IT'S not the most wonderful trip up here," Albert H. Washburn wrote on the evening of April 1, 1919. "After passing Concord the train gets to be very much of a local. I got off at Norwich . . .

right across the river. There were a good many boys on the train coming in at the last moment. A half-dozen busses drawn by horses were lined up at the little country station and I managed to make one of them. Many of the boys walked either from necessity or preference. The distance is not great, but there is a steep hill to be conquered before you get here."

A few minutes earlier Dartmouth's new Professor of International Law had checked in at the Hanover Inn, "an attractive looking building of brick," and found his room which "looked out over the campus, comfortable and really firstclass."

Professor James P. Richardson introduced Washburn to his first class at ten the following morning. "It doesn't have to be quite so heavy! Remember, you're not before the Supreme Court," Richardson suggested after class. Washburn recorded that it "went very well," but that he "must be a little careful not to talk over their heads. They are, after all, college boys primarily and not students of law."

Such was the beginning of Albert Washburn's three years on the Dartmouth faculty—years which, in his own estimation, were the happiest and most rewarding of his life.

Dartmouth men soon came to know Washburn as "the Prof Who lives at the Inn." Members of his classes noted that he wore "a different suit each day." Only later did they learn that their teacher was dean of the New York Customs Bar and could well afford such impeccable attire. Behind him, in the year 1919, were seventeen years of public service and a decade and a half of highly successful legal practice. Ahead lay eight years of distinguished service as U.S. Minister to Austria.

A native of Middleboro, Massachusetts, Washburn worked his way through Cornell University as private secretary to ex-President Andrew D. White and President C.K. Adams. It was White who advised him to enter the foreign service and save enough to finance the study of law. As a Cornell senior Washburn campaigned for the Republican ticket of 1888, attracting the attention of party leaders who rewarded him with appointment as U.S. Consul at Magdeburg, Germany. At the sugar metropolis of the German Empire his strict enforcement of regulations and attempts to halt illegal exporting practices brought from the Magdeburg Chamber of Commerce protests and unsuccessful demands for his removal. Inefficiency and dishonesty prevalent in the politically appointed consular service aroused his life-long interest in foreign service reform. The Department of State regarded Washburn as a competent young officer and published a number of his reports. But when the Democrats regained power in 1895 they dismissed him. Asked to accept another post a few weeks later, he had already agreed to become Senator Henry Cabot Lodge's private secretary.

While serving Lodge until 1897 Washburn took a law degree at Georgetown University and special legal training at the University of Virginia. Lodge and his young secretary became good friends and subsequently maintained a close personal and political association. For Washburn Lodge's political welfare came first and the Senator, who never hesitated to reward this loyalty, was the important factor in Washburn's later appointment to public office. As Lodge's trusted aide, mender of political fences, and campaigner, he broadened his own contacts in Massachusetts and on the national level.

Shortly after establishing the partnership of Washburn and Stetson in 1897, Washburn was appointed Assistant U.S. Attorney for Massachuetts, where he was placed in charge of customs suits in the district. This was the beginning of his specialization in the intricate problems of tariff law and the importing business. He assisted the prosecution of the celebrated "Mate Bram" trial growing out of the murders on the barkentine Herbert Fuller. In June 1901 he moved up as Special Counsel before the Board of General Appraisers charged with protecting Treasury Department interests in appeals for reappraisal and reclassification of imports. His work attracted the attention of Albert Comstock, a prominent New York customs lawyer. Forced to retire because of ill health, Comstock offered his frequent adversary a partnership which Washburn accepted in late 1904.

After Comstock's death the following year, Washburn became senior partner and soon brought three new members into the firm. Immediate success in private practice moved him into an income bracket many times beyond that of his government salary. He was well on his way to financial independence when in 1906 he married Florence Lincoln, the only daughter of a prominent and wealthy Warren, Massachusetts, couple.

Representing importers caused Washburn to reverse his high tariff views. He became an unofficial spokesman and publicist for importers, holding that well-organized pressure groups exerted disproportionate influence on tariff legislation to the detriment of the nation's economy and importers' welfare. Several of his articles advocating a scientific tariff and a tariff commission circulated widely in publications such as Forum and NorthAmerican Review. In other articles and before Congressional committees he championed reform of customs administration. His briefs and arguments in several cases attracted international attention involving as they did interpretation of the mostfavored nation clause. The Norwegian government in 1914 decorated him for his services in the American Express Company Case growing out of President Taft's ill-fated Canadian Reciprocity Agreement of 1911. Washburn's professional standing was recognized by his selection in 1917 as the first President of the Association of the Customs Bar.

