The Gatekeepers

Admit? Wait list? Deny? A behind-the-scenes look at how admissions officers at a premier college make their decisions.

Nov/Dec 2002 JACQUES STEINBERG ’88Admit? Wait list? Deny? A behind-the-scenes look at how admissions officers at a premier college make their decisions.

Nov/Dec 2002 JACQUES STEINBERG ’88ADMIT? WAIT LIST? DENY? A BEHIND-THE-SCENES LOOK AT HOW ADMISSIONS OFFICERS AT A PREMIER COLLEGE MAKE THEIR DECISIONS.

Colleges make their admissions decisions behind a cordon of security befitting the selection of a pope. The reasons why one applicant is accepted while another is rejected are closely held by the few people permitted in the room at the time the choices are made. And soon after issuing their one-word rulings—yes, no or maybe—admissions officers usually feed the evidence of their deliberations into Iran-Contra-era document shredders. The raw materials that fuel such discussions—test scores, race, social class, grades, athletic ability, family connections—are considered far too combustible to be combined in front of the applicants themselves, let alone a wider audience.

To penetrate this mysterious culture, I spent eight months, from the fall of 1999 until the spring of 2000, as an observer inside the admissions office of one of the most selective colleges in the country, Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. I then mined that experience to write a series of articles that appeared on the front page of The New York Times. As part of my research, I peered over the shoulders of the Wesleyan admissions staff as they sorted and evaluated 10 times as many applications as there were seats available in the class of 2004. At the moment that these sentries were turning back most of the teenagers massed at the university's front gate, so, too, were their colleagues at Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Dartmouth and dozens of other elite institutions. Each received a record number of applications in the winter of 2000. And each would whittle its lists of applicants down in strikingly similar ways.

My book The Gatekeepers grew out of that newspaper series. Specifically, it tells the story of one admissions officer, Ralph Figueroa, and the high school seniors whose cases he and his colleagues considered that year. My goal in writing it was to allow any outsider including those teenagers hoping to gain access—to follow along as actual applications pass through each stage of an entire admissions cycle at an elite private college.

In granting me such privileged access, Ralph Figueroa and his colleagues have enabled me to describe the high drama of selective college admissions in a way that no "how-to" book ever could. Although Wesleyan, Dartmouth and other colleges have adapted numerous techniques from social science to help them sift each year's freshman class, their judgments are just as often intuitive and idiosyncratic. It's actually quite a messy process, and only by watching admissions officers wrestle with the attributes of an actual candidate can an outsider grasp the various, sometimes competing institutional priorities in play. Similarly, only by listening closely to teenagers and their parents can one appreciate why so many applicants from so many different backgrounds came to concentrate their pleas for acceptance on such a small collection of private colleges in the late 20th century. By then the prize that those families were pursuing, the first-class private education described in the brochure for the American Dream, had become at once more accessible, and more elusive, than ever.

AMONG THE QUESTIONS THAT INFORMED MY REPORTING

for The Gatekeepers is one that has stumped me for nearly 20 years, ever since I applied to Dartmouth, my own dream college: How had I managed to get in, when so many others had not?

I knew I wanted to attend Dartmouth since at least the age of 13. I'm not sure if I was aware then that Dartmouth was part of the Ivy League, for my immediate concern was the appeal of its campus. It was located 25 miles from the summer camp in Piermont, New Hampshire, that my brother and I had attended for nearly a decade. One summer eight bunk mates and I spent four rainy days and nights on the Appalachian Trail, attempting to hike up and over the range of mountains that lay like an obstacle course between Camp Walt Whitman and Dartmouth. Once we finally arrived in Hanover and sought shelter in a shop called the Ice Cream Machine, none of us wanted to leave. Attending Dartmouth, I figured, would be like finding refuge in that shop.

