OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS, TUCK SCHOOL

THE staggering burden of defense against the threat of war in the nuclear age profoundly affects the nation's economy. The allocation of a substantial part of our resources to such "non-productive" purposes involves many personal sacrifices and significantly influences economic growth and stability. And the support of our allies abroad has grave implications for our foreign economic position.

National defense expenditures are currently running at an annual rate of about $5O billion and account for about 60 per cent of the Federal budget. Major national security programs for fiscal 1962 are budgeted at $4B billion, including $45.5 billion for the Department of Defense and $2¾ billion for the Atomic Energy Commission. In addition, almost $2 bilhon is being spent on mutual security programs - including defense support, technical cooperation and other assistance programs - and about $1 billion on the cost of space research and subsidies to aircraft and shipping industries believed necessary to national security.

Why Does Defense Cost So Much?

Our national security calls for a military strength which, together with that of our allies, is sufficient to deter any threat ranging from limited emergency to all-out nuclear war. With the development of Russia's nuclear capability, the cost of a nuclear-war deterrent has been superimposed on the cost of forces to meet a threat of more conventional warfare, both "general" and "limited."

One of the most significant changes in the new concept of warfare is the necessity of maintaining a continuous "forcein-being" sufficiently great to insure a deterrent "second-strike." No longer is it sufficient to maintain limited forces and cadres for conventional warfare, with provision for rapid mobilization in the event of an emergency as in the case of Korea. It is clearly much more costly to support such a fully mobilized defense establishment than to maintain stand-by reserves as in the past.

We are now witnessing the most radical changes in military technology in history. Some costly research programs do not achieve their military objectives: nearly fifteen years and one billion dollars have been devoted to the development of nuclear-powered aircraft but the goal is still remote. And the rapid pace of scientific development often renders obsolete a new weapons system before it is operational. Although it cost about $500 million to develop the B-58, it may be superseded by the longer-range and faster B-70 whose development cost will approach one billion dollars. The costly Atlas and Titan Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles probably will eventually be replaced by solid-fuel-propellant missiles such as Minuteman.

The largest share of expenditures, about one-third, is for procurement of the "hardware." Because of greatly increasing complexity, each new generation of weapons costs two or three times the price of weapons they replace. And the phasing in of new weapons entails costly duplication and overlapping with the old.

Although the rapid improvements in technology have made possible reductions in the size of forces, these savings have been offset by higher unit costs involved in operating and maintaining the increasingly complex weapons and equipment. The cost per flying hour and per overhaul for the newer aircraft and ships greatly exceeds that of their predecessors. The cost of maintaining our expanding early warning systems will climb from $4OO million in 1960 to $600 million in 1962. And while the number of military personnel has been virtually stabilized, there are built-in rising costs due to longevity and proficiency pay provisions; retirement pay alone is expected to double, from $1 billion to $2 billion annually, in the next decade.

How Much Defense Can We Afford?

The cost of maintaining such forces currently absorbs about 10 per cent of the gross national product. Because of this drain on our resources, defense policies have been dictated partly by fear of impairing the nation's economy. Although never officially acknowledged, postwar administrations have uniformly imposed dollar ceilings on the Services' estimates of military requirements on the ground that greater expenditures would endanger our economic strength. The reconciliation of defense requirements with budgetary and economic limitations is illustrated by the decisions made in connection with the 1960 budget. Military "requirements," according to JSOP 62 (Joint Strategic Objectives Plan), called for appropriations of $57 billion; the President recommended $41 billion and Congress appropriated $40.5 billion.

The problem of balancing economic and fiscal considerations against foreign policy and military requirements is not unique to the United States. Russia, also, has been forced to make some hard choices between her military and economic programs. Primarily to meet the manpower requirements of her economic plans, the Soviet Union has reduced its military forces from 5.8 million men in 1955 to a new level of about 2.4 million. In announcing a reduction of 1.2 million, in January 1960, Khrushchev stated that "The reduction of Soviet armed forces will produce an economy of approximately 16 to 17 billion rubles a year.... This is a great additional amount for the fulfillment and overfulfillment of our economical plans. To exclude nonproductive expenditures, to seek additional possibilities for the development of the country - this is a task that is faced constantly not only by us but by any state."

While there are economic limits to such a diversion of resources to "non-productive" purposes, economists agree that the present level of defense expenditures is substantially below critical. The United States is enjoying the highest standard of living in history and could absorb a much greater defense eeffort if the cost can be justified by convincing military requirements. As President Kennedy has stated, "Our arms must be adequate to meet our commitments and insure our security, without being bound by arbitrary budget ceilings. This nation can afford to be strong - it cannot afford to be weak." The price is paid in taxes necessary to allocate the resources; if we default here, the price is paid through inflation.

The impThe impact of defense expenditures on economic stability, economic growth and on the international position of the United United States is examined below in broad outline.

How Do Defense Expenditures Affect Economic Stability?

Government expenditures on military goods and services are not normally subject to the fluctuations that characterize private spending. In recent years the Defense Department has aimed aaimed at a stable budget to meet all emergencies rather than varying it with recurrent crises in the international situation. Properly managed, a defense budget of the present magnitude has a stabilizing influence on the economy.

Because of its sheer magnitude, however, failure to keep defense spending under strict control may intensify business cycles. This happened during 1957, when expenditures on major procurement unexpectedly rose, and drastic measures to curb these outlays in mid-year contributed to the 1957-58 recession. On the other hand, in 1958 and more recently the Administration countered recessionary tendencies by stepping up military procurement. Within limits, the rate of expenditures in fulfilling military goals can properly be adjusted to changing economic conditions. For example, military construction expenditures have been accelerated to meet recessions in the private economy, and they can be slowed down during full employment without impairing military strength. However, it would clearly be unsound to allow the size of the military budget to be influenced by non-military objectives such as full employment.

Shifting military requirements that accompany the changing technology leave their impact on industry. The transition from aircraft to missiles, for example, has entailed significant adjustments by established companies and has taken its toll in structural unemployment.

How Do Defense Expenditures Affect Economic Growth?

There has been undue concern over the effect of military expenditures on economic growth. Despite rising defense expenditures, the economy has grown significantly in the postwar period. Between 1945 and 1960 United States output increased at an average annual rate of about 3½ per cent. To be sure, this was a unique period. The rapid increase in population and the tremendous backlog of demand deferred by World War II provided an unusual impetus.

Even with a balanced budget, Government spending in itself has a stimulating effect on the economy. This is because the total income diverted to the government by taxes is spent, whereas part might otherwise be saved (and unspent) by the income recipient. In this way, government spending makes a deficiency of aggregate demand less likely.

It is frequently alleged that economic growth is deterred by a crushing weight of taxes and their indirect effects on incentives to work and to take business risks. But this claim has never been supported by either theory or empirical studies. There is considerable evidence that taxes on wages and salaries, in fact, are quite as likely to increase effort as to reduce it. Little is known about the effect of high taxes on business incentives. While income and profit taxes reduce funds otherwise available for investment, capital expenditures in the postwar period were sustained at record levels.

Defense spending, of course, absorbs a substantial part of our total resources that might otherwise be devoted to the improvement of human welfare. For example, 2½ million persons are absorbed directly in military service; millions of workers and thousands of scientists are diverted to defense activities; and other valuable resources are used up.

But such diversion does not wholly represent economic waste. There are many "spillovers" to the private economy whose benefits are incalculable. Government research has pushed forward the frontiers of scientific knowledge and stimulated a technological revolution in nuclear power, electronics, air and space travel, medicine and other fields. Advances have been made in air transportation and other services which are of great benefit to the private economy. Through its educational training programs, in and out of the Services, the level of skills has been improved. So, in many respects, defense activities have had a double "payoff" in enhancing the growth of the private economy.

Effect on the Allocation of National Resources

It is a matter of some concern how economically the defense establishment manages the resources allocated. Not only may we seriously question the efficiency with which the military conducts its operations; many policies adopted by the government in the name of defense interfere, often unwisely, in the most efficient allocation of the nation's resources.

In the management of defense, subjective decisions are involved in the spending of the funds budgeted. Unlike the private market economy, there is no built-in mechanism to assure their optimum utilization. Too, the major defense industries are not operated with the same degree of efficiency that characterizes production for a competitive market. As a result the military dollar is not stretched as far as the dollar spent on private goods. A recent study of procurement practices, conducted by the Joint Economic Committee, concluded: "Our economy can and must bear any necessary defense expenditures for the present and for the long pull ahead.... However, the economy should not be required to shoulder the great burden of waste and inefficiency that has characterized the duplicative and overlapping military supply and service systems for the last two decades." The Committee estimated that billions of dollars a year could be saved by improved organization and control.