FROM 1917 to 1919 Washburn served as delegate to the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention assuming a prominent part in its proceedings. The convention was responsible for his move to Dartmouth. At the Boston sessions he had worked closely with Dartmouth's James P. Richardson. "I have quite enjoyed the respite from office activities," Washburn wrote in 1918, "and I am threatening not to resume in the same old way." A year later Richardson urged him to carry out his threat. Dartmouth's President Hopkins, keenly aware of how World War I had altered America's position in the international community, believed "... the older subjects of the historic curriculum must be supplemented by social science courses to an extent unknown heretofore," and asked Richardson to recommend a Professor of International Law. Washburn accepted Dartmouth's offer of this professorship, hoping he could "invest the subject with something of living interest."

Stronger in research than in the classroom, Washburn's reputation as a teacher varied with the individual student. His interest in public affairs had found expression previously in numerous popular articles in periodicals. During his years at Dartmouth he contributed several technical articles on his subject to professional journals and reviews along with a Forum article partially supporting Lodge's opposition to President Wilson's "League." His writings and speeches advocated a prominent role for Congress in the conduct of foreign relations. He believed the United States would and should join a "League" of some kind and insisted he was not pleading for a policy of isolation. He contended that the American people did not understand and therefore were not prepared to assume the obligations imposed by Article X of the League Covenant.

During the 1920 campaign Washburn resumed a more active role in Republican politics and took "the stump" for Senator George Moses of New Hampshire. After Harding's election, Lodge, Vice-President Coolidge, and the Massachusetts Congressional delegation supported his candidacy for a European diplomatic post. Senator Joseph T. Robinson, Democrat of Arkansas, a University of Virginia classmate, demanded that Washburn receive the Bern post. Lodge also wanted Washburn assigned to Switzerland, but felt responsible for Joseph C. Grew. Robinson tried to block Grew's confirmation to Bern, but Lodge forced it through during Robinson's absence after arranging to send Washburn to Vienna.

WASHBURN reached Austria in June 1922 — a time of financial crisis for the new republic - and soon became a strong advocate of prompt action to save it from complete fiscal collapse. He played a prominent part in obtaining the League of Nations loan for Austria in 1922-23, and during the period 1927-29 again used his influence to help Austria float a longterm external loan. His work in connection with the financial rehabilitation and extension of credit to the struggling republic was a significant, if not a decisive, factor in its survival. He negotiated and signed several important treaties with Austria and his carefully prepared despatches were highly regarded by the Department of State. With some success he worked for a cultural rapprochement between Austria and the United States, actively supporting student exchange, assuming leadership in the Austro-American Society and promoting the Austrian tourist trade.

In addition to his regular diplomatic duties Washburn served ably at The Hague in 1922-23 as U.S. delegate to the Commission to Revise the Rules of Warfare established by the Washington Conference of 1921-22. As president of an arbitration commission he helped untangle commercial disputes between Austria and Yugoslavia.

During eight years of service under the Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover administrations Washburn came to consider him- self a part of the career service. By training and experience he was well qualified for diplomatic work. Although isolationist sentiment during the 1920's generally precluded spectacular performance by American diplomats, the few pressing problems Washburn encountered he met with decision and dispatch. One of his strong points was his ability to work closely with the several Austrian governments. Another was his influential political contacts at home to which he turned for support of programs he deemed to be in the best interest of the United States. Educated and cultured himself, his sensitivity to the Austrian cultural tradition made him particularly suited for assignment to Vienna.

The Washburns excelled in the demanding social responsibilities connected with diplomatic service. For Americans abroad the Minister's residence was "a home away from home." There Florence Washburn "reigned as the uncrowned queen of the diplomatic corps," a Time correspondent observed. "The Washburns did not stint themselves, and their dinners, balls, and receptions highlighted the Vienna social season."

Early in 1930 Washburn was called home for conferences and informed that President Hoover had selected him as Ambassador to Japan. But in his place went Joseph C. Grew for a tour of duty covering the historic- decade that culminated in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Just a few hours after returning to Vienna to close out his business and receive Austria's highest honor Washburn died of blood poisoning resulting from an apparently harmless scratch.

His death was followed by a flood of tributes. Secretary of State Stimson praised his "long career of public service at home and brilliant, successful service in Vienna." Responding to condolences from the Austrian government President Hoover said, "I consider this government has lost one of its most able diplomats." The City of Vienna declared two hours' mourning the day of Washburn's funeral, all work stopped, and thousands lined the street as his body was carried to the grave.

