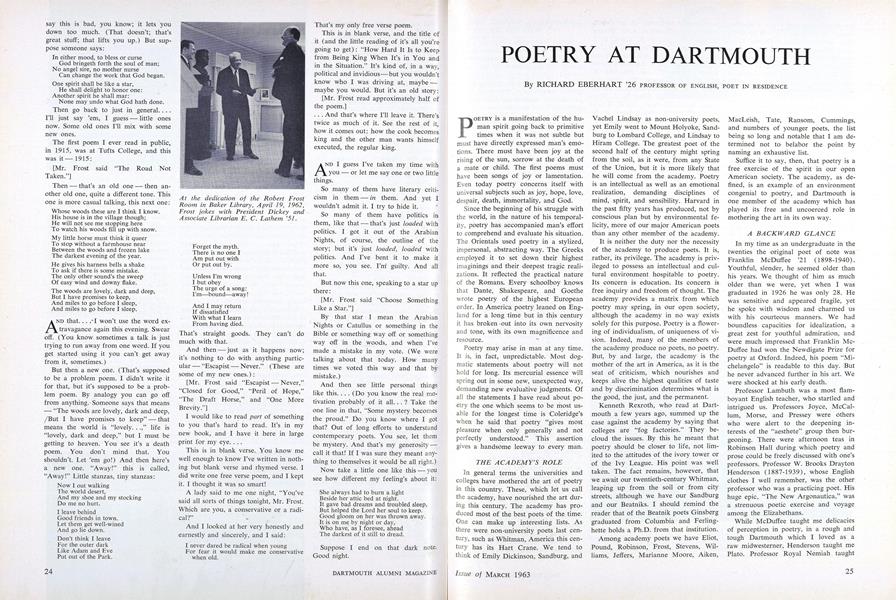

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH, POET IN RESIDENCE

POETRY is a manifestation of the human spirit going back to primitive times when it was not subtle but must have directly expressed man's emotions. There must have been joy at the rising of the sun, sorrow at the death of a mate or child. The first poems must have been songs of joy or lamentation. Even today poetry concerns itself with universal subjects such as joy, hope, love, despair, death, immortality, and God.

Since the beginning of his struggle with the world, in the nature of his temporality, poetry has accompanied man's effort to comprehend and evaluate his situation. The Orientals used poetry in a stylized, impersonal, abstracting way. The Greeks employed it to set down their highest imaginings and their deepest tragic realizations. It reflected the practical nature of the Romans. Every schoolboy knows that Dante, Shakespeare, and Goethe wrote poetry of the highest European order. In America poetry leaned on England for a long time but in this century it has broken out into its own nervosity and tone, with its own magnificence and resource.

Poetry may arise in man at any time. It is, in fact, unpredictable. Most dogmatic statements about poetry will not hold for long. Its mercurial essence will spring out in some new, unexpected way, demanding new evaluative judgments. Of all the statements I have read about poetry the one which seems to be most usable for the longest time is Coleridge's when he said that poetry "gives most pleasure when only generally and not perfectly understood." This assertion gives a handsome leeway to every man.

THE ACADEMY'S ROLE

In general terms the universities and colleges have mothered the art of poetry in this country. These, which let us call the academy, have nourished the art during this century. The academy has produced most of the best poets of the time. One can make up interesting lists. As there were non-university poets last century, such as Whitman, America this century has its Hart Crane. We tend to think of Emily Dickinson, Sandburg, and Vachel Lindsay as non-university poets, yet Emily went to Mount Holyoke, Sandburg to Lombard College, and Lindsay to Hiram College. The greatest poet of the second half of the century might spring from the soil, as it were, from any State of the Union, but it is more likely that he will come from the academy. Poetry is an intellectual as well as an emotional realization, demanding disciplines of mind, spirit, and sensibility. Harvard in the past fifty years has produced, not by conscious plan but by environmental felicity, more of our major American poets than any other member of the academy.

It is neither the duty nor the necessity of the academy to produce poets. It is, rather, its privilege. The academy is privileged to possess an intellectual and cultural environment hospitable to poetry. Its concern is education. Its concern is free inquiry and freedom of thought. The academy provides a matrix from which poetry may spring, in our open society, although the academy in no way exists solely for this purpose. Poetry is a flowering of individualism, of uniqueness of vision. Indeed, many of the members of the academy produce no poets, no poetry. But, by and large, the academy is the mother of the art in America, as it is the seat of criticism, which nourishes and keeps alive the highest qualities of taste and by discrimination determines what is the good, the just, and the permanent.

