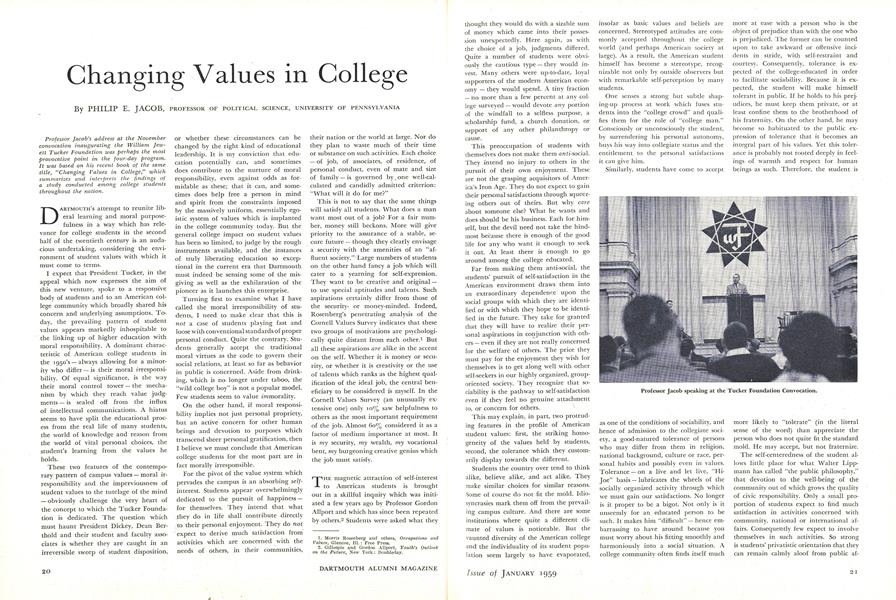

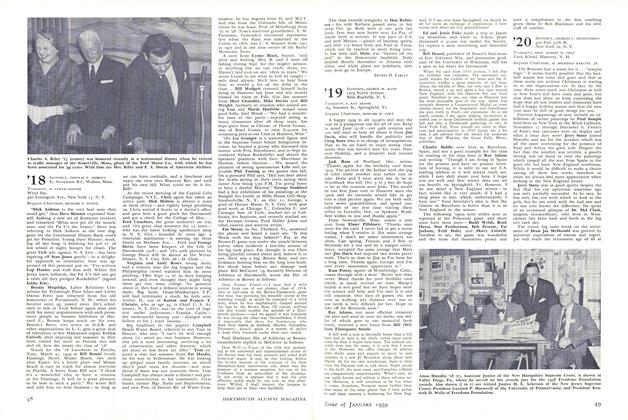

Professor Jacob's address at the Novemberconvocation inaugurating the William Jewett Tucker Foundation was perhaps the mostprovocative point in the four-day program.It was based on his recent book of the sametitle, "Changing Values in College," whichsummarizes and interprets the findings ofa study conducted among college studentsthroughout the nation.

PROFESSOR OF POLITICAL SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

DARTMOUTH'S attempt to reunite liberal learning and moral purposefulness in a way which has relevance for college students in the second half of the twentieth century is an audacious undertaking, considering the environment of student values with which it must come to terms.

I expect that President Tucker, in the appeal which now expresses the aim of this new venture, spoke to a responsive body of students and to an American college community which broadly shared his concern and underlying assumptions. Today, the prevailing pattern of student values appears markedly inhospitable to the linking up of higher education with moral responsibility. A dominant characteristic of American college students in the 1950's - always allowing for a minority who differ - is their moral irresponsibility. Of equal significance, is the way their moral control tower - the mechanism by which they reach value judgments — is sealed off from the influx of intellectual communications. A hiatus seems to have split the educational process from the real life of many students, the world of knowledge and reason from the world of vital personal choices, the student's learning from the values he holds.

