Critics call him the Cassandra of American politics, but this year's Montgomery Fellow says a hard look is just what this country needs.

Here is a tale of two high school graduations. When I received my diploma in 1953,1 inherited from my parents the richest and most productive economy that history had ever seen. Every year of my grandfather's life, and every year of my father's business career, America ran up trade surpluses. We had 44 percent of the world's economic product when I graduated, and our economy was eight times larger than Japan's. When I graduated from high school, "Made in Japan" meant junk. We produced 80 percent of the world's automobiles and our students were receiving the highest test scores in the world.

I took the generational baton from my parents and I looked over my shoulder and there was no one in sight.

My son Scott graduated from high school a year ago and inherited from my generation a $2.5 trillion federal deficit. Two weeks after his graduation ceremony America became the world's largest debtor nation. The nation's productivity sank to the lowest growth rate in the industrialized world. American students now rank in the bottom third in educational testing. And Japan's reputation has changed. Hewlett Packard recently found that its poorest Japanese supplier was six times more reliable than the best American one.

The moral of this story should be clear. The United States is not structured for long-term success. It is structured for long-term decline. History's kaleidoscope has turned we were hardly noticing but the pattern that emerges reveals a whole new world. Our destiny is no longer manifest. The nation must learn what it takes to live in the new international marketplace. We must not only have competitive industries but we must have competitive institutions including those below.

Legal System

The international competitiveness of the United States is affected by its litigiousness the greatest on Earth. Japan trains 1,000 engineers for every 100 lawyers; our nation's rate is the reverse. Two-thirds of all the lawyers in the world practice in the United States. Lloyds of London estimates that 12 percent of its business is here along with 90 percent of its insurance claims.

This litigiousness adds to the cost of American goods as assuredly as does our inefficient management and labor. U.S. airlines, for instance, had to pay $600 million for passenger liability a few years ago; today it is more than $1 billion and rising fast. This alone can make U.S. airlines uncompetitive.

Litigation also dampens entrepre- neurship. It clearly discourages American business from taking risks, retards innovation and imagination. Society's passion for law also drains off brains and talent desperately needed elsewhere. Forty percent of Rhodes Scholars go to law school. You can't sue a nation to greatness.

Health Care

Chrysler spends $550 per automobile on health-care costs, a sum that far exceeds those of its Japanese competitors.

What does all this spending get us? One of the least efficient health-care systems in the world. The United States has 200,000 excess hospital beds. By the year 2000 we will have an estimated 145,000 surplus doctors. Costs are rising three times the rate of inflation and now consume 11.5 cents of every dollar we spend. Our health care is making our nation economically sick.

Tax System

America depends on direct taxes that give an advantage to imports and penalize exports. Our international competitors have a value-added tax, or its practical equivalent. These taxes are rebated to exporters but not to importers. The U.S. tax system encourages consumption and puts our goods at an economic disadvantage.

The system's complexity also bedevilsus. Tax shelters are now a $20 billion industry. Approximately 300,000 of our best and brightest young men and women are employed to advise Americans on shelters. Tax reform is often thought of as a domestic issue, but its ramifications go to the heart of our international competitiveness.

Costs of Capital

Our national savings rate is shrinking and now stands at an all-time low. Because we save so little per capita compared to our industrial competitors, access to capital costs American industry three times more than our competition pays.

Education

In a competitive world, an educated citizenry is a nation's most valuable resource. Yet, with approximately 23 million functionally illiterate adults, the United States has the largest number of any industrial country. In a report titled "A Nation at Risk," the National Commission on Excellence asserts that America has committed "acts of unilateral education disarmament."

An average eighth grader in Japan knows more mathematics than a graduate of a master's of business administration program in the United States. Japanese students go to school 240 days a year while U.S. students go 180 days a year. The net effect: the average student graduating from Japanese high schools has spent more than three years' additional time in a classroom and has a significantly higher IQ than the average American student. On top of that, Japan graduates 95 percent of its students from high school while the U.S. graduates fewer than 75 percent.