Other policies adopted in the name of national security are no less costly to the economy, and should be reexamined in the light of nuclear warfare. These include import controls, subsidies, tax policies, stockpiling and other measures that were instituted to insure against a type of war that is least likely to occur and in which the United States would have an advantage anyway.

Outstanding among these are the tax subsidies and import controls that were designed to strengthen our oil and mineral resources. Tax benefits, such as percentage depletion, to encourage the development of domestic oil arid ore reserves cost the Treasury more than $1 billion yearly. At the same time rigid import controls are being imposed to curb the use of foreign oil that is considerably cheaper to produce. Although military planning does not rule out the possibility of a long general war, as a result of the nuclear deterrence, domestic proved reserves of oil are greatly in excess of requirements for present planning purposes.

The government also subsidizes the U. S. shipbuilding industry to meet foreign competition. (The purpose of this subsidy, first enacted in 1936, was to provide a mobilization base for the expansion of our merchant marine in a war emergency.) Since the same vessel can be built at half the price in foreign shipyards, this subsidy is expensive. The cost of replacing our present subsidized merchant marine over the next ten years is estimated at between $4 billion and $5 billion, of which the government will pay about half.

Interference with the private market economy represented by these controls and subsidies is costly to the American people and does not appear to be justified by modern concepts of national defense.

The Impact on Our International Position

The United States' world-wide mutual aid program and deployment of forces has added a new dimension to the nation's defense problems. Defense expenditures arising from mutual-security assistance grants and the support of our bases and troops stationed overseas have contributed seriously to a deficit in balance of payments and the drain of gold abroad. The magnitude of this problem is evidenced by the shrinkage in our gold stock since 1957 from $23 billion to less than $17½ billion, a loss of over $5 billion in about three years.

The principal source of the payments deficit is the heavy drain of expenditures involved with the construction and maintenance of military bases abroad and the support of our forces, including expenditures by the troops and their families. Such payments now amount to over $3 billion a year. This has been approximately the size of our payments deficit, represented by an increase in foreign dollar balances and an outflow of gold.

Such military disbursements, of course, are not the only source of our payments deficits and gold drain. Our capital movements abroad, involving U. S. foreign investment, also contribute. They are, nevertheless, a significant factor that is subject to government control, and a matter of grave concern to our national defense policies.

This adverse situation can be corrected only by a reduction of our forces abroad or by shifting part of the burden of their support to foreign countries concerned. While a reduction in forces would be consistent with the development of long-range bombers and intercontinental missiles based in the United States, political considerations militate against such a step. Therefore, our allies in Europe, especially Western Germany, are being urged to shoulder a greater share of the cost of maintaining U. S. forces deployed there.

What Does the Future Hold?

The arms race has become a titanic struggle between two rival economic systems to maintain a balance of terror that will deter the outbreak of a nuclear war. This contest has stimulated the economic growth of the United States as well as that of Russia, and thereby further enhances their respective capabilities to produce greater numbers of more deadly weapons.

In this race the Communist bloc appears to be fast catching up with if not surpassing the Free World in some respects in advanced technology and economic strength. Russian industrial capacity is growing at an annual rate of 8 to 10 per cent, against an increase of only 3 to 4 per cent for the United States.

Attempts to match advances in Soviet military strength with greater defense expenditures are likely to evoke more intensified Soviet efforts. The only way out of this vicious circle is an international agreement on arms control.

It is ironical that one of the obstacles to effective disarmament is the fear of adverse economic effects. We well remember the economic readjustments that accompanied demobilization after World War II. But such anxiety is unwarranted. If a curtailment in military expenditures is accompanied by proper economic planning and budgetary adjustments, the way would be opened to even greater economic growth and higher living standards. The post-Korean fiscal policy that balanced off cutbacks in military outlays with tax reductions shows that this can be done effectively.

