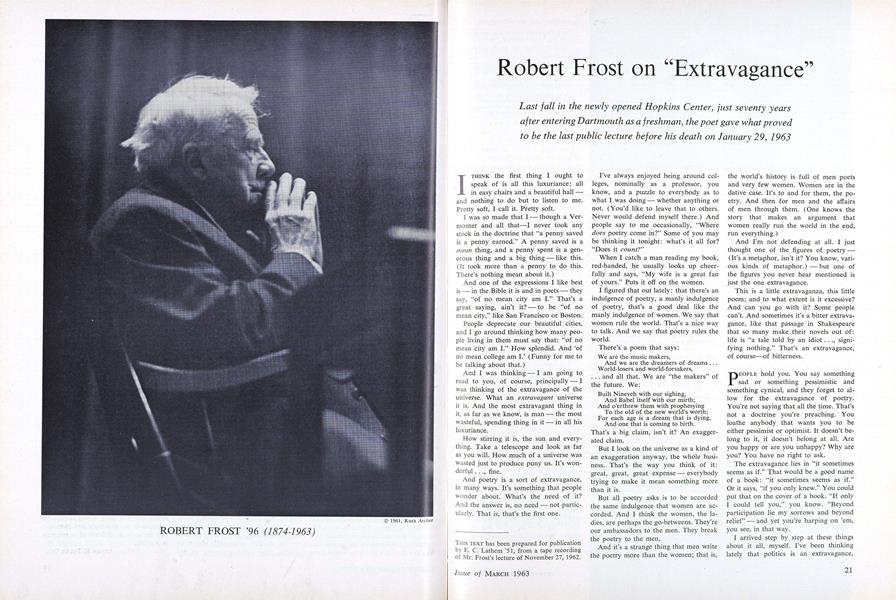

Last fall in the newly opened Hopkins Center, just seventy yearsafter entering Dartmouth as a freshman, the poet gave what provedto be the last public lecture before his death on January 29, 1963

I THINK the first thing I ought to speak of is all this luxuriance: all in easy chairs and a beautiful hall - and nothing to do but to listen to me. Pretty soft, I call it. Pretty soft.

I was so made that I — though a Vermonter and all that — I never took any stock in the doctrine that "a penny saved is a penny earned." A penny saved is a mean thing, and a penny spent is a generous thing and a big thing - like this. (It took more than a penny to do this. There's nothing mean about it.)

And one of the expressions I like best is - in the Bible it is and in poets - they say, "of no mean city am I." That's a great saying, ain't it? - to be "of no mean city," like San Francisco or Boston.

People deprecate our beautiful cities, and I go around thinking how many people living in them must say that: "of no mean city am I." How splendid. And 'of no mean college am I.' (Funny for me to be talking about that.)

And I was thinking - I am going to read to you, of course, principally - I was thinking of the extravagance of the universe. What an extravagant universe it is. And the most extravagant thing in it, as far as we know, is man - the most wasteful, spending thing in it - in all his luxuriance.

How stirring it is, the sun and everything. Take a telescope and look as far as you will. How much of a universe was wasted just to produce puny us. It's wonderful . . .,fine.

And poetry is a sort of extravagance, in many ways. It's something that people wonder about. What's the need of it? And the answer is, no need - not particularly. That is, that's the first one.

I've always enjoyed being around colleges, nominally as a professor, you know, and a puzzle to everybody as to what I was doing - whether anything or not. (You'd like to leave that to others. Never would defend myself there.) And people say to me occasionally, "Where does poetry come in?" Some of you may be thinking it tonight: what's it all for? "Does it count?"

When I catch a man reading my book, red-handed, he usually looks up cheerfully and says, "My wife is a great fan of yours." Puts it off on the women.

I figured that out lately: that there's an indulgence of poetry, a manly indulgence of poetry, that's a good deal like the manly indulgence of women. We say that women rule the world. That's a nice way to talk. And we say that poetry rules the world.

