Dartmouth men tortured themselves for yearsover the Yale game - for no good reason

FOREWORD

In writing this account, I do not for a moment intend to belittle the awesome mental hazard to our football teams which the illusion of the Yale game jinx created, or the greatness of their achievement in overcoming it. In a situation where every injury to a key player and every unfavorable bounce of the football took on a sinister aspect and was magnified beyond all proportion, the determination, skill and will power of our boys, and the coaches and trainers as well, had to be outstanding to win victory. That they did so and rose above all obstacles in the doing is to their everlasting credit.

What I do wish to bring out is that this handicap which endured for so long had no substantial basis in fact, but was in the main created by a lack of common sense combined with a defeatist obsession in the Dartmouth family. Fortunately, within the same family - and above all, within the boys themselves - dwelt the wisdom and will to overcome it.

THERE is no Yale game jinx, and there never was one except in the fantasy of a gullible public, including many Dartmouth men. So far as freaks of fortune seem to have played a vital part in football games between Yale and Dartmouth, they have on the whole favored us. In other words, if you insist on conjuring up a jinx, don't forget he wears green. I realize that in making this intrepid statement I am running counter to the beliefs, or at least the expressed beliefs, of some members of the press, the public and, last but not least, the Dartmouth family. Also I am aware that a factual expose of the Yale jinx myth will not be accepted by those whose minds are already made up.

"Anyone who studies the matter of rationalization with care will come in due time to realize that attempts to change the beliefs of others, sane or insane, on any really serious subject (pure mathematics alone excepted) are merely a waste of time." So says Dr. Henry Yellowlees, famous British psychiatrist. While there may be exceptions to this rule, all lawyers will agree it applies to judges, and as to others, I'm darned if I don't think it is about right.

The jinx was born shortly before October 18, 1924, when Dartmouth was about to play Yale for the first time since October 13, 1900. On that earlier occasion, we made a very creditable showing against Gordon Brown's mighty eleven, losing only 17-0. This was a much better performance than either Harvard or Princeton put on that year against the Blue. Also, we must have played over our heads, since in that year we won only two games against four lost and two tied.

However, some newspaper statistician with a keen scent for what might take, before the 1924 game blazoned a headline: "Dartmouth Has Never Beaten Yale." It would have been just as meaningful if he had written that we had never beaten the Punjab Fusileers or the Beaver Meadow Marauders, because up to 1900 when we last had played the Elis, we had never beaten a single Ivy League team, or any team of real consequence in the football world. Nevertheless, the gullible public, including many Dartmouth people who should have known better, avidly swallowed the idea and began to cultivate it with an energy, persistence and ingenuity worthy of a far better cause.

The 1924 game was a humdinger, ending in a 14-14 tie between two top elevens, both of which finished the season undefeated. We played much of the game without the services of Swede Oberlander, who was konked on the head during the struggle and thereafter took little interest in the proceedings. Red Hall, however, proved a worthy understudy and ran the Elis dizzy with reverses. If it may be said that we had tough luck toward the end of the game when we took three or four unsuccessful belts at the middle of the Yale forward wall with the ball nearly on the goal line, the Blue cohorts can argue that pur choice of plays was poor, that during the game we had four fumbles while they had none, and that they in turn missed a field goal which would have given them a 17-14 win in the closing seconds.

We did not play Yale in 1925 when we had our first national championship team and, incidentally, the only Ivy League team that has won a national championship since World War I. Here, fortune may well have favored us. While I believe we were normally three or four touchdowns better than Yale that year, on the day we probably would have played them we were in a slump and barely squeaked by Brown 14-0. Nate Parker, our great captain, was out most of the contest with a bad foot, and nothing went right. Had we been playing Yale, we might have suffered the only blot on an otherwise magnificent season and have lost the national championship besides. So it looks to me as though the jinx was wearing a green jersey that year.

Came 1926, and Dartmouth had been riding a 22-game winning streak under Jess Hawley, brilliant coach and strategist, and a tremendous collection of players. But by 1926 most of the greats were gone, and we actually didn't have much of a team, for we lost every major game that year and ended up with a 4-4 record. However, before the game the fact that we had never beaten Yale was tub-thumped from coast to coast and everyone, especially the Dartmouth people, were in a high state of anxiety. At half-time we led the Elis 7-0, and things looked fairly good. Between the halves I went out of the stands for something or other and ran into a number of acquaintances and friends. Among them was a lawyer nursing the inevitable bottle of gin. After the usual amenities, I observed that things looked pretty good. His face instantly became as grave as though his star witness had flubbed his lines in a million-dollar case. He shook his head - seemed to shrink - and began a great song and dance recital about how we had never beaten Yale - the long string of defeats we'd suffered at their hands, and so on. I said, "You damned fool," (I knew him pretty well) "we haven't played them but once since 1900, up to which time we had never beaten anybody, and on that occasion we tied them." I went on at some length, but right here Dr. Yellowlees' theory found confirmation. My friend remained as impervious to reason as only a lawyer or judge can be. He was utterly unconvinced and went off moaning about the jinx and cuddling his bottle of gin.