Kenneth Rexroth, who read at Dartmouth a few years ago, summed up the case against the academy by saying that colleges are "fog factories." They becloud the issues. By this he meant that poetry should be closer to life, not limited to the attitudes of the ivory tower or of the Ivy League. His point was well taken. The fact remains, however, that we await our twentieth-century Whitman, leaping up from the soil or from city streets, although we have our Sandburg and our Beatniks. I should remind the reader that of the Beatnik poets Ginsberg graduated from Columbia and Ferlinghette holds a Ph.D. from that institution.

Among academy poets we have Eliot, Pound, Robinson, Frost, Stevens, Williams, Jeffers, Marianne Moore, Aiken, MacLeish, Tate, Ransom, Cummings, and numbers of younger poets, the list being so long and notable that I am determined not to belabor the point by naming an exhaustive list.

Suffice it to say, then, that poetry is a free exercise of the spirit in our open American society. The academy, as defined, is an example of an environment congenial to poetry, and Dartmouth is one member of the academy which has played its free and uncoerced role in mothering the art in its own way.

A BACKWARD GLANCE

In my time as an undergraduate in the twenties the original poet of note was Franklin McDuffee '2l (1898-1940). Youthful, slender, he seemed older than his years. We thought of him as much older than we were, yet when I was graduated in 1926 he was only 28. He was sensitive and appeared fragile, yet he spoke with wisdom and charmed us with his courteous manners. We had boundless capacities for idealization, a great zest for youthful admiration, and were much impressed that Franklin McDuffee had won the Newdigate Prize for poetry at Oxford. Indeed, his poem "Michelangelo" is readable to this day. But he never advanced further in his art. We were shocked at his early death.

Professor Lambuth was a most flamboyant English teacher, who startled and intrigued us. Professors Joyce, McCallum, Morse, and Pressey were others who were alert to the deepening interests of the "aesthete" group then burgeoning. There were afternoon teas in Robinson Hall during which poetry and prose could be freely discussed with one's professors. Professor W. Brooks Drayton Henderson (1887-1939), whose English clothes I well remember, was the other professor who was a practicing poet. His huge epic, "The New Argonautica," was a strenuous poetic exercise and voyage among the Elizabethans.

While McDuffee taught me delicacies of perception in poetry, in a rough and tough Dartmouth which I loved as a raw midwesterner, Henderson taught me Plato. Professor Royal Nemiah taught me Greek. Although I was a middling student, he gave me a vision of the Greek spirit which has lasted a lifetime. To all these professors, with especially warm memories of W. K. Stewart, I owe a debt of gratitude not sufficiently paid in words so few as these. And to Ruby Daggett of the Bookstore, who secured for us the latest avant-garde books.

THE ARTS ANTHOLOGY

We published the literary magazine of the time, The Tower, with much enthusiasm but perhaps the monument of the decade is a small volume of 57 pages, handsomely printed by The Mosher Press in Portland, Maine, June 1925, entitled "The Arts Anthology / Dartmouth Verse 1925/ With Introduction /by Robert Frost."

Mr. Frost employed a figure of "a waterspout at sea," to which, I believe, he never returned, yet his ideas are worth quoting. The poet "has to begin as a cloud of all the other poets he ever read. That can't be helped. And first the cloud reaches down toward the water from above and then the water reaches up toward the cloud from below and finally cloud and water join together to roll as one pillar between heaven and earth. The base of water he picks up from below is of course all the life he ever lived outside of books."

A paragraph from the Foreword reads: "A board of judges, consisting of Professors David Lambuth, L. Dean Pearson, and Franklin McDuffee, of the Department of English, and of A. G. Dewing, A. C. C. Hill Jr., A. K. Laing, D. S. Slawson, and G. J. Winger, of the Class of 1925, divided The Arts Poetry Award between Richmond A. Lattimore for his poem "Threnody" and Marshall W. Schacht for his poem "The First Autumn." The poets represented in the anthology were H. E. Allen, W. A. Breyfogle, R. G. Eberhart, A. W. Edson, A. C. C. Hill Jr., Bravig Imbs, A. K. Laing, R. A. Lattimore, S. Lenke, Marshall W. Schacht, H. S. Talbot, P. B. Tanner, and C. D. Webster.

