A Portrait ofRobert Frost. By Sidney Cox. New York:New York University Press, 1937. 177 pp.$3.75.

"The portrait of a famous man and a great poet, this book records a Damon-Pythias friendship over four decades." Thus do the publishers characterize, on the dust jacket, the late Professor Sidney Cox's book on Robert Frost. Actually, the book is not at all a record of a Damon-Pythias friendship, and I suppose that we should be thankful that it isn't. To be sure, Professor Cox's portrait of Frost springs from a devotion - indeed, almost a dedication to his subject, but the direction of his gaze is steadily and often acutely upon Robert Frost, rarely upon himself. From his years of privileged proximity to Robert Frost, Sidney Cox tried in this book to hold in focus the multitude of observations which he had gathered at close range. His problem lay in preserving, for his readers, the sense of intimacy with his subject and at the same time gaining a perspective upon it; his book is at once an answer to and a triumph over that problem.

For we are close to Robert Frost throughout the book. So much is Frost in the foreground that we are likely to forget the long and attentive listening expended to bring us this transcription of Frost's conversation. We are the ones who profit from Professor Cox's quiet expense, for the conversation he reports is brilliant, containing as it does the thoughts of a superior intelligence upon two primal subjects: education and poetry. By allowing Frost to speak for himself, by giving us the privilege of overhearing the long conversation, Professor Cox manages to make us see why Frost was the wisest man he knew. Whether or not we agree with what Frost says - and Frost would certainly not expect us to agree at all times - he emerges in the course of the book as the character of heroic proportions which his listener evidently believed him to be. We begin to see that Frost has spent much of his life alone, walking the dim boundary line between common sense and mystery and always refusing to be quite lost in either realm. For those who insist upon simplifying experience, Frost's position may seem more like fence straddling than heroism; but if we grant the shadowy nature of the borderland which Frost explores, we recognize the absolute restraint required of the lonely traveler, a restraint not unlike that of Marlow in Conrad's Heart of Darkness. Indeed, Frost is also engaged in penetrating the wilderness of our inner existence; even as he charts the landscape of ourselves, he reclaims for us a portion of the unknown life which charges existence with awareness.

That is why the thesis of Professor Cox's book, insofar as it has a thesis, is that Frost's dialectic moves searchingly between the poles of form and idea, of beauty and terror, of communion and loneliness, of Earth and Heaven. That is why, after all, Frost is a "swinger of birches." Although Professor Cox occasionally allows his own style to become unnecessarily Frosty, he nevertheless manages to give us invaluable insights into the mind behind the poems as well as some keen comments upon the poems themselves. He has written a book which will have value for anyone who wishes to have a closer glimpse of a major poet.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThirty Years After

June 1957 By RICHARD W. HUSBAND '26, -

Feature

FeatureAssignment: Antarctica

June 1957 By DON GUY '38, -

Feature

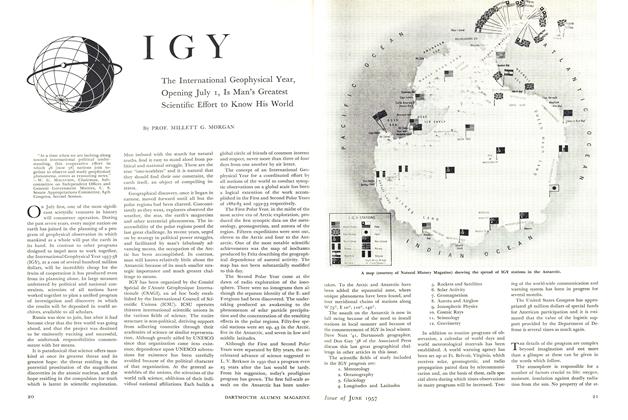

FeatureIGY

June 1957 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN -

Feature

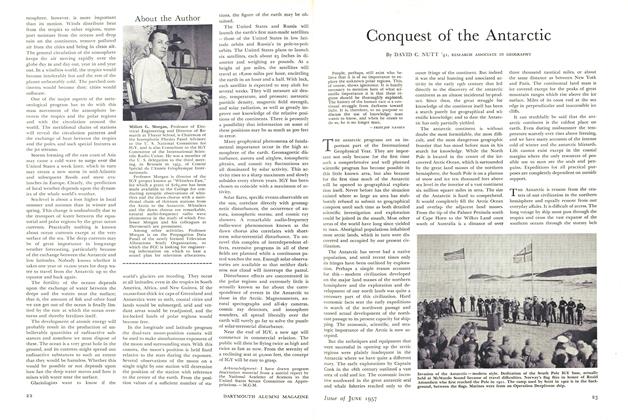

FeatureConquest of the Antarctic

June 1957 By DAVID C. NUTT '41, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

June 1957 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, FREDERICK K. WATSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1957 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR

Books

-

Books

BooksTHE NATURE OF PATENTABLE INVENTION

October 1946 By ALVAH W. SULLOWAY -

Books

BooksTHE TRUCK SYSTEM.

April 1961 By DAVID ROBERTS -

Books

BooksPADRE PORKO: THE GENTLEMANLY PIG

December 1939 By Hebbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksTHE SIX LOVES OF "SHAKE-SPEARE."

OCTOBER 1958 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksFREEDOM OF SPEECH BY RADIO AND TELEVISION.

APRIL 1959 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksMESSAGES OF THE BODY.

November 1974 By VIRGIL ALLEN GRAF