CHIEF JUSTICE Charles Cogswell Doe, New Hampshire's renowned nineteenth century jurist, is the only Dartmouth graduate included on Roscoe Pound's list of America's ten greatest judges. He attended Dartmouth from 1846 to 1849 after preparing at Berwick Academy, Exeter, and Andover, and taking his freshman year at Harvard College.

The fact that there is no record of how he traveled from his home in Somersworth (now Rollinsford) to Hanover makes him an exception to what was almost a Dartmouth rule. It seems to have been a favorite pastime in those days for graduates to create personal legends of the hardships they suffered peregrinating the New Hampshire woods on their way to college. It might be expected that this tradition began with Daniel Webster's famous arrival on horseback, but actually it started earlier, when one group of boys in the Class of 1778 put their luggage on a single horse and walked beside it all the way from Connecticut. Judge Wells who was graduated in 1814 didn't even own a horse. He carried his books and wardrobe on his back. So did another judge, Jonas Cutting, although he was lucky enough to have his father take him half way on the family horse. The elder Cutting couldn't afford to leave his Croydon farm for very long, so Jonas traveled the rest of the way on foot. Such impecuniosity continued right up until Doe's own time. It took his future rival at the bar, Amos Tuck, two days to journey to Hanover from Parsonfield, Maine, in 1832. And since Dartmouth has always been able to produce blustering sons, these achievements would certainly have been surpassed by later generations if more modern forms of transportation hadn't come along.

As it turned out, it remained for Charles Lord, Doe's Greek teacher at Berwick Academy, to give the tradition its crowning touch by doing it all in reverse. Lord's friends were disappointed when he was graduated without honors. They considered him a failure and his father even treated him with ironical disdain. To show everyone he was truly the Dartmouth type, he decided to save the five dollars coach fare and walk home. Just as he expected, his haggard condition when he arrived in South Berwick, after traveling thirty miles a day on foot without sufficient food, aroused such compassion that he completely disarmed his parents of their reproaches.

In many ways the Dartmouth Charles Doe first saw was reminiscent of New Hampshire's former days. It was certainly the last stronghold of Congregationalism. The old faith ruled the College as it had once ruled the State. So powerful was its influence that just before Doe arrived a professor who had committed the impropriety of conducting Episcopal services at his home was forced to resign, while during Doe's senior year another instructor was fired for publishing two pamphlets distasteful to the watchdog of the Congregational Church, the American Tract Society. Yet Dartmouth was not affiliated legally with any religion and even had a clause in its charter that forbade theological tests.

This domination by the Congregationalists stemmed from the Dartmouth College Case. Charles Doe's father, one of the leaders of the Federalists Party in the General Court, had been an active supporter of the College in its struggle against the University, and, although not a Congregationalism seems to have approved the fact that the clergy, since they raised most of the funds, had obtained a financial stranglehold upon the institution. The faculty, made up chiefly of ordained ministers, seemed perfectly content with this state of affairs. In fact, Charles Haddock who taught intellectual philosophy regarded it as quite desirable. "Let not an inch be yielded so long as it can be maintained," he pleaded. "The interests of liberty, of truth, of the soul are concerned in this issue." During the years Charles Doe attended Dartmouth Haddock had little need to worry. The clergy of New Hampshire had planted Nathan Lord securely in the President's chair and he was, indeed, one of their own.

The scion of South Berwick's leading family, Nathan Lord was undoubtedly the reason Charles Doe was sent to Dartmouth. Doe had been removed from Harvard partly because its new President, Edward Everett, had seemingly lost control of student discipline and was completely baffled by the boys. Fresh from his post as Ambassador to the Court of St. James's, he was fair game for the undergraduates he would not stoop to understand. They mocked his British airs by wearing blue-tail coats to chapel. Not knowing how to cope with them, Everett had to content himself with complaining at faculty meetings. He told the boys that young gentlemen did not blow their noses; in England they used handkerchiefs. The next day at chapel everyone waved handkerchiefs at him. It was good fun but it worried Doe's parents. On top of this, Harvard was under heavy attack from conservative quarters. During the administration of Everett's predecessor, Josiah Quincy, the college had turned its back on the oxthodox religion of New England and had paid a heavy price, losing the favor of much of the population. The great American political shell game which McCarthy practiced so well, of playing on the public's suspicion of new ideas by baiting Harvard, had already begun. Staid, sound Dartmouth seemed a safer place for young Doe. On top of this, Nathan Lord was an old friend of the Does. The two families had been associated in shipping and were neighbors, living on opposite banks of the Piscataqua River. In fact, Charles Doe's first love was Nathan Lord's niece, Connie Hayes, of South Berwick.

Although a graduate of comparatively liberal Bowdoin, Nathan Lord's mind was really moulded at the Andover Theological Seminary, which, when he attended it, could best be described as a den of uncompromising orthodoxy. He had emerged from Andover at a time when the walls of traditional Puritanism were crumbling before the onslaughts of democracy personified by New Hampshire's Toleration Act. Yet this did not daunt his hyperorthodoxy one bit. Armed with an intellect as brilliant as it was narrow, he became one of God's chosen warriors ready to do battle against established religion's greatest foe - secular thought. He was more conservative than even the most rigid of the oldschool precisians. To him any deviation from the teachings of the early New England fathers was heresy. Striding back and forth across the "Sand Ridge," a long dune northwest of Hanover, Lord formulated his theology which condemned everything that made "happiness the end of living." He liked to feel he was jostling with ideas much as Jacob had struggled with the angel at Peniel.

Once Lord adopted a tenet he lost no time publicly expounding it, and by the time Charles Doe arrived at Dartmouth in 1846 many of Lord's notions were famous and often controversial. He had absolutely no sympathy with "the sentiment and romance which had infected the descendents of the Puritans," and vigorously attacked any new ideas which conflicted with revelation. His entire philosophy of life was grounded upon his belief in the literal accuracy and inerrancy of the Bible. "All we can know in theology," he used to say, "is contained in the Bible." And this must have made him a well-versed man in his own estimation, because he knew it almost by heart. Someone once stole the copy from his desk in the bare, cold College chapel and without batting an eye he repeated with perfect aplomb the entire 119 th Psalm. Everybody agreed that Nathan Lord was a good prayer, despite the fact that he occasionally lost his voice, once for a whole year. Some of the boys even enjoyed hearing him pray and he impressed people with the grasp of his thought, the strength of his faith, and the compelling power of his urgency.

In meeting Nathan Lord, Charles Doe encountered at first hand the old Puritan type which had been so common in New England as church deacons and social arbiters during the days of his ancestors. Lord's severity, his accuracy, his disdain for frivolity and hatred of evil, his confidence in the revealed word of God, and above all, his absolute trust in his own infallibility were qualities of the old Puritan code which was swiftly disintegrating before the irresistible effervescences and the secular attitudes which were to characterize Charles Doe's own generation. Unfortunately Doe was not interested in ethnography and Lord failed to stimulate him.

Although he would always be fascinated with the problems of education, heartily supporting the theories of Eliot, it is certainly true that at Dartmouth he was never inspired to exert much academic initiative, a very surprising fact when we consider his later capacity for hard work. It became almost a fetish with him to brag of how little he did in college. When Doe was at Hanover there was a tradition current that Daniel Webster, as a student, had never opened a book. Asked about this, Webster denied it indignantly. "I studied and read more than all the rest of my class, if they had been one man," he said. Adding typically, "And I was as much above them all as I am now." No such denial was ever uttered by Doe. In fact, he always sought to create the impression that he was an idler in college. He told Jeremiah Smith, his associate on the New Hampshire Supreme Court and later Professor of Law in Harvard, that he not only failed to study the prescribed textbooks but didn't even own some of them. Congressman Joshua Hall, who was two classes below him, felt that what Doe really intended to imply was that he had had an easy time of it at Hanover compared with his after-work in law. Actually he probably meant just what he said. He did little work at Dartmouth because Lord's style of tutelage, saturated with theopneusty, did not infect him with a desire to study. "Stanley and I competed for the foot of the class," he said some years later referring to an associate justice, "and I beat Stanley." Yet he must have done well academically for he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. This proves that he did not neglect his studies entirely, and Judge John Allen, in his 1921 article in the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE, was probably right when he reasoned that Doe was referring to his remarkable ability to absorb knowledge when he called his college days the easiest of his life.

Despite the fact that it offered little in the way of academic stimulation, Dartmouth was an important influence on the development of Charles Doe, for it was here that he first gave indications of his greatest social attribute - his ability to get along well with men. At Berwick Academy, Exeter, Andover, and Harvard he had made no lasting friendships; in fact, he did not even mix well. At Dartmouth, on the other hand, he struck up several intimacies which lasted his entire life. Perhaps the closest were with Isaac Smith and Clinton Stanley, who would be associated with him on the Supreme Court. One jocund classmate has attempted topin-point the very time that Doe ceased being an unpretentious, rather shy farm boy and first began to show signs of his future egregiousness. In the autumn of 1848 the Northern Railroad was opened from Franklin to Lebanon Center, and since Daniel Webster was to be the orator of the day, some of the students decided to go down. When they reached the depot they found the yard already crowded, for more than four thousand spectators were on hand. Doe and some of his friends made their way to the platform and sat on the edge with their legs dangling into space. No sooner were they seated than Webster wearing a pair of cowhide boots walked up behind them. It was whispered around that this was a good chance to come into contact with the great man, so several of them, including Doe, turned and put their hands on his boots. A class historian says that prior to this neither Doe nor Clinton Stanley had shown any marked ability. After that both seemed to flower out with unsuspected power. "This was a turning point in their history," he wrote. "The class have always attributed the change to that contact with Webster's boots. Several other members of the class touched the same boots, but the infection did not take."

There is little doubt that Charles Doe thoroughly enjoyed his three years at Dartmouth. He remained loyal to the college throughout his life, despite the fact he sent his sons to Eliot's Harvard. In 1859 he returned for his tenth reunion and in 1873 he accepted an honorary LL.D. degree. Yet the orthodoxy of Nathan Lord had left a bitter taste in his mouth, as evidenced by a letter he wrote in 1886 to Fletcher Ladd, the son of a former associate justice, William S. Ladd. The boy, while at Dartmouth, was considered promising, although quite lazy. Once, in a splendid bit of Oneupmanship, he remarked that "class leadership pleases other people much more than it does me, so I will let them enjoy that kind of fruit." As a result of some incident the faculty voted to graduate him and a student named Lovell without a degree. When Doe heard the news, all the storedup resentment which his inquisitive nature had experienced during the three frustrating years under Lord came to the surface, and he wrote Ladd one of the strangest letters of advice any disgraced youth has ever received. In his biography of William E. Chandler, the late Professor Leon Burr Richardson, undoubtedly exasperated by the poor spelling and grammar he sometimes encountered from his Dartmouth students, delightfully remarked that Doe's letters were "written in the fine feminine hand of the jurist, page after page without correction or erasure. . . ." This letter was no exception:

"As the Dartmouth is the only N. H. paper that has come to my house for a long time, & as I had some knowledge of its managing editor, I have read it regularly & have been led by my acquaintance with him, & his family & Lovell's father, to take an interest in the affair which has ended in the graduation of yourself & Lovell without a degree, but summa cum laude, as they say at Cambridge.

"Pardon a suggestion from an old man who admires your equanimity & pluck. If the trustees do not overrule the faculty (as it is to be presumed they will not) you will have an opportunity to render the world an important service by demonstrating, in a striking manner, the worthlessness of college degrees. The common ignorant estimation of them is a cause of much evil, & a superstition that ought to be exploded. I am sure that a majority of graduates would have been better off if that majority had not gone to college.

"You start now with the greatest applause from all candid minds who are informed of the circumstances of the completion of your college course, but under a cloud in the belief of others, not candid, or not informed.

"I cannot resist the impulse to urge you (& by 'you' I mean both of you) to hold fast forever to that imperturbable coolness, self-control & courage with which you met this petty persecution. Scarcely anything is more fatal to success than the habit of emotional agitation. Never mention or refer to your expulsions. Carry yourselves as if there were no Dartmouth College. Civility may require you to answer questions on the subject; but I should answer them most briefly. Show by your demeanor that it is the future & not the past you are thinking of. Express no regret, no resentment. Display no memory of the tyrants from whose dominion you are happily delivered. In contrast with their childish spite, exhibit the silent good-natured magnanimity of men too elevated & too large to stoop to wrangle with anyone, or to embitter your own lives by bearing grudges against those who used you ill. You know theoretically that it is the way to heap coals of fire on an enemy's head. Are you capable of holding out to the end on that high plane?

"There is no more power in the faculty of Dartmouth College to harm you than there is in the same number of yellow dogs, yelping in the streets of Constantinople.

"The only way in which your missions can receive damage from the D.D.'s, LL.D.'s, Th.D.'s, A.M.'s & the rest of the Hanoverian alphabet, is by your recognizing the existence of the personal quarrel they have attempted to fasten upon you. You will be sorely tempted, through a sense of righteous indignation, to remember & take notice of them & their detestable conduct. If you are equal to the emergency, you will not waste a moment upon them except in philosophically considering their illustrations of the creating power of circumstances.

"If farmers, merchants, lawyers & express men had been put in the place of the faculty, last Jan'y, they would not have disgraced themselves, the college & the state by the despicable squabble.

"The faculty are disqualified for their duties, by being nothing more than men of books. But if they were not men of books they would be disqualified.

"Persons qualified by book-knowledge, temper & practical skill, for teaching & managing the students of a non-catholic college in this free country, are exceedingly scarce. Where one hundred are needed not more than one can be found.

"To be vexed with the unfitness of the Dartmouth Faculty is to be displeased with the order of nature. If your lives should fall under the influences that have made them what they are, you would probably be as unfit as they are for their work.

"The position of a mere priest or teacher of books is narrow & belittling. It is extremely difficult for the largest & most liberal & just man, remaining long in that position, to become a competent leader of students. One of the most injurious influences of the place comes from the exercise of great power, developing excessive conceit, egotism, sensitiveness, an exaggerated & ridiculous idea of one's comparative value & consequence in the world, an inability to understand & practice the doctrine of equal rights, & all the qualities that make despotism vexatious & odious.