Perhaps it is appropriate here to reprint Marshall Schacht's "The First Autumn." He died in 1956 at 51 without exceeding the lyrical talent shown in this early poem. He published a fine book of poems, Fingerboard, in 1949.

THE FIRST AUTUMN

Where God had walked The goldenrod Sprang like fire From the burning sod.

The purple asters, When He spoke, Rose up beautifully Like smoke, And shouting glory To the sky, The maple trees Where He passed by!

But when God blessed The last bright hill The holy word Grew white and still.

THE THIRTIES, FORTIES, FIFTIES,AND INTO THE SIXTIES

Several Dartmouth alumni poets have favored us with recent examples of their work. These are set forth along with this article. We are grateful for the opportunity to publish new or recent poems by these poets. It is not my purpose to give critical estimations of their work but to provide brief summaries of their principal publications and main interests.

Alexander Laing '25 began with Hanover Poems, published jointly with Richmond Lattimore '26. Fool's Errand appeared in 1928, and Wine and Physic in 1934. Mr. Laing combines intellectual wit with sharp control of poetic structures. He is best known as a novelist and expert interpreter of whaling and sea life of the nineteenth century.

Richmond Lattimore '26 is equally well known as poet and one of America's best Greek scholars. Dartmouth conferred on him its honorary Doctorate of Letters in 1958. For many years he has taught Greek at Bryn Mawr. His Poems came out in 1957, winning critical praise. His newest book, Sestina for a Far-Off Summer, 1962, establishes him as a poet of marked power and ability. Between 1947 and the present he translated and published a large body of Greek work: Odesof Pindar, The Iliad of Homer, TheOresteia of Aeschylus, Greek Lyrics, and Hesiod. He also published The Poetry ofGreek Tragedy in 1958, and edited, with David Greene, The Complete GreekTragedies. His poetry has become more realistic and broader of scope since his undergraduate days. He is recognized as a poet with his own voice and style. He has recently written pastoral poems showing nostalgia for the old China where he was born.

Reuel Denney '32, well known as a sociologist, published The ConnecticutRiver in 1939. He next appeared as poet in 1957 with The Astonished Muse and published his newest book, In Praise ofAdam, in 1961. Denney's work has increased in skill and subtlety. He favors wit in fine modulations and intricacies of verbal relationships.

Kimball Flaccus '33, with a delicate poetic gift, published In Praise of Mara in 1932, Avalanche of April in 1934, and The White Stranger in 1940. This last book was a poetic version of the story of Quetzalcoatl inspired by the author's having, as an undergraduate, watched Orozco paint the murals in Baker Library.

Samuel French Morse '36 published Two Poems from the Baker Library in 1934 and The Yellow-Lilies from Baker in 1935. He published 5 CummingtonPoems in 1939. In 1955 his The ScatteredCauses appeared, since which time he has appeared with growing frequency in literary quarterlies. He is the literary executor of Wallace Stevens, has written fully on him, with further work to come. His poetry has a definite New England tang, asperity, and ring of truth.

Philip Booth '47 published Letter froma Distant Land in 1957, which won the Lamont Prize, followed by The Islanders, 1961, acclaimed for many excellent poems with a Maine setting. Booth has a strong grasp of reality from which he is able to loose splendid poems, well articulated and original, and is in our times the best poet of the sea.

Robert Pack '51 wrote a fine book on Wallace Stevens in 1958. In 1959 his first poems appeared, entitled A Stranger's Privilege, marked by profundity. Early this year his second book, Guardedby Women, showed again the depths and the well-wrought make of his insights.

THE CHARLES BUTCHER FUND

Since the academic year 1956-1957 The Butcher Foundation of the Butcher Polish Company of Boston has given annual sums of money to help poetry at Dartmouth. These gracious gifts have been well used principally in two ways, to bring to Dartmouth poets for readings and to publish volumes of undergraduate poetry.

In that first year Dartmouth enjoyed the young poet W. S. Merwin, who had recently been living abroad and who read from his new poems, which were well received.

We also had Dame Edith Sitwell here. There was considerable excitement at the prospect of her coming. As she is always rather grandly theatrical about the conditions of life, we wondered if she would make it up from New York by train. We received a wire asking us to meet her with a wheelchair. This threw everybody into dismay but we produced the wheelchair, which she did not have immediately to use. She walked with a cane. She complained that she had fallen in her palace in Italy and hurt her foot.