One morning during my senior year of high school, my parents and I rose at dawn and drove four hours from our home in southeastern Massachusetts to Hanover. Once on the Dartmouth campus, we scaled the thick granite steps of McNutt Hall to attend a general information session led by an admissions officer, the first admissions officer whom I had ever seen. Sitting in a hard-back chair on carpeting that was as well-tended as a putting green, I counted more than 100 other applicants in the audience, each of whom looked as nervous as I was. By then I knew all about the Ivy League and where Dartmouth stood in the nations academic pantheon, at least as scored by U.S. News &World Report. As I gazed up at a towering oil portrait of a balding man wearing a severe expression—You don't have a prayer, he seemed to be saying to me—I wondered how I would ever be able to distinguish myself in this company, particularly since Dartmouth discouraged on-campus interviews . My mother, however, had al ready considered the problem, and at the conclusion of the admissions officer's talk grabbed me by the elbow and dragged me to the front of the room.

"We're the Steinbergs," she told the officer, a smile on her face and her eyes piercing his meaningfully. From the gravity of her tone, the officer must have thought he was about to have an audience with one of the Kennedys, rather than the son of a Jewish anesthesiolo gist and his wife, a nurse who had abandoned her profession because she grew woozy at the sight of blood.

When the thick letter filled with good news arrived from Hanover months later, my mother was half-convinced that her introduction had made a difference. At the very least, she figured, the officer must have noted the depth of this particular mothers love for her son. For my part, I was both gratified and mystified by Dartmouths interest in me. In 1983, the year I applied, nearly 9,000 applicants had sought about 1,000 seats in the freshman class. And most of those accepted had better SAT scores than I did.

Had my essay pushed me over the top? Asked to reflect on something I had read recently, I chose a column that Russell Baker had published one Sunday in The Times Magazine, in which he described having his credit cards stolen by someone who had then spent thousands of dollars on first-class airline tickets. Baker had written: "In today's world, you are not who you are named; you are what you are numbered." That sentiment certainly spoke to me, a 17-year-old obscured by a haze of standardized test scores, and I said as much in my essay. Had the admissions committee, despite its insistence that I take all those tests, secretly agreed with me?

What about my high school? The same year I was accepted, a friend from my hometown was rejected by Dartmouth, even though she had attended one of the top prep schools in New England and had better SAT scores than I did. Her school sent a half dozen graduates to Dartmouth each year. I attended a public high school in a small town, and only about half my classmates even applied to college. The last person I was aware of who went to Dartmouth from my high school had graduated years earlier, and he was a star quarter back. I wrote for the newspaper. Had I gained an edge over my private-school counterparts sheerly by virtue of demographics?

The college admissions process rarely affords an opportunity to answer such questions. How many among us even get the chance to meet an admissions officer? (As it turned out, my freshman advisor was Anthony Rud '75, who worked in the admissions office, but if he knew how I got in, he wasn't saying.) My curiosity lay dormant for more than a decade, but was suddenly awakened in the fall of 1999. By then I had become an education writer for The NewYorkTimes. And after four years covering the New York City public schools, I was being promoted to the national education beat. Higher education was now part of my portfolio. One of the first ideas I began pursuing was an occasional series that would be set inside the admissions office of a top college during the coming school year.

In seeking out a setting for these pieces, my criteria were, of course, as subjective as those of the admissions officers and the applicants themselves. Among my parameters was that the school be within two hours' drive from Manhattan, so that I could still report for The Times on other areas of education. And while I would interview admissions officers throughout the Ivy League, I hoped to establish my base camp elsewhere. I knew that the admissions officers under the most pressure were those working at colleges that had caught fire almost overnight—colleges that had neither the time nor the means to bulk up their admissions staffs in response to their sudden popularity.

Most of the dozen or so colleges I approached refused, fearing my presence would somehow compromise the process. And they were understandably concerned about having the mechanics of how they made their most sensitive decisions revealed to a large audience, one that would include trustees and wealthy alumni. And then there was Wesleyan. Founded by Methodist ministers and the fathers of a small Connecticut town in 1831, Wesleyan had long ago matured into a liberal arts powerhouse, if not necessarily a force on the football field. Few colleges could challenge its reputation for excellence, though one loomed only 27 miles to the southwest, in New Haven.

