ByProf. Francois Denoeu. Boston: D. C. Heathand Company. 563 pp. $6.00.

The author's subtitle, "Anthologie-Histoire de la literature francaise des origines a nos jours," sums up exactly the viewpoint which animates his book. As an anthology which is also a history, it makes a constant effort to situate the texts which are presented. The student is led to see them as related to the plans of the works from which they are taken, to the education and experience of the writers, and to the ideas and tendencies of periods. For example, he may see in a ballade of Villon something of the Grand Testament, of a vagabond's career, and of fifteenth century lyricism. Or, if he is studying a selection from La Peste of Camus, he may grasp its connection with the rest of the story through a synopsis; he may link it as a myth with the ideas of an author who took an active part in the resistance; and he may follow in it some of the currents of recent intellectual life in France. Typographical aids make it easy to keep one's place in these varying perspectives. The thoroughness of the introduction to each text is matched by the richness of the annotation - linguistic, geographical, historical, literary as the occasion requires - which accompanies it. The author makes a special attempt to make French-things, people and values accessible to American students by cross-references to American life and literature.

I was impressed by the number and variety of the authors and selections, and by the effort to include not only the standard but also the out-of-the-ordinary: among the selections from Hugo are some one rarely sees in an anthology; Madame de La Fayette, whose psychological analyses are often considered too elaborate and too quaint for undergraduate reading, has her place in this collection, and other instances could be cited. It is worthy of note that, in a book which starts with the ninth century "Serments de Strasbourg," the earliest of "French" texts, and which aims to be reasonably complete in coverage, Professor Denoeu has given us, nevertheless, a liberal introduction to twentieth century authors (they take up approximately one-fourth of his space). And he lightens the effect of his academic virtues by the personal tone and the touches of humor which he works into his commentaries.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThirty Years After

June 1957 By RICHARD W. HUSBAND '26, -

Feature

FeatureAssignment: Antarctica

June 1957 By DON GUY '38, -

Feature

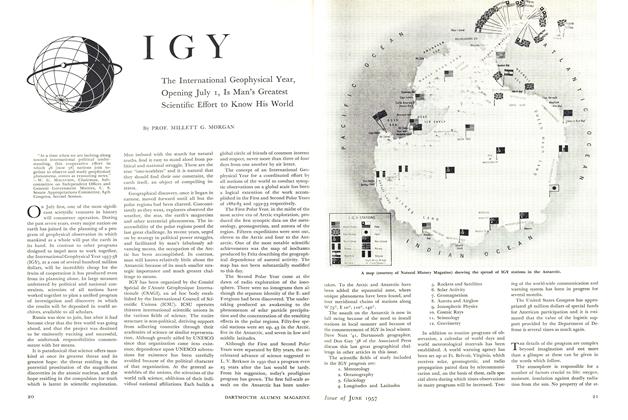

FeatureIGY

June 1957 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN -

Feature

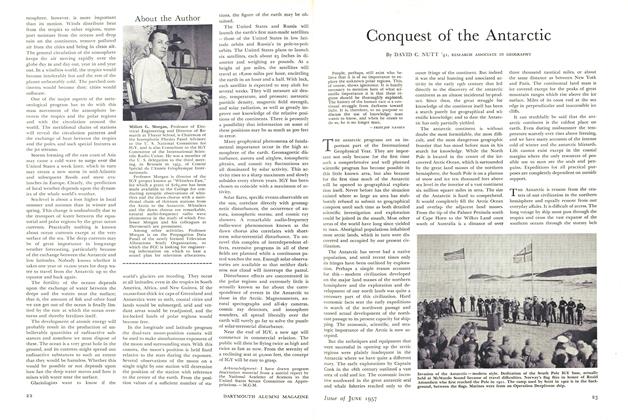

FeatureConquest of the Antarctic

June 1957 By DAVID C. NUTT '41, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

June 1957 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, FREDERICK K. WATSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1957 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR

Books

-

Books

BooksWOMEN, WOMEN, EVERYWHERE.

MAY 1964 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP II '42 -

Books

BooksTHE MAIN STREAM OF FRENCH LITERATURE.

December 1932 By Charles R. Bagley -

Books

BooksTHE FEDERAL BULLDOZER – A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF URBAN RENEWAL, 1949-1962.

FEBRUARY 1965 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Books

BooksJOHN JAY, FOUNDER OF A STATE AND NATION.

MARCH 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksWhat Went Awry in Miami

May 1975 By ROBERT K. CARR '29 -

Books

BooksTIME OF YEAR

April 1944 By Stearns Morse