. Intro-duction and Analysis by Harold J. Berman '38; translation by Harold J. Bermanand James W. Spindler. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1966. 501 pp$11.95.

Professor Berman's translation and analysis of the recently revised Soviet criminal law codes will be welcome to serious students of Russian affairs. Their codes, published in 1960, were in preparation, ostensibly, for nearly a quarter of a century. While Stalin lived, progress on revision was understandably slow and it was only in the latter half of the 1950's that the work was completed. The new codes accordingly reflect the cautious "liberalism" of the Khrushchev era and affirm, as written, many practices long established in the West. It is entirely appropriate, of course, to question whether the force given formal law by the Soviet regime at a given juncture is what it is officially said to be. Whatever conclusion one reaches on this question, however, the codes themselves are significant for the evidence they provide of the attitudes the Soviet regime takes toward the relationship between the individual and the State in law.

In a comprehensive 139-page introduction to the codes, Professor Berman discusses their role in the Soviet legal system, the intricate history of the codes themselves, and the principal changes reflected in the present revisions. In general, and despite the extension of the death penalty to new categories of economic crimes in the last few years, greater leniency is reflected in the 1960 codes than in their predecessors: penalties are reduced for most types of crime; certain offenses, formerly considered punishable crimes, are now referred to social agencies for remedy; the criminal liability of officials, which once brought severe penalties for simple negligence, is now greatly reduced and limited to actions undertaken by those engaged in executive duties.

The most notable changes occur in the new codes on criminal procedure, the area where the protection of Soviet citizens was weakest under Stalin and where a general absence of "due process" earned the Soviet Union its reputation as a police state. Now it is asserted that justice "shall be administered only by the courts" and the codes are constructed in such a way as to give this principle force. The antiparasitic laws of 1961, it is true, negate the liberal procedural protections where petty holliganism and "parasitism" are concerned, by giving to citizen's "courts" the right to exile offenders for a period up to five years, but the new codes appear to protect citizens where serious crimes are charged - particularly in the sensitive area of crimes against the State.

Professor Berman does not attempt, he forewarns his readers, "to relate in any systematic way the development of Soviet criminal law to Soviet political, economic, and social history"; he devotes his study rather "to a closer analysis of the raw materials out of which larger interpretation must be constructed." That is to say, he intentionally avoids the fundamental question that has preoccupied students of the Soviet legal system for decades (Professor Berman himself no less than others): is it law? And do the new codes bring Soviet jurisprudence closer to that in the West? Perhaps Professor Berman is justified in skirting these larger questions, given the magnitude of the task he has undertaken and the fact that he has addressed himself to these questions in other writings (e.g., his Justice in the USSR:an Interpretation of Soviet Law, rev. ed., Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1962). His no-nonsense approach, however, and the omission of any significant reflection on the relationship of criminal law to "Soviet political, economic, and social history" renders the present volume, for all its wealth of detail and painstaking explication, a dry exercise for the average reader. The restless, sometimes controversial, but always stimulating search for the meaning of the USSR, which characterizes most of Professor Berman's writing, is absent here; in this sense, his latest book is atypical - paradoxically through his sense of professional restraint.