In the second half things went badly, not by luck but because we didn't have the stuff. Black, a truly great plunging back who had been mainly responsible for our first touch-down, was out - he had a weak knee - and our defense and offense were mediocre. Yale quickly earned a touchdown, tying the score at 7-7. It remained this way until late in the game when we tried a pass. A Yale substitute blithely pushed the intended receiver, grabbed the ball and ran deep into our territory. None of the officials saw the infraction, and there was no penalty. Our defense collapsed, and they scored the winning touchdown. Push or no push, we were outplayed, and the best we could have hoped for was a tie. Any attempt to find a jinx in this game ought to be a failure.

Came 1927, and we had an excellent team, although light in the line. Only one starter there weighed over 185, and none as much as 200; also we were short on reserves. We had beaten Harvard 30-6 the week before the Yale contest. But we met the Bulldogs in not-too-good shape and with our light line tired from the heat of the day and the previous Saturday's explosive effort. Yale, on the other hand, had a heavy line, a fine team well fortified with reserves, and was in excellent condition. True, they had lost one game that year to a powerful Georgia eleven, much further advanced than were the Yale Bulldogs when the game was played. I remember distinctly three things. First, we were fairly outplayed, especially in the line, and the 19-0 score was a just index of the relative merit of the teams on that day. Second, I remember the heat which beat down on players and coatless spectators all through the afternoon. On the rare occasions when a cloud drifted over the sun, it was as though someone had slammed shut a furnace door so that the blast of heat no longer struck one in the face. Finally, I have a vivid recollection of a friend possessed internally and externally of vast quantities of gin, and a brand-new, expensive wrist watch. During a time out, one of those rare silences fell on the Bowl. He glanced at his watch and found it had stopped. He immediately arose to his feet, glared about him, then, raising his hand with the wrist watch for all to see, in stentorian tones he anathematized the offending timepiece as follows: "Damn you, in front of 70,000 people you had to fail me!" He then sat down.

1928 found us playing in a dismal rain with our Ail-American back, Al Marsters, out of the contest, as well as Captain Black. We were outplayed and outscored 18-0 by a better team. This may be as good a time as any to dispel the illusion that Dartmouth has repeatedly journeyed to the Bowl with a terrific undefeated eleven, only to lose to a mediocre Blue unit. Actually, I expect to show we have won more often as underdogs than has Yale and that the heartbreak games have generally gone our way. Also, the belief in the irresistible Yale second-half comeback against us should pass into the realm of shades. The facts demonstrate that it is the Indian who, as the sports writers put it, has "roared from behind" to win more often than the Bulldog.

1929 is perhaps the year most often cited as "proving" the existence of the jinx. Our final record that year was seven wins and two losses, and we had a grand team. So did Yale, which lost only one Ivy League game to their Nemesis, Harvard, led by the redoubtable Ben Tichnor, who balked the Bulldogs by grabbing their great back, Albie Booth, by the collar of his jersey instead of foolishly trying to tackle him.

The Dartmouth-Yale contest, aside from the usual bleatings about the jinx,, was heralded as a great individual battle between Booth and Marsters. This was rated about even, as was the game, with each warrior claiming his adherents. The first part of the struggle was all Albie's, as he ran well and connected on a field goal which, along with a touchdown, sent his team into a 10-0 lead, while Marsters was stopped cold.

Came the second half and things changed. Marsters went berserk and passed the Yale team dizzy for a score which made it 10-6, since our try for a goal failed. We kicked off to Yale and someone tackled the receiver so hard that they heard the crash in New Rochelle. We recovered the inevitable fumble. Marsters again took over, and in one of the greatest exhibitions seen anywhere, any time, bulled through for a second touchdown. For the first time in the game, we went ahead, and the stands were roaring. Shortly thereafter Marsters was accidentally kicked in the back and Harry Hillman, our trainer, noticed that Al was dragging one leg. He was removed from the game and from football forever, as it was discovered that his back was seriously injured. In spite of this, things went pretty well.

Late in the fourth quarter, we penetrated deep into Yale territory. The going got tough and Tommy Long-necker, calling signals, on Yale's 25-yard line chose a down-the-middle pass. I am not a football expert, but I have heard such defend this call, and for what it is worth, I agree. The pass as planned, had it been successful, would have put the game on ice, and had it been intercepted, it would normally have been at least as good as a punt and would have offered little chance for a runback. Unfortunately, Tommy, rushed by the Elis, slipped just as he threw, and the ball went wild Into the hands of one Hoot Ellis, who, as Bill Cunningham described him, was standing idly to one side, "cleaning his fingernails." Aside from his fondness for cleanliness, Ellis had another virtue (doubtless he had a lot, but I am only interested in this one) - he could run, and he did. Dartmouth hearts sank as he ran, and the jinx waxed fat. However, actually it was only one of "those things" such as happen time after time in football, and for my money one bad break does not make a jinx any more than one swallow makes a summer. However, Yale 16, Dartmouth 12 was the way it went into the books.

