By Richard Eberhart '26.New York: Oxford University Press, 1957. 72 pp. $4.00.

This good new book reminds us that Richard Eberhart has been and still is something of a maverick among modern poets. No one can make him the member of a school or the follower of a trend - or even the leader of one. He has been touched, of course, by the winds of doctrine and fashion that have blown through the poetry of the last thirty years. But he hasn't been blown off his course by any of them; he has turned each one - sirocco from the desert or north wind from the end of the world - into his own music, and has gone on his way rejoicing. It is indeed his manner of rejoicing that marks him out as a poet, and that gives, more particularly, a vivid individuality to the "great praises" of this latest volume. Sometimes his praise goes to the sensuous beauty of the natural world, caught in an instant when a penumbra of mystery surrounds it: By a Spring meadow I lay down by a river And felt the wind play on my cheek. By the sunlight

On the water I felt the strangeness of the world. Prone in the meadow by the side of the fast brook I saw the trout shooting his shadow under the willow.

This stanza is not only enchanting in itself, but is nicely appropriate to the theme of the poem in which it occurs, "Centennial for Whitman"; for it echoes, with a deliberate difference, the moments of strangely heightened perception (passive in appearance but active in effect) which break into even the dullest parts of Leaves of Grass.

Natural beauty is evoked in another fashion this time distantly reminding us of Wallace Stevens, though still bearing the unmistakable Eberhart signature — in the serenity and fullness of "Summer Landscape." But Eberhart's muse is a stranger to the harmony of nature as often as she is at home in it. Most of the praises of this book are achieved on the far side of bitter conflict and struggle, of death itself:

The deaths of others first offend Seasoning our love with corpses. Then we look into the mirror To see if we have other resources.

None shows.

("On Getting Used to the World")

It is out of this bleak clarity, and not only out of his abounding perception of delight, that the poet builds his triumph, the old and yet always new one of life won from death:

... I recall in the Campo Santo, at Pisa, The work of medieval Giovanni

Who painted an old man, prone and dead, An infant, the soul, springing from his head.

("The Wisdom of Insecurity")

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

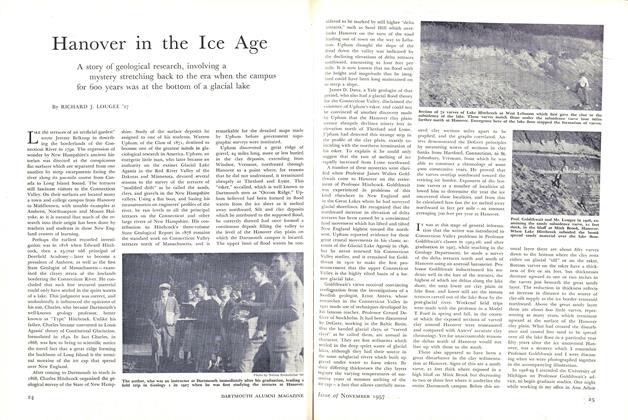

FeatureHanover in the Ice Age

November 1957 By RICHARD J. LOUGEE '27 -

Feature

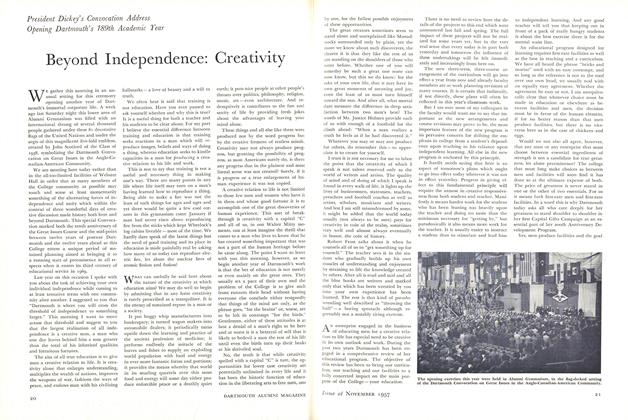

FeatureBeyond Independence: Creativity

November 1957 -

Feature

FeatureGlass Funds and the Capital Campaign

November 1957 -

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Form Association

November 1957 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

November 1957 By WILLIAM L. CLEAVES, F. STIRLING WILSON, RODERIQUE F. SOULE1 more ...

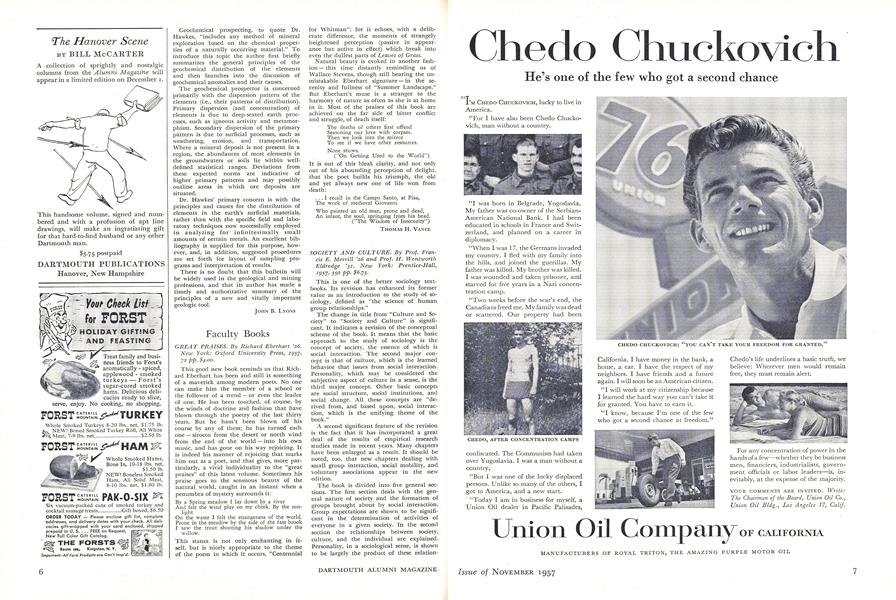

THOMAS H. VANCE

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

June 1934 -

Books

BooksSECONDARY SCHOOLS FOR AMERICAN YOUTH

June 1944 -

Books

BooksFive of a Kind

OCTOBER 1982 By Gregory Rabassa '44 -

Books

BooksGalaxies

November 1979 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksAPPLIED PSYCHOLOGY,

November 1948 By Samuel Feldman. -

Books

BooksJesus and His Bible.

JANUARY, 1927 By William H. Wood