Crime

New York City alone has twice as many homicides as all of Japan; the United States is the most violent and crime-ridden society in the industrialized world. This affects our international competitiveness. No other society requires its citizens and businesses to spend as much on burglar alarms, security officers and internal security. American businesses in one recent five-year period had to hire 602,000 security officers, an expense that must be added to the overhead of American goods.

The societal costs of the nation's crime wave are enormous. Japan's taxpayers support 50,000 inmates (including suspects awaiting trial), while U.S. taxpayers support 580,000 adult prisoners.

Related to crime is the problem of drugs. Studies show that as many as 20 percent of American workers use drugs at the workplace. Some 500,000 Americans use heroin, 20 million smoke marijuana fairly regularly, and five to six million people use cocaine. Such figures can hardly be conducive to quality products.

Defense Expenditures

A nation that spends little on defense can afford to concentrate its public and private capital on international competitiveness. Conversely, a nation that supports a large defense finds its goods increasingly uncompetitive. The United States spends seven percent of its gross national product on defense. Japan spends less than one percent.

Seventy percent of U.S. programs in research and development and testing and evaluation are now defense related. About 40 percent of all our engineers and scientists are involved in military projects, while virtually all of Japan's and Taiwan's scientists and engineers are engaged in bolstering their domestic economies.

In 1984 the United States spent more to invent the B1 bomber than our steel industry did on all research and development. While we spend an increasing amount of research in the effort to make our military stronger, the Japanese dedicate their science to producing innovative goods that weaken our economy further. Military power is purchased at the expense of economic power.

Political System

No industrialized society spends as much to elect and influence its politicians. The average candidate for the U.S. Senate in 1984 raised and spent $3 million. It is estimated that well over $1.5 billion a year is spent trying to influence Congress and the bureaucracy through the nation's 8,800 registered lobbyists. Most of this money is a business expense.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Congress involves itself increasingly in frivolous subjects. In 1960, the House of Representatives had 180 roll calls (.7 votes per working day); by 1980, the number had risen to 1,276 roll-call votes (3.9 votes each working day).

Indeed, a number of thoughtful people Lloyd Cutler, James McGregor Burns and Douglas Dillon among others have raised the question whether our nation is structurally able to solve its problems. The American political system is simply not organized to make hard choices.

Race and Ethnicity

This continues to be an almost taboo subject in America. But we must broach it. Twenty-five to 30 percent of all four-year-olds in America are black or Hispanic. These children are our future. If they succeed, we succeed as a nation; if they fail, we shall have a social and economic burden of nation threatening proportions.

The illegitimacy rate among blacks now stands at more than 50 percent and is increasing. Approximately 44 percent of black teens and 56 percent of Hispanic teens are illiterate. Nearly 50 percent of all Hispanic youths in America never finish high school. One study has shown that 46 percent of this nation's black males over 16 are jobless.

Blacks account for 12 percent of the U.S. population but 46 percent of arrests for violent crimes. In 1982, 49.2 percent of all murders and non-negligent manslaughters known to police were committed by blacks often against blacks. Hispanics account for six percent of the U.S. population but 12 percent of all arrests for violent crime.

These numbers are a social time bomb. If we don't act, we will see an America that has two angry, underutilized and undereducated minority groups existing unassimilated within our borders. This nation will not remain economically competitive if our rates for crime, welfare, adolescent parenthood, high-school dropouts, and illiteracy remain so much higher than in other industrialized nations.

I believe that many of America's solutions lie in a political no man's land where both parties fear to tread. As the Roman historian Livy said, "We can neither bare our ills nor their cures." But a problem ignored is a problem made worse. I believe that America has to take on some of its own sacred cows. We must reform military pensions, and veterans' benefits, and civil service benefits. We must drastically streamline the health-care system to make it more efficient and to cover more people more effectively. We must look at our whole legal system to find ways to delawyer our society no-fault automobile insurance, tort reform, mediation.

