PROFESSOR OF RUSSIAN CIVILIZATION

THE Pasternak affair has been on many minds in recent months and will not soon be forgotten. I think the episode met a need in the United States. It came at a time when for more than a year the news out of Russia had been too good for our peace of mind - sputniks, alleged educational accomplishments (alleged, incidentally, much more noisily here than in the Soviet Union where the entire educational edifice has been undergoing an agonizing reappraisal), and, as usual, continued success relative to ours in diplomatic gambits. It was therefore comforting to have world opinion reminded - we, of course, knew it all along - that persecution of non-conformity is a more enduring characteristic of the Soviet system than a show of free competition in the world of ideas and values.

This sense of relief is natural enough and, all things considered, not a wholly unworthy emotion. But it has made more difficult a dispassionate evaluation of Pasternak's controversial book as a work of art. The fact that few here had heard of Boris Pasternak prior to the publication of Doctor Zhivago last summer (despite the recognition long since accorded him outside the Soviet Union as one of the foremost Russian poets of this century) is far less disturbing than the general unwillingness, with the book now before us, to judge it except in a purely political context.

A colleague whose perception in literary matters I generally respect recently expressed the view that it was not really necessary to trouble with Zhivago, was it? In a season so crowded with other talent - like "that other Russian," as he called him, Lolita's Nabokov - there was hardly place for a Russian martyr whose notoriety sprang from the proffer, and his rejection, of a Nobel Prize.

The difficulty Americans have with Pasternak, even when they try, is one of access - access to his rich but immensely involved language. It is generally recognized that the present American edition of Zhivago is an inadequate translation, but it is also true that no translation of Pasternak can be entirely adequate. For he is a poet, and a particularly difficult poet, despite the fact that he has described Zhivago, whimsically, as a "novel in prose." Small wonder, then, that many honest citizens who have read the American Zhivago conscientiously have been puzzled by the acclaim it has received. So far as the Nobel Prize is concerned, they have murmured "Politics!" (murmured so as not to be mistaken for Soviet pundits who of course are saying the same thing). Others, searching further for the greatness, have attempted to locate it in Pasternak's continuation of the tradition of War andPeace, a vast Russian panorama "in the old manner" against a background of war and social upheaval. But Pasternak is only incidentally concerned with these matters. So little is he preoccupied with the Revolution, for instance, that the reader with even modest knowledge of chronology is hard put to say at what juncture in history this or that episode in his narrative occurs.

Not revolution, but the impact of revolution on man, and more particularly the capturing of the transformations which arise from this impact in a prose that has few peers in the Russian language - this is Pasternak's business. To Soviet bureaucrats the infuriating thing about Pasternak, in Zhivago as in all his work, must be not that he is hostile to the Revolution - this they could deal with - but that in a deeper sense he ignores it. This in Russia is unpardonable.

It must be obvious then that a proper review of Zhivago is a very exacting and scientific exercise, far beyond the scope of these brief observations and beyond the capacities of the present writer, a political scientist. To qualify, one should be versed in symbolism, in Joyce and Proust (despite the fact that Pasternak has evidently turned to Proust only in recent months), and in the entire evolution of modern Formalism. Zhivago is a book in this tradition. To seek mere entertainment in it, larded perhaps with a vaguely social message, is to miss the whole point of Pasternak's effort.

No writer, not even Pasternak, can be judged wholly outside his times and his community. It is currently fashionable, of course, to picture Pasternak as an indomitable David living in splendid aloofness and disdaining modern Soviet Goliaths such as Surkov (head of the Writers' Union) and Semichastny (a particularly arid persecutor from the Komsomol). He is imagined as the rare flower that blooms from a barren land. Moveover, Soviet propaganda itself inadvertently supports this thesis by insisting so stridently that Pasternak was never and is not now a member of the integrated Soviet community. But Pasternak himself speaks otherwise. In declining, under pressure, the Swedish prize, he gave as his reason the opprobrium attached to this honor "in the society to which I belong." This was understood abroad to have been a gesture, necessary as a minimum stratagem for survival, but meaningless. Since, however, Pasternak is a man not easily cowed and not one to resort lightly to stratagems, it is worth re-examining his claim. Is he part of the Soviet community? More particularly, has his greatness in any sense been nurtured by this community to which he claims to belong?

