A TRI-MONTHLY SUPPLEMENT TO THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTINUING THE EDUCATIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACULTY AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGE

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT

REVOLUTIONARY" and "explosive" are terms aptly used today to describe the physical sciences and the technology they have produced. These terms are particularly appropriate - and depressing - when applied to the realm of nuclear weaponry. They symbolize the urgent need for continuing and expanding efforts to control the development and use of armaments.

Yet the use of these terms will mislead us unless we recognize that they are equally applicable to the social and political life of humanity. We must not be hypnotized by the awesome facts of nuclear science. We must realize that revolutionary changes and explosive demands are the hallmarks of all life in today's world. Armaments are only one of the threats to peace. In order to explore prospects for a better fate than nuclear annihilation, we must look beyond the arsenals. We must understand and then deal successfully with the human revolutions that characterize our world. Only if we do this can we hope to prevent the threat of nuclear destruction from becoming a reality.

We see revolutionary, explosive changes in almost every direction. I propose to discuss here just a few of the factors behind these changes. Then, rather than simply putting them on display for the reader's inspection, I shall run the risk of suggesting some possible ways to deal with these factors.

The first and most obvious explosive factor is the human being himself - he is multiplying at an incredibly accelerated rate. It took tens of centuries to bring world population to the billion mark - it took one century to add a second billion. It will take about 35 years to add the third billion from 1930 to 1965. But then, according to best estimates, another 35 years will suffice to double the whole three billion - and more - so that by the year 2000 we will have a global population of between six and seven billion.

Some scientists say that it is physically possible to nourish and clothe this vast hive of people. But our real question is: is it politically possible? For the really explosive growth in population is taking place in the areas least capable of absorbing it - in the countries where economic growth is right now falling behind the birth rate. In the most prosperous parts of the world, the United States and Canada, Europe, and the Soviet Union, total population is estimated to rise from 836 million in 1960 to 1,259 million in the year 2000 - roughly a 50% increase. But in the least prosperous regions of the world - Asia, Africa, Latin America the anticipated increase is 150%: from 1 billion 966 million today to 4 billion 826 million in 2000.

We are outnumbered. The wealthy and reasonably well-off are today outnumbered by the poor and the desperate 2 to 1. If we don't make major efforts to help keep population lower and raise living standards where they are at their worst, the ratio will shift from 2 to 1 to 4 to 1. Many will remember those ominous days in America when Franklin D. Roosevelt could say with truth that one-third of the nation was ill-fed, ill-clothed and ill-housed. When he said those words this country was not so far from revolution. If we ever come to the stage where we must say that four-fifths of the world is ill-clothed, ill-housed, and ill-fed, we will not be simply in danger of violent revolution; we will already be fighting, with nuclear weapons or with rocks.

The world has long tolerated vast differences between rich and poor. But this tolerance has now run its course, and this is the second revolutionary factor in our catalog. These masses of new human beings are entertaining revolutionary expectations of personal liberty and of enough material goods to make that liberty meaningful and dignified. Our past, our present deeds, our conscience, and our interest spur us to whet and increase these appetites for liberty and economic welfare among those who have until now had to go hungry. Our past - one of direct or indirect imperialism - bound the old colonial areas to the West and set Western standards before them as the most desirable goals to which to aspire. Our present - the continuing productivity in new and more rapid means of communication, makes at least the economic and technological achievements of the West ever closer and more tangible to the poorest society. These same means of communication have, in turn, brought the poor of the world to our consciousness as never before. Our conscience, even though often only sporadically, has urged us on to offer the world's poor both help and hope. Our interest pushes us inexorably in the same direction. The Soviets are providing us with formidable competition which goads us on when both conscience and comprehension begin to falter.

There is no prospect whatsoever that the demands and expectations of the world's poor will let up or become less pressing. On the contrary, they will grow louder and more insistent. The tragedy, and the third revolutionary factor we must consider, is that there is now no adequate political, technical, or administrative machinery to fulfill these demands. The revolutionary shouts for change and a better life - whether in Cuba, the Congo, or Indonesia - are not directed at the local governments there, but at the world. There are not enough machines, food, banks or factories in these lands to supply the needs. There are not enough skilled people to identify and minister to the needs. The have-not countries are have-nots in every sense. They lack not only material goods but the institutions which could aid in the fair and rational distribution of what material goods are available. On almost every hand we are faced with immature, unstable, and unrepresentative governments which by definition cannot satisfy the desires of their people. One need only cite the well-known figure of seventeen native university graduates in all of the Congo as a symbolic warning and reminder. The only way the revolutionary demands can begin to be met is by drawing on the countries which have an abundance of material wealth and which have the facilities to teach the skills necessary to distribute wealth and to create new wealth.