When 1930 rolled around, we had another first-class team and so did Yale. The two battled it out to a 0-0 tie, and no untoward incidents occurred, except that Booth ran for what would have been the winning touchdown, but was called back on a penalty. Incidentally, Yale outplayed us badly in the first half. (Query: Where was the jinx then?)

The 1931 contest between the two schools was one of the most famous and exciting ever waged anywhere by any institutions. Our team was not one of our best; we were defeated that year by Harvard, Columbia and Stanford. Yale, on the other hand, had a great team. They beat Barry Woods' previously undefeated Harvard eleven (conquerors of Michigan) 3-0; Princeton, 51-14; and generally went to town. At half time, they appeared to be making mincemeat of us and led 26-10. Later they made it 33-17. Here was the Big Blue favored team and the Big Blue jinx in complete control. How could this combination possibly fail to win? Yet, mirabile dictu (Pop Clark, Latin teacher of the Phillips Exeter Academy, wherever you are, aren't you ashamed now for flunking me in Latin?), Yale did not win. We tied it up, and at the finish the Big Blue team, the alleged Big Blue jinx, and the spectators were limp. Only the Dartmouth eleven was still rampaging and confident that, given a few minutes more, the score would have been Dartmouth 40, Yale 33. Wild Bill McCall in our backfield truly lived up to his name, as with runs of 93, 65, and 51 yards he dumbfounded the Yale defense. On one occasion, his confident exuberance was such that as he crossed the goal line, he held the ball high in the air in one hand, twirling it on his fingers. There are those who claim to have seen the jinx that day - and that he was wearing a green jersey.

In 1932 we had a weak team, losing every major contest. Yale had a pretty fair eleven, and in one of our better games of the season, they squeaked out a 6-0, but nevertheless deserved, win.

In 1933 it was the same story. Football was on the toboggan here, and while we beat Norwich, Vermont, and Bates, we ended the season with a 4-4-1 record and a royal 39-0 shellacking by Chicago. We lost again to Yale, 14-13.

1934 brought Earl Blaik & Co. to Hanover, along with a change of climate. Blaik's philosophy was simple, as are most good things: "The Yale jinx is nonsense. When we have a better team, a better disciplined team and make the fewer mistakes, we'll win." He was to give dramatic and conclusive proof of his words during his stay here. Not counting his first year, with which it is hardly fair to charge him, his record against some of the best and luckiest teams Yale ever had is four wins, one loss, and one tie. In '34 he started with little or nothing except his own abundant skill, spirit and will power, and that of his assistants Ellinger, Gustafson, Donchess, and trainer Harry Hillman, the veteran track coach. I remember going down to the gym one day, and Blaik and his staff were even having to teach our boys how to run, which is some indication of how far we had to travel. Anyhow, spirit improved, and so did the team.

Yale had a fine team that year big, tough and loaded with such great competitors as Lucky Larry Kelly After an early season loss at Columbia the Blue really rolled, defeating every Ivy League opponent, including a fabulous Princeton team which was supposed to disembowel the Elis. Yale scored in the first half against us on a series of plays featuring what was then known as the "shovel pass," a sort of screen pass. Came the second half, and Dartmouth began to press. Outmanned and outweighed, we yet forced the Bulldog to fight for his life. We scored a safety and kept the steam up right to the finish, but the Elis' defense was too good and we couldn't put over the winning touchdown. The figures 7-2 are a fair index of the merits of the teams. There was the usual moaning about the jinx, but it had no more foundation in fact than a rumor that the author of this article is a great mathematician and can show up Professors Bancroft Brown and John G. Kemeny any day.

Now we come to 1935, Blaik's second year. The lone addition to his staff was Rollie Bevan, long-time high school coach-trainer par excellence from Dayton, Ohio, Blaik's home town. The great day came at last and all Hanover started for New Haven. It had rained heavily during the night and was still at it in the morning. I remember on the way down the rushing brooks and the dank November forests as we rode along. On nearing New Haven, the wind began to pull the clouds apart, blue sky appeared, and the rain slackened. We came through Cheshire, Connecticut, where our team had stayed at the Academy overnight, just as our boys were getting into the buses on their way to the Bowl. They looked, somehow, rather small and young and pale, and perhaps my heart sank a bit. A short time later, just outside the Bowl gate, I saw old Judge George M. Fletcher, father of a Dartmouth son and one of the most rabid Green rooters ever to draw breath. Though about 85, he was still vigorous, and he stood there with the pork-pie hat he always wore tilted back and jammed down over his ears. He was chewing gum furiously, and it seemed his little white mustache was quivering and leaping up and down with every chew. He looked cheerful and confident, and my courage was revived. I will not detail the play-by-play events of that memorable afternoon; they are familiar to thousands of us. Sufficeth to say that in the first half, led by our senior halfback, Pop Nairne, we drove for an early touchdown and picked the point after. Pop must have taken a good dose of hormones for the occasion; he was terrific. The score board read 7-0 at half time. Came the second half - and it did not seem that seven points would be enough. With Lucky Larry Kelly and the truly great Clint Frank on the roster, aided of course by the jinx, a Yale win seemed probable to the Yale stands and the faint hearts in the Green sections.

Shortly after the second half got under way, we punted. Charley Ewart, the Yale quarterback, a little cuss but fast and a fine money player, grabbed the ball on the left side of the field and set off. It was a grand run. He tore down the sidelines, dodging and twisting, and then suddenly cut to his right. Somewhere around the ten- or fifteen-yard line, John Handrahan's body lay out flat in the air as he dove to stop Ewart. It was no use, and the rising roar from the Yale stands seemed to split the sky as Charley crossed the goal line. They missed the point after, Tom Curtin's attempt hitting the cross bar and bounding back instead of over, but they were not done. The Bulldog drove and passed and at last came deep into our territory. Then it was that the discipline and drilling of the Blaik regime paid off. Perhaps, too, the carnation which Blaik's attractive wife had given every Dartmouth player before the game helped - never underestimate the power of a woman! Anyhow, we held. It was fourth down, somewhere around our 25- or 30-yard line, and a long way for Yale to go for a first down. They appeared to be getting ready for a field goal, or at any rate it did not look as though they were going to run for it. The ball was snapped, and somehow got lost in the Yale back-field. It was the famous "Dance Play," borrowed from Columbia, and it almost did the trick. The Dartmouth team was running around in circles, trying to find the carrier, and suddenly a blue-jerseyed figure who had been mingling sociably with our boys, darted out of the group and set sail for our goal. The name of the hero who stopped him is reported to have been Whitaker, and he saved the day. Still it looked like a first down, and all the Bowl was still as the chains were stretched. (Oh, for a few extra links!) Players and officials bent over the ball, and all at once a green-shirted player began to jump up and down, and I knew we had it.

However, the ball was about on our eleven-yard line and we were still in a pickle. The Dartmouth team and Hollingworth took care of this when he made a brilliant run out to our 33. But we needed another touchdown to be safe, and it was hard to come by. We pushed deep, but we couldn't seem to shove it over. However, we kept Yale penned in and they were getting desperate now. They tried pass after pass. Finally, at an unlikely moment, Kelly shot through our line, cut to the right, and in a flash was behind Eddie Chamberlain (now Director of Admissions), for what I believe to be the only time that day. He was traveling full speed, and as he twisted and leaped, the ball went just off his fingertips. Had he caught it, he would have gone all the way and put Yale ahead at this late stage in the game. As the ball bounced along the ground and Kelly walked disgustedly back to the line of scrimmage, I saw the jinx in a bright green jersey, grinning.

It remained for the son of a Yale man to sew up our first win over his father's team. Why is it Yale men seem to do so well after they leave New Haven? Look at Eleazar Wheelock. Becoming dissatisfied with what he experienced there, he founded Dartmouth. Look at Mutt (Carl) Ray's father. After his graduation from Yale, in due time he gave us Mutt. I say both Eleazar and Dr. Ray did all right.

But getting back to the game, during all the afternoon Mutt at center had been a Trojan on offense and defense. A firm and determined character, neither Lucky Larry Kelly nor Clint Frank nor any phantom jinx overawed him. He had one consuming desire to beat Yale. Now, with the Elis frantic, his chance came. Gambling against odds - and they had made this pay off many times — Yale passed from around their own goal line. Our ends, especially El Camp, had rushed the passer furiously all afternoon, and this time was no exception. The ball shot toward the intended receiver in our left defense zone, but it never reached him. A pair of hands fastened to bare washerwoman's arms - for Mutt had his sleeves rolled up plucked the ball out of the air, and Carl Ray started for the goal, some seven or eight yards away. Squarely between him and his objective were three Elis. "He can't make it," I thought, for it appeared as though he had no more intention of changing his course than a comet. In this case, appearances were not deceiving. Scorning the craven subterfuge of dodging, straight for the three he charged, and they met him on about the two-yard line. They should have thrown him back, or at least dropped him in his tracks. Nothing of the sort happened. Defying all laws of God, man and physics, the green shirt bore right on, and the mass went down in a sprawling heap across the goal line. Iron Joe Handrahan, at guard for us, put the ball between the posts as coolly as though we were practicing on Memorial Field, and that was it.

The clock moved and the final minute came. Onto the field at both ends surged the crowd. Neither officials nor police could stop them. Down came the goal posts, but play continued around midfield while the yelling mob danced, howled, and jovially blackened each other's eyes as they fought for fragments of the goal posts. My last vivid recollection of this game is of two gentlemen (I suppose they were such) who leaped over the parapet at one end of the Bowl and kept their legs churning all the way down as they sailed through the air, so that when they hit the ground they shot toward the gridiron without an instant's pause.