Wesleyan clearly fit the-definition of a hot school with an over worked admissions office. When Maureen Dowd, then a reporter for The Times, visited Wesleyan for several articles during the 1985-1986 school year—the dean of admissions at that time was Karl Furstenberg, who now occupies that job at Dartmouth—the university received 4,900 applications, a number that dipped to 4,400 in 1990. During the next 10 years that figure would grow to nearly 7,000. Over the same period the admissions staff wading through that pile of applications grew by only one member, and now stood at 10. In practical terms, that meant that because every application was read by at least two officers, each officer was responsible for dealing with nearly 1,500 applications—mostly in the eight weeks between early January and early March. Little wonder that faculty members and seniors were occasionally enlisted to give an application its first read, to help lighten the burden.

Wesleyan required that applicants submit SAT scores, and like almost every other selective college, it interpreted those scores differently for each applicant, based on that applicants race, the educational attainment of his parents, the quality of his high school and those extracurricular skills that he or she might bring to campus. Wesleyan also assigned numerical ratings to applicants in amorphous categories such as "commitment" and "intellectual curiosity." Dartmouth, Williams, Michigan and many other colleges compiled similar ratings, and I was curious to see the calculations that went into such assessments.

Wesleyan and I agreed that for my benefit, and that of the readers, I should shadow a single officer as my guide. Four of the possible candidates were effectively disqualified because they had just arrived and would be learning their jobs. Id like to say I used a scientific method to pick from among the five veterans, one of whom was acting as dean. But because I was determined to spend long periods of time with an admissions officer reading applications at his or her home—a crucial part of the process that I had never seen described in print—my criteria boiled down to one: the admissions officer tapped could not have a dog or a cat, because I was allergic.

That pretty much narrowed the field to Ralph Figueroa. A native Californian, Ralph had worked as an admissions officer at Wesleyan for five years, and at Occidental College in Los Angeles for the previous three years. Prior to that, Ralph was a lawyer. As it turned out, his resume was as representative as anyone else's of the typical admissions officer. The previous occupations of Ralphs colleagues at Wesleyan included a food stamp interviewer, resident administrator in a psychiatric halfway house, high school English teacher, management trainee at Sears, and dog catcher.

ON A SUNDAY LATER THAT OCTOBER, RALPH FOUND HIMSELF

on a plane bound for Albuquerque, New Mexico, as part of a recruiting mission. In the Wesleyan admissions office, as at other top colleges, much of the first two months of the fall was devoted to scouring the country for desirable applicants, and Ralphs territory included California, Arizona and New Mexico. For nearly six weeks he had been shuttling around the region. As he drove from one school to the next, sometimes as many as five in a day, he wore a gray business suit, white starched shirt and deep red tie. He typically sat hunched over the steering wheel of a rented compact, which was too small to contain a body that unfolded to more than six feet and weighed well over 200 pounds. With his thick, blown-back black hair, which he would neatly arrange just after daybreak at whatever chain motel he was staying in, he looked like someone on his way to sell a $350 vacuum cleaner rather than the product of a $35,000-a-year education that came with the unwritten guarantee of a happy and meaningful life.

After his plane landed in Albuquerque, Ralph walked to the Hertz counter and rented a coffee-colored Lincoln Navigator, the biggest sport utility vehicle on the lot. While the car was built for someone his size, comfort was less a priority than traction. Ralph had been told that he would need a four-wheel-drive transmission to get where he was going, even without the few inches of early snow that had fallen that morning.

His immediate destination was the Native American Preparatory School (NAPS), a tiny private high school in northeastern New Mexico that had been founded only four years earlier by Richard P. Ettinger 44, an heir to the Prentice-Hall publishing fortune. (Ettinger died in 1996.) The program was set atop a mesa at an altitude of 6,500 feet. It was so new and remote that few admissions officers even knew about it.

The goal of Ralphs mission was straightforward: He was seeking to be the first admissions officer in recent memory to recruit a Native-American teenager to Wesleyan. As far as Ralph could tell, it had been years since the school had made an active effort to bring a Native American to campus, and no Wesleyan student in the fall of 1999 identified himself as such. Several of Ralphs colleagues had told Ralph that he was wasting his time. Why would someone want to go to college in a place so isolated from his culture? But Ralph countered that Wesleyan should try to broaden its definition of diversity beyond the more traditional cultures of Hispanic, African American and Asian-American students. Dartmouth and Stanford were among the few colleges that sought out Native-American students. Why should Wesleyan not do the same?

Ralph felt not only that a Native-American student could learn much from Wesleyan, but that Wesleyan could learn much from him or her. He knew, though, that achieving his goal would be as arduous as the drive that lay before him. The first hour of his journey was easy enough—all highway as straight as a ruler. But once he exited the highway about a half hour north of Santa Fe, Ralph began climbing a steep, rocky, unpaved road that seemed to never end. Finally he saw the tiny green sign for the school and made a sharp right turn into what he thought was paradise.

Ralphs initial impression was that the air enveloping the mountaintop campus was as sweet as any he had ever breathed. His nose filled with the smell of juniper, cedar and pinons. Everywhere were peach, plum and pear trees, from which the students often plucked a midday snack. The campus buildings were dark-tan adobe, with terra cotta floors inside and wood porches outside propped up by thick logs stripped of their bark.

Ettinger had founded NAPS with the hope that it would one day lure someone just like Ralph. A half century earlier Ettinger himself was a typical student at Dartmouth, a white male of some privilege. But he had never forgotten that. when it had been founded in 1769, his alma mater had been established to train a very different type of student: Its original mission was to educate Native Americans. As the 20th century drew to a close, Ettinger felt that mission had taken on new urgency, for while Native Americans represented about 5 percent of American college students, less than half of them were succeeding in graduating from four-year colleges.

To create an intimate setting that would prepare at least some of those students for the rigors of college, Ettinger purchased this 1,600-acre ranch. In the spring before Ralph's visit, 15 members of the Native-American school's first senior class had graduated, and were now attending schools such as Stanford, Macalester and the University of Arizona. Seeking to follow in those footsteps, four current seniors met Ralph over a meal of spaghetti in the school's cafeteria. Ralph gave a broad presentation similar to the one he had given at dozens of high schools during the previous few weeks. But when he got to one of the more tantalizing parts of his stock spiel—the segment where he talks about Wesleyans Hollywood connections Ralph realized he had met his match.

When Ralph mentioned that Jon Turtel taub, a graduate of the Wesleyan class of'85, had directed Instinct with Anthony Hopkins, one of his listeners volunteered the titles of two other Turtel taub movies: the romantic comedy While You Were Sleeping and Cool Runnings, about the Jamaican bobsled team. When Ralph mentioned that Michael Bay, who had graduated from Wes a year later, had directed The Rock, the same student instructed Ralph that Bay was also the director of Bad Boys. Like a game show host raising the stakes, Ralph next announced that Miguel Arteta was also a Wesleyan graduate, class of'89. Ralph then paused, daring his listener to fill in the CV. Rising to the challenge, the same senior said he knew that Arteta had spent four years raising money to make an obscure movie called Star Maps, about a boy pressed into prostitution by his father.

This kid is not messing around, Ralph thought. The film buff's name was Migizi Pensoneau. With all the talk about Hollywood, Ralph thought that Migizis chiseled jaw was reminiscent of that of a young Val Kilmer. And Migizis penetrating squint and his thick brown hair, which he had clipped short on the sides but left wavy on top, were vintage James Dean. But Migizi—who pronounced his name MIH-gih-zee and preferred to be called Mig—had always been more interested in writing or directing a film than acting in one.

Migizi, whose name means "bald eagle," had come to NAPS a year earlier, at age 17. Like many of the classmates Mig would meet at NAPS, his life had been in free fall. At the public high school he had attended in Bemidji, Minnesota, a small town about four hours north of Minneapolis, Mig had a C average in his freshman year. He had a C average in his sophomore and junior years, as well. One of the only As he received—in a language class taught in his mother's native tongue—had been negated by D's in social studies, biology and geography. He also had two D's, in psychology and philosophy, as a junior. "You're not going to go where you want to go with grades like this,"' his mother, Renee, a professor of Native American studies at a local tribal college, warned him. (Mig's parents had split up when he was young, and his biological father was often away for months at a time until Mig reached his teens.)

Mig had always assumed he would go to college, but fate seemed to be taking him in another direction. Though he didn't drink yet, Mig feared he was on the road to alcoholism, for he didn't have far to look to find relatives and friends whose lives had been decimated by alcohol. What was more frustrating—for Mig, as well as for his mother and his teachers—was that he was obviously bright, and he comprehended everything that he was taught. He just couldn't be bothered to spit it back on a test or in an essay. "I could get a solid A if it was something I was interested in," he said. "But if I wasn't interested, I just blew it off. If I understood the material, I guess I felt I didn't have to prove it."