But - and here is a fourth revolutionary factor - when we are dealing with the underdeveloped world we are dealing now not with colonies but with sovereignties. We cannot look at the necessary economic aid and skill-creating programs as simply a one-way transmission belt by which a metropolitan center builds up its colonial hinterland. The new countries are determined to be nobody's back yard. They are extremely sensitive to the inevitable links between economic aid and political influence. Since these links cannot be effectively broken, there is a natural tendency for the underdeveloped lands to negotiate for aid from both the West and the Soviet bloc, in order to maintain a balance of influence - another version of the familiar balance of power.

Another new and revolutionary factor: these newcomers to independence can wield enormous influence themselves, far beyond what newcomers could exercise in the international society of the past. This is due to the forum to which all now have access - the United Nations. And it is also due to the sheer multitude of new states. They now exist in such numbers that they virtually dominate the General Assembly. The old League of Nations was pretty exclusively an affair of long-established European and Latin American nations. The United Nations began its life largely repeating the League of Nations pattern. But today the new nations of Asia and Africa constitute almost half of the entire UN membership. Soviet and American policy in the UN both have to allow for the ideals, prejudices and animuses of the most powerful voting group in the General Assembly.

There are many other explosive factors: the deep-running issues which directly divide East and West such as Berlin, China, Korea, armaments. There is a revival of the older nationalisms. We see this particularly in France - but it is also in evidence in a Germany still seeking unification and in a Britain whose Labour Party has recently expressed its restiveness about both atomic weaponry and Britain's American ally. But let us consider for a moment one more explosive factor which I would call the increasing radicalization of diplomacy. What we are witnessing today is the use of diplomacy not to damp down inflammable disputes but to experiment in new methods of creating explosions. We like to think of the Kremlin as the guilty party in this respect, but we ought in all candor to examine ourselves first. The U-2 incident springs to mind. We permitted the military advantages of the U-2 flights to outweigh the political disadvantages which, on discovery, would inevitably come to plague us. When the Soviets did catch up with us, Khrushchev exploded. Had he done the same to us, we too would have exploded. And we compounded the error by making, even if only for a brief and awkward few days, the violation of Soviet air space an officially announced objective of our policy.

These methods and madnesses are not conducive to the peaceful settlement of disputes. But neither, certainly, are the methods of Khrushchev. Brandishing shoes and threats and insults on the floor of the UN injects new poison into the international atmosphere, poison which may be as dangerous as fallout from bomb testing. The Soviet proposals to grant immediate independence to all remaining colonial areas are reckless and irresponsible. In view of what has happened in the Congo they are downright criminal. Let us face it. One of the most explosive and revolutionary factors on the world scene is the Soviet premier himself, who has time and again deliberately aggravated international tensions as a means of promoting his policies.

How do we deal with the dangers that beset us? Here it is possible to suggest only a few guidelines. They are certainly not sufficient to solve the problem, but I believe they are indispensable in dealing with it. First of all, we must enlarge our constituency. Reference was made earlier to our being outnumbered by the massive populations of the underdeveloped world. But we need not be outnumbered if we can make some progress in breaking down the barriers that divide us from this new world. We can do this if we accept responsibility for it, if we develop a sense of obligation very like the obligation which American society and government took upon themselves in the 1930s toward the underdeveloped areas and poverty-stricken people of this country. To use a phrase very unpopular in some circles, we need to launch a global New Deal. The nations of the underprivileged continents will need massive transfers of capital funds and of commodities for direct consumption. They require both direct relief and pump-priming. We in the United States have enough wealth and production capacity to supply a very large part of their needs. We must do a diplomatic job to see that our European and Japanese allies contribute a proportionate share. And by all means let the Soviet Union aspire to cover the remaining demand. This is competition in its most useful sense, in that it eases the immediate burden on us, diverts Soviet resources from more unpleasant uses, and calms those who fear that aid from one side alone means alignment with that side. Above all, it reduces the temptation to resort to desperate measures; it increases hope that somehow the enormous problem of the underprivileged will be mastered. As long as this hope is present, the new countries will be a factor for peace.

But if we expand our constituency we know that our new constituents will be suspicious. We also know that given the fragile governments - and sometimes the corrupt governments - the aid we give may be almost wholly wasted due to inefficient or corrupt practices. Laos comes to mind as an unhappy example. In order to meet this problem we are going to have to induge in a practice which goes by another very unpopular name - intervention. The presence of American capital and technicians in the necessary quantity means intervention. They inevitably have direct impact on the domestic structure of every country receiving them. Surely this is one of the major lessons we can learn from our painful experience with Castro. Quite apart from anything our government did during the Batista regime, the very presence of private American capital and ownership in a large sector of the Cuban economy tended to identify the United States with the old regime. Large economic operations cannot be politically neutral; so that we have the most delicate task of making these operations politically acceptable. And this means that we must be willing to intervene in order to support a socially just distribution of wealth and an honest and humane government. We cannot stand too many Koreas where we let Syngman Rhee run his own show and castigated anyone who dared criticize him until the abuses piled up to the flash-point of revolution.