That evening I recall that Professor Elmer Harp and I each took her by an arm and escorted her laboriously up to the podium in 105 Dartmouth as a breathless audience watched her turbaned, bejeweled, and queen-like progress. Once she got into her magnificent poems, those paeans of praise to the Lord, after calling for water for a parched throat, one forgot any of her real or imagined infirmities and was taken by her masterful presentations.

We were again dismayed at her only method of egress from Hanover, which was by train from White River Junction at later than one in the morning. Despite careful planning when the train arrived there was no place for Dame Edith but a small cramped space unsuitable to her great frame. We hoped that loud protestations would alleviate the embarrassing situation before too many miles. It must be said that Dame Edith, descendant of Plantagenets, took it all with good grace.

1957-1958 opened with Barbara Howes and William Jay Smith, husband and wife, both accomplished poets, in a reading of their poems in the Tower, a pleasant literary occasion. John Ciardi came next, provocative and sprightly, honest and direct, who later returned to Dartmouth for a reading and again for a Great Issues lecture. He was followed by Kenneth Rexroth. Students were hanging from the rafters, so to speak, in the Tower Room. Rexroth, sometimes called the father of the San Francisco Beatnik school, but who disallowed the designation, appeared when the Beatniks were all the rage. He read his own poetry and played Chinese and Japanese poems which he had translated.

In 1958-1959 we enjoyed Robert Lowell, the leading poet of his generation. Robert Pack '51 read his deeply felt poems. W. D. Snodgrass, young winner of the Pulitzer Prize, enthused the audience with the cutting edge of his realistic poetry. Lastly, George Barker, in this country from England, stayed several days to visit classes in addition to his Tower reading, which included his new verse play "In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree." It was unusually hot by the time he arrived and Barker is the only Englishman I know who had the courage to take off his jacket and read in his shirtsleeves.

During 1959-1961, a young instructor in the English Department, Jack Hirschman (about to produce his first book of poems with an introduction by Karl Shapiro), stimulated interest in poetry by originating the so-called Babel readings. These were hour evening sessions in the library at Sanborn House devoted to foreign poetry with translations, poetry readings by undergraduates or older invited poets, and poetry said to jazz. These events were enthusiastically received and enjoyed. Paul Goodman gave a reading of his poetry while here to present a lecture.

In recent years the English Department and the Lecture Series also brought to the campus for readings or lectures such different poets as I. A. Richards, Robert Graves, Marianne Moore, and E. E. Cummings.

In 1961-1962 we had a reading of his thoughtful work by Stanley Kunitz, a Pulitzer Prize winner, who returned later to give the first lecture on poetry for Great Issues in the Spaulding Auditorium. Brother Antoninus came from California, appearing in the robes of his lay brotherhood, to astound the Babel audience by his confessional Christian poetry. Kathleen Raine, formerly of Girton College, Cambridge, on tour in this country, read, finally, her austere and elegant poems.

Thus far in 1962-1963 the first poetry readings given in the new Hopkins Center were presented last fall by Donald Hall and Robert Pack '5l, joint editors of the second edition of their anthology of poets under forty in Great Britain and America. The Top of the Hop proved to be a lively place for a poetry reading.

In addition to providing poets for readings, the Charles Butcher Fund has made possible the publication of volumes of undergraduate poetry. Some examples of undergraduate work from these books are set forth with this article.

THE THURSDAY POETS

For years a stable influence on poetry at Dartmouth has been The Thursday Poets, held each Thursday, beginning promptly at 4:15 p.m. in the Poetry Room at Baker and ending at 5:00, ably conducted by Alexander and Dilys Laing until the untimely death of Mrs. Laing in 1960. Since then Professor Laing has carried on alone, with the help of colleagues, notably Professors Ramon Guthrie and Thomas Vance. The serene yet penetrating influence of Dilys Laing will long be felt by all who knew her and her poetry.

The meetings afford workshops where undergraduate poets may receive criticism of their poems from peers and professors. Quite often there are sessions enlivened by an invited outside poet, by a poet who has come to Dartmouth to give a formal reading, by professors at the College who are also poets, or by poets from the town or surrounding communities. This informal institution serves the College in a valuable way. There are also, of course, regular courses in the curriculum where poetry is studied but not written, and there are creative writing classes in both prose and poetry, of which Professors Dewing and Laing teach the former and I teach the latter.

There are also sporadic undergraduate poetry magazines. During the last few years the titles have been The Dart, TheDartmouth Quarterly, Vox (published by The Dartmouth), and currently Greensleeves. These magazines have provided a medium for the publication of undergraduate poetry and for the expression of sometimes controversial ideas and opinions.

PROFESSOR POETS AND OTHERS

No account of poetry at Dartmouth would be complete without consideration of Dartmouth professors and others, not alumni, who are professional poets. The influence of their work is present in the community, notably enriching the poetical scene.

The work of Alexander Laing has been noted earlier. Dilys Laing published several volumes in earlier years, wrote much and splendidly in the last ten years of her life. Her most recent book, Poems froma Cage, is a posthumous one, about which I said, "She wrote poetry of modern sensibility, clear but warm, precise but imaginative." The current number of The Carleton Miscellany features her work with 27 new poems, with a commentary by Prof. Ramon Guthrie.

Ramon Guthrie, likewise with books to his credit, published Graffiti in 1959, which showed new skills and a great deal of humanity and wit.

Thomas Vance brought his writing of poetry to a striking first book, Skeletonof Light, published in 1961, which displayed the metaphysical enmeshed in the physical. Both Guthrie and Vance won critical acclaim.

Bink Noll, who wrote poetry while teaching at Dartmouth, last fall brought out his first book, marked by depth and an individual style, entitled The Centerof the Circle. He is now teaching at Beloit. Another former teacher, Frederic Will, published A Wedge of Words in 1962. He teaches at the University of Texas. His book was dedicated to Dilys Laing, who shared a dedication in Mr. Noll's book.

GROUP MEETINGS

Mention should be made of group meetings of poets held in recent years in Hanover and Norwich. To these came, informally, men and women either amateur or professional for the reading and discussion of new poems. Sometimes undergraduate poets were invited to join their elders in the presentation and discussion of work. The casual and friendly air of these meetings was civilized, yet criticism could be keen.

Nor should one forget to mention the pervasive figure of Robert Frost, who appeared twice each year for years to delight the College and the community. After his large readings he enjoyed repairing to the house of President Dickey, or to Professor Cudworth Flint's, or to Edward Lathem's, or to that of some other professor, for all-male conversations with a small group of old friends. In these he invariably did most of the talking, to the new delight and instruction of his friends, and sometimes had to be restrained from carrying on into the small hours. These were rare occasions not to be forgotten by those who have heard, in a small circle, Frost's witty, expansive, wise and provocative comments on everything from Ezra Pound's London of 1912 to Khrushchev's Moscow of last year.

With Frost's death on January 29 at 88, Dartmouth has suffered the loss of a warm friend as well as that of a great poet. We will have to get used to not seeing his familiar figure here and must go back to his poems which will be read "ages and ages hence."

VOLUMES OF STUDENT POEMS

In June 1958 I selected Thirteen Dartmouth Poems from the undergraduate writing of the year, mostly from my own class in the writing of poetry. In a foreword I said, "Most often young poetry is sporadic, individualistic, and exists for the moment. It reflects current modes of feeling, contemporary preoccupations and predilections. So do these poems." I wondered if anything permanent would come from these young poets and reprinted "The First Autumn" by Marshall Schacht, from The Arts Anthology, DartmouthVerse 1925, which I deemed worthy of reprinting 33 years later, as I do now.

I acknowledged the active help of Ray Nash, who produced a handsome book, Alexander and Dilys Laing, and Professors Thomas Vance and Bink Noll.

The poets represented were Peter W. Eccles, Sinclair H. Hitchings, Tom Hyman, John R. Nash, Jacob Park, Robert T. Perron, David Rattray, F. C. Scribner III, Cary Packard Stiff, Robert Sussman, Howard R. Webber, Eugene Vance, and Art Wolff.

In 1959 Thirty Dartmouth Poems appeared at the end of the college year. In my foreword I was trying to define the mystery behind poetry and was looking, in undergraduate poetry, to see if young poets could penetrate beyond appearance. Of poetry I said, "It is spiritual and it is sensuous and in its sensuous meshes the spirit is caught as in a thicket; it tries to release the spirit out of the thicket of our flesh and blood, but is happily caught there."

This book showed less control of form than was shown in the first one. There were looser, longer poems, more experiments in verse. The poets were Richard Baldwin, DeWitt Beall, Howell Chickering, Robert Coltman, Lou Gerber, David Greenstein, George Hand, Karl Holtzschue, Alec Lampee, Joseph P. Nadeau, John R. Nash, Robert T. Perron, Lloyd Henry Relin, Fred Scribner, Cary Stiff, and Art Wolff.

Forty Dartmouth Poems appeared in June 1962. This book was published on the Charles Butcher Fund, as were the first two, but was copyrighted by the Trustees of Dartmouth College and was distributed by Dartmouth Publications. In an Introduction I was still concerned with the timeless quality in poetry, this time naming some poems, but also naming poems which were dominated by contemporary reality. "Perhaps the timeless notion is too hard."

The poets were DeWitt Bell, Richard Borofsky, Ross Burkhardt, James T. Corbet, Anthony Graham-White, Bruce Ennis, Richard Heraty, Allen Houser, Frederic Jarrett, Carleton Kent, Alexander Lattimore, Michael Marantz, Carl Maves, Robert Moseley, Daniel Muchinsky, David Petraglia, William Laßiche, Paul Roewade, Nevin Schreiner, and John Unger.

This book enjoyed a richness of poetic execution with variety of subject matter. The large number of poems was culled from several hundred which were considered, yet even this representation probably did not exhaust all the publishable poems written at Dartmouth in one year.

In conclusion, I should say that Dartmouth, as a member of the academy as defined above, has through the years provided an atmosphere where poetry in the twenties was possible; in the thirties, forties, and fifties probable; and, I should like to hope, in the sixties and later assured. But there is no guarantee anywhere along the line of years that poetry of permanent value will grow out of the cultural climate existing at Dartmouth or at any other institution. This is part of the excitement of poetry, its vast potential as distinguished from whatever is its actuality. To deal with the young is to think of imagination unlimited. Dartmouth is willing. We await the calls of the spirit. "Say not the struggle naught availeth."

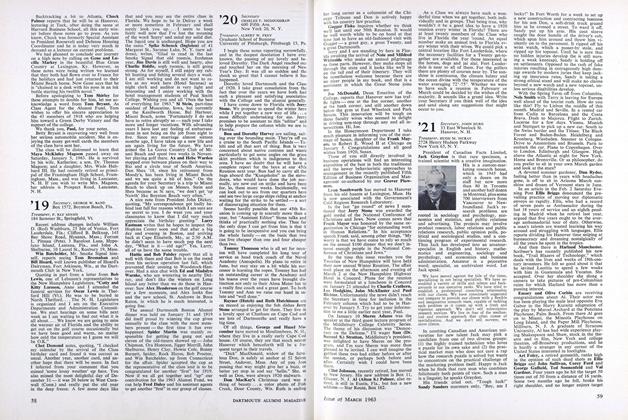

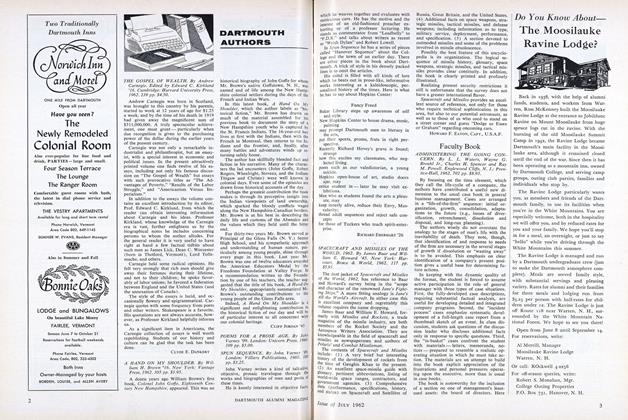

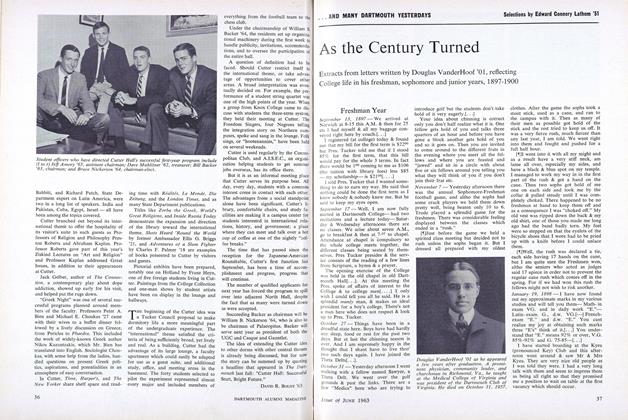

Richard Eberhart '26 (standing center), author of this article, served as Consultant inPoetry to the Library of Congress in 1959-61. He is shown in Washington in May1960 with (l to r) Oscar Williams, poet and anthologist; the late Robert Frost '96,whom he succeeded in the post; Carl Sandburg; L. Quincy Mumford, Librarian ofCongress; and Hi Sobiloff, poet and patron of the arts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

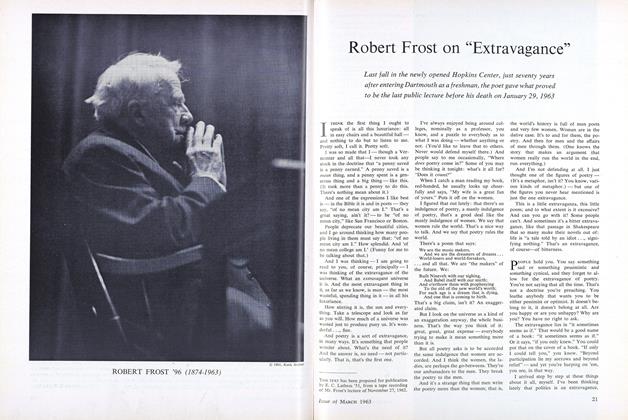

FeatureRobert Frost on "Extravagance"

March 1963 -

Feature

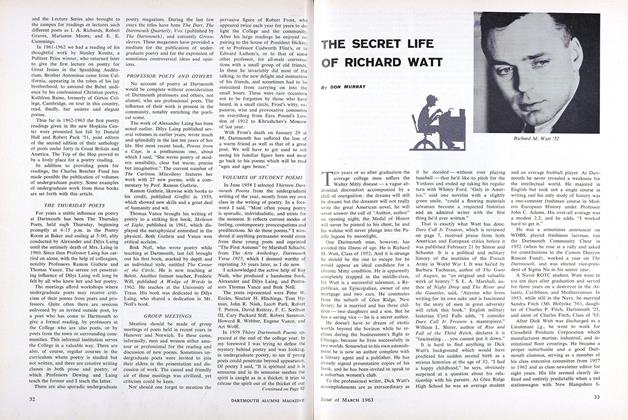

FeatureTHE SECRET LIFE OF RICHARD WATT

March 1963 By DON MURRAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1963 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY -

Article

ArticleScholarly Stimulator of Comparative Study

March 1963 By G.O'C. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1963 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

March 1963 By ROBERT W. MACMILLEN, DONALD G. RAINIE

RICHARD EBERHART '26

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

September 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1954 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR, Richard Eberhart '26 -

Feature

FeatureThe Poet as Teacher The Poet as Teacher

November 1956 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Books

BooksSPUN SEQUENCE.

July 1962 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Books

BooksDARTMOUTH LYRICS.

NOVEMBER 1962 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Books

BooksPOETRY: A CLOSER LOOK

FEBRUARY 1964 By RICHARD EBERHART '26

Features

-

Feature

FeatureOur Way in the World: A Conversation with John Dickey

January 1976 -

Cover Story

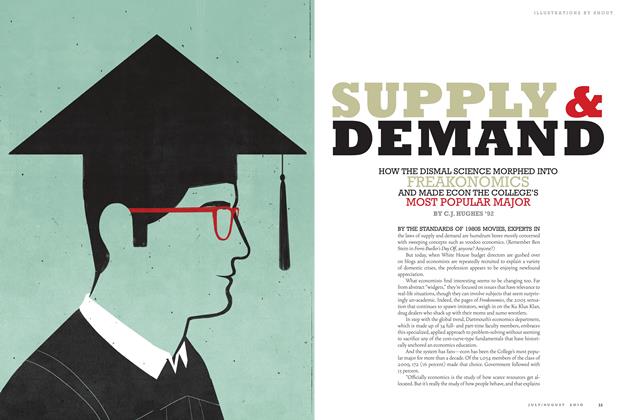

Cover StorySupply & Demand

July/Aug 2010 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureAs the Century Turned

JUNE 1963 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureUNITED EUROPE, THE GENERAL AND THE BOMB

MAY 1964 By HENRY W. EHRMANN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO MAKE A GOAL KICK

Sept/Oct 2001 By KRISTIN LUCKENBILL '01 -

Feature

FeatureThe Nautical Nyes

MAY 1972 By MARY ROSS