Mig had certainly proved that he could discipline himself, when he chose to. He had become a black belt in tae kwon do and a teacher of that Korean martial art, and had also worked hard to attain the spiritual concentration necessary to become a pipe carrier within his tribe, the Ojibwa, a religious designation he earned before reaching his teens. Still, he remained bored and aimless in school.

Mig's mothers first attempt at an intervention had come during the fall of Migs sophomore year, after he received a particularly bad round of grades. She forced him to quit his job at Burger King, the phone in his room was disconnected, he wasn't permitted to watch television and he was only allowed to travel to and from school. For a few weeks, his grades improved. But they ultimately slid. "It didn't have the desired effect," Mig said.

One night in Mig's junior year, his mother tried a more radical approach. She tossed him an application to NAPS. "My mom knew I was better than what I was doing," Mig said. "She thought I was in the wrong environment for myself." In late January 1998, Mig sat down and filled out the NAPS application, having finally concluded his mother was right: He needed help. And he had come to regret how much pain he had caused her with his indifference to his school work. But as he answered the questions, Mig made no attempt to conceal his sense of humor, which he had always mined in situations that made him anxious.

For example, when Mig was asked on the NAPS application, "What subjects did you like best and why?" Mig wrote, "Math, algebra," before adding, "Learn something new every day." But he grew serious in one of the essays he submitted, in which he was asked, "What would be the best thing to happen to you this year, and why?" He responded that, "The best thing that could happen to me is to get in to your school." He then sought to describe a slice of his life in Bemidji:

"A lot of the Natives are into drugs and alcohol. Many claim to be in gangs as well. This annoys me because it sends out a false message to other ethnic communities here. These other communities don't see Natives for the beautifully, culturally rich people we are.

"I believe that leaving this town would signal a new beginning in my life. I feel like this school, this town and these people are holding me back from something grand. Something that I can't find here. I feel that your school will help me find whatever it is that I know I must find."

THE ADMISSIONS OFFICER AT NAPS, CHRISTOPHER JOHNSON,

read Mig's application and transcript, and thought he recognized the boy staring back from the page. "I was a gifted kid who no one paid real attention to," Christopher, who is Saginaw Chippewa, said later. "Learning wasn't really interesting to me." Christopher believed that Migwas exactly the kind of kid that NAPS had been created to help. Moreover, Mig's standardized test scores buttressed Mig's mother's contention that he had untapped potential. On the independent school entrance exam, known as the E.R.8., Mig had scored in the 77th percentile for his verbal ability and the 50th percentile for mathematics achievement. Those scores, however low nationally, ranked him near the top of the 200 or so students who were seeking the 15 openings in the class.

And so it was decided that Mig would be offered admission to NAPS. The only catch, Christopher explained to Mig, was that he would have to repeat his junior year. Mig agreed to do so without hesitation. And because Mig's mother's income was low—a single mother, she still had Mig's younger sister at home—NAPS agreed to subsidize much of the $24,000 annual tuition. Mig was in good company. Almost every student at NAPS received some financial aid.

Soon after he got to NAPS, in the fall of 1998, Mig began to thrive. For the first time, he said, he felt ready to pay back the investment that so many people had made in him. He devoured the stories of William Faulkner and Tim O'Brien, and the novel LoveMedicine by Louise Erdrich '76. He pulled his G.P.A. up to a B-plus/A-minus, with As in English, geometry and Spanish. He ran for student council president and won.

When he took the SAT, he scored a 650 on the verbal portion of the exam, and a 560 on the math. His combined score of 1210, while below the average of Wesleyan and many other top colleges, was well above the national average of 1020, according to the College Board, which administers the test. More important, his scores placed him at or above all but 10 percent of the Native Americans who took the test that year.

When it came time to apply to college, Mig relied heavily on teachers and counselors at NAPS. One counselor suggested Beloit in Wisconsin, because of its strong writing program. And so he decided he would apply there. An admissions officer from Pitzer in California had visited NAPS earlier in the fall. The visit left "no lasting impression" on Mig, but he figured there was no harm in applying. And then a counselor had suggested Wesleyan, because of its focus on writing and film. And as luck would have it, Mig was told, an admissions officer from Wesleyan had asked to visit NAPS.