Where to set limits on intervention is a very difficult question If we develop a real sense of responsibility for the societies we help, limits will suggest themselves. They are the same limits which characterize our domestic political structure in which public welfare and individual freedom are constantly being balanced off against each other. The basic sense of our society has been one of maximizing individual freedom. If we follow that norm in our dealing with other societies, intervention which overreaches itself will be the exception ana not the rule.

Another limiting factor is the presence of the competition. The Soviets and we are in a competition — or we ought to be - for the post of chief admirer of nationalism and national sovereignty. This contest continually offers instruction that one does best to limit his interventionist operations. Sheer prudence sets its own boundary lines in this age of the new nationalism. And we need to recognize that we can have only a limited liability relationship to the new countries. We cannot wholly manage their fates. To try to do so would drive them away from us more quickly than anything else. There must be a certain willingness to let nature take its course and not to insist that we must win every round in every ring. We have enough strength and ingenuity to win the crucial rounds.

The need for intervention is apparent; so is the need for limits to intervention. Here the UN can play its most vital role The more we can channel aid through an international organization the less suspect is that aid and the intervention it represents in the eyes of the recipients.

In order to deal with our explosive environment I have suggested that we must vastly enlarge our constituency and launch a massive development program. But the expansion of political and economic operations is not enough. We must continue to carry out a protective function. It is probably true that the Kremlin would rather compete with us in the arenas of economics, politics and ideology. But this does not mean that Khrushchev would not use force if he judges us to be militarily weak. Hence one can only endorse our stickiness about inspection in the disarmament negotiations which we have carried on with the Soviets at various intervals over the last fifteen years. We cannot rely on Soviet promises. We must be in a position to see that disarmament agreements will without question be observed. And that means adequate inspection. If the Soviets continue to resist inspection, we have no choice but to continue to rely on a nuclear deterrent as an essential part of our effort to maintain peace.

The dangers that an arms race creates are all too apparent, but it is also obvious that the most crucial struggle today is in the realm of politics and economics. Our most vital need is clearly a more imaginative and generous employment of our political traditions and our economic resources. Military deterrence alone will get us nowhere. But military deterrence is an absolutely indispensable part of our strategy as long as we do not have a satisfactory system of inspection and control.

Pending a satisfactory disarmament agreement we must remain strong, buy time, and develop the free world constituency. We must show the Kremlin that the deliberate creation of explosive situations can be at least as harmful to the Soviets as to ourselves. We ought not to forget that Mr. Khrushchev has some explosive situations in his own backyard. Whatever the degree of ideological harmony or hostility, the Soviet Union can never be wholly at ease with its Chinese neighbor. The Soviet bloc has its own set of tensions just as we have ours. In the long run the tensions in the free world may prove to be more manageable than those in the world of the Soviets. Certainly they will be if the West shows the initiative and imagination of which it is capable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureArms Control in a Cold War

May 1961 By GENE M. LYONS, -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Defense on the Economy

May 1961 By GEORGE E. LENT, PROFESSOR -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Teaching