These two features of the contemporary pattern of campus values - moral irresponsibility and the imperviousness of student values to the tutelage of the mind - obviously challenge the very heart of the concept to which the Tucker Foundation is dedicated. The question which must haunt President Dickey, Dean Berthold and their student and faculty associates is whether they are caught in an irreversible sweep of student disposition, or whether these circumstances can be changed by the right kind of educational leadership. It is my conviction that education potentially can, and sometimes does contribute to the nurture of moral responsibility, even against odds as formidable as these; that it can, and sometimes does help free a person in mind and spirit from the constraints imposed by the massively uniform, essentially egoistic system of values which is implanted in the college community today. But the general college impact on student values has been so limited, to judge by the rough instruments available, and the instances of truly liberating education so exceptional in the current era that Dartmouth must indeed be sensing some of the misgiving as well as the exhilaration of the pioneer as it launches this enterprise.

Turning first to examine what I have called the moral irresponsibility of students, I need to make clear that this is not a case of students playing fast and loose with conventional standards of proper personal conduct. Quite the contrary. Students generally accept the traditional moral virtues as the code to govern their social relations, at least so far as behavior in public is concerned. Aside from drinking, which is no longer under taboo, the "wild college boy" is not a popular model. Few students seem to value immorality.

On the other hand, if moral responsibility implies not just personal propriety, but an active concern for other human beings and devotion to purposes which transcend sheer personal gratification, then I believe we must conclude that American college students for the most part are in fact morally irresponsible.

For the pivot of the value system which pervades the campus is an absorbing self-interest. Students appear overwhelmingly dedicated to the pursuit of happiness - for themselves. They intend that what they do in life shall contribute directly to their personal enjoyment. They do not expect to derive much satisfaction from activities which are concerned with the needs of others, in their communities, their nation or the world at large. Nor do they plan to waste much of their time or substance on such activities. Each choice — of job, of associates, of residence, of personal conduct, even of mate and size of family - is governed by, one well-calculated and candidly admitted criterion: "What will it do for me?"

This is not to say that the same things will satisfy all students. What does a man want most out of a job? For a fair number, money still beckons. More will give priority to the assurance of a stable, secure future - though they clearly envisage a security with the amenities of an "affluent society." Large numbers of students on the other hand fancy a job which will cater to a yearning for self-expression. They want to be creative and original - to use special aptitudes and talents. Such aspirations certainly differ from those of the security- or money-minded. Indeed, Rosenberg's penetrating analysis of the Cornell Values Survey indicates that these two groups of motivations are psychologically quite distant from each other.l But all these aspirations are alike in the accent on the self. Whether it is money or security, or whether it is creativity or the use of talents which ranks as the highest qualification of the ideal job, the central beneficiary to be considered is myself. In the Cornell Values Survey (an unusually extensive one) only 10% saw helpfulness to others as the most important requirement of the job. Almost 60% considered it as a factor of medium importance at most. It is my security, my wealth, my vocational bent, my burgeoning creative genius which the job must satisfy.

THE magnetic attraction of self-interest to American students is brought out in a skillful inquiry which was initiated a few years ago by Professor Gordon Allport and which has since been repeated by others.2 Students were asked what they thought they would do with a sizable sum of money which came into their possession unexpectedly. Here again, as with the choice of a job, judgments differed. Quite a number of students were obviously the cautious type - they would invest. Many others were up-to-date, loyal supporters of the modern American economy - they would spend. A tiny fraction - no more than a few percent at any college surveyed - would devote any portion of the windfall to a selfless purpose, a scholarship fund, a church donation, or support of any other philanthropy or cause.

This preoccupation of students with themselves does not make them anti-social. They intend no injury to others in the pursuit of their own enjoyment. These are not the grasping acquisitors of America's Iron Age. They do not expect to gain their personal satisfactions through squeezing others out of theirs. But why care about someone else? What he wants and does should be his business. Each for himself, but the devil need not take the hindmost because there is enough of the good life for any who want it enough to seek it out. At least there is enough to go around among the college educated.

Far from making them anti-social, the students' pursuit of self-satisfaction in the American environment draws them into an extraordinary dependence upon the social groups with which they are identified or with which they hope to be identified in the future. They take for granted that they will have to realize their personal aspirations in conjunction with others even if they are not really concerned for the welfare of others. The price they must pay for the enjoyment they wish for themselves is to get along well with other self-seekers in our highly organized, group-oriented society. They recognize that sociability is the pathway to self-satisfaction even if they feel no genuine attachment to, or concern for others.

This may explain, in part, two protruding features in the profile of American student values: first, the striking homogeneity of the values held by students, second, the tolerance which they customarily display towards the different.

Students the country over tend to think alike, believe alike, and act alike. They make similar choices for similar reasons. Some of course do not fit the mold. Idio-syncrasies mark them off from the prevailing campus culture. And there are some institutions where quite a different climate of values is noticeable. But the vaunted diversity of the American college and the individuality of its student population seem largely to have evaporated, insofar as basic values and beliefs are concerned. Stereotyped attitudes are commonly accepted throughout the college world (and perhaps American society at large). As a result, the American student himself has become a stereotype, recognizable not only by outside observers but with remarkable self-perception by many students.

One senses a strong dut subtle shaping-up process at work which fuses students into tke "college crowd" and qualifies them for the role of "college man." Consciously or unconsciously the student, by surrendering his personal Autonomy, buys his way into collegiate status and the entitlement to the personal satisfactions it can give him.

Similarly, students have come to accept as one of the conditions of sociability, and hence of admission to the collegiate society, a good-natured tolerance of persons who may differ from them in religion, national background, culture or race, personal habits and possibly even in values. Tolerance — on a live and let live, "HiJoe" basis - lubricates the wheels of the socially organized activity through which we must gain our satisfactions. No longer is it proper to be a bigot. Not only is it unseemly for an educated person to be such. It makes him "difficult" - hence embarrassing to have around because you must worry about his fitting smoothly and harmoniously into a social situation. A college community often finds itself much more at ease with a person who is the object of prejudice than with the one who is prejudiced. The former can be counted upon to take awkward or offensive incidents in stride, with self-restraint and courtesy. Consequently, tolerance is expected of the college-educated in order to facilitate sociability. Because it is expected, the student will make himself tolerant in public. If he holds to his prejudices, he must keep them private, or at least confine them to the brotherhood of his fraternity. On the other hand, he may become so habituated to the public expression of tolerance that it becomes an integral part of his values. Yet this tolerance is probably not rooted deeply in feelings of warmth and respect for human beings as such. Therefore, the student is more likely to "tolerate" (in the literal sense of the word) than appreciate the person who does not quite fit the standard mold. He may accept, but not fraternize.

The self-centeredness of the student allows little place for what Walter Lippmann has called "the public philosophy," that devotion to the well-being of the community out of which grows the quality of civic responsibility. Only a small proportion of students expect to find much satisfaction in activities concerned with community, national or international affairs. Consequently few expect to involve themselves in such activities. So strong is students' privatistic orientation that they can remain calmly aloof from public affairs even when they acknowledge a pessimistic view of the public destiny. For instance, a good majority in relevant inquiries confidently predict a major war within their lifetime, many anticipating its onset soon. But they do not therefore bestir themselves to prevent it; nor do they allow a mood of alarm to intrude upon their pursuit of personal happiness. Some observers are convinced that this ambivalence reflects maturity and sophistication, students refusing to reshape the conduct of their lives and reorder the priorities of their values in the face of prospective events they are sure they are powerless to alter. It seems more likely that many students have so isolated themselves in the compartment of their private interests, that they are actually illiterate about the world outside, and have no basis for sound judgment as to what they might or might not accomplish if they did strike out to affect public policy. They know too little to be sophisticated. They care too little to be mature.