There's a poem that says:

We are the music makers, And we are the dreamers of dreams . . . World-losers and world-forsakers, . . . and all that. We are "the makers" of the future. We:

Built Nineveh with our sighing, And Babel itself with our mirth; And o'erthrew them with prophesying To the old of the new world's worth; For each age is a dream that is dying, And one that is coming to birth.

That's a big claim, isn't it? An exagger- ated claim.

But I look on the universe as a kind of an exaggeration anyway, the whole busi- ness. That's the way you think of it: great, great, great expense - everybody trying to make it mean something more than it is.

But all poetry asks is to be accorded the same indulgence that women are accorded. And I think the women, the ladies, are perhaps the go-betweens. They're our ambassadors to the men. They break the poetry to the men.

And it's a strange thing that men write the poetry more than the women; that is, the world's history is full of men poets and very few women. Women are in the dative case. It's to and for them, the poetry. And then for men and the affairs of men through them. (One knows the story that makes an argument that women really run the world in the end, run everything.)

And I'm not defending at all. I just thought one of the figures of poetry (It's a metaphor, isn't it? You know, various kinds of metaphor.) — but one of the figures you never hear mentioned is just the one extravagance.

This is a little extravaganza, this little poem; and to what extent is it excessive? And can you go with it? Some people can't. And sometimes it's a bitter extravagance, like that passage in Shakespeare that so many make their novels out of: life is "a tale told by an idiot. . signifying nothing." That's an extravagance, of course—of bitterness.

PEOPLE hold you. You say something sad or something pessimistic and something cynical, and they forget to allow for the extravagance of poetry. You're not saying that all the time. That's not a doctrine you're preaching.' You loathe anybody that wants you to be either pessimist or optimist. It doesn't belong to it, it doesn't belong at all. Are you happy or are you unhappy? Why are you? You have no right to ask.

The extravagance lies in "it sometimes seems as if." That would be a good name of a book: "it sometimes seems as if." Or it says, "if you only knew." You could put that on the cover of a book. "If only I could tell you," you know. "Beyond participation lie my sorrows and beyond relief" - and yet you're harping on 'em, you see, in that way.

I arrived step by step at these things about it all, myself. I've been thinking lately that politics is an extravagance, again, an extravagance about grievances. And poetry is an extravagance about grief. And grievances are something that can be remedied, and griefs are irremediable. And there you take 'em with a sort of a happy sadness, that they say drink helps - say it does. ("Make you happy .. . the college song goes, "Make you happy, make you sad. . . That old thing. How deep those things go.)

That leads me to say an extr[avagance], I think I have right here one. Let's see it. (It's made out in larger print for me by my publishers.) I remember somebody holding it up for some doctrine that's supposed to be in it. It begins with this kind of a person:

He thought he kept the universe alone; . . . Just that one line could be a whole poem, you know:

He thought he kept the universe alone; For all the voice in answer he could wake Was but the mocking echo of his own From some tree-hidden cliff across the lake.

Some morning from the boulder-broken beach He would cry out on life, that what it wants Is not its own love back in copy speech, But counter-love, original response.

And nothing ever came of what he cried Unless it was the embodiment that crashed In the cliff's talus on the other side, And then in the far distant water splashed, But after a time allowed for it to swim, Instead of proving human when it neared And someone else additional to him, As a great buck it powerfully appeared, Pushing the crumpled water up ahead, And landed pouring like a waterfall, And stumbled through the rocks with horny tread, And forced the underbrush - and that was all.

That's all he got out of his longing.

And somebody made quite an attack on that as not satisfying the noblest in our nature or something, you know. He missed it all! [. . .]

But that's just by way of carrying it over from what I was talking. I usually, you know, talk without any reference to my own poems: talk politics or something.

