Guest editor of the "UndergraduateChair" this month is Senior Fellow Samuel G. Smith '58 from Woodbury, Conn.,who gives his views on the academic lifeof the College. He is chairman of the Undergraduate Council's Academic Committee, president of Dragon, and a memberof Delta Tau Delta.

FROM a superficial point of view a description of the academic life of a college by one of its students would seem to be a rather innocuous waste of time. Fraternities, sports and general social life have so many facets that description of them is literally endless. But what can a student say of the academic life of the College? He goes to classes from 8 to 12, also one or two afternoons a week if he is a science major, and does a few hours' work in the evening in preparation for the next day's classes. That is as far as description can go superficially, but looking deeper there is a great deal more.

Perhaps the phrase that is most familiar to the undergraduate body, familiar because of its repetition, is President Dickey's advice that "here at Dartmouth the student has the chance of developing maturity by being given the opportunity to act immaturely." The undergraduate has applied this advice primarily to his social life, but he usually doesn't realize that it has direct application to his academic life as well. This, to me, is the uniqueness and advantage of a Dartmouth education. With a minimum of effort, the student can attain what is affectionately referred to as a "gentleman's average," a C average. This is not critical of the men who work hard to achieve such an average. Nor is it to say that Dartmouth does not adequately educate a man who attains a "gentleman's average." It simply points out one of the factors of the Dartmouth educational process: a man can receive the kind of education he wants.

The most basic area of independent study is in the honors programs of the various departments. Each department offers such a program and although the prospective honors student must have demonstrated certain qualifications before applying for this work, he does not have to be an exceptionally brilliant, straight-A student to be permitted to participate in the program. English honors is a rather typical honors program. The honors students are split into groups of three or four and are assigned to a professor, referred to as their tutor. Areas of reading are assigned and suggested, and a weekly paper is read and discussed at a weekly meeting of the tutorial group. Of course, much depends on the particular professor and the fellow students with whom an honors student is associated, as the success of the program centers not so much in the production of a weekly paper as it does in the interchange of ideas and concepts, fostered in the atmosphere of such a small, informal group.

The opportunities for an independent educational experience are amply provided; but it is disheartening to see the sparse advantage taken of them. It is difficult to say why the numbers of students in the honors programs are as small as they are. The admission requirements certainly are not so stiff that greater participation is prohibitive. Perhaps the philosophy of the "gentleman's average" is a contributing factor, although the work involved in the various honors programs is not that much more difficult, and it is certainly more interesting than the sometimes dull routine of classroom education. Perhaps a lack of proper publicity is to blame. Whatever the case, the College obviously sees the advantages of these programs, for with the advent of the new three-course, three-term curriculum, not only will the honors programs be expanded, but the philosophy underlying the whole curriculum will be pointing more towards self-education.

In 1929, President Hopkins voiced the belief that an ever-present and unconscious tendency of academic institutions is to view their students too much in the light of potential professional scholars and teachers. He felt that the curricula, scholarships and prizes were provided too much to meet that end. A program was therefore established, by his recommendation, to provide mature, dedicated students with the opportunity to spend an entire academic year in independent study in any field of their choosing in lieu of regular class work. In its original conception, President Hopkins felt that once a man was carefully chosen, he was free to do whatever he liked, nothing at all if that was his desire. The program met with both natural opposition and surprising support by the faculty, but in spite of the former it was established, and in 1929 the first Senior Fellowships were awarded.

The program continued until 1942 when the advent of the war necessitated its suspension. In 1946 the possibility of renewing the program was considered by President Dickey and he established a committee to investigate this. The committee sent letters to all the faculty and all former Senior Fellows asking for their candid opinions as to the value of re-establishing the program. Again opinions ran from emphatic denunciation to enthusiastic approval. The main criticism was not against the educational value of the program, but rather against its lack of supervision. Criticism from former fellows more than hinted at the flagrant misuses of the program; men were free, many felt, not for an intellectual pursuit, but rather for an extracurricular one. The BMOC applied for a Fellowship, not the serious student.

But again, in spite of damning denunciations, the program was re-established in 1947- Realizing that the criticisms were valid, the College this time established machinery whereby the freedom of the program would be retained, but retained under closer supervision. The Fellows were to be chosen more carefully by the criteria of "intellectual caliber, independence of character, and imaginative curiosity," and the particular topic that was to be the basis of their study. But most important, once a Fellow was appointed by the President of the College, he was to work with some member of the faculty, or some expert in his chosen field, who would both supervise and advise the Fellow in his work.

That is the way the Senior Fellowship program functions today. There are eleven of us, all working in different areas from political history and military organization to representative philosophical thought and the study of the relation of religion and medicine. We meet as a group every morning for coffee and conversation with various members of the faculty. And to keep more fully in touch with each other's work, preliminary reports have been presented to the entire group by each of the Fellows. There has been one rather exciting addition to the program this year. In the past, final reports of the year's work were presented to the present and succeeding Senior Fellow groups, but since the Fellows have become somewhat expert in their fields, it was necessary for them to talk down to their relatively novice Fellows. This year, however, informal meetings are to be arranged at which the Fellow will lead a discussion with experts and students interested in his particular specialty.

