go into much more complex record-keeping and reporting, the principles of that plan are still in force today. The Trustees took the original action as a matter of conscience, not in response to federal regulations. We recognized that in an institution which for more than 200 years had a male student body, there must certainly have been discrimination against women in the selection of faculty and administrative officers. There is little use now in arguing the question of whether more women faculty members would have been healthy even for an all-male institution, but there was no doubt that after coeducation we could not defend the almost total lack of women among our officers. While there was no evidence that similar discrimination had existed in recent history against black officers, the location of the College and its overwhelmingly white student body served as a deterrent to minorities to apply for positions. Therefore, the Trustees were in favor of affirmative action.

The main requirement of our plan is that we advertise jobs widely enough to give a reasonable chance of attracting qualified women and minority candidates. If our original attempt to create a balanced pool of candidates is not successful, we take further steps to enrich the pool. If evidence then proves that there is a great dearth of women or minorities in the particular specialty, there is nothing to prevent us from filling the position from the available lists. A second requirement is that if qualified women or minority candidates do turn up in the pool, we must include them in our "short list" of candidates whose qualifications are carefully examined. I want to emphasize again that, after all jobrelated criteria have been given due consideration, it is the best qualified candidate who should be hired. Credentials of all the most promising candidates, whether female or male, minority or white, must be compared to determine who is best qualified.

So much for the principle of affirmative action. The principle is very clear; in practice nothing is ever quite so simple! All other things being equal, it is to be hoped that a department with no female faculty members will hire an equally qualified woman in preference to another male faculty member. But two people are hardly ever equal, and perhaps no two members of the department will completely agree on the qualifications of the candidates. I have evidence that at many institutions the fear of losing federal funds has led recruiters to lean over too far in their affirmative firmativeactions. I have no doubt that charges that affirmative action has led to lower standards at some institutions are true. But I have no evidence at all that this has happened at Dartmouth. On the contrary, the fact that we have advertised our jobs more widely has led to a stronger and more diversified faculty and administrative officer corps today than we would have had without this extra effort.

In the three years since the original plan was adopted we have had spectacular success. The number of women faculty members has more than tripled, growing to 12 per cent of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. The number of minority faculty members has increased from 4 to 16. In the administration, women were better represented in 1972, but the number has almost doubled to 23 per cent of all administrative officers. The number of minority administrators has increased from 5 to 16. It is clear that these increases have considerably strengthened both our equal opportunity program and coeducation at Dartmouth. But as I review in my mind qualifications of many of these new officers, I know that Dartmouth is a better institution for all students today.

This does not mean that our affirmative action plan is free of problems. While we have good luck both in recruiting and retaining women, we have not had equal luck in retaining minority officers. Our geographic location, which is such a great asset to the institution in other ways, is a handicap in this case. The far northern location and the considerable distance to the nearest metropolitan area makes Dartmouth less attractive to many minority candidates. They also have a feeling of living in an overwhelmingly white community. One must recognize that the supply of highly qualified minority faculty members and administrators has yet to catch up with the enormous nation-wide demand. Therefore, they can improve their earnings appreciably by several changes in jobs - just as mathematicians did 15 years ago. Many institutions, to make sure that they get the best qualified minority candidate, have been prepared to pay a considerable premium. We have resisted, as a matter of policy, opening a wide gap in salaries based on race. While we want to attract the very best minority candidates, we also know that large salary differentials create very bad feelings amongst colleagues.

The problem with women is different but equally complex. Many academic institutions had an indefensible practice of hiring women candidates only for irregular faculty positions. Dartmouth was no exception, and we have had to take corrective action. We have also had to review the position of women in staff and officer jobs to make sure that women are not classified at a lower grade than men carrying comparable responsibilities.

A particular problem that we must face as a nation is the desire of both husband and wife to carry on a career. Here, our location in a small town has again been a handicap. In a large city both breadwinners of the family can find satisfying careers, usually at different institutions. We have abolished all rules banning husband and wife from both working for the College, but given the limited number of jobs in and near Hanover we have only rarely been lucky enough to find a- position for both of them.

A significant step that has helped the development of dual careers has been the creation of a number of part-time positions in the faculty, administration, and staff. For example, we now allow faculty members holding half-time appointments as assistant professor to compete for tenure positions. Instead of the usual six years for a tenure decision, we have extended the period to nine years to give them a fair chance for professional development. We then allow tenure appointments that are half-time. It is interesting to note that this option has proved attractive to both men and women.

The greatest burden imposed by affirmative action is the vast amount of red tape. Advertising adds enormously to the cost of recruiting. We are required by the federal government to keep extensive records of every recruiting experience. Reports required by HEW run into hundreds of pages and have placed a major burden on all administrators at the College. I don't know how we could possibly cope with these demands today but for our new management information system. It is ironic that at a time when the federal government has made major reductions in aid to higher education, it has been responsible for generating vast in creases in administrative costs. To be fair, I must note that the new federal regulations have contributed to better management practices. The College has become more efficient and is more responsive to the needs and aspirations of its employees.