"Hey dude, nice suit!" was how Mig chose to greet the man who had come to talk to him about where he might go to college. This is rural New Mexico, Mig thought, can't the guy loosen up? A crack like that would have probably ended a lot of admissions interviews before they had even begun. No college guidebook would have advised Mig to open such an important interview with what could have been perceived as an insult. But Mig's decision that he would be himself, and let the chips fall where they may had already paid a dividend. Ralph smiled.

But Ralph became more somber when he told Mig that he knew of no other Native American student at Wesleyan. If Mig applied and was accepted, and if he chose to matriculate, he would be a pioneer. No one else at Wesleyan would know what it meant to be a pipe carrier. And no one would be craving the same Native foods as he.

"It won't be easy," Ralph said. "But it will be a real good experience."

Ralph also told Mig that while Wesleyan couldn't offer him a mentor who was Native American, it could expose him to a range of diversity that rivaled that of any other American college. "You will be in an atmosphere open to cultural differences and cultural experiences," Ralph said.

Mig shook Ralph's hand and promised he'd think over what Ralph had said, though he was too shy to pose the question that most concerned him: Did Ralph think he actually could get in? Had Mig asked, Ralph would have explained that he didn't know the answer. These things were not up to Ralph alone. Far from it, he had eight other colleagues. And Ralph could already predict that with a record as checkered and complicated as Mig's, every other admissions officer at Wesleyan was going to want to weigh in on his case before the group arrived at a verdict.

LIKE OTHER COLLEGES, INCLUDING

Dartmouth, Wesleyan sought to insure that at least two admissions officers read each application, with each reader casting a preliminary vote. Two of the possible recommendations were fairly straightforward: "admit" or "deny." Two others were more hedged: "admit minus" meant that the admissions officer thought that the candidate perhaps merited acceptance, though it was hardly a slam dunk; "deny plus" was a similar rating for someone who was likely to be rejected, barring some other quality or talent—such as expertise on the bassoon or with a baseball—that Wesleyan needed in the community it was assembling. If the two admissions officers who read the file agreed that an applicant should be admitted or rejected, the dean of admissions, Nancy Meislahn, and her deputy, Greg Pyke, would usually assent. But in cases where the recommendation was split or muddied, the two senior officials would make the decision themselves or defer to the full committee, which met for a week in the spring to consider the 400 or so toughest cases, after no more than five minutes' debate on each.

On the eve of those hearings in the spring of 2000, Nancy and Greg met inside Nancys small office, in what was formerly the master bedroom of a Dutch colonial home near campus that Wesleyan had acquired a few years earlier. Given the time pressure, Nancy and Greg wanted to make sure at this late date that the applicants they considered first were those who were most likely to be admitted. Thus, the piles of applications around them were arranged to reflect the recommendations of the two previous readers. If one reader had recommended "deny," and another "deny plus," that card went in a pile that was not likely to be read until the end. The likelihood that Nancy or Greg would find reason to admit those applicants was considered slim. On the other hand, Nancy and Greg had made it a priority to work through the pile of those applications in which one officer had recommended "admit" and another "admit minus." These applicants still had a shot.

As Nancy and Greg reached for the "admit/admit minus" pile on that afternoon, the application on the very top belonged to Mig.

As it turned out, Nancy had been the first admissions officer to read the file, only two days earlier. Though much of her time was taken up endorsing or mediating the choices of her colleagues, Nancy had also been reading applications at random, both to give her colleagues a break and to get a feel for this year's pool. Ralph had read the file next, because New Mexico was part of his territory. In this case, Greg alone would be charged with deciding the next step for Mig.

In considering Mig's application, Greg saw that Nancy began her notes by highlighting Mig's most glaring weakness: the mostly C's and D's that he earned at his old high school. But Nancy had also noted that Mig had gotten mostly As at his new school, having repeated his junior year. As the first reader, she was responsible for listing the details of Mig's case before taking a position. After documenting his extracurricular activities—the four years of tae kwon do, his work with the student council and the drama club—she came to Mig's first essay, in which he was asked to describe his most meaningful activity. His choice was a 6o-hour-a-week construction job, which Mig had taken during the summer after his first year at NAPS. Mig wrote, in part:

"I made eight dollars and fifty cents an hour. I got tan. I got buff. My pocket got fat. I'd work with my shirt off and girls would whistle. They'd stop and I'd get their numbers. I got a raise right away. Nine bucks an hour. I didn't think I had earned it, so, to compensate, I worked harder and harder everyday. The tan turned to sunburn."

MIG HAD ALWAYS RELISHED BEING

irreverent in formal situations, and because he had believed that his sense of humor clicked with Ralphs, at least in their meeting at Mig's school, he had decided to write his response to Wesleyan's first question with Ralph in mind. Mig had never stopped to think that someone else might read his words, not least the new dean of admissions. Nancys response was direct. "Immature language," she wrote in her notes, "i.e., 'l'd work w/my shirt off and girls would whistle!'"

Greg, still reviewing Nancys notes, saw that Nancy had next turned to the second essay, in which Mig had been asked to write about a subject of his choice. This time, Mig titled his missive: "My Future Depends on This Essay." Here we go again, Nancy thought, at least at first. But Mig quickly grew serious. Mig had decided to write about his biological father, who lived elsewhere and only called a couple of times a year, at least when Mig was in elementary school. Mig wrote to the committee that he had half-imagined that his father was the "President of Uruguay," but he knew from his mother that his father was battling demons. Mig said he wanted Wesleyan to know about an overnight visit that he and his father had made to Mig's grandfather's home when Mig was 10. Mig wrote:

"I remember seeing my grandpa sitting in his rocking chair. That's how I'll always re lemberhim: smiling at me with a few teeth, and picking me up. He sat my 10- year-old ass on his lap and said to me (I swear this is the first thing he said): 'Have you ever seen Spartacus?' "'What?' " 'Have you ever seen Spartacus?' "'No.' "'This is the widescreen version. You should watch it.' "'When was it made?' " 'Before you were born.' " 'Sounds boring.' (Ten-year-old logic.)

"He laughed and replied with a smile, 'You'll like it. Try it. Watch it.' So I did. It's the first time I really remember taking in a movie. I watched it for the first time, as if it were the last. The whole time, Grandpa and my dad explained things to me. 'They were slaves then, Migizi Poems were called songs then, son Cruci-fix ion was the way people were punished by the rulers of the time....' So I watched the movie in all its epic splendor: vibrant colors, beautiful scenery, wonderful direction, good.story. It's still one of my favorite movies."

Mig reported that he had left his grandfathers home elated, but his good feelings would not last. When Mig and his dad returned to their hotel room, his father "showered, shaved and left for the night." He had a date, and Mig, at age 10, was left alone with the television. A few years later, Mig's grandfather died. Mig concluded his essay:

"When my grandpa passed on, my dad lost something in himself. At the same time, however, he gained something. He calls more. He keeps in touch. He sends me news of the weird from the Star Tribune, and Uruguayan money (just kidding.) And! We always watch movies together."

Again, Nancys response was unequivocal: "V. interesting! Anecdotal-style relation ship w/father—a bit cynical, but clever." She was clearly starting to like this guy. Mig gained even more ground when Nancy came to the evaluations of his current teachers. They described the "dismal learning environment" at Mig's old school and then observed how Mig had found his "voice" and "natural ability" at NAPS. On the line in which she was asked to summarize Mig, Nancy wrote: "Intriguing! NAPS has done wonders for him! Solid scores and promising perf. at NAPS ++."

Still, Nancy had two nagging questions about Mig. She wrote that she wasn't sure that Wesleyan "would be a good place" for Mig. And she wanted to see his mid-year grades, just to confirm he had not reverted to prior form. And so Nancy circled "admit minus"—admit, but with reservations—as her recommendation, and wrote the word "committee" next to her vote. She wanted her colleagues to make the call on this one.