Our national defense policy in this respect was well stated in President Kennedy's special message to Congress on defense spending. Recognizing that the basic problems of the world today are not susceptible to a military solution, he said, Neither our strategy nor our psychology as a nation - and certainly not our economy - must become dependent upon our permanent maintenance of a large military establishment. Our military posture must be sufficiently flexible and under control to be consistent with our efforts to explore all possibilities and to take every step to lessen tensions, to obtain peaceful solutions and to secure arms limitations. Diplomacy and defense are no longer distinct alternatives, one to be used where the other fails - both must complement each other."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureArms Control in a Cold War

May 1961 By GENE M. LYONS, -

Feature

FeatureThe Human Revolution and World Peace

May 1961 By RICHARD W. STERLING, -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Teaching

May 1961 By FRANKLIN SMALLWOOD '51, -

Feature

FeatureTwo Student Projects for Peace

May 1961 By D.E.O. -

Feature

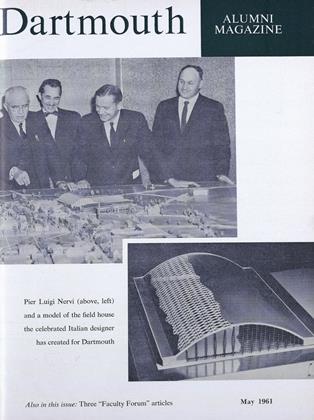

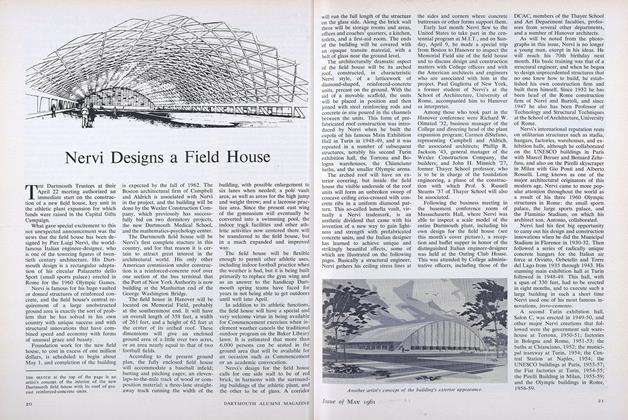

FeatureNervi Designs a Field House

May 1961 -

Feature

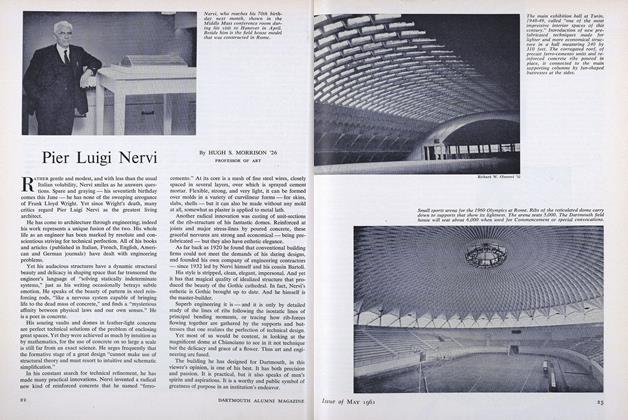

FeaturePier Luigi Nervi

May 1961 By HUGH S. MORRISON '26

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE THEME IS CHANGE

April 1962 -

Cover Story

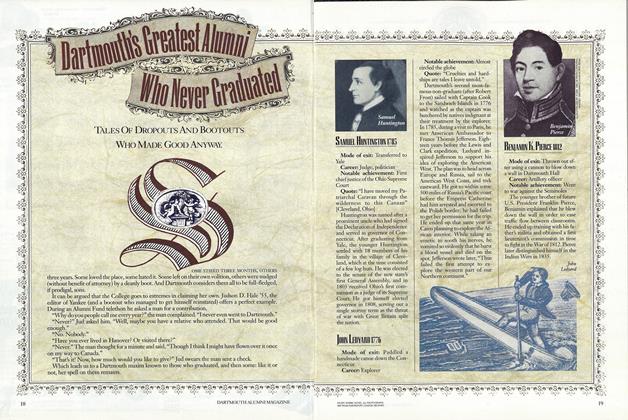

Cover StoryTales of Dropouts And Bootouts Who Made Good Anyway.

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureThe Parent Trap

Mar/Apr 2011 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Cross Section of Existence

MARCH 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureThe Left Fielder's Glove

March 1996 By JOHN MONAHAN -

Feature

FeatureAre Marriage and College Compatible?

March 1960 By MARGARET MEAD