ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT

THE uneasy peace that exists today largely rests on the general fear of the power of nuclear weapons. This is peace through mutual deterrence. While it may be the best of all possible worlds, it is, nevertheless, an increasingly risky business. To be fully effective, mutual deterrence requires, first of all, that the retaliatory capability of both the United States and the Soviet Union be virtually invulnerable. A potential aggressor will then know that he will suffer drastic destruction no matter how devastating his initial attack may be. He will accordingly be deterred since there would be little advantage to his own security in striking first and grave political disadvantages in being branded an aggressor. An effective system of mutual deterrence also requires a generally stable international environment so that the major opponents can be masters of their own fate. In an unstable situation, there is always the chance that events over which the United States and the Soviet Union have no control will, through accident or miscalculation, sweep them into a thermonuclear war in which there is no commensurate interest to be gained. There would hardly seem much advantage in this happening, no matter how one calculates the relation of means to ends.

The instability of mutual deterrence suggests the need to look to disarmament as a more sensible basis for security. But here the outlook is not bright. An effective disarmament system requires either a supernational enforcement agency or a condition of complete mutual trust among the major powers. There seems little hope that either is possible. The conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union over the role of the UN Secretary General augurs ill for any agreement on an enforcement organ such as would be necessary under a general disarmament arrangement. At the same time, the history of the cold war is stark testimony to the pervasive distrust that characterizes contemporary international politics.

The coincidence of these two problems - the instability of mutual deterrence and the hopelessness of general disarmament - has driven many observers to pursue a middle road: the control of limited aspects of the arms race. The purposes of arms control programs are twofold: to stabilize the conditions of mutual deterrence and to provide a first step towards general disarmament. These programs have included proposals for protection against surprise attack, the "denuclearization" or neutralization of dangerous areas, and the cessation of nuclear testing. The latter, particularly, has been a focus of attention and proposals for a nuclear test ban have been the subject of negotiations between the major nuclear powers since October 1958. The principal motives for the United States and the Soviet Union in continuing these talks despite continual disagreement and frustration, are two: there is a political need for the major powers to respond to a world-wide yearning for some kind of breakthrough to the spiraling arms race; and there is the impending threat (already a reality in the case of France) of more nations developing a nuclear weapons capability.

The spread of nuclear weapons is bound to have an important impact on international politics. On the one hand, secondary nuclear powers might become a restraining force on the United States and the Soviet Union. But, on the other, more people will be involved with atomic weapons, more conflicts will be subjected to the tensions of an atomic threat, and more viewpoints will have to be reconciled before any agreement to limit production or use can be made. The end result is most likely to be increased instability. The timetable for controlling membership in the so-called "nuclear club" is, however, short. A recent report of the National Planning Association on "the Nth Country Problem" listed the following countries as being "able to embark on a successful nuclear weapons program in the near future: Belgium, Canada, Communist China, Czechoslovakia, West Germany, East Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Sweden, and Switzerland." The report went on to indicate that "most of these countries are highly industrialized and either have operating reactors, or have already made plans and arrangements for obtaining reactors"; and also that "a number of these countries have already talked about embarking on a nuclear weapons program."

If time is short, what are the issues that divide the United States and the Soviet Union after two and a half years of serious negotiation? Basically, these differences involve the authority to be granted to a control and inspection agency to monitor the final agreement. Inspection has, of course, been a major stumbling block in all disarmament and arms control discussions since 1946. In the case of the nuclear test ban proposals, however, the Soviet Union has accepted the principle of inspection, and agreement has already been largely gained on a control system for explosions in the air, in outer space, and underwater. Disagreement now centers on the nature of the control system for underground testing.*

Agreement on control of underground testing has been stymied by the discovery of the so-called muffling process which reduces the seismic effect of underground blasts by a factor of about 300. To this is added a second complication - that nuclear explosions cannot be distinguished from earthquakes with available seismic equipment. As a result of these two factors, a large nuclear blast might show up on instrumentation only as a common fly type of natural disturbance, of which there are many. The only precautionary measure that might be taken - given the present state of seismology - is an on-the-spot inspection of every disturbance over a very low minimum. While both sides have compromised on this point, the United States has insisted on an international control and inspection force that is larger in size and with greater authority than the Soviet Union is willing to accept.