ONE aspect of the broad pattern of student values at first look seems to offset, if not actually contradict the impression of moral irresponsibility. This is the very widespread acceptance of religious belief and practice, often heralded as the "religious revolution on the campus." The great majority of students acknowledge forthrightly a need for religion in their lives, testify to a personal belief in divine influence (even if they do not all sense God as a personal presence) and regularly attend religious service.

However, one cannot help wondering how fundamental is this religious dimension in students' lives, and how vital an imperative towards moral responsibility it provides. Religious interest does not fare well when put into competition with the secular values of students. They do not consider religious activity as one of the areas which will command an important share of their future attention and they do not expect it will yield much personal satisfaction. Rarely do students seem to relate religious belief to important personal choices, such as their vocation, the human relations policies of the groups to which they belong, or the disposition of their financial resources. Nor do they link religious belief with social, economic or political judgments. Moral law — if admitted to exist - is not made relevant to group behavior or public policy.

It is not necessary to question the genuineness of student religion to conclude that it may affect only a small segment of a student's life - that it may place among his values (perhaps rather well down the scale) instead of being the central force in his life around which all values orbit. Many students may actually consider religion no more than a phase of the social sector of life, one of the acceptable areas of association through which to conduct the procurement of their essentially secular satisfactions. The enthusiastic comment of one sponsor of student religious life, to the effect that "it is now the thing to do for a man to take his girl to church" reveals just how shallow a foundation may be supporting the edifice of student religiosity.

We should not leave the assessment of students' moral outlook without recalling again the almost universal respect in which are held the personal moral virtues of honesty, sincerity, loyalty, friendship and propriety in relations between the sexes. As noted earlier, these are virtually unchallenged, in the abstract, as ethical standards by which students should regulate personal conduct. Personal morality and personal enjoyment are not opposed to each other, most students would feel. On the contrary, they expect virtue and pleasure to go hand in hand - in a kind of modernized version of the Puritan conviction that if one works hard and believes in God one will reap material rewards in this world as well as spiritual recompense later. (Today's students tend to be less concerned with the returns in the hereafter if they can find the key to happiness in the here and now.)

But what if, in concrete situations, virtue rises up to block the road to happiness? Students are then usually prepared to temper the moral code to meet the exigencies of self-interest. They do this without much agony of soul or self-condemnation. When one's own immediate interest is at stake, a little cheating, a little harmless lying, a little sacrifice of friendly loyalties may be condoned. Also, the dictates of sociability will not permit the moral code to be used to censure those who may choose to indulge in errant behavior. Tolerance takes precedence over prudery when it comes to judging the conduct of others.

This then is the picture - in very broad strokes — of those values which dispose students toward moral irresponsibility - that is, the avoidance o£ concern or action on behalf of anyone but oneself and one's immediate family. The picture is of course a composite, a portrayal of features characteristic of the mass. It does not accurately describe any particular student. Nor does it apply even in a general way to all students. Individuals differ in many respects, and a sizable number of students hold values so different from those described that no one could recognize them in the composite. Many of these deviators from the norm, these individuals who do not conform to the student stereotype, are potential recruits for a venture in the development of moral responsibility. Some are already at the forefront of responsible student leadership. Some are caught in a tangle of inward tensions which block creative effort. They are a lonely minority, often tagged with the label of "odd-ball." The mark of their oddness is more likely than not to be their readiness to join causes and otherwise to demonstrate interests beyond themselves. The fact that such are identified as the odd ones simply confirms what is the prevailing pattern.

Against the pattern of moral irresponsibility, liberal education has been making little headway. The basic values of most college students do not change much during their four years of instruction, be it vocationally oriented or humanistically inspired. In institution after institution, seniors reflect the essential attitudes, prejudices and beliefs of the entering freshmen. Here and there the senior emerges as a man or woman capable of greater consistency in the articulation of his values, and more skillful in the adjustment of his values to the circumstances in which he intends to function and achieve his satisfactions. Some seniors are more flexible and more suave personalities than when they began college. On the other hand, a few are more troubled, more doubting, more independent in their judgments, more conscious of themselves as individuals and more sensitive to others. But for the most part, the values held by students show but little effect of exposure in college to the insights of humanistic teaching and the demonstrations of rational and scientific inquiry. One rarely detects, either by objective checking or in the personal reflections of students, the mark of a course or even of a teacher.

Yet the evidence mounts that students take their college education seriously. On the whole, they hold in esteem higher education in general and their own college in particular. And the study just completed by Professor Max Wise for the American Council on Education indicates that students today are probably outperforming preceding generations in intellectual achievement.3 However, the worthy accomplishments of the mind just do not carry over to affect the attitudes students hold and the important decisions they make. Knowledge grows but values remain the same. Education tools up the student for his vocational run. It assures him the extra $100,000 or more which a college degree is held to earn him in a lifetime. And it entitles him to all the other privileges and perquisites pertaining thereto. But it does not make him a more morally responsible person.

What seems to have happened is a subtle splitting apart of the intellectual from the moral life of the student. Or perhaps it should be viewed as a failure to draw together in a meaningful integration, the resources of mind and the sources of values which never were well knit in the student's earlier years. However the hiatus is interpreted and whatever may have been the contributing factors to its establishment, an educator should realize that he is probably communicating with his students on only one level. He may feel good rapport with the students and they with him. But the odds are strongly against his entering the forum in which the fashioning of values occurs. This is a sanctuary, not entirely private, for other students frequently cross its threshold to add a bit or chip away on a value. But its door is usually closed to professors; and students are apparently able to close it also to the probings of their own rational processes. Many students are evidently sophisticated enough to operate their lives on two planes simultaneously, the rational and the moral, avoiding collisions by making sure that no crossovers occur.

IF THESE are reasonably accurate reflections on the contemporary pattern of student values, how can the Tucker Foundation meet its self-imposed test of "relevance" to the students and to their world? Is the objective of "education for moral responsibility" Utopian, considering the students' irresponsibility and the current impotency of most college education to change values?

The case hinges, I believe, upon whether the lack of impact of the educational process upon values stems at least partially from conditions in our colleges which can be changed if we want to. There is some basis for considering that it does. Students' values do change markedly in certain colleges of peculiar potency, often in directions quite at variance with the rest of the college world. We might presume that what is possible in some places ought to be possible elsewhere. But we know little about the factors which really account for the potency where it appears, and we certainly cannot be sure that they can be effectively duplicated outside the original habitat. A new venture in educating for moral responsibility must necessarily be largely experimental.

Contrasting some of the apparently potent colleges with those which have had little general impact upon values, certain characteristic conditions of impotency emerge. 1. The general atmosphere is impersonal. Students are left largely uncertain as to what is expected of them outside of settling into established routines of class attendance and extracurricular activities. 2. The pattern of education is rather uniform and standardized, with little incentive to students to launch out on explorations of their own and little opportunity for experiences which would sharply challenge their presumptions and ideas. 3. The faculty is largely disinterested in students, preoccupied with their own professional business. Many conceive of their educational function as the bare communication of knowledge rather than an "enlightenment" in its broad, humanistic sense. 4. The campus is dominated unchallenged by student cultural "dictators" - traditions, social organizations, unwritten codes of conduct - which press students to conform their habits and ways of thought to a prescribed pattern and to avoid independent judgment and action.

The potent college on the other hand tends to have a distinctive atmosphere which is quickly obvious to even a casual visitor. It is characterized by a "community of values" which is shared by faculty and students alike. All are conscious of certain expectations of the student who will graduate. There are usually close relationships between many students and many faculty, and communication flows easily among them. Nearly everyone feels associated in an important common enterprise of worth both to the individual and to the community as a whole.

