By being the first in the Ivy League to administer a daycare center,Dartmouth deals with a burgeoning national issue.

"All these years," said Susan Brown, director of the College's Child Care Resource Office. She laughed, "I feel I have nothing else to live for."

After 16 years of debate and small concessions to a big problem, the Dartmouth Trustees had just approved construction of a permanent home for the Dartmouth College Child Care Center the first institutionally run daycare program in the Ivy League. In January, ground was broken on College land on Reservoir Road for the new center, and by September, Dartmouth will be offering its employees 63 full-time child care slots for children from infancy to six.

Although the new facility meets only half the need indicated by local surveys, it is twice the capacity now availa ble, and the Trustees' decision has significance beyond the Upper Valley because few issues are as central to our time as the question of who will care for the children. According to the latest figures published in 1986 by the National Commission on Working Women, more than 62 percent of women with children under 18 now work outside the home. The Census Bureau predicts that the problem is only going to get more difficult: by 1990, the agency says, at least 55 percent of women with children one year old and younger will be in the labor force.

Because no federal agency currently surveys child-care matters on a regular basis, figures for numbers of children in care in this country date from 1982. In that year, there were 5.5 million children in daycare homes, 1.5 million in child-care centers, 10 million cared for at home by someone other than a parent, and 7 million "latchkey" children who are home without supervision. The National Commission on Working Women estimates that in the last five years, each of those figures except the last has risen by at least another million. The issue is no longer whether child care is a good idea, but whether the child care available is good care or poor care.

Of course, in many ways, that has always been the issue because daycare is not by any means a brand-new idea. Children have always been cared for by people other than their parents. The rich have hired wetnurses and nannies, and the poor have left their children wherever they could, somet imes untended, in order to earn their bread. In the days before the nuclear family, grandparents, aunts, uncles, sisters, and brothers were pressed into service in a way the modern world has forgotten.

But the extended family is long gone, and the mothers of the vast middle class by choice or necessity are now moving out of homes and into the workplace. Increasingly, American women are refusing to forego families in order to work outside the home wanting, like men, to have both jobs and children. The resulting child-care slack is not being picked up by fathers, and it has become axiomatic that the employment of women requires the availability of care.

Many middle-class parents find good child care prohibitively expensive, however. In 1984, working-day care for a three-year-old cost between $1,500 and $4,000 a year. For infants, good care is even more expensive Dartmouth's child care included. The monthly fee at the Dartmouth Center currently ranges from $220 to $440.

Even at the low end, a year's fees total 22 percent of the average Dartmouth secretary's $12,000 salary hence the dilemma of mothers like Suzanne Leßlanc. A computer trainer and systems coordinator at the College and a divorced mother of three, LeBlanc has her four-year-old daughter at the Dartmouth Center, but it is costing her a quarter of her income and she cannot afford that much longer. "I would love to leave her there through the summer," says Leblanc, "because I really like the center. But it's just too expensive."

She speaks with distress about the prospect of finding a good daycare home for her daughter. Homes are less expensive, she reports, but many she has seen are crowded, profit-oriented places in unattractive basements.

Good care is scarce everywhere, but in the Upper Valley, it turns out, there is a real dearth. Unemployment in the area is among the lowest in the nation, and, since pay scales associated with child care are no better here than elsewhere, employers such as McDonald's can attract more help than daycare centers.

Because of this problem, College support of child care was from the beginning a primary objective of the College's women faculty, staff, and administrators but it has been the last to be addressed. "Better representation on the faculty, coeducation, the Affirmative Action plan all these issues were resolved at a much quicker pace," observes Marysa Navarro, Professor of History and Associate Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

The push to fill the gap began in 1971, when Dartmouth's first Affirmative Action plan was drafted in recognition of a need to recruit more women faculty and administrators. That same year, the Dartmouth Women's Caucus recommended to President Kemeny that the Affirmative Action Review Board survey employees to determine child-care needs anto provide care if necessary; Despite such parallels as Dartmouth's tuitionassistance scholarships for faculty offspring, the administration refused this proposal on the grounds that it "would discriminate against single or childless persons in the form of a bonus for those with children."