Greg, functioning as Nancy's backup in this case, would be the one to decide whether Mig indeed went before the committee. As he continued the review of the summary of Mig's file, Greg saw that Ralph's evaluation had been more emphatic. Greg knew how hard Ralph had been trying to recruit a Native American to Wesleyan, for the first time in recent memory, and Ralph's brief notes indicated how strongly he felt that Mig was the guy. 'A real intriguing young man," Ralph wrote. Absolutely devoted to film. Determined and capable. Not great academic case but in credible person." Ralph had closed with another term that would be instantly recognizable to his colleagues—"Would add," Ralph wrote, meaning Mig would add much to Wesleyan—before circling his choice: Admit."

But after taking one lo'ok at those C's and D s from Mig's first high school, Greg was sure that Nancy was right: This one should go before the committee.

Nearly two weeks later, during the last of the committees five all-day hearings, Mig's case came to the floor. Nancy, serving as the chair, first read her notes aloud to the committee, and then Ralphs. Before the discussion even began, Ralph wanted to answer one of Nancys questions immediately. It seemed that Mig's grades during the fall of senior year had dipped from his junior year, but only slightly. Reading from apiece of yellow legal paper covered in green ink, Ralph told the committee that Mig had C's in honors precal culus and physics, but a B in Spanish and A's in English and civics. Mig was still far ahead of where he had been in Minnesota, Ralph said.

Ralph knew what the next question from the floor would be. Before considering Mig's case, the committee had also debated the application of one of Mig's 14 classmates at NAPS, a far better student four As and a B in his senior year—with an impressive 700 on the verbal portion of the SAT. (The median verbal score in the incoming Wesleyan class so far was about 700.) The committee had wasted little time in voting to take him. Now, they wondered, why should they put themselves out on a limb to take Mig, who appeared so inferior to his classmate, at least on paper?

"There's no doubt about it," Ralph said, confirming that Mig's classmate was "a stronger student." He went on: "There's some risk here with Mig. But Mig's someone who has had a back-ground harsher than anything we typically see." After talking about how Mig had lost friends and relatives to alcoholism, and been surrounded by so much hopelessness in his high school, Ralph said: "In surviving this far, he's come farther than most of our students will, in terms of personal strength—in terms of literally being alive."

Now Greg had a question for Ralph: "How likely is it these kids are going to come?" He was genuinely curious, but he also wanted to know whether Wesleyan, if it accepted both Mig and his classmate, would be throwing away two acceptances. A few weeks earlier, Ralph told Greg, he had spoken with the school's guidance counselor. It was an off-the-record chat in which the counselor told Ralph that Mig really wants to come" and was eager to be a part of the vaunted Wesleyan film program. Someone else asked Ralph how Mig had reacted to the prospect of being the sole Native American on campus.

"I was very straightforward with him," Ralph replied. "I told Mig that Wesleyan could be a supportive place, but that he would be part of a beginning effort." Ralph sensed that his colleagues weren't buying it. There was immediately talk of taking the classmate, and not Mig. Wesleyan was always reluctant to admit someone with Cs and D's, not only because of the risk that he might flunk out but also because of the message it might send to his school, and others, about the grades that Wesleyan considered acceptable.

And what about NAPS itself? The school had only been in business for four years, and had just graduated its first class the year before. Several committee members wondered how much value to attach to Migs As and B's there. There was noway to know for sure.

"Ready to vote?" Nancy finally asked. Ralph and his colleages nodded that they were. The majority would decide. 'Admit?" she asked. Ralph lifted his hand high. As he looked around, he saw that six others had joined him. "Waitlist?" There were no hands. "Deny?" Two hands. By a vote of 7 to 2, Migizi Pensoneau would be offered admission to the class of 2004 at Wesleyan University.

Because EVERY APPLICATION WAS READ BY AT LEAST TWO OFFICERS, EACH OFFICER WAS RESPONSIBLE FOR DEALING WITH NEARLY 1,500 APPLICATIONS MOSTLY IN THE EIGHT WEEKS BETWEEN EARLY JANUARY AND EARLY MARCH.

The ad missions OFFICER CIRCLED "ADMIT MINUS"—ADMIT, BUT WITH RESERVATIONS—AND WROTE THE WORD "COMMITTEE" NEXTTO HER VOTE. SHE WANTED HER COLLEAGUES TO MAKE THE CALL ON THIS ONE

Jacques Steinