Except for a Florida postmark, whichis small kelp, the editor has no clue tothe identity of this article's alumnus author, who hides behind the nom de plumeHomer U. Feep. Maybe others among ourreaders have collided with the opinionheld by Mrs. Feep.

THE bad guys wear black hats and mustaches. But the good guys, under the white hats, are clean of upper lip.

The bad guys ride black horses, the good guys mount on white, and the clue to an adult Western is a rider forking a grey.

But you can't tell a Dartmouth man even with his freshman beanie.

My wife doesn't believe this. She used to tell me - well, hell, she still tells me - that you can always tell a Dartmouth man just by looking at him. There is, she claims, this "certain look," never defined, that immediately identifies him as a Dartmouth man.

For years, I worried about the "certain look." I didn't know if it was good or bad. During those perplexing years, I spent considerable time in front of the mirror. I was searching for the "certain look." What I saw was a face eroded by the steady drip of Martinis, the cheeks as finely-veined as a dollar bill and the eyes a blurry testimonial to Gordon's gin with damned little Vermouth. If this was the unmistakable look of a Dartmouth man, I wished to God I'd gone to Oberlin.

But I discovered - and don't ask me how - that the idiot bride liked this "certain look," much as she has a hankering for Busch Bavarian commercials without liking the beer. What she does, she reads into it. For instance, she keeps seeing me on skis. She knows good and damned well that I can't ski, never could ski and, in fact, shudder at the very thought of skiing. This means nothing to her. She sees the "certain look," puts me on a pair of skis and that's that. This may seem like a small matter to most people - but most people never went Dartmouth. They don't know what it's like to be accused of driving the steel points of their ski poles into the broadloom while sitting in an easy chair with that "certain look."

She also sees me climbing a mountain from time to time. I tell her that I never climbed a mountain in my life. She smiles placidly and goes back to seeing me plant a Dartmouth banner on the summit. I did not get up there easily, you understand. No one had ever been up there before. I had to hack out the route and overcome dangers that would have defeated the ordinary man - the man from somewhere other than Dartmouth, that is. The project seemed doomed from the start, but never you mind, I had that "certain look," and nothing on earth could stop me. I think I must pant a little when I reach the top, and perhaps I sink to rest on one knee, but other than that no one would guess what I have just been through.

No one but the wife of a Dartmouth man. She knows. She has seen this "certain look."

I think I am blond and have a crew cut. I believe I must be at least six-feet-two, weigh 190, have lean hips and wear a white hat. I know I have extraordinary stamina and the strength of Samson, otherwise I would not be able to race up mountains as easily as I do. I know, as all Dartmouth men must modestly know, that I am uncommonly brave and that the "certain look" has helped me out of more than one ticklish spot. With all that — as if such qualities were not more than any one mortal deserved - I am frightfully brilliant. I mean it. Frightfully. The knowledge that lies behind the easy-going, loving "certain look" would terrify the man who looks as if he had been graduated from some lesser place. And yet I am modest and unassuming, tolerant of others and kind to waiters.

If I hadn't gone to Dartmouth, where I got this "certain look," I would be unbearable.

Occasionally, the unassuming modesty that is a Dartmouth man's by right of marriage forces me to demur. I am not really all this, I attempt to say. Surely, in a world as large as this one, and with all the people there are on it, there must be someone as noble as I - someone other than a Dartmouth man, that is.

To which she smiles, brushes off the interruption and takes me back to the ski slope, or the mountain peak, or she pits me in deadly combat against the IBM machine, and if I do not immediately come up with an answer to the youngster's arithmetic problem, it is only because daddy has his mind on deeper things, as any fool can plainly see from his "certain look."

There are those moments when I feel a grave concern, and not only because of the responsibilities that rest upon me. I can handle world affairs in a breeze with my "certain look" and there is nothing on the local scene that can stand up against my cool logic and keen analysis. But what worries me are all those thousands of other Dartmouth men who are walking around with their "certain look" and the undeniable assets that go with it. If all of us have it, how is any woman to choose between us?

I do my best to keep her from meeting other Dartmouth men because I am too far gone around the track to have my home wrecked and am too damned weary to start the race all over again. But some-day, by pure coincidence, she will see that "certain look" across a crowded room and there, by God, will come her moment of decision. No wonder so many of us don't attend reunions.

Sometimes I wish I really had gone to Oberlin. Sometimes I even wish I hadn't gone to college at all. I don't know how much longer I can live with this thing. I submit, sirs, that the "certain look" of a Dartmouth man is not to be taken lightly, though I have only my wife's word for it that the phenomenon exists.

A few years ago, fate threw Tony Galento and me together and the rapturous moment was caught for eternity on film. I just took a look at the picture. Tony's in pretty good shape and it seems to me he has a "certain look." I pointed it out to my wife, thinking to quash this damned thing forever, but she couldn't see it at all.

She says it isn't the same. Maybe other Dartmouth wives know what she's talking about but I sure don't.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

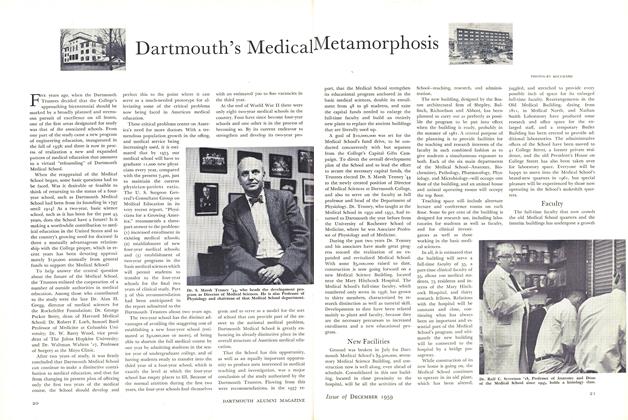

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Metamorphosis

December 1959 -

Feature

FeatureStudents from Abroad

December 1959 By J.B.F. -

Feature

FeatureMary Baker Eddy and Dartmouth

December 1959 By JOHN B. STARR '61 -

Feature

FeatureSTEFANSSON

December 1959 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

December 1959 By JOHN HURD, LINCOLN H. WELD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER