Letter to the Editor

ALL voters can easily agree that national . survival is obtainable only through strength, and that to act otherwise, in hope for some internal or external force causing the Soviet Union to end its drive for world hegemony, is casually to toss their fate upon a roulette wheel. Within this area of basic agreement, however, there will be sharp controversy on the requisite elements of strength. One of these, the military ingredient, will be examined in the course of the Presidential election campaign.

It seems clear that this year's military policy controversy both underscores and reflects a critical issue now facing the United States: How does this representative democracy so operate its government as to mobilize its total resources in a long-term global struggle?

Over time, missiles will fade as an issue and be replaced with other momentarily acute decisions of technology or economics. The basic question, however, of the mechanism by which a democratic government develops and applies foreign policies, will remain. If there is to be a judgment on this question now, it appears that in the face of the nature of the Soviet challenge, a traditional strength of United States democracy may have become a liability — the mediocrity of its government.

Formal separation of power into legislative and executive branches, coupled with a profound concern with the protection of the "public interest," has assured government activity which has rarely been spectacularly effective and has seldom committed gross errors. Today, there may be serious dangers in relying upon middle-of-the-road foreign policies implemented by moderate programs executed at medium speed. Policies and programs of this nature are made all the more likely by the absence of a galvanic external threat which would overcome the existing inertia of mediocrity. The Soviet agricultural expert in Ceylon does not present an image of acute challenge to the United States, and it is this essentially non-traditional aspect of Soviet Union foreign policy which makes the activation of a dynamic foreign policy all the more difficult.

A prime factor inhibiting the development of a quick-footed and sustained foreign policy is the present Laocoon of shared responsibility between executive and legislative branches. When total domestic resources must be drawn upon, when military strength is a key element of foreign policy, when funds are all-essential, the Congress is co-partner with the President in the making of foreign policy.

The unsuitability of this shared responsibility stems from the fact that Congress operates principally on the bastruction contracts, ethnic groups' attitudes, and optical industries are examples of the many forces which are likely to have heavy influence upon foreign policy.

Pressure groups, however, are more an effect than a cause. A member of Congress does not seek election to implement platforms of foreign policy. The voter views the world from the center of concentric circles of diminishing importance in which the central zones of family, employment, and community count the heaviest. The function of Congressmen is to speak for citizens holding this perspective; the interests to which Congressmen are umbilically tied are domestic.

This fatal foreign policy flaw of the Congress is not easily eliminated, for the solution lies not in asking men to be what they are not, but in recognizing what they are, and devising a role for them which is consistent with their nature. Implementation of this principle calls for a restructuring of Congressional involvement in foreign policy. Two steps which can be taken immediately are:

1. To convert the foreign policy budget of the country (i.e. defense and foreign aid budgets) to a two-year appropriation.

2. To equip the President with an item veto over foreign policy legislation.

Both of these measures would diminish the impact of Congress upon foreign policy. While desirable, such steps would not change the basic Congressional role, and probably would result in the same degree of Congressional influence being carried out by other means. Rather, the problem must be met squarely.

The most direct method of reducing Congressional influence upon the making of foreign policy is to require only a onethird vote of Congress, rather than a majority vote, for legislative passage of a Presidentially introduced foreign policy measure. In effect, a two-thirds vote of the Congress would be required to override the President, just as is presently required to overcall a Presidential veto. Such a step will give a President a considerably free hand in forming the base of legislation for his foreign policy.

A provision of this nature would cause howls of rage from Capitol Hill that "the American voter is being deprived of his voice in the critical affairs of the nation." A little examination of this point demonstrates its untruth.

First, under the Constitution the President of the United States expressly is charged with responsibility for foreign policy, and, similarly, is directly responsible to the national electorate for his execution of this responsibility. Members of Congress have no such mandate, and more importantly, they have no such accountability. It is in the present circumstances of wide and deep Congressional involvement that the voter, who neither has directed nor can recall his representatives for actions affecting foreign policy, has the lesser voice.

Second, the voter increasingly has come to view the President as guardian of United States foreign interests. Recent Presidential elections have been concerned in large measure with ending a war and with preserving a peace. The voter's will, to the extent to which he has delegated it to the President, has a better chance of being applied if his designated foreign policy representative has the power to go with his responsibility.

Restricting the role of Congress appears consistent with both the letter and the spirit of today's Constitution. The voter continues in his right to control the President; he continues in his right to elect other officials responsible and responsive to his domestic interests, who, if necessary, can protect these interests against inordinate sacrifice to foreign policy.

Such an arrangement does not mean the demise of Capitol Hill in foreign affairs; the Congress can play a significant role in foreign policy by an expansion of its already valuable advisory role. It is ironical that the legislative may now be the best endowed branch of government to deal with broad policy questions. The executive agencies are so burdened with the details of program administration, reporting requirements, and budget defense that broad policy planning is becoming increasingly difficult. Unfettered with a requirement to act in response to domestic interests, the Congress may play a vital part by rendering general advice, as well as serving as safeguarder of domestic interests.

More than preserving representative democracy and permitting a more effective foreign policy, it appears that augmenting Presidential power at the expense of that of the Congress will have a positive effect of tending to make a better balloting process. The defense strength debate provides an example. While the Democratic Presidential nominee will criticize a perceived insufficiency of United States military strength, the Republican candidate has the option of implying that some of the responsibility rests with a Democratic Congress which has been partner to the present Administration. Next month's voter may be unable satisfactorily to allocate responsibility between the two parties.

The removal of the present ambivalence between Congressional and Presidential roles would solve this problem, and others like it which will arise in the future. With a placing of specific accountability upon the President, rather than following the present practice of viewing the President as generally responsible, it is more likely that Presidential candidates will run on or against a definite foreign affairs record. This permits a national discussion of issues, rather than a nation-wide exchange of slogans, to the voter's benefit, in his ability to act from a base of greater information, and in his increased ability, therefore, to guide the course of his country.

Bethesda, Md.

Mr. Wright, who received his master'sdegree in 1956 from the Woodrow WilsonSchool of International and Public Affairsat Princeton University, is working forthe Atomic Energy Commission, in thedivision of international distribution ofatomic energy for domestic use.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

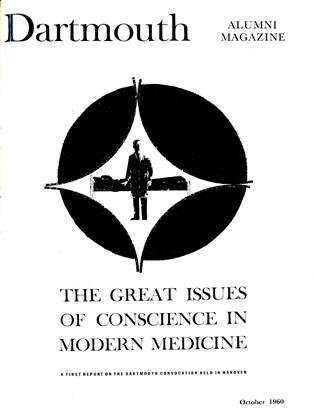

FeatureMedicine's Moral Issues

October 1960 -

Feature

FeatureA Rare Kind of Movie Star

October 1960 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Opportunity

October 1960 By WARD DARLEY -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1960 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

October 1960 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, ERNEST H. GRISWOLD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

October 1960 By WESLEY H. BEATTIE, GEORGE N. FARRAND