May 1961 By FRANKLIN SMALLWOOD '51, -

Feature

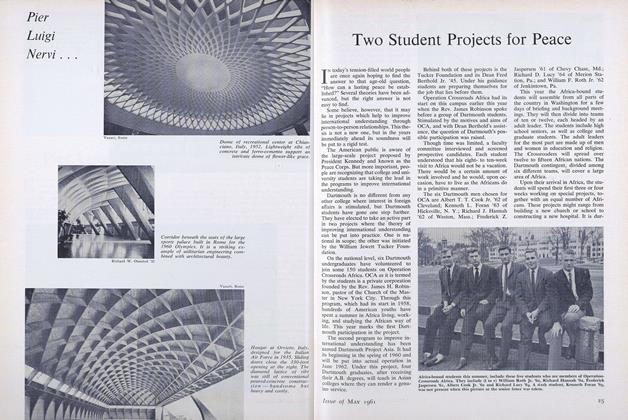

FeatureTwo Student Projects for Peace

May 1961 By D.E.O. -

Feature

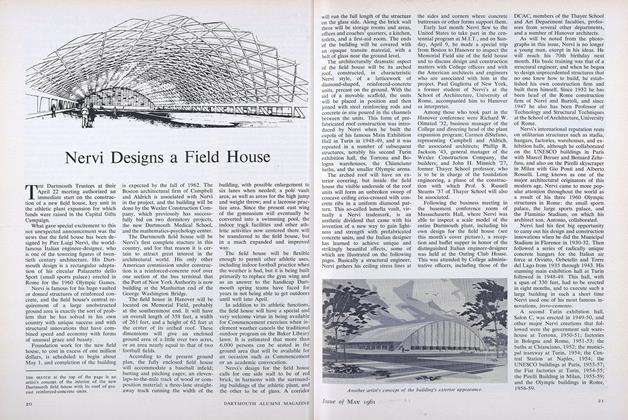

FeatureNervi Designs a Field House

May 1961 -

Feature

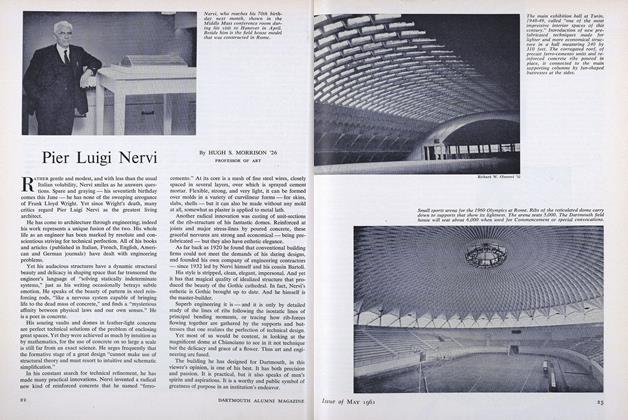

FeaturePier Luigi Nervi

May 1961 By HUGH S. MORRISON '26

RICHARD W. STERLING,

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Hear 1970 Called "Great Year for Dartmouth"

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1975 -

Cover Story

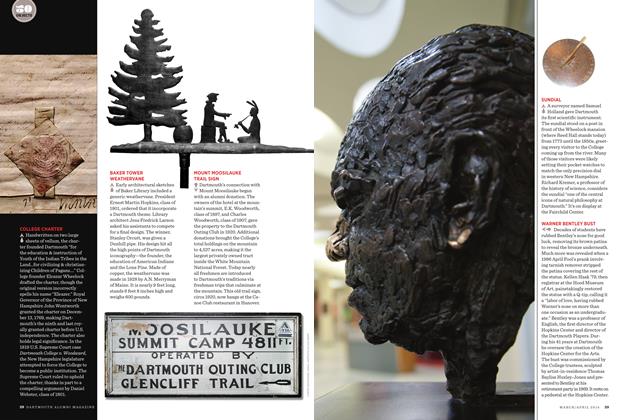

Cover StorySUNDIAL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

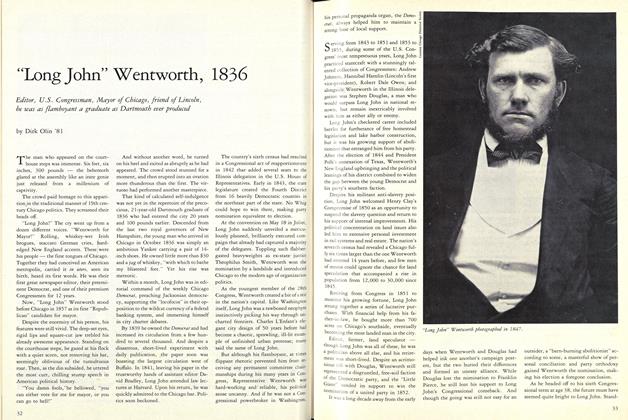

Feature"Long John" Wentworth, 1836

MARCH 1983 By Dirk Olin '81 -

Feature

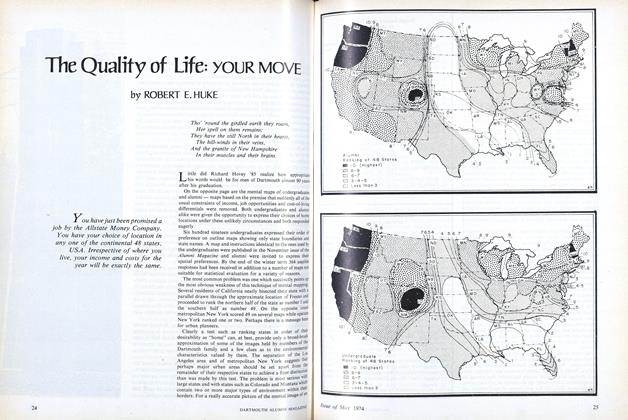

FeatureThe Quality of Life: YOUR MOVE

May 1974 By ROBERT E. HUKE -

Feature

FeatureThe Run

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Stephen Madden