By Elliot R. Goodman '45. NewYork: Columbia University Press, i960. 512pp. #6.75.

As Philip E. Mosely observes in his Foreword to Professor Goodman's study, it "fills a serious gap in our studies of Communist theory and Soviet policy" since the doctrinal pronouncements on the Communist world order, which orthodox Marxists assume to lie ahead, have "oddly enough ... not previously been examined with all necessary care" (p. xiv). They now have been, and Professor Goodman can be assured of the gratitude of many students of Soviet affairs who have long awaited a study of this sort.

Professor Goodman's book consists of what might be called variations on a single theme. The variations are of great interest in themselves, quite apart from their bearing on his thesis. They include, for instance, a searching analysis of pre-1917 Marxist writing on the coming world state - an analysis which, not surprisingly, yields the author his most unequivocal evidence of the Marxian objective; a discussion of the impact on the world state idea of "socialism in one country," "united front," "peaceful coexistence" and other formulations required by the exigencies of national politics and Soviet isolation — an impact which altered the original idea only by the addition of a word: a Russified world state (p. 128); enlightening discourses on the Soviet notion of sovereignty and on the role of war in bringing on the world state; an excursion into the threat to Soviet hegemony within a world state posed by Communism in Asia - a threat which the author seems curiously to minimize as likely to alter the image of the future; and, as might well have been expected, a full inspection of the "withering away" concept, studied in the context not so much of the Soviet state but of the world state.

These are a few of the variations. The theme, which Professor Goodman urges more strenuously than most students of the USSR have urged it in recent years, is implicit in the title of the book itself.

One question that occurs to this reviewer is why the author so persistently stresses a world state as the main Soviet objective and not world revolution. This would seem to be reversing the true order of things, for surely the organization of society after revolution depends on too many unforeseen variables (such as the course of Communism in China) to permit any very concrete "design." Strategies aimed at bringing 011 revolution, on the other hand, are capable of "design." Just as pre-revolutionary Bolsheviks seem in retrospect to have devoted their attention to the seizure of power, and only incidentally to have considered the shape of the society to follow, one can imagine today's leaders in the Kremlin concerned less with the form of a world state than with the revolutions that must precede it. To this reviewer it appears that the author, in making a world state so explicitly the objective of Soviet policy, limits himself too much to an arena that is at best speculative, to Russians and non-Russians alike. The hard, real world of practical revolutionary politics, which is our day-today concern, is left somewhat aside.

Whether or not one agrees with the particular focus Professor Goodman gives his study, however, there will be little disagreement that his painstaking research in a neglected area makes a significant contribution to contemporary scholarship on world Communism.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Disinterested Citizen and the Maintenance of Freedom

July 1960 By WHITNEY NORTH SEYMOUR, LL.D. '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1960 By ANDREW J. SCARLETT '10 -

Feature

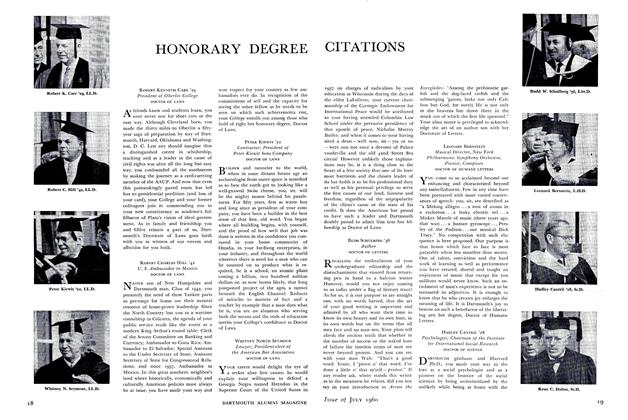

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1960 -

Feature

Feature1960 Commencement

July 1960 By D.E.O. -

Feature

FeatureThe Image of the Educated Man

July 1960 By HARRISON CASE DUNNING '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1960

CHARLES B. MCLANE '41

-

Books

BooksROOSEVELT AND THE RUSSIANS

December 1949 By Charles B. McLane '41 -

Article

ArticlePasternak and the Russian Community

JANUARY 1959 By CHARLES B. McLANE '41 -

Books

BooksNO SUBSTITUTE FOR VICTORY.

DECEMBER 1962 By CHARLES B. McLANE '41 -

Books

BooksJUSTICE IN THE USSR:

MARCH 1964 By CHARLES B. MCLANE '41 -

Books

BooksSOVIET CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE: THE RSFSR CODES.

MAY 1966 By CHARLES B. MCLANE '41 -

Books

Books"A Mess of Russians"

OCTOBER, 1908 By Charles B. McLane '41

Books

-

Books

Booksshelf life

Mar/Apr 2002 -

Books

BooksTHE PATRIOT

January 1961 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Books

BooksTHE CAP'N'S WIFE,

March 1947 By George C. Wood -

Books

BooksA NAVAL LOG,

October 1945 By Homer Howard, Lieut. Comdr., USNR. -

Books

BooksSPIKED BOOTS: SKETCHES OF THE NORTH COUNTRY.

November 1959 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Books

BooksRUDOLPH THE RED-NOSED REINDEER SHINES AGAIN.

November 1954 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26