The caucus continued to press for a response to the child-care needs of Dartmouth employees, and in 1972, the College unbent to the extent of granting a mortgage at commercial interest rates to the fledgling Norwich Daycare Center, which was interested in buying the building it was renting. The Caucus then sent to all Dartmouth employees and married students the first in a long series of child-care questionnaires, which drew an impressive 50-percent response. Even at that early date, 51 families testified that the lack of good child care had prevented a parent from working, and 208 families strongly supported the idea of a College daycare center.

Four years later, the first of Dartmouth's professional child care workers was hired on a quarter-time basis. The main duties of Vicki Winters, a former social worker who had been active in local child-care issues, consisted of compiling referral lists of child-care homes and centers. But she also started setting up meetings among the various centers in the Upper Valley and began to push the College to underwrite an infant program.

"We met and met and met and met and met/' she recalls and finally Dartmouth agreed that a private inf ant-toddler program could have the rent-free use of a small unoccupied house. The house was big enough for only eight children, but it was a start, and in 1979, eight years after the first call for attention to the daycare issue, the Upper Valley Day Nursery, Inc., opened in a Dartmouth building.

In 1981, after a decade of modest gains in Dartmouth's commitment to child care, David T. McLaughlin took office as president. From the start, he showed particular interest in the issue. "If this college is anything," he says, "it is people, and the quality of the people here will determine in the long run the quality of the institution and I don't mean just the faculty, either. Child care is as important for the staff as it is for the faculty and the administration, maybe even more so." McLaughlin advocates the positive approach pioneered by business which views the need to support child care "as an opportunity to enhance the attractiveness of the workplace."

The same year that McLaughlin took office, Susan Lloyd Brown replaced Winters as the College's child-care coordinator. The London-born Brown quickly helped set up after-school programs in nearby Lebanon and Thetford and convinced the College to seed "Haydays" a summer day camp for school-age children that compensated for the sudden closing of a day camp in Lyme, New Hampshire. She also oversaw the expansion of the Upper Valley Day Nursery to two houses and orchestrated an administrative merger between it and the Norwich Daycare Center.

Still, Brown and the Child Care Advisory Council a group composed of College employees decided that this wasn't nearly enough. The solution as the council saw it was a Dartmouth College Child Care Center. In 1984, after a couple of years of politicking, the council got the administration to agree to sponsor such a center. To be sure, it was only a three-year "pilot" program, in space rented from the local elementary school, for 30 children only. True, its continuance was subject to an outside evaluation to satisfy the doubts lingering in some administrative minds. But it would carry the Dartmouth name and had been granted a Tuition Assistance Budget that allowed the facility to offer a sliding fee scale.

At the same time, Brown was also working on the Child Care Project a cooperative effort among local businesses to respond to the Upper Valley's still-critical child-care problems. The project, currently supported by United Way and 23 employers, offers its members' employees daycare information and referrals and also has a state grant to supply equipment and training for people interested in starting daycare businesses in their homes. Dartmouth's contribution to the Child Care Project includes on-campus office space as well as a portion of Brown's time as director.

When the new Center was approved, Brown became executive director. To run it, she and the Council selected Jeff Robbins, who had been program director of the Greater Manchester Child Care Association, a private nonprofit New Hampshire concern with two centers serving more than a hundred children. The space in the elementary school was leased and was bought and small equipment was scrounged.

(One special contribution, a clawfoot bathtub, was painted yellow, filled with pillows, and given a prominent place in the threes' room.)

Then, at last, in September of 1984, President McLaughlin cut a red paperdoll ribbon at the grand gala opening of the original Dartmouth Child Care Center.

After one year of operation, the Center was completely full with a lengthy waiting list, 35 enrollees, and an "exemplary" rating by an outside evaluator.

But there were other problems. The elementary school needed its space back, and the pilot program did not begin to meet the needs of the College community. A questionnaire done in 1984 had demonstrated a minimum need for 120 child-care slots among employees.

The Center's evaluation committee recommended as an interim solution a center for 63 twice the size of the current center. The College was also urged to continue supporting the Child Care Project, since many Dartmouth employees' children, infants especially, will always be cared for in private daycare homes such as those the Project supports.

On December 16, 1986, the Trustees said yes as an interim step in the challenging process of meeting Dartmouth's child-care needs. "It's a sound step for now, but no complete answer," says McLaughlin. "There will probably be further expansion down road."

Susan muses about how odd it was in her childhood to have a chum whose mother worked and who was in daycare. "But now it's an aberration if a child is not in some program," she observes.

"The next generation is being raised not only by parents but by child-care providers too," continues Brown. "Our job is to ensure that those children are receiving good quality care and early childhood education and that their lives and the quality of their families' lives are decent. Because we want a decent future, and these children are the future."

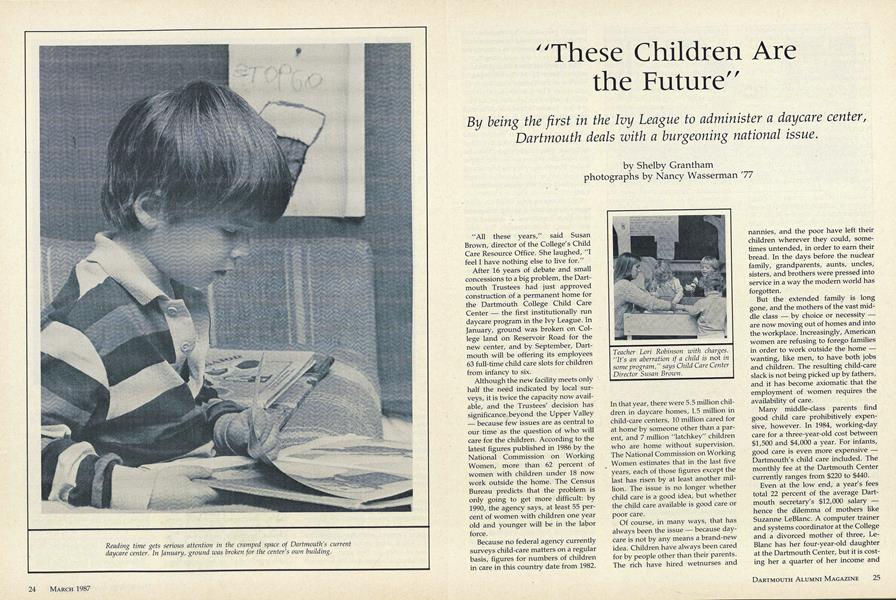

Reading time gets serious attention in the cramped space of Dartmouth's currentdaycare center. In January, ground was broken for the center's own building.

Teacher Lori Robinson with charges."It's an aberration if a child is not insome program," says Child Care CenterDirector Susan Brown.

Supervised "free-choice projects" at thecenter include Art, Sensory, Table,Dramatic, Housekeeping or plainblocks.

Shelby Grantham, former senior editor ofthis magazine, is Dartmouth's director ofPublications for Development.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

