ByWilliam Cahn '34. New York: Harper andBrothers, 1961. 254 pp. $4.50.

Critics of the American business system, both at home and abroad, sometimes seem to take a dim view of the very notion of success itself. But often these same critics fail to look clearly at the process leading to the success, and this process is vitally important in understanding the electrifying growth of business in America. While the history of Pitney-Bowes readily meets the usual criteria of a "success story," the process whereby the firm achieved prominence is in itself worthy of the analysis given it in this book.

A struggling inventor (Pitney) met an effusive salesman (Bowes) shortly after World War I; a company was formed. Its product, a postage meter device, was first greeted with skepticism by the Post Office Department, whose approval was crucial. After agonizing delays and vacillations, clearance came (1920). But within a year joy turned to panic, for on the eve of a proposed stock offering to the public, the Post Office Department undercut its previous pronouncement by agreeing to accept any first-class mail printed with a prescribed indicia (in lieu of a postage stamp), regardless of the means by which the mailer presented it. Gone was the unique advantage of the company's product: the separately-contained, tamper-proof recording device of the postage meter. Gone, also, was stock-offering opportunity.

The competition between the small number of postage meter manufacturers and a larger number of permit printers (whose devices contained no Post Office-authorized recording meter) waged furiously through the 1920's. In the process, Pitney and Bowes found their personal relations wearing thin. Pitney resigned, immediately formed a new permit machine company, a direct competitor to the firm still carrying his name. Finally, in 1928, both the general ambiguity between the postage meter and the permit machines and the personal differences between Pitney and Bowes came to a head in a climactic series of hearings in Congress. Pitney contributed a bombshell by writing a letter to the Congressional committee repudiating the very advantages of the meter he himself had developed. But after a series of bitter hearings, the committee ended by making a clear-distinction between metered mail and permit mail, thereby allowing each to develop along separate lines emphasizing separate assets.

With this green light, Pitney-Bowes rapidly moved to a dominant position. Corporate growth brought new demands internally. Bowes tired of the demands of administrative detail, and a fresh corporate personality attuned to modern management methods came through the leadership of a new president, Walter H. Wheeler. The concepts of employee communication, profitsharing, and efficiency brought by Wheeler led Stuart Chase, in his introduction to this book, to conclude that "no company will better reward study in the fields of employee and community relations... Here is a model for a civilized industry within a civilized, open society...."

Success in the market was overwhelming. By the late 1950's, the company's meters handled almost half of all United States mail. Not only was Pitney-Bowes the world's largest manufacturer of postage meters, it also made almost 100% of all machines used in the United States. Inevitably, the latter fact came under scrutiny of the antitrust division of the Department of Justice; a consent decree resulted that provided that any manufacturer approved by the Post Office Department would be licensed by Pitney-Bowes, and existing patents ma< available free of charge. Competitors will have to come, for, as the author puts it, "Pitney-Bowes was thus given the responsibility of guaranteeing that competitors would be restored within the industry within the next ten years." But the success of the company, internally and externally, will be hard to match.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

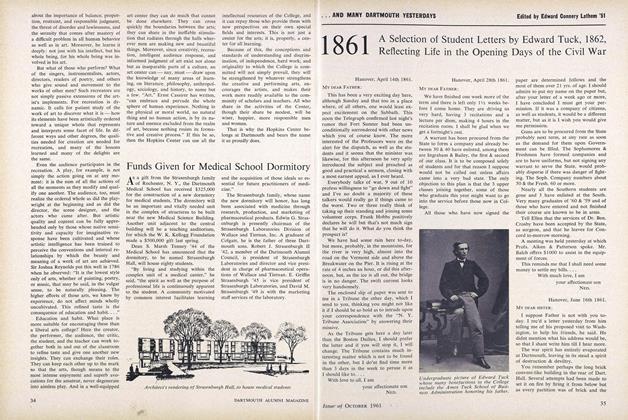

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

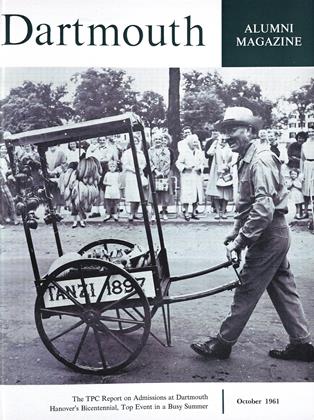

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureWHY a Hopkins Center at Dartmouth?

October 1961 -

Feature

FeatureWHAT OF ADMISSIONS AT DARTMOUTH?

October 1961 -

Feature

FeatureADMISSIONS – As Seen at the President's Desk

October 1961 By J.S.D. -

Feature

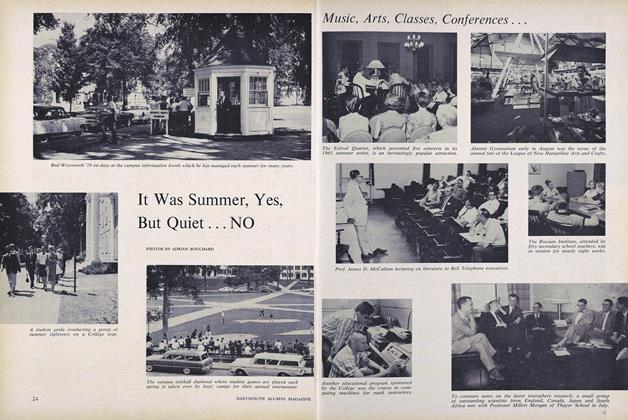

FeatureIt Was Summer, Yes, But Quiet... NO

October 1961 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

WAYNE G. BROEHL JR.

Books

-

Books

BooksRecommended Books

April 1931 -

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

February 1935 -

Books

BooksSHADOWS ON THE LAND — AN ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY OF THE PHIL IPPINES.

MAY 1964 By ALBERT S. CARLSON -

Books

BooksGRANITE and SAGEBRUSH,

February 1945 By L. B. Richardson 'OO. -

Books

BooksMOLIERE ET SES AMIS ET LES GAIETES DE LA CONSIGNE

April 1951 By R.C. NEMIAN -

Books

BooksENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES: POPULATION, POLLUTION, AND ECONOMICS

March 1974 By RJCHARD D. SHEAFF '66