"For a quarter of a century, I have had occasion to observe & feel the enormous danger to which you expose a man's character, by entrusting him with power over the persons & the rights of other men. There is nothing in the business or surroundings of a college professor to guard him against the danger. These Hanover gentlemen, like other spoiled children, are the mere products of their environment. They are so ignorant as to suppose the graduate's degree is of some value. By work that will show them their mistake, you can do much to correct a very prevalent and very mischievous error. For public usefulness in that direction, they have given you a peculiar opportunity, of which, I judge from your reputations, you will be likely to avail yourselves.

Ys truly

C. DOE"

Charles Cogswell Doe, Class of 1849, began his noted career on the New Hamphire Supreme Court just 100 years ago. He served as Chief Justice for 20 years, 1876 to 1896.

Symbolizing the 1959 Winter Carnival theme of "The Good Old Days" was this center-of-campus snow statue showing an old man wearing knickers, galoshes and a scarf.

JOHN p. REID, the author of this article, resides in Dover, New Hampshire, where he is assembling material about Judge Doe and will welcome communications from readers who can contribute such material.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

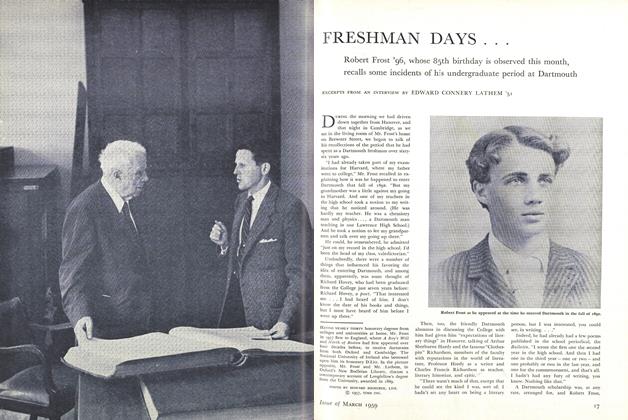

FeatureFRESHMAN DAYS...

March 1959 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureSCHOOLMARMS, GRAMMARIANS and ANARCHISTS

March 1959 By ROBERT S. BURGER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1959 By SCOTT C. OLIN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1959 By ROBERT L. MAY, EDWARD J. HANLON, BRUCE W. EAKEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1959 By CHESTER T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES, TRUMAN T. METZEL

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Cover Story

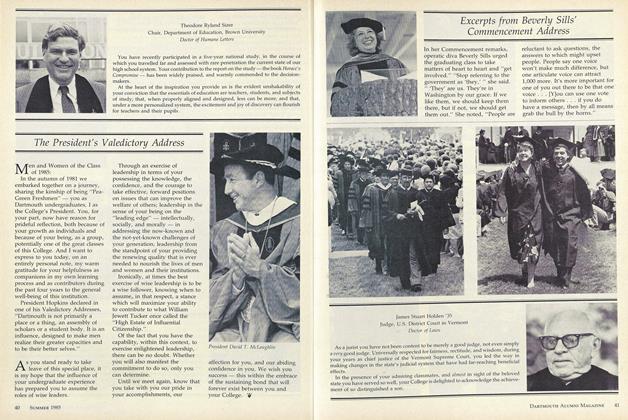

Cover StoryThe President's Valedictory Address

June • 1985 -

Feature

FeaturemAgnA CARTA: Seventh Crisis of John Plantagenet

November 1973 By CHARLES T. WOOD -

Feature

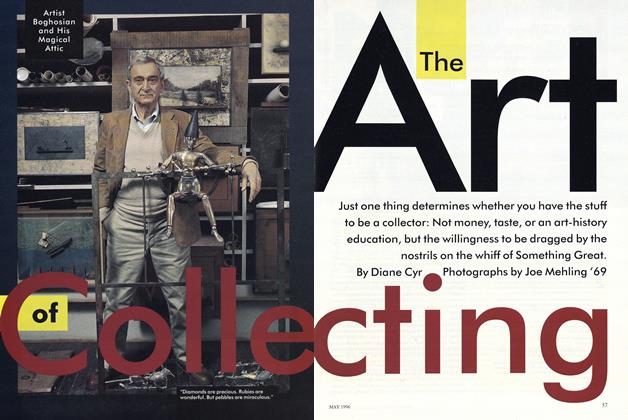

FeatureThe Art of Collecting

MAY 1996 By Diane Cyr -

Feature

FeatureMinimum Standards

APRIL • 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Feature

FeatureONE HUNDRED MASTER DRAWINGS

October 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40