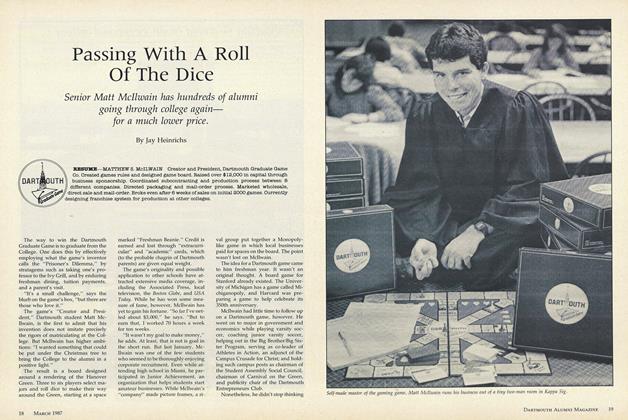

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

March 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureThe Magic Bullet

March 1987 By B.J. Schulz arid Mary McFadden -

Feature

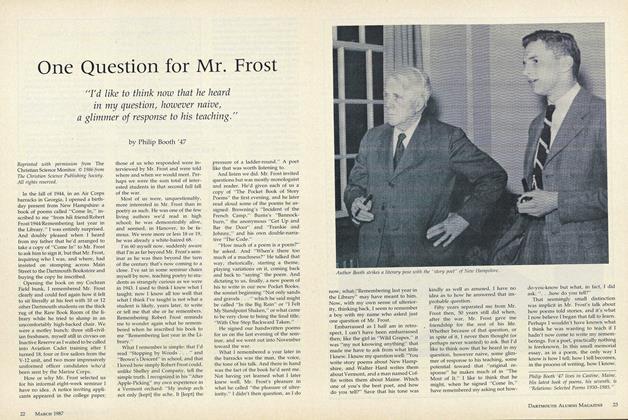

FeatureOne Question for Mr. Frost

March 1987 By Philip Booth '47 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

March 1987 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

March 1987 By Ken Johnson -

Article

ArticleSenior Epiphany

March 1987 By Lesley Barnes '87

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe conquest of Kiewit (sort of)

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature"All Deaned Out"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature"The Highest-Ranking Woman in American History"

MAY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

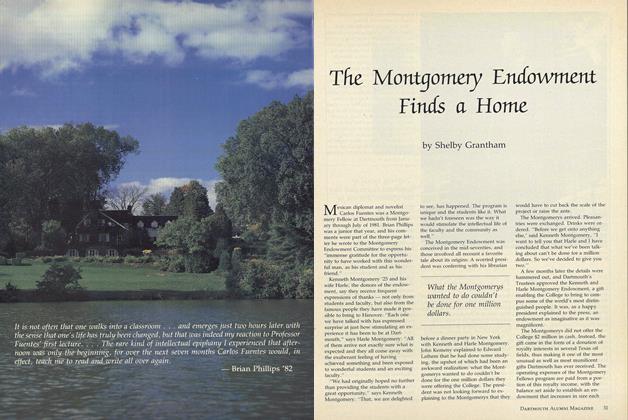

Cover StoryThe Montgomery Endowment Finds a Home

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSeeing Farther than the Green

September 1976 By BLISS K. THORNE and NANCY DECATO -

Feature

FeatureMaking Music

November 1978 By Dana Grossman -

Feature

FeatureNine-Man Council Charts Course for Development

January 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

DECEMBER 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Cover Story

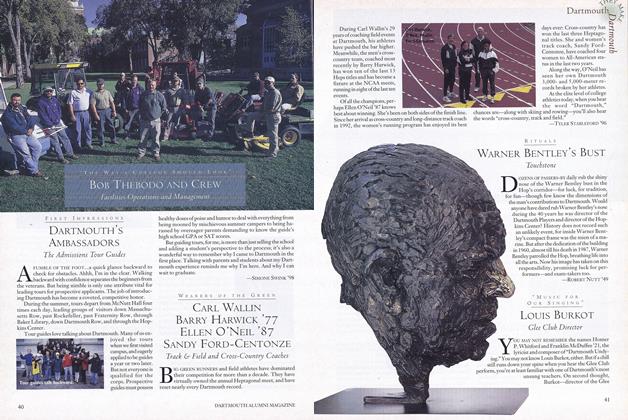

Cover StoryCarl Wallin Bary Harwick '77 Ellen O'Neil '87 Sandy Ford-Centonze

OCTOBER 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96