Professor of Government

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

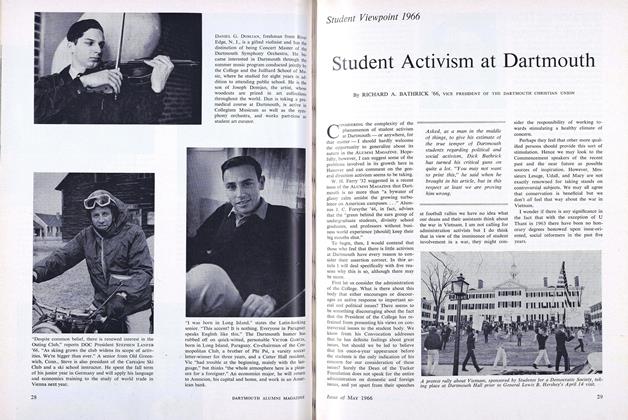

FeatureStudent Activism at Dartmouth

May 1966 By RICHARD A. BATHRICK '66 -

Feature

FeatureThe Rewards Eventually Come in the Upperclass Years

May 1966 By NELSON N. LICHTENSTEIN '66 -

Feature

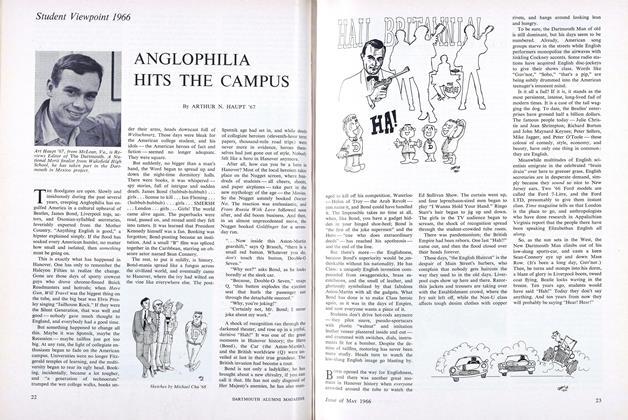

FeatureANGLOPHILIA HITS THE CAMPUS

May 1966 By ARTHUR N. HAUPT '67 -

Feature

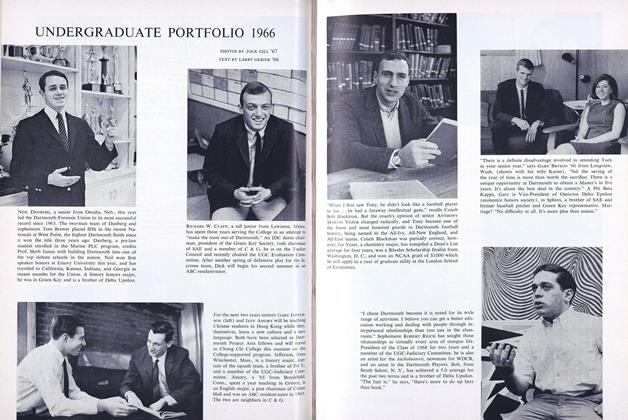

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE PORTFOLIO 1966

May 1966 By TEXT BY LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

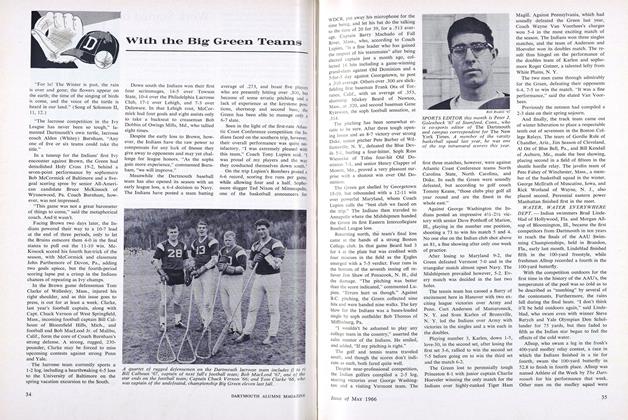

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

May 1966 -

Article

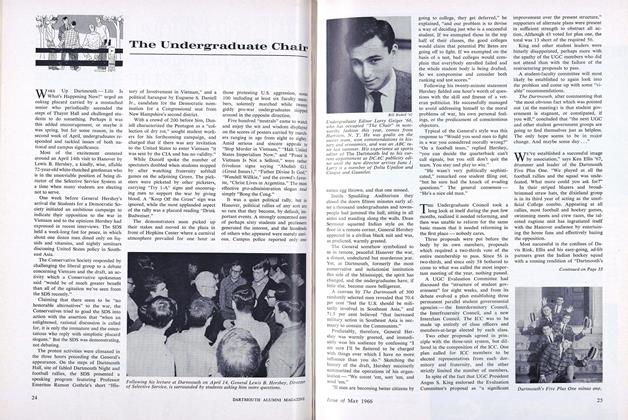

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66

CHARLES B. MCLANE '41

-

Books

BooksROOSEVELT AND THE RUSSIANS

December 1949 By Charles B. McLane '41 -

Article

ArticlePasternak and the Russian Community

JANUARY 1959 By CHARLES B. McLANE '41 -

Books

BooksNO SUBSTITUTE FOR VICTORY.

DECEMBER 1962 By CHARLES B. McLANE '41 -

Books

BooksJUSTICE IN THE USSR:

MARCH 1964 By CHARLES B. MCLANE '41 -

Books

Books"A Mess of Russians"

OCTOBER, 1908 By Charles B. McLane '41 -

Books

BooksInside the Enigma

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Charles B. Mclane '41

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

-

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN AUSTRIA WITH MUNICH AND THE BA VARIAN ALPS.

APRIL 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksPSYCHOLOGY

June 1952 By MAX SCHOEN -

Books

BooksTHE INDIAN CONSTITUTION: CORNERSTONE OF A NATION.

DECEMBER 1967 By RICHARD MORSE '44 -

Books

BooksREFLECTIONS ON THINGS AT HAND, THE NEO-CONFUCIAN ANTHOLOGY, COMPILED BY CHU HSI & LÜ-CHTEN.

NOVEMBER 1967 By T.S.K. SCOTT-CRAIG -

Books

BooksCONTEMPORARY DRAMA.

NOVEMBER 1931 By Warner Bentley