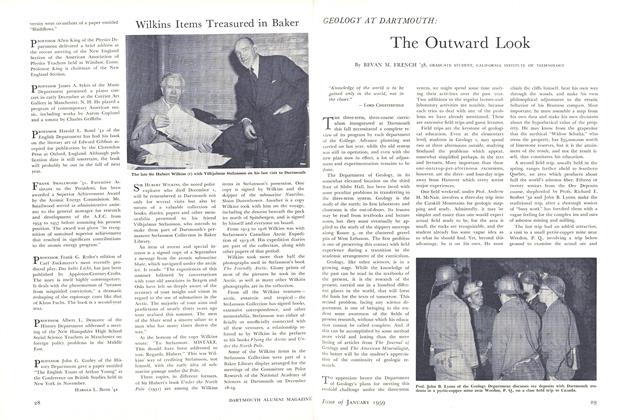

In certain specific respects Pasternak unquestionably is — or was until very recently - a member in passable standing of the Soviet literary community. For instance, his home in the dacha-village of Peredelkino, a refuge and resort for established Soviet writers, testifies to this. His income was assured through translations of Shakespeare and Georgian verse. Much of his own poetry has circulated in manuscript for years and evidently has not been without influence on younger writers (though, admittedly, the influence is not yet apparent). He has not been without companionship. Even his silence has been tolerated. All this suggests that Pasternak has been less in a state of absolute isolation than is sometimes fondly imagined.

Yet, when all is said and done, the question of his being truly a part of Russian society today remains unanswerable so long as he stands thus sharply opposed to its official spokesmen. One thing only is certain: he belongs to no other community. Some day, under happier circumstances, Doctor Zhivago will be read in Russia - where, of course, it has not yet appeared. As Edmund Wilson predicted in The New Yorker of November 15, in one of the finest reviews of the book yet to appear, the children of Pasternak's present persecutors will speak of Larisa, Zhivago and Antipov as naturally as their parents now speak of Tatiana, Onegin and Lensky, or of Natasha, Pierre and Bolkonsky.

Charles B. McLane '41, Professor of RussianCivilization at Dartmouth, joined the facultyin 1957. He was cultural with theU. S. Embassy in Moscow, 1950-52, and formerly taught at Swarthmore College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureChanging Values in College

January 1959 By PHILIP E. JACOB -

Feature

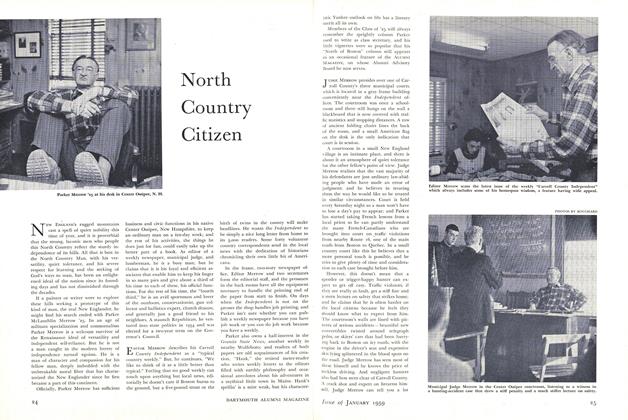

FeatureNorth Country Citizen

January 1959 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureThe Outward Look

January 1959 By BEVAN M. FRENCH '58 -

Article

Article"What Does the Tucker Foundation Do?"

January 1959 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1959 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE1 more ... -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

January 1959 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, RUSSELL J. RICE, G. KELLOGG ROSE JR.

CHARLES B. McLANE '41

-

Books

BooksTHE SOVIET DESIGN FOR A WORLD STATE.

July 1960 By CHARLES B. MCLANE '41 -

Books

BooksNO SUBSTITUTE FOR VICTORY.

DECEMBER 1962 By CHARLES B. McLANE '41 -

Books

BooksJUSTICE IN THE USSR:

MARCH 1964 By CHARLES B. MCLANE '41 -

Books

BooksSOVIET CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE: THE RSFSR CODES.

MAY 1966 By CHARLES B. MCLANE '41 -

Books

Books"A Mess of Russians"

OCTOBER, 1908 By Charles B. McLane '41 -

Books

BooksInside the Enigma

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Charles B. Mclane '41

Article

-

Article

ArticleSHERWOOD EDDY MEETINGS

May 1921 -

Article

ArticleNew Director

January 1944 -

Article

ArticleParadise in Limbo

May 1980 -

Article

ArticleFrom Dependence Upon Teaching To Independence in Learning

April 1957 By DONALD H. MORRISON -

Article

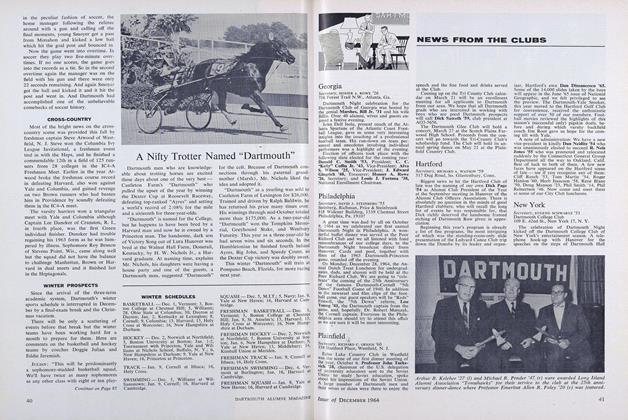

ArticleCROSS-COUNTRY

DECEMBER 1964 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleGLEE CLUB WINS ENTERTAINMENT AWARD

August 1942 By H. A. Dingwall '42