We have been most fortunate in the caliber of our two affirmative action officers, first Assistant Dean Gregory Prince, and now Professor of Drama Erroi Hill. I owe a particular debt to Professor Hill for his amazing accomplishments in a year and a half, and for the willingness of an outstanding faculty member to take on such an unpopular burden.

Features

-

Feature

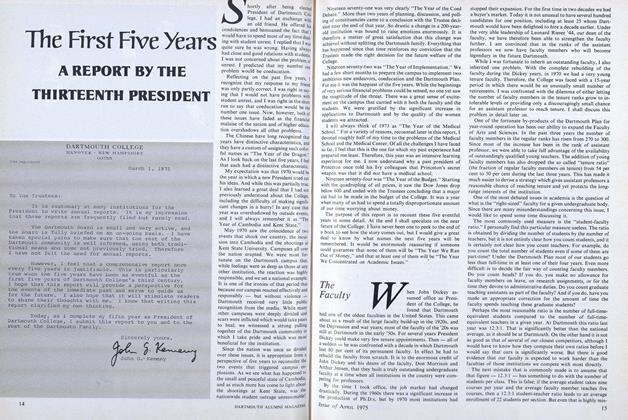

FeatureClass of 1962

-

Feature

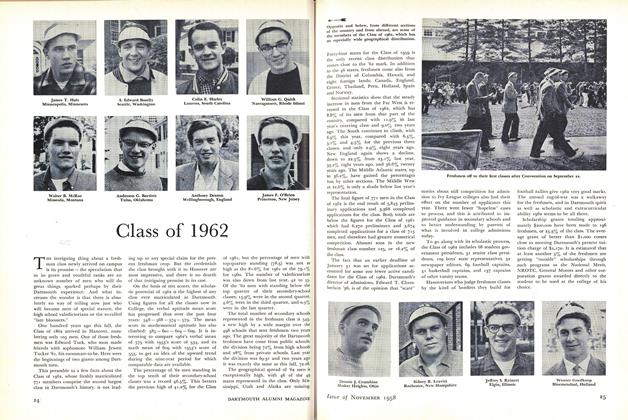

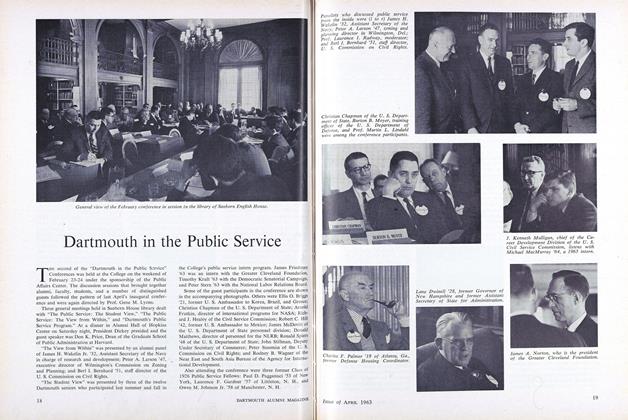

FeatureDartmouth in the Public Service

APRIL 1963 -

Feature

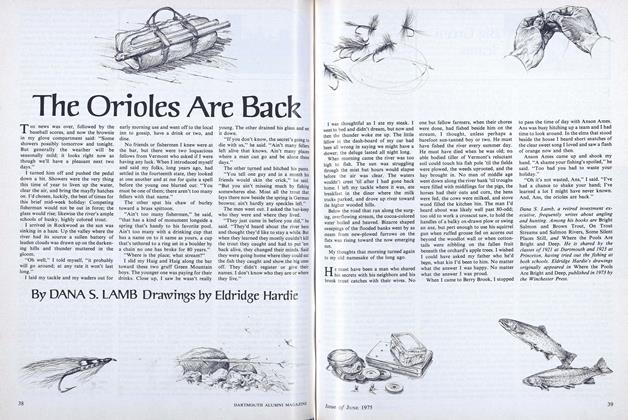

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Feature

Feature"Hoppy" on His Early Dartmouth Years

DECEMBER 1966 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

Feature"ring O bells!"

November 1974 By ELIZABETH F. MOORE -

Feature

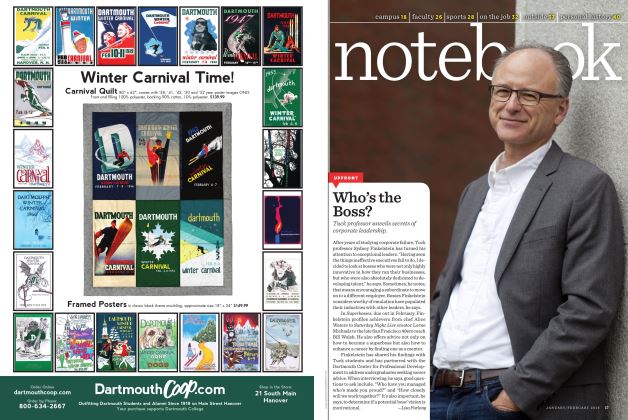

Featurenotebook

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By LAURA DECAPUA PHOTOGRAPHY/TUCK