And then, just thinking of extravagances, back through the years, this is one - with a title like this, "Never Again Would Birds' Song Be the Same." You see this is another tone of extravagance:

He would declare and could himself believe .. . This is beginning to be an extravagance right in that line, isn't it?:

He would declare and could himself believe That the birds there in all the garden round From having heard the daylong voice of Eve Had added to their own an oversound, Her tone of meaning though without the words.

Admittedly an eloquence so soft Could only have had an influence on birds When call or laughter carried it aloft.

Be that as may be, she was in their song.

Moreover her voice upon their voices crossed Had now persisted in the woods so long That probably it never would be lost.

Never again would birds' song be the same.

And to do that to birds was why she came.

(They used to write extravagant things to ladies' eyebrows, you know. That's one of the parts of poetry.)

Some people are incapable of taking it, that's all. And I'm not picking you out. I do this on a percentage basis! And I can tell by expression of faces how troubled they are, just about that. I think it's the extravagance of it that's bothering 'em.

Say in a Mother Goose thing like this -another kind of extravagance:

There was a man and he had nought, So the robbers came to rob him; . .. naturally. You see, that's an extravagance there:

There was a man and he had nought, So the robbers came to rob him; He climbed up to his chimney-top. And then they thought they had him.

But he climbed down on t'other side, And so they couldn't find him; He ran fourteen miles in fifteen days, And never looked behind him.

Now, that's all; if you can't keep up with it, don't try to!

AND then, I could go right on with L pretty near everything I've done. There's always this element of extravagance. It's like snapping the whip: Are you there? Are you still on? Are you with it? Or has it snapped you off?

That's a very emotional one, and then this is one in thought - a recent one, another kind of tone altogether:

There was never naught, There was always thought.

But when noticed first It was fairly burst Into having weight.

It was in a state Of atomic One.

Matter was begun - And in fact complete. One and yet discrete To conflict and pair.

Everything was there Every single thing Waiting was to bring, Clear from hydrogen All the way to men.

It was all the tree It would ever be, Bole and branch and root Cunningly minute.

And this gist of all Is so infra-small As to blind our eyes To its every guise And so render nil The whole Yggdrasil.

Out of coming-in Into having been!

So the picture's caught Almost next to naught But the force of thought.

And my extravagance would go on from there to say that people think that life is a result of certain atoms coming together, instead of being the cause that brings the atoms together. There's something to be said about that in the utter, utter extravagant way.

And then ...., another one. This is a poem that I partly wrote while I was here at Dartmouth in 1892, and failed with. And I kept a couple of lines of it, and they came in later. You can see what I was dwelling on. I was dwelling on the Pacific Coast - the shore out at Cliff House, where I had been as a child:

The shattered water made a misty din.

Great waves looked over others coming in,

And thought of doing something to the shore That water never did to land before.

The clouds were low and hairy in the skies, Like locks blown forward in the gleam of eyes.

You could not tell, and yet it looked as if The shore was lucky in being backed by cliff, The cliff in being backed by continent; It looked as if a night of dark intent Was coming, and not only a night, an age.

Someone had better be prepared for rage.

There would be more than ocean-water broken Before God's last Put out the Light was spoken.

Another one, you see, just the way it all is. (Some of them probably more than others.)

And then sometimes just fooling, you know:

I once had a cow that jumped over the moon, ... This poem is called "Lines Written in Dejection on the Eve of Great Success":

I once had a cow that jumped over the moon, Not on to the moon but over.

I don't know what made her so lunar a loon; All she'd been having was clover.

That was back in the days of my godmother Goose.

But though we are goosier now, And all tanked up with mineral juice, We haven't caught up with my cow.

Same thing, you know.

And one of the things about it in the criticism, and where I fail, is in I can enjoy great extravagance — and abandon. Abandon, especially when it's humorous. (I can show you other things, too; they're not all humorous.) ... I can enjoy it. But some of this solemn abandon - (I don't know what it is they call 'em, abstract art or something like that.)— I don't keep up with it. You see, I'm distressed a little. ... You get left behind, at some age. Don't sympathize with me too much!