We must look at the social-security system raise the retirement age, and start taxing social security benefits for the middle class and the wealthy. We must start a national dialogue about what we want from our medical technology. We must be wise enough to use the machines we were wise enough to invent. In short, I believe that America must reform all of its institutions and spend at least a generation restarting our economic engines.

The wealth of nations is not found in its Dow Jones average. It is in the productivity of its workers, cost of its capital, excellence of its education, cost of its health care, efficiency of its institutions, patterns of investment and the viability of its political system. America is becoming increasingly uncompetitive by these standards. The solutions do not lie in quality-control circles or "just in time" inventory systems, but in a major sustained reform of all its institutions.

The United States is notstructured for long-termsuccess. It is structuredfor long-term decline.

No other society requiresits citizens and businessesto spend as much on burglar alarms, security officers and internal security.

Until he came to Dartmouth last winter,Richard D. Lamm was governor of Colorado. This article was adapted from an address he gave on campus in February.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryLooking for Mr. Goodjob

May 1987 By Jock McDonald '87 -

Feature

FeatureA Spanish Galleon's Real Treasure

May 1987 By R. Duncan Mathewson III '60 -

Feature

FeatureThe Official Dartmouth Reunion Guide to Greenspeak

May 1987 -

Sports

SportsA Fast-Balling Junior Mulls Going Pro

May 1987 By Jim Needham -

Article

ArticleStan Brakhage '55: "The Picasso of Cinema"

May 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

May 1987 By Kenneth M. Johnson

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Launches General Campaign Among Alumni

OCTOBER 1969 -

Cover Story

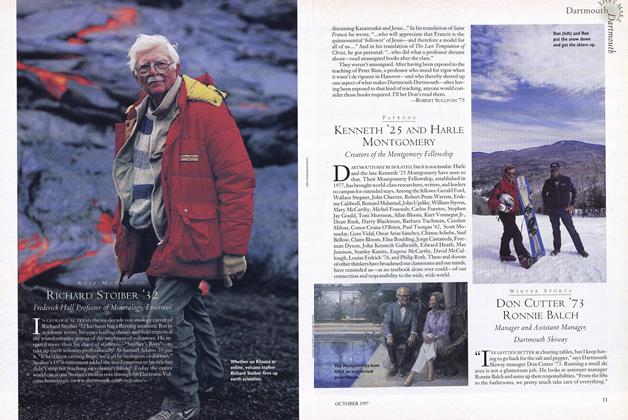

Cover StoryKenneth '25 and Harle Montgomery

OCTOBER 1997 -

FEATURES

FEATURESSian Beilock

MAY | JUNE 2023 By ABIGAIL JONES '03 -

Cover Story

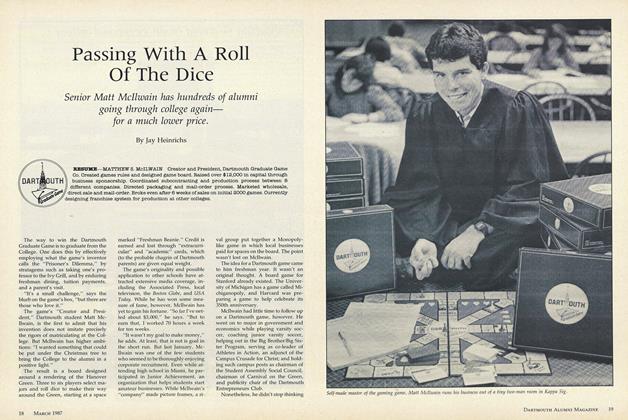

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

MARCH • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureStory Time

MAY 1991 By Nancy Millichap Davies -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WASH YOUR DOG LIKE A PRO

Jan/Feb 2009 By RUSH '05 & JAMES TURNER '04