There is a danger that such a college may achieve potency in the influencing of student values at the sacrifice of true intellectual and moral freedom. In other words, it may so "rig" the level of expectancy for its students that it establishes what may be described as a closed community of values. There is evidence that this kind of an approach may have a really substantial impact upon students' values. Following this model, we might reasonably aspire to the renewal of monastic havens for the ideal of the good life, to the nurture of moral responsibility in seclusion from the amoral society which now surrounds us.

But I take it that this is alien to the objectives of the Tucker Foundation, which looks to the growth of moral responsibility in association with the pursuit of free inquiry and to the active influence of the morally responsible in the secular society.

Can one expect that liberal education in an open community of values - one where values differ and no one pattern is held up as orthodox - will be at all influential? Here and there, this seems indeed to be happening, but the vital elements in the liberating process are not yet isolated.

The potency of liberal education does appear to depend in large degree upon its relevancy to the individual student and to the value-generating experiences in his life.

Second, where a student's values can be exposed to conflict and tested in concrete situations of human relations and civic responsibility, they can be changed - or confirmed. In any case, the student becomes more personally responsible for the values he holds. They are then his, not someone else's.

Discord is evidently another important element in potent liberal education. Students, when confronted with divergent values, may find the roots of their own values so challenged that they shake loose from complacent acceptance of the traditional, the authoritative or the socially certified values.

At this point, whatever its program or techniques, the college which seeks to become a liberating power, has a critical task to perform. It must identify and sensitively assist the student who is on the verge of breaking out of the vise of values which has gripped him, be they values which the college honors or abhors. For out of the discord, the student reaches for individual autonomy. And from this autonomy, with proper encouragement, may grow the full moral responsibility for which we aspire.

1. Morris Rosenberg and others, Occupations and Values. Glencoe. III.: Free Press.

2. Gillespie and Gordon Allport, Youth's Outlook on the Future, New York : Doubleday.

3. "They Gome For the Best of Reasons," Washington, D, C.: American Council on Education.

Professor Jacob speaking at the Tucker Foundation Convocation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNorth Country Citizen

January 1959 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureThe Outward Look

January 1959 By BEVAN M. FRENCH '58 -

Article

Article"What Does the Tucker Foundation Do?"

January 1959 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE1 more ... -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

January 1959 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, RUSSELL J. RICE, G. KELLOGG ROSE JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

January 1959 By STANTON B. PRIDDY, DR. ROBFRT L. CRAIG

Features

-

Feature

FeatureContemporary Man

DECEMBER 1966 -

Feature

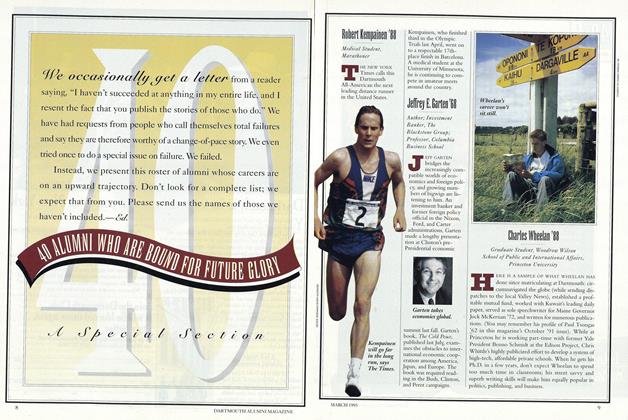

FeatureHomage to the great god Pigskin: One hundred years of Ivy rivalry

OCTOBER 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJeffrey E. Garten '68

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GET YOUR NAME INTO THE GUINNESS BOOK OF WORLD RECORDS

Jan/Feb 2009 By LARRY OLMSTED, MALS '06 -

Feature

FeatureONE HUNDRED MASTER DRAWINGS

October 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40