And then, take a thing like this:

But God's own descent Into flesh was meant As a demonstration That the supreme merit Lay in risking spirit In substantiation.

That's a whole of philosophy. To the very limit, you know.

And it comes out. ... It doesn't mean it's untruth, this extravagance. For instance, somebody says to me - a great friend - says, "Everything's in the Old Testament that you find in the New." (You can tell who he was probably by his saying that.)

And I said, "What is the height of it?"

"Well," he said, " 'love your neighbor as yourself.' "

I said, "Yeah, that's in both of them." Then, just to tease him, I said, "But it isn't good enough."

He said, "What's the matter with it?"

"And hate your neighbor as you hate yourself."

He said, "Do you hate yourself?"

"I wouldn't be religious unless I did."

You see, we had in an argument - of that kind....

SOME people can't go with you. Let 'em drop; let 'em fall off. Let the wolves take 'em.

In the Bible twice it says - and I quote that in a poem somewhere, I think; yes - twice it says, 'these things are said in parables . . .' - said in this way that I'm talking to you about: extravagance said in parable, '. . . so the wrong people won't understand them and so get saved.'

It's thoroughly undemocratic, very superior - as when Matthew Arnold says, in a whole sonnet, only those who've given everything and strained every nerve "mount, and that hardly, to eternal life." 'Taint everybody, it's just those only - the few that have done everything, sacrificed, risked everything, "bet their sweet life" on what they lived. (That's again. . . . What a broad one that is: "You bet your sweet life." That's the height of it all, in whatever you do: "bet your sweet life.") And only those who have done that to the limit, he says, "mount, and that hardly..." - they barely make it, you know —"... that hardly, to eternal life."

I like to see you. I like to bother some of you. What do we go round with poetry for? Go round just for kindred spirits some way - not for criticism, not for appreciation, and nothing but just awareness of each other about it all.

Now I'm going to forget all that, but let me say an extravagance of somebody else, another one beside mine. See how rich this is - not mine at all:

By feathers green, across Casbeen The traveller tracks the Phoenix flown, By gems he strew'd in waste and wood, And jewell'd plumes at random thrown.

Till wandering far, by moon and star, They stand beside the funeral pyre, Where bursting bright with sanguine light The impulsive bird forgets his sire.

Those ashes shine like ruby wine, Like bag of Tyrian murex spilt, The claws, the jowl of the flying fowl Are with the glorious anguish gilt.

So fair the sight, so bright the light, Those pilgrim men, on traffic bent, Drop hands and eyes and merchandise, And are with gazing well content.

That's somebody else, but that's another example - a rich one, lush, lavish.

Then, another kind of thing — not all my own, you know. Take for just the delight in the sound of the two stanzas that I'll say to you — three stanzas, maybe. The way it changes tune with a passion — a religious passion, I guess you'd call it. This is an old poem — old, old poem. It says:

What if the king, our sovereign lord, Should of his own accord Friendly himself invite, And say 'I'll be your guest tomorrow night,' How should we stir ourselves, call and command All hands to work! Let no man idle stand!'

'Set me fine Spanish tables in the hall; See they be fitted all; . . . then I skip a little, and it says:

Thus, if a king were coming, would we do; And 'twere good reason too; For 'tis a duteous thing To do all honor to an earthly king, And after all our travail and our cost, So he be pleased, to count no labor lost.

. . . and then watch this, the extravagance of this:

But at the coming of the King of Heaven . . . see, we've talked about the coming of the earthly king:

But at the coming of the King of Heaven All's set at six and seven; We wallow in our sin, Christ cannot find a chamber in the inn. We entertain Him always as a stranger, And, as of old, still house Him in the manger.