"Dislike of personal publicity prevented Minister Washburn from being as wellknown as he deserved to be," The NewYork Times observed editorially, "yet, his quiet modesty in no way lessened his capacity for service." In the editorial columns of the New York Herald Tribune young Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. wrote that Washburn's death would "call forth deep regrets from all who are familiar with his contributions to the welfare of Central Europe and from all who appreciate distinguished service from Americans in the foreign field. ... The American people have lost a public servant of exceptional worth."

But of the many editorial tributes that appeared Washburn would probably have been most pleased with the observations of The Dartmouth:

Educators in general and college professors in particular hold a peculiar position in the undergraduate mind. ... It seems extraordinary that these men would forego a life of contact with men of their own age and interest to stand up and talk to a room full of intellectual striplings. There must be something wrong somewhere. Thus reasons the undergraduate. And tradition has offered an expla- nation. It's very simple: the poor old boys submit to such an existence because they can't get anything better to do. The most tremendous bomb-shell for this particular illusion is to be found in the life of Dr. Albert Washburn who died in Vienna a few days ago. ...

He was a Professor at Dartmouth.

The papers of the late Professor Albert H. Washburn, totaling fifty file boxes, have recently been deposited with Baker Library by his son, Dr. A. Lincoln Washburn '35, Professor of Northern Geology at Dartmouth. Mr. Stelck, the author of this article, sorted and organized the papers in connection with the writing of his graduate dissertation, "The Public Career of Albert Henry Washburn." Mr. Stelck is now Assistant Professor of History at Los Angeles State College. While in Hanover to work on the Washburn papers he was part-time assistant with the Great Issues Course.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshmen

December 1957 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Feature

FeatureStymied in the Bowl

December 1957 -

Feature

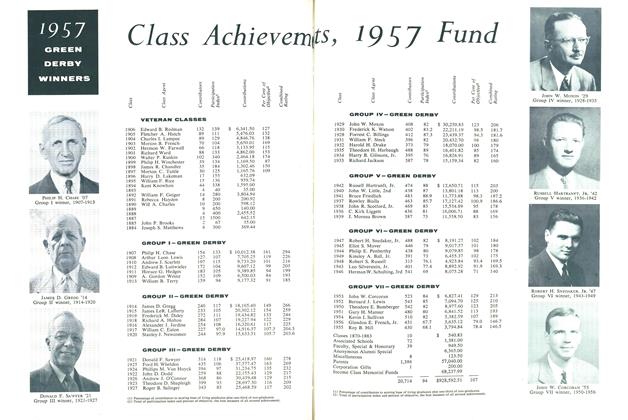

FeatureClass Achievemts, 1957 Fund

December 1957 -

Feature

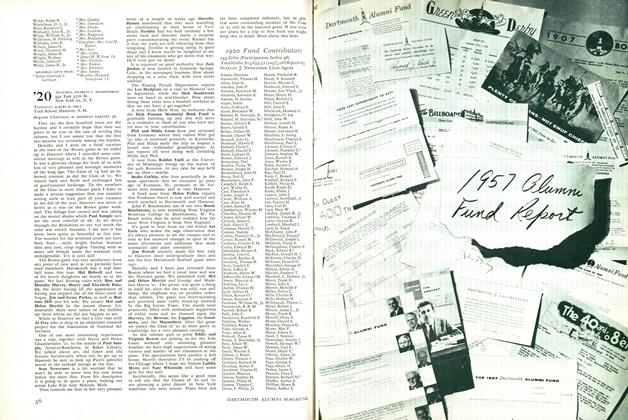

FeatureChairman's Report

December 1957 By William G. Morton '28 -

Feature

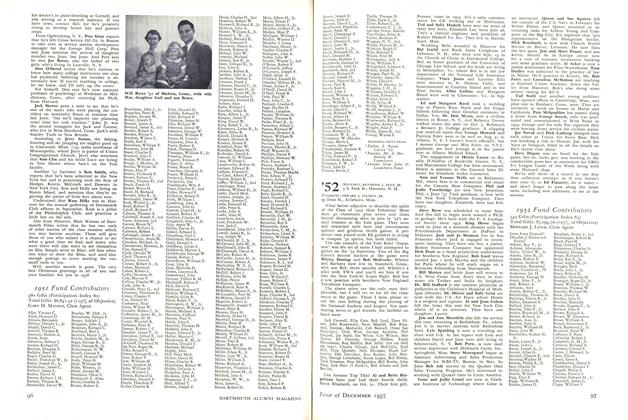

FeatureDevelopment Program Leaders Named

December 1957 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

December 1957 By RAYMOND J. BUCK JR., EDWARD J. FINERTY JR.