These are the facts of the matter. There are, however extenuating circumstances. The large underground cavity within which the muffling process must take place is difficult to excavate. It is estimated, for example, that "a hole big enough to muffle a twenty-kiloton explosion would take more than two years [to excavate] and would cost about ten million dollars." At this price, the cost of breaking a treaty becomes very expensive indeed. For this reason, Dr. Hans Bethe, one of our foremost physicists and an adviser on the test ban negotiations, has posed these questions: "Does any country want to go to such an extreme as constructing the big hole in order to cheat on a test ban? Can we really assume that the Russians would go to the trouble of negotiating a test cessation treaty just in order to turn around the next day and violate it?"

Unfortunately, the answer to both questions could be either "yes" or "no." So long as a foolproof control is impossible (and there appears little chance of closing the technical gap completely), risks will be involved. These risks must then be judged in the light of the basic conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union - a conflict so intense that neither can offer concessions that will strengthen the security of the other and, by implication, weaken its own defenses. In the case of the United States, a less-than-perfect nuclear test ban would halt (and, indeed, has halted) experiments designed to develop a more diversified family of nuclear weapons without absolute assurance that similar experiments were not being carried out by the Soviet Union. This is particularly critical with regard to the development of a small-packaged nuclear warhead needed to increase the in- vulnerability of retaliatory systems. In the case of the Soviet Union, a larger inspection program than they have already agreed to would jeopardize the closed character of Soviet society which is, itself, a major element in the psychological process of deterring the United States from taking actions inimical to Soviet interests.

It is this close connection between deterrence and arms control which is important to understand. On the one hand, arms control may contribute to stability in the world arena by limiting the members of the "nuclear club." But, at the same time, it could weaken deterrent weapons systems and thus lead to increased instability in American-Soviet relations. Any decision to continue to pursue arms control in order to limit the "nuclear club" must therefore be based on the possibility of accommodation between Soviet and American interests. Otherwise the motives for continuing to negotiate rest entirely on the need to respond to world opinion, a motive which will surely become exposed as misleading unless it is supported by a more substantial national purpose.

There is, unfortunately, controversy and confusion on how to evaluate the Soviet position on arms control and thus to assess the possibility of accommodation. The very nature of the Soviet system, "the mystery wrapped in an enigma," discourages the search for the kind of information which careful analysis requires. In sum, there are three ways of interpreting and trying to predict Soviet behavior in world politics. All three interpretations involve the interplay of certain forces in the formulation of Soviet policy: Communist ideology, the national interest of the Soviet Union, and the impact of external pressures on Soviet foreign policy. The problem constantly remains of deciding what weight to give to what forces under given conditions.

The first view of Soviet behavior emphasizes the influence of ideology. The proponents of this view insist that the ultimate aim of the Soviet Union is the destruction of western civilization, that temporary lapses of aggressiveness are but camouflage, and that conflict between the United States and Russia is constant and inevitable. They do not necessarily insist that open warfare, including thermonuclear war, must break out. But they do advocate taking a "hard line," never dropping our guard, and being prepared to meet the Soviet challenge head-on. Any tendency to avoid confrontation, to seek compromise solutions, or to assume that a mutuality of interests might be possible on any basis, is deemed to be appeasement. For those who hold this view, the only purpose of negotiations on arms control or disarmament is to feed the propaganda mills. Realistically, no agreement is possible.

The second view of Soviet behavior emphasizes the national interest of Russia. While not ignoring the importance of ideology, greater emphasis is placed on the interest of the Soviet Union as a nation than as the leader of an ideological movement. In line with this assumption, it is reasoned that it is possible for the West to live with the Soviet Union. The aggressiveness of the Russians is largely attributed to the threats to their national security that have come from the continual hostility of the West. In the face of this hostility, Soviet leaders have had to be realistic and refuse to agree to arms control proposals that would place them in a constant minority without an absolute veto. They have thus been forced to pursue an armament policy to protect themselves. They no longer have the ideological imperative to expand their control until they are masters of the world. If their essential interests as a nation can be satisfied and not constantly threatened by a hostile West, then we can expect that agreements with the Soviet Union will be observed in accordance with the basic principle of international law, pactasunt servanda (treaties are binding).

Politics is a complex business. Both these views of Soviet behavior bear a core of truth that is impossible to deny. It is impossible to ignore the importance of ideology in every move the Soviet Union makes. Indeed, even if we wanted to ignore it, it is doubtful that Khrushchev would let us. Everything that the Soviet Union does is justified by Soviet leaders in ideological terms. Whether or not this is simply rationalization is almost irrelevant. The propensity to rationalize suggests that the ideology has an inner dynamism of its own which may or may not be coincident with the national interest of the Soviet Union. This, in fact, leaves us with a tremendously risky situation. There is the ever-present danger that the compulsion for ideological justification, if not the motivation of ideological objectives, could drive Soviet leaders farther than would be the case if the national interest were the determining element in their behavior.

Nevertheless, the Soviet Union is forced to operate within the framework of an international system in which national interest is a dominant feature. It is being challenged by rising national systems within the communist bloc itself - the heresy of Tito's Yugoslavia, the middle road of Gomulka's Poland, and the long-range threat of Mao Tse-tung's China. The strength of the Soviet position within the communist bloc is thus as dependent on the exercise of national power as it is on ideological leadership. Moreover, the Soviet Union is confronted with the new nationalism of the developing states in those areas of the world - Asia, Africa, and Latin America - where the focus of the cold war has now shifted. At the risk of alienation, it must thus be responsive to the growing determination of these states to avoid alignment and to use their influence to shape an international environment in which their own development can be hastened. Finally, there is the desire of their own people that the new economic and technological resources of the Soviet Union be trained on many of their own needs. In the face of these varied pressures, Soviet leaders must surely be cautious about taking any risks that would tend to weaken the national base of Soviet power.

The complex character of Soviet policy-making is emphasized by two recent trends. The first is the increasing questioning in the communist world about the inevitability of war between communism and capitalism. This seems to be a basic factor of disagreement between the Soviet leaders and the Chinese. One explanation lies not in a change in ideological position, but in the power position of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union has become increasingly strong since 1953 and increasingly confident of its own ability to deter the Western powers from taking military action. If the reason why war is inevitable is that capitalist classes must resort to force to pursue their aims, then it is not necessarily inevitable if the Soviet Union can exert such pressures that the capitalistic bloc will be reluctant to risk their own survival by using armed power.

This first trend is related to a second - an increasing discussion in Soviet circles of the impact of thermonuclear war on all participants. One of the clearest statements on this is in an article by Major General N. Talenski, an influential military strategist in the Soviet Union. Writing in the fall of 1960, Talenski said: "The process of development of the technique for destroying people has led to such a situation that it is impossible to use weapons for deciding political questions as used to be for thousands of years. Nuclear rocket war is extremely dangerous, not only for the side which is attacked, but is suicidal for the aggressor himself."

Analyzed against the complex nature of Soviet policy-making, these trends suggest that, in Soviet strategy, there is a level of violence beyond which the use of force as an instrument of policy is no longer rational. At the same time, there is no doubt that the Soviet Union is at conflict with the West. It must therefore seek a position from which to control this conflict below the level of violence of thermonuclear war and to control any situation that could by chain-reaction lead to thermonuclear war. Both these objectives must, moreover, be achieved without disturbing the deterrent capability that the Soviet Union now has vis-a-vis the Western powers. Not only must the Soviet leaders be able to convince the West of this, but they must also convince the communist bloc of the continued pre-eminence of the Soviet Union.

This is the real test that an arms control agreement must pass if it is going to gain Soviet approval: to permit the Soviet Union to increase its control over the level of violence that might be employed in international politics and its control over situations which could lead to the use of violence beyond this level. Ultimately there is no one set of conditions under which these objectives might be gained. Soviet policymakers have to make choices and weigh feasible alternatives in much the same way our own leaders do. They may be surer of their objectives and less subject to the pressures of open discussion, but they must still face the necessity of choice.

The big question for the United States is whether arms control under these conditions is advantageous. If we begin with the premise that anything that seems to be desirable to the Soviets will be detrimental to American interests, then obviously it is not. But if we accept the fact that the Soviets are not going to agree to any control system that they do not consider is to their advantage, then there would seem to be a basis to continue negotiations if we can also accept these same objectives as legitimate aims of the United States.

The paradoxical truth is that both the Soviet Union and the United States have a certain stake in the status quo with regard to the distribution of nuclear weapons. This does not eliminate the need to vie for tactical advantages in the bargaining process that might lead to an arms control system - but it does offer a basis for agreement if both nations recognize it as such. There are, nevertheless, risks in assuming that the Soviet Union is proceeding in this same light. But these risks need to be viewed against the dynamic character of history and against the dilemma of seeking to achieve these same objectives when the capability to produce nuclear weapons has spread to the "Nth country."

It is difficult to imagine a more perplexing set of problems than those that face us in the field of national security. At each step we face a crisis of choice and of conscience. There are no refuges. We cannot assume that a technological break-through will bring us a foolproof control system - or that time and the turn of events will, by themselves, bring us closer to a solution - or that the Soviet leaders will one day respond, without question and counterproposal, to our own sense of reason and right. There is no alternative to an intelligent choice of policy and a vigorous defense of position. Nor, might I add, will there ever be.

* The situation described here is that prevailing as of April 1 1961. Negotiations are, however, continuing on a test cessation agreement and the two sides may be closer or farther from an accord by the time this is printed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Human Revolution and World Peace

May 1961 By RICHARD W. STERLING, -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Defense on the Economy

May 1961 By GEORGE E. LENT, PROFESSOR -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Teaching

May 1961 By FRANKLIN SMALLWOOD '51, -

Feature

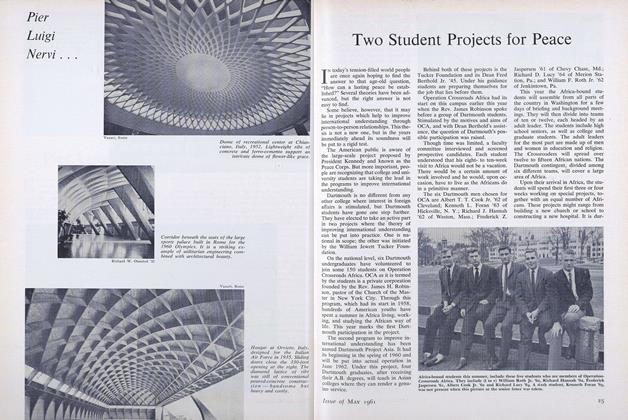

FeatureTwo Student Projects for Peace

May 1961 By D.E.O. -

Feature

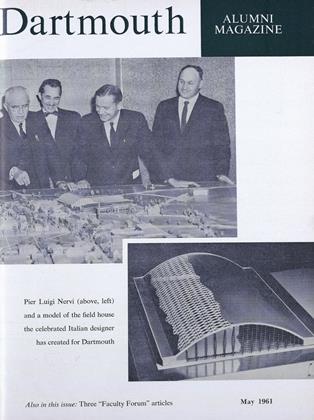

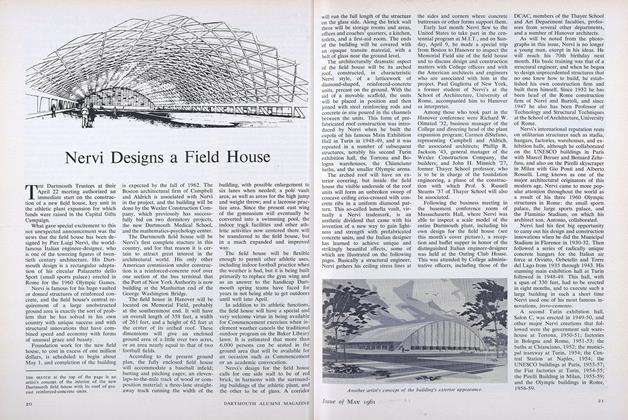

FeatureNervi Designs a Field House

May 1961 -

Feature

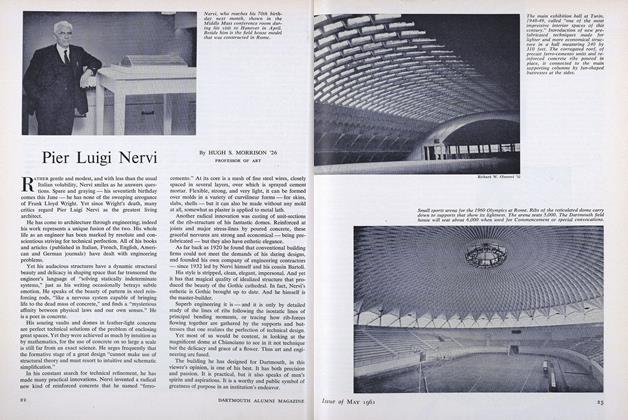

FeaturePier Luigi Nervi

May 1961 By HUGH S. MORRISON '26

Features

-

Cover Story

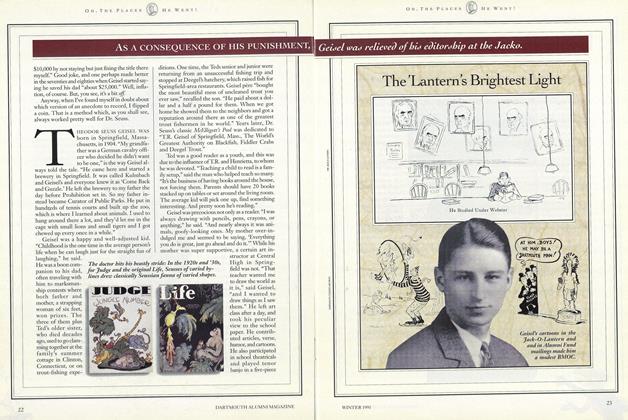

Cover StoryThe 'Lanterns' Brightest Light

December 1991 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Mar/Apr 2013 By Joanna Kidd ’99, Joanna Kidd ’99 -

Feature

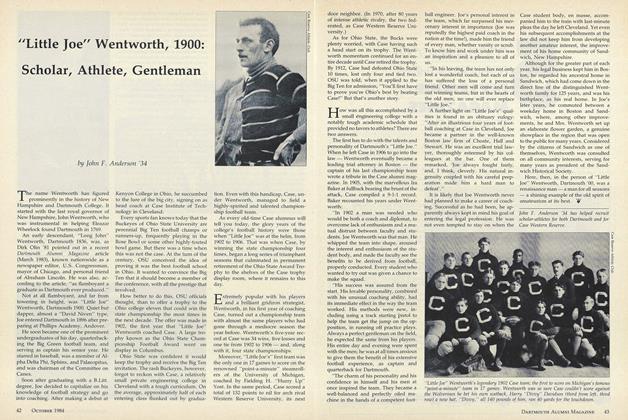

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

OCTOBER 1984 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

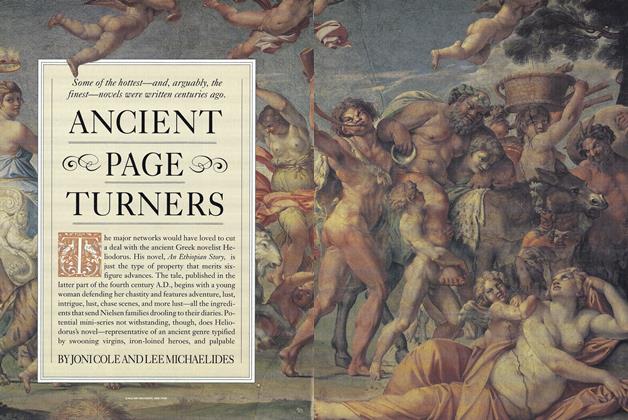

FeatureANCIENT PAGE TURNERS

MARCH 1990 By JONI COLE AND LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Mar/Apr 2006 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureThe River

APRIL 1992 By W. D. Wetherell