That's just letting go - saying. Then, another strange one. You could say this is bad, you know; it lets you down too much. (That doesn't; that's great stuff; that lifts you up.) But suppose someone says:

In either mood, to bless or curse God bringeth forth the soul of man; No angel sire, no mother nurse Can change the work that God began.

One spirit shall be like a star, He shall delight to honor one:

Another spirit he shall mar:

None may undo what God hath done.

Then go back to just in general... . I'll just say 'em, I guess - little ones now. Some old ones I'll mix with some new ones.

The first poem I ever read in public, in 1915, was at Tufts College, and this was it - 1915:

[Mr. Frost said "The Road Not Taken."]

Then - that's an old one — then an- other old one, quite a different tone. This one is more casual talking, this next one:

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though; He will not see me stopping here To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near Between the woods and frozen lake The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound's the sweep Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep, But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep.

AND that. .. .'I won't use the word extravagance again this evening. Swear off. (You know sometimes a talk is just trying to run away from one word. If you get started using it you can't get away from it, sometimes.)

But then a new one. (That's supposed to be a problem poem. I didn't write it for that, but it's supposed to be a problem poem. By analogy you can go off from anything. Someone says that means - "The woods are lovely, dark and deep, /But I have promises to keep" - that means the world is "lovely. ..," life is "lovely, dark and deep," but I must be getting to heaven. You see it's a death poem. You don't mind that. You shouldn't. Let 'em go!) And then here's a new one. "Away!" this is called, "Away!" Little stanzas, tiny stanzas:

Now I out walking The world desert, And my shoe and my stocking Do me no hurt.

I leave behind Good friends in town.

Let them get well-wined And go lie down.

Don't think I leave For the outer dark Like Adam and Eve Put out of the Park.

Forget the myth.

There is no one I Am put out with Or put out by.

Unless I'm wrong I but obey The urge of a song:

I'm—bound—away!

And I may return If dissatisfied With what I learn From having died.

That's straight goods. They can't do much with that.

And then - just as it happens now; it's nothing to do with anything particular - "Escapist - Never." (These are some of my new ones.):

[Mr. Frost said "Escapist - Never," "Closed for Good," "Peril of Hope," "The Draft Horse," and "One More Brevity."]

I would like to read part of something to you that's hard to read. It's in my new book, and I have it here in large print for my eye. . . .

This is in blank verse. You know me well enough to know I've written in nothing but blank verse and rhymed verse. I did write one free verse poem, and I kept it. I thought it was so smart!

A lady said to me one night, "You've said all sorts of things tonight, Mr. Frost. Which are you, a conservative or a radical?"

And I looked at her very honestly and earnestly and sincerely, and I said:

I never dared be radical when young For fear it would make me conservative when old.

That's my only free verse poem.

This is in blank verse, and the title of it (and the little reading of it's all you're going to get): "How Hard It Is to Keep from Being King When It's in You and in the Situation." It's kind of, in a way, political and invidious—but you wouldn't know who I was driving at, maybe - maybe you would. But it's an old story:

[Mr. Frost read approximately half of the poem.]

. . . And that's where I'll leave it. There's twice as much of it. See the rest of it, how it comes out: how the cook becomes king and the other man wants himself executed, the regular king.

AND I guess I've taken my time with you - or let me say one or two little things.

So many of them have literary criticism in them —in them. And yet I wouldn't admit it. I try to hide it.

So many of them have politics in them, like that - that's just loaded with politics. I got it out of the Arabian Nights, of course, the outline of the story; but it's just loaded, loaded with politics. And I've bent it to make it more so, you see. I'm' guilty. And al! that.

But now this one, speaking to a star up there:

[Mr. Frost said "Choose Something Like a Star."]

By that star I mean the Arabian Nights or Catullus or something in the Bible or something way off or something way off in the woods, and when I've made a mistake in my vote. (We were talking about that today. How many times we voted this way and that by mistake.)