The advantage of self-education in these programs overwhelmingly outweighs any disadvantage pertaining to a limited proficiency. The new three-course, three-term curriculum, it seems to me, strikes the happy medium of an overall proficiency attained through self-education. The future of a Dartmouth education looks very bright. The excellent resources of Baker Library and the experience and wisdom of the faculty are being coordinated so that the initiative will originate where it belongs. Dartmouth will not hand a man an education; the man must earn an education from her.

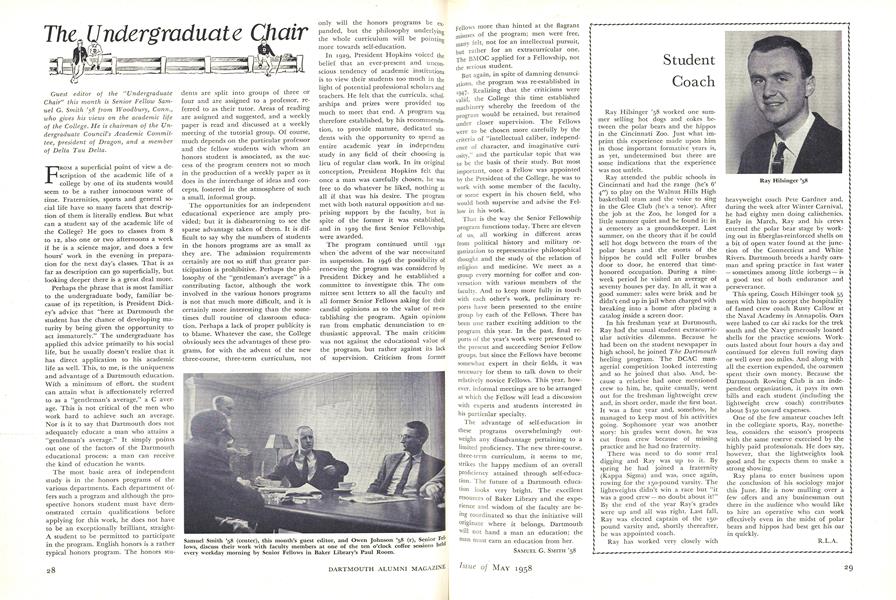

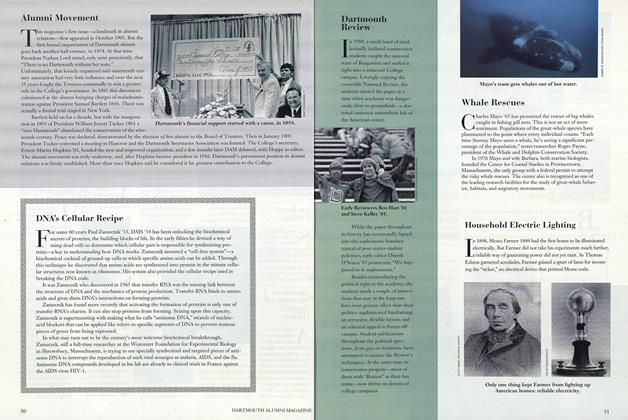

Samuel Smith '58 (center), this month's guest editor, and Owen Johnson '58 (r), Senior Fellows, discuss their work with faculty members at one of the ten o'clock coffee sessions held every weekday morning by Senior Fellows in Baker Library's Paul Room.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThree Civil War Letters

May 1958 By WILLIAM D. HARTLEY '58 -

Feature

FeatureChronicler of Gettysburg

May 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureENGINEERING SCIENCE

May 1958 -

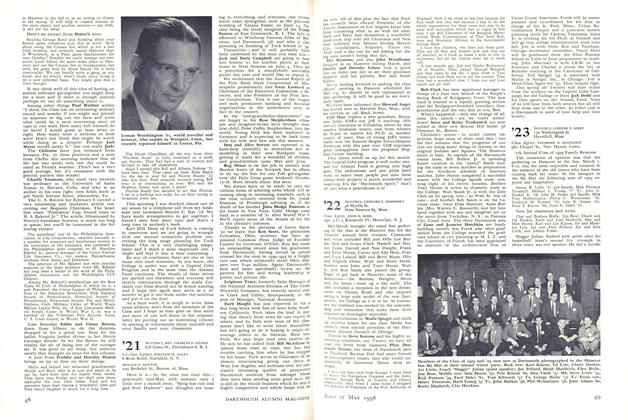

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1958 By CHESTER T. BIXBY, THEODORE D. SHAPLEIGH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleWhat Is "New" in the Program?

May 1958 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28