By A. J. Liebling'24. New York: Viking Press. 1956 306 pp. $3.95.

This book is indeed ambitious, for Mr. Liebling has attempted to write a serious history of boxing's modern era, that period covering the decline and fall of Joe Louis followed by the rise and reign of Rocky Marciano. The difficulties facing Mr. Liebling become apparent when we consider the strategies to which he is reduced in essaying such a project. First, his book is a collection of on-the-spot reports, many of which appeared in The New Yorker, covering important fights during the past ten years. This is possibly the only schema appropriate for describing a world whose defining attribute is incredible flux. Only by re-creating the moment in our memories can Mr. Liebling capture and illuminate the nature of his subject, and he quite rightly adopts the intensive rather than the extensive approach to his material, concentrating primarily on two figures, Marciano and Ray Robinson. Second, the only avenue Mr. Liebling finds open to reach high seriousness is that of mock-seriousness. Thus he sees the Moore-Marciano brawl as comparable to Ahab's (Moore's) struggle with the whale (Marciano); and he establishes a sense of traditional genre by constant allusion and tribute to Pierce Egan, whose Boxiana was the first great chronicle of boxing. Maintaining his mock-heroic stance, Mr. Liebling variously refers to Egan as the Herodotus, the Thucydides, the Sire de Joinville, the Froissart, and the Holinshed of the London Prize Ring.

But where Egan, who was creating his own public, could go rather fearlessly forward, Mr. Liebling has to tread lightly and carefully between two already established audiences: The New Yorker audience, trained to expect the sophisticated and clever; and the yawning sports world at large, whose inhabitants have come to accept athletic prowess as real heroism. To find a style which will somehow communicate to both worlds calls on all the resources of the writer, and we may pardon Mr. Liebling for sometimes taking both directions at once as he does, for example, in ending his discussion of the Moore-Marciano imbroglio: "It was a crushing defeat for the higher faculties and a lesson in intellectual humility, but he [Moore] had made a hell of a fight." At such a moment, Mr. Liebling's distrust of his divided audience becomes ironically transformed into distrust of himself and distrust of his subject. But these moments are fortunately rare.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

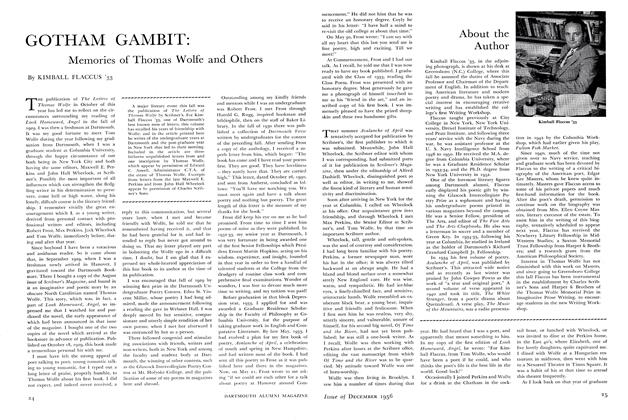

FeatureGOTHAM GAMBIT:

December 1956 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Feature

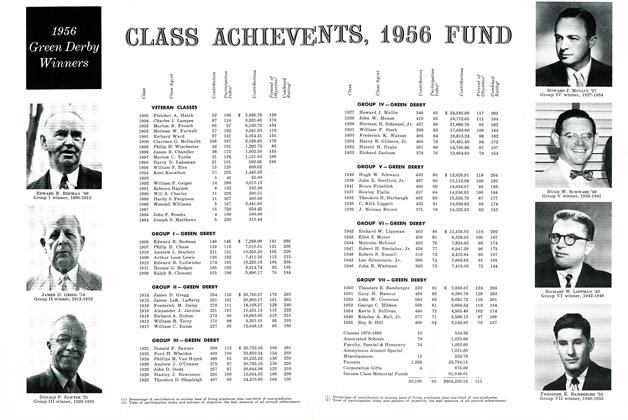

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVENTS, 1956 FUND

December 1956 -

Feature

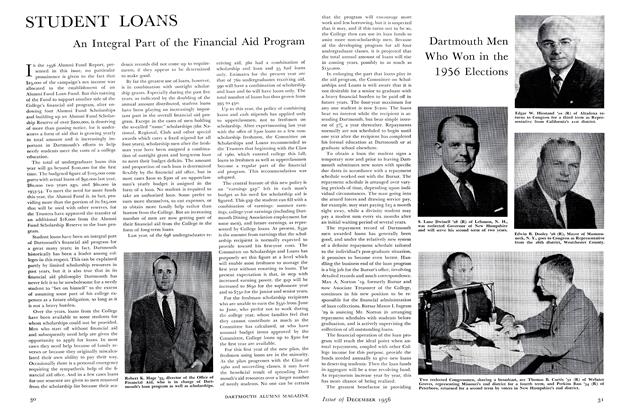

FeatureSTUDENT LOANS

December 1956 -

Feature

FeatureTHE 1956 ALUMNI FUND

December 1956 By William G. Morton '28 -

Feature

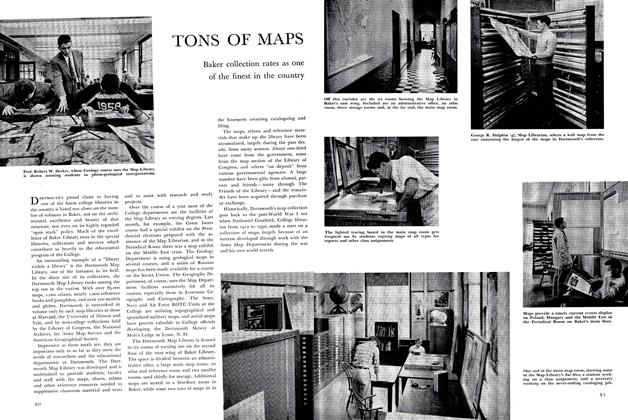

FeatureTONS OF MAPS

December 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

December 1956 By RICHARD C. CAHN, LT. (JG) EDWARD F. BOYLE, RICHARD CALKINS

Books

-

Books

BooksIn Christ's Own Country

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

June 1925 -

Books

BooksREFLECTIONS ON THE HUMAN VENTURE.

July 1960 By ALBERT H. HASTORF -

Books

BooksTHREE SOUTHWEST PLAYS, including WHERE THE DEAR ANTELOPE PLAY,

April 1942 By Benfield Pressey -

Books

BooksALEXANDER POPE'S EPISTLES TO SEVERAL PERSONS (MORAL ESSAYS).

MAY 1964 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE MIND OF CHINA

June 1933 By Robert A. McKennan