And then see little personal things like this. ... (Do you know the real motivation probably of it all. . . ? Take the one line in that, "Some mystery becomes the proud." Do you know where I got that? Out of long efforts to understand contemporary poets. You see, let them be mystery. And that's my generosity - call it that! If I was sure they meant anything to themselves it would be all right.)

Now take a little one like this - you see how different my feeling's about it:

She always had to burn a light Beside her attic bed at night.

It gave bad dreams and troubled sleep, But helped the Lord her soul to keep.

Good gloom on her was thrown away.

It is on me by night or day, Who have, as I foresee, ahead The darkest of it still to dread.

Suppose I end on that dark note.

Good night.

ROBERT FROST '96 (1874-1963)

Taken at Franconia, N.H., where he bought a farm upon his return from Englandin 1915, this photograph shows Robert Frost at about the time he gave his first lecture and poetry reading at Dartmouth in January 1916.

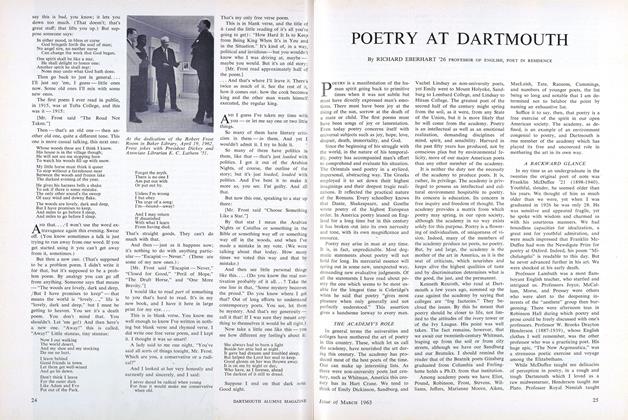

Frost, who was Ticknor Fellow in the Humanities at Dartmouth from 1943 to 1949,shown in his Baker Library study with some of the Navy V-12 trainees of 1943-44.

At the dedication of the Robert FrostRoom in Baker Library, April 19, 1962,Frost jokes with President Dickey andAssociate Librarian E. C. Lathem '51.

THIS TEXT has been prepared for publication by E. C. Lathem '51, from a tape recording of Mr. Frost's lecture of November 27, 1962.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePOETRY AT DARTMOUTH

March 1963 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Feature

FeatureTHE SECRET LIFE OF RICHARD WATT

March 1963 By DON MURRAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1963 By JOHN HURD, HUGH M. MCKAY -

Article

ArticleScholarly Stimulator of Comparative Study

March 1963 By G.O'C. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1963 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, ALBERT W. FREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

March 1963 By ROBERT W. MACMILLEN, DONALD G. RAINIE

Features

-

Feature

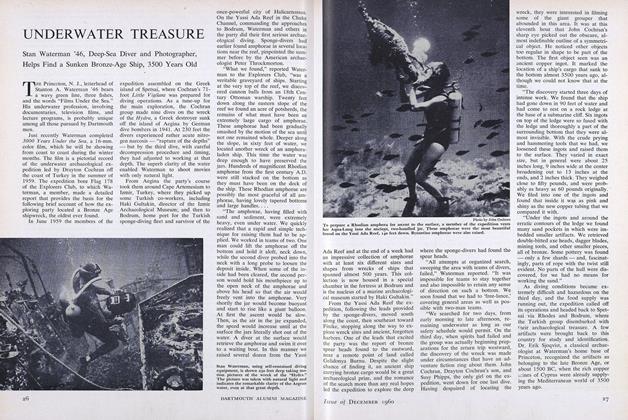

FeatureUNDERWATER TREASURE

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureScholarship Aid at Record Level

JANUARY 1969 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThorne Smith 1914

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

Feature...AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

March 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO NAIL A PERFECT FIELD GOAL

Jan/Feb 2009 By NICK LOWERY '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth Dogs

OCTOBER 1997 By Robert Nutt '49