It may be opportune now to state that history discloses another fact which lends weight to the existence of a Green jinx. Almost coincident with Blaik's arrival at Dartmouth, there entered Yale two of the greatest and altogether most formidable All-American players ever to wear a blue uniform. Lucky Larry Kelly, an end, entered in the fall of 1933, and Clint Frank, a back, in 1934. These two were the bane of every college team they met - except one. They pulled out of the fire game after game that appeared hopelessly lost, such as their 26-23 win over a great Princeton team in 1936, after Princeton had led 16-0. They did this against every team except one. For the first time in years, Yale had an undefeated eleven in the making in 1936, and it remained undefeated except for one game. You've guessed the answer. Of course the one team against which neither Kelly nor Frank had any luck was Dartmouth. Kelly played in only one winning game against us in four years (his freshman team lost to ours, 13-0), and Frank never played on a winner against us.

The year 1936 was a remarkable one in football. Yale, led by Kelly and seconded by Frank, was mowing down all opponents. Against such rugged opposition as Navy, Penn and others, Kelly or Frank saved the day. The Bulldogs seemed invincible. It was in this atmosphere that once-defeated Dartmouth traveled to the Bowl to meet undefeated Yale. The win in '35 seemed something of a fluke to the jinx cult and all the press, aided and abetted by some Dartmouth men, beat the drum for the jinx to reassert his ancient and only-once-broken mastery. There was one group where this idea put down no roots. This was the Dartmouth squad and coaches. Tough, disciplined and determined, this superbly drilled team feared neither Kelly, Frank, nor the devil in the form of the jinx or otherwise. They proceeded to demonstrate this on the field. All the first half they smothered Kelly and Frank, used to bowling over opponents, went down before our tackles as though his legs had been cut from under him by a scythe. With the contest pretty well along, we led 11-0 on a touchdown and two safeties - for the Blue defense was tough.

Then things happened. They began calling pass interferences against our defense. Yale got a touchdown. Now with the Bowl rocking, the Bulldog, under the invincible leadership of the officials, launched a mighty drive. We could still stop Frank. We could cover Lucky Larry, but to no avail. Each time the ball was batted from his out- stretched hands, fate in the form of an official marked the spot and the linesmen jerked up the stakes and ran on. The climax came when the Elis stopped cold by our defense, were awarded the ball, according to Dartmouth tackle Dave Camerer, on our one-foot line on an interference call. The eager beaver operating the scoreboard flashed up: "Yale 13 - Visitors 11." He was, as lawyers say, "in error." A Dartmouth back, tried beyond endurance, slammed his head guard to the ground and started off the field. Rollie Bevan, cursing but calm, shoved him back.

The teams lined up and, as Camerer describes it, from the Yale stands "came a sound like a pounding surf." There was ample time for two plays, and all the Blue had to do was to score and win the game. How could they miss? Kelly, Frank, the jinx, a foot to go, the Dartmouth boys demoralized by the change in fortune - the game was won. Such were the thoughts which flashed through the minds of scores of thousands in the Bowl. But there were a few who entertained no such ideas. They were the Dartmouth team as they lined up to await the assault.

Yale, wisely figuring that they could not score a touchdown on a penalty, chose to send Frank into our line. They might as well have tried to send him through the armor plate of the battleship Missouri. As Camerer puts it, Frank was "up and over and into our arms." He had not gained an inch. The roar from the Yale stands began to die down as the sound of water when the flood gates are being closed. All the Bowl was standing as the teams crouched for what everyone knew would be the last play. It was a good play - Lou Little's K-79 which had won the Rose Bowl game for an undermanned Columbia team against Stanford in 1934. It was well executed - Hessberg, the fastest man on the Yale team and probably on the field, was to sweep our right end for the winning touchdown. At the start of the play, everything went perfectly. The deception was good, all the boys in Blue performed their assignments, and the hand-off to Hessberg, some four or five yards back of the line, was lightning quick. Then it happened. Flying through the air with the greatest of ease came a Flying Dutchman, Pyrtek by name, our right end. All week long Blaik had drilled Pyrtek to defend against this play, and every time it had been run in practice, Pyrtek had been fooled; but now the jinx was plucking his elbow. Pyrtek hit Hessberg, Hessberg hit the ground some yards back of the scrimmage, and the hands of the clock touched zero. The Yale stands sank back in silence, and now from the Dartmouth section came a pulsing thunder pouring up like flame-driven smoke. It only remained for Mutt Ray, taking no chances now with the officials, to grab the ball and dash off the field. The crowd swarmed from the stands, but just before the north goal posts went down a phantom figure appeared, perched grinning astride the crossbar - and the jersey he wore was green.

In a faraway city, huddled by his radio, sat a member of the Class of 1929 who shall be nameless. I will only state that ordinarily he possessed more than average intelligence. As the ball moved over nearer the Dartmouth goal on call after call against us for interference, the anguish of this '29er increased, and he writhed and twisted in his chair. At last when the announcer bawled, "IT'S YALE'S BALL FIRST AND GOAL TO GO ON THE DARTMOUTH ONE-FOOT LINE!" the limit of the '29er's endurance had been passed. Leaping from his chair and calling down blessings from heaven upon the heads of the officials, he dashed into his bathroom, slammed the door, flushed the toilet and turned on all the water faucets so that the hateful voice could no longer reach his ears. It never occurred to him to shut off the radio.

His wife, however, showed sterner stuff and stuck it out to the not-so-bitter end. She brought her gallant spouse back to life and hope by yelling at him, "Shut off that water, you damn fool, and come out of there! It's over and we won!"

In 1937 both Dartmouth and Yale had top teams. Both went into the game undefeated, but Yale looked like a pretty sure bet because the Dartmouth team, almost to a man, had been stricken violently ill beginning Thursday night before the contest with food poisoning — or maybe it was what we used to call "summer complaint," though it was November. Now they were wobbly and weak from the effects and nobody expected them to be able to stand up during a tough game. Yale was almost a 2-1 favorite - the odds were 8-5.

Every seat in the Bowl was taken and thousands stood outside, listening to the tumult created by another ring-tailed snorter of a contest. In the first half, Yale pushed us about some, but couldn't seem to shove over a touch-down. Our line, with one or two regulars out and the others at sub-par, comprised, as Bill Cunningham described it, a lot of birds "named Joe," but it seemed to have what it took in the clutches. Gus Zitrides at guard, weighing all of 170 pounds unpurged, must have imagined himself back at Thermopylae and that Clint Frank & Co. were Persian warriors. They did not pass. However, the Elis got a safety and, leading 2-0 at the beginning of the second half, seemed in the circumstances a sure-fire prospect to win.

They couldn't gain through our line, valitudinarious (look it up) though it was, so they began throwing passes. Bob MacLeod, Ail-American halfback, intercepted one on our fifteen-yard-line and went all the way. In his weak condition, he was so exhausted he had to lie down after the touch-down. We missed the point and the score was 6-2. Then Hutchinson, almost as good a back as Bob, ran 55 yards with another interception, deep into Blue territory. Our sick boys came to life and proceeded to shred the Yale line for a touchdown. However, on the scoring play one of our linesmen was detected offside. Candor compels me to admit he was at least a yard beyond the line of scrimmage before the ball was snapped, so we were justly called back and penalized. On the next play, we made one of the few field goals Blaik's teams ever kicked. It was lucky we did, for in the flurry of last-minute passes, on a Frank-to-Hessberg toss, Yale tied up the ball game 9-9. This was not too unfair a result, although hard to take considering our gallant effort.

I skip lightly over the next few years. Even the most active and morbid imagination can find no Blue jinx in our 1938 win of 24-6, our 33-0 victory in 1939, or our 13-7 loss in 1940. In 1941 we won 7-0 and in 1942 a mediocre Dartmouth team lost to a pretty good Yale team 17-7. In 1943 we took them to the cleaners 20-6. From 1944 through 1946 inclusive, we won only six games in all, or an average of two games per year. Yale, with a team undefeated in Ivy League play in '44 and better-than-average teams in '45 and '46, deserved to beat us and did, though we held her to 6-0 in '44 and '45, which were about the best showings, relatively speaking, that our team made at any time during those years.

In 1947 we were still not strong, with a 4-4-1 record, but again we gave the Blue a good game before yielding 23-14, after we had come back strong in the second half. In 1948 came the deluge, with Tuss McLaughry taking a fine team into the Bowl. The scoreboard read Dartmouth 41, Yale 14; and in '49 we did about as well, beating them 34-13. In 1950 we won 7-0 in the rain, rather to the surprise of the small crowd, since the Elis were favored. In 1951 came another thriller. Yale topped us 10-0 at the half, and with Spears, their captain and great plunging back, they seemed set for a decisive victory. But again, for those who wish to believe it, the jinx appeared and again he was wearing green. Beginning the second half, we drove for a touchdown and made the score 7-10. It was raining and snowing hard, and the deciding play on which our quarterback, Gene Howard, broke through the Bulldog line and went some sixty yards for the winning score, has been set to poetry, though not to music. It goes like this:

He breaks through the line, Just watch him go Like a bat out of Hell Through the rain and snow. The Elis chase him But they're too damned slow. Our blockers sock 'em And lay 'em low. The stands are howling Go! Go! Go! Here's where we make it Four in a row, For the jinx wears green In New Haven.

Near the end of the game Yale, with Spears the workhorse, launched an attack which went to our eleven-yard line and seemed destined to go all the way. But with second down and only about five yards to gain, a hand off was fumbled in the Yale backfield, and it was third and eleven. The Blue tried two passes, and an alert defense spoiled both. We took the ball around our fifteen-yard line. Deep thought was given by our quarterback to each remaining play, though not quite deep enough for us to be penalized. A Dartmouth back, jumping up and down and waving his arms, together with an official, signaled that the game was over. We had taken four in a row from Yale.

In '52 and '53, with weak material, the pernicious anemia which had afflicted our football fortunes - and which at some time or other happens in every school — permitted us to win only two games each year. One of these in 1953 was against a good and previously undefeated Yale squad which was a prohibitive pre-game favorite. Up to this contest, we had won no games that year - in fact, we were riding a losing streak never exceeded in our history - and Yale had lost none, so it was a confident group of Bulldogs that took the field against us. But 10, the poor Indian came to life. Before an unbelieving throng, he proceeded to score touchdown after touchdown in the mellow sunlight of an Indian Summer afternoon. The final scoreboard flashed out: Dartmouth 32, Yale 0!

I have it from an unimpeachable source that after the game a pretty girl in blue - obviously a Yalena - came into the ladies' powder room, sat down on whatever it is ladies sit on in ladies' powder rooms, and gasped out, "What happened?"

In 1954 and 1955 we did not have strong teams, winning only three games as against six losses each year. The Yale victories by better Yale teams, of 13-7 and 20-0 respectively, were earned.

In 1956 Yale had one of her best modern teams. She was loaded with talent and won every Ivy League contest. We played them with a crippled aggregation and made a creditable showing, the score being 13-0 until near the end of the game when, a justifiable Dartmouth gamble failing, Yale scored again.

Came 1957 and both schools were strong. Yale, after a slow start, was beginning to hit the stride which carried her to a 20-13 win over a tremendous Princeton team, and a Big Three title. We were badly handicapped by the absence of Burke, our best defensive halfback, lost in the Harvard game. Several key players were below par, and the team, which had had a rough week with exams, appeared tired. In the second period we scored a touchdown on a pass and led Yale 7-0 at the half. The second half, except for an amazing display of courage and skill by the Green in the last two minutes, was all Yale. They scored two touchdowns, earning both clearly, and led us 14-7 with less than two minutes to go. We hadn't been able to gain much all day and had been completely bogged down all the second half. Up to the last two minutes, I believe we had completed just one pass out of ten attempts. In these circumstances with the mighty Yale team and the mighty Yale jinx against us, what could we do? However, we took the ball on the kickoff, rang up three successful passes out of four attempts and went all the way to tie up the game with just six seconds left! In the contest Yale made sixteen first downs to our nine, outgained us 220 yards to 84 on the ground, and up to the last two minutes was about even with us in passing yardage. She even outdid us in penalties, losing 35 yards to our 10, and one penalty on her was costly. If anyone can find a Yale jinx that day, he will have to look through blue glasses.

1958 is too fresh to require a detailed summation. Sufficeth to say that in spite of a weak team, Yale, in good condition and fresh from a win over Colgate, had a golden opportunity to knock us out of the Ivy League championship which we eventually won. We played the game literally on one leg. Of the first-string or alternate players, ends Palmer, Hibbs and Hanlon were out. So was Bowlby at tackle. Bob Boye at guard hobbled on one leg much of the second half, but he had to keep hobbling, as Clark, his replacement, was hurt and forced to leave the game. Jake Crouthamel was injured late in the first half and saw no more action, but rested his sore hip by hopping up and down the side lines and yelling exhortations at our team. Bathrick, though he played, still favored his knee hurt in the Brown game. On top of this, we had just lost hard and discouraging battles to Holy Cross and Harvard on successive weekends by 14-8 and 16-8 scores. We were indeed ripe for the plucking, but we clung to the fight for a 22-14 win and went on with indomitable spirit under the superb coaching of Blackman & Co. to become Ivy League champions for the first time in twenty years.

Well, this brings us almost up to date. Now, as I write on the last Saturday afternoon of October 1959, we have won but a single game in five attempts, while Yale in an equal number of contests is unbeaten, untied, unscored upon, and seemingly unstoppable. Just now I am told she is leading us by the comfortable margin of 8-0 at half-time in the mud and rain in New Haven. It's too bad - the boys have tried hard and had a lot of tough luck, but I guess we'll have to scratch off 1959 Hold it! What's this blasting out over my radio? "Singleton's pass falls in the mud, incomplete, and it's Dartmouth's ball first and ten on her own 31-yard line." Now the roar becomes deafening, and I have a hard time to catch the announcer's words: "The clock is stopped with only thirty seconds left in the game. Dartmouth is lining up - regular T formation. There goes Gundy straight ahead for a yard or so. The clock is running now. They're waving white handkerchiefs in the Dartmouth section at the Elis and they're counting the seconds."

"Twenty-three, twenty-two, twenty-one -"

"The Dartmouth team is huddling back on their fifteen-yard line."

"Sixteen, fifteen, fourteen - "

"It doesn't look as though there'll be time for another play."

"Ten, nine, eight —. " Louder and louder swells the rhythmic roar of the chant.

"The team is walking up to the line of scrimmage."

"Four, three, two, one!"

The chant breaks into a thunderous crescendo of sound, but somehow the announcer's voice comes through - "Final score: Dartmouth 12, Yale 8, and Dartmouth wins the game!"

So go ahead and play with the jinx all you wish, have a picture of him framed and hung in your living room, but don't forget in your color scheme that the jersey he wears is green!

Dartmouth rooters breaking up the goalposts after the historic gridiron victory in 1935.

In the 1935 Yale game, Frank Nairne '36 carries the ball on a devastating deep reverse, the play in which, claimed Yale's president, the whole Dartmouth student body came down out of the stands and ran interference for the ball-carrier. Jack Kenny (15) and Joe Handrahan (73) are blocking out Larry Kelly, while John Handrahan (21), Latta McCray (74) and Eddie Chamberlain (17) form a wall in front of Nairne.

Throughout the 1930's the Dartmouth-Yale game was invariably a thriller and thisview of the packed Bowl in 1937 is typical of the crowd always on hand to see it.

About the Author AMOS BLANDIN '18, a resident of Hanover for the past nine years, is Associate Justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court. He assumed that post in 1947 after being a Justice of the State Superior Court for six years, the last two as Chief Justice. A native of Bath, N. H., he holds Dartmouth's honorary LL.D. degree (1951) and has lectured in the Great Issues Course. In recent years he has regularly dropped by the ALUMNI MAGAZINE office to read the sports section of the Yale Alumni Magazine — which we interpreted as an eccentric form of judicial relaxation. Now we know it was research all the time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Leadership

November 1960 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

Feature"The Era of the Shrug"

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleEvening Assembly

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleSecond Panel Discussion

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleFirst Panel Discussion

November 1960

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSnow Engineer

FEBRUARY 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Library Culture

December 1992 -

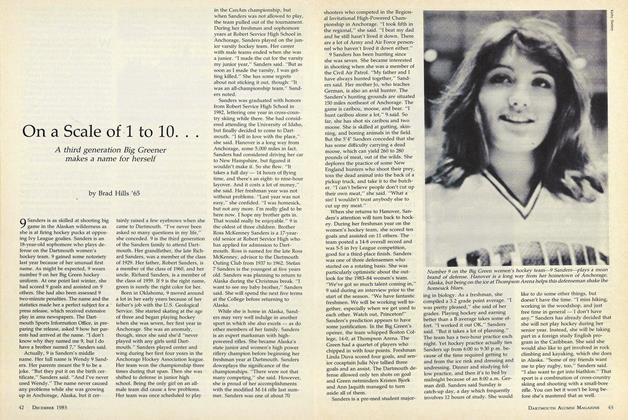

Feature

FeatureOn a Scale of 1 to 10...

DECEMBER 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

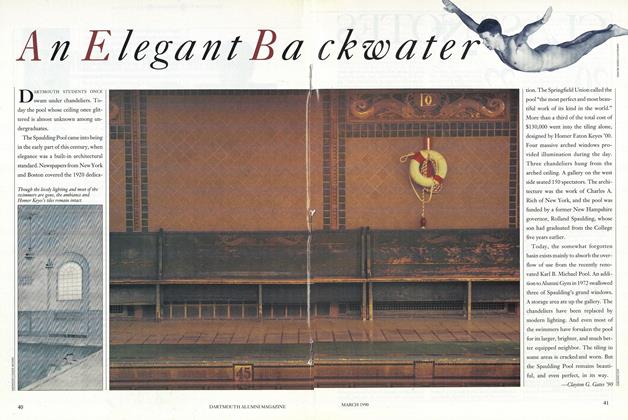

Feature

FeatureAn Elegant Backwater

MARCH 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

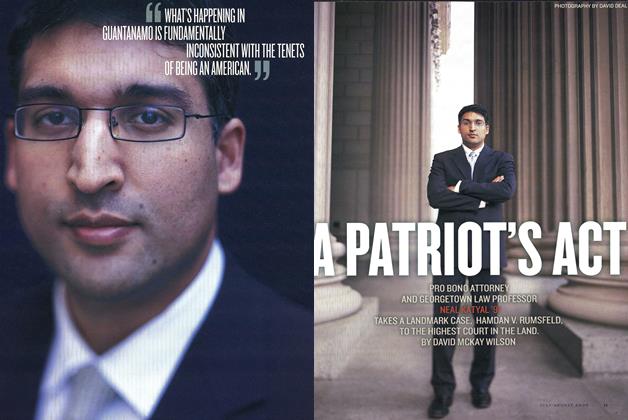

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July/August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Cutting Edge

May/June 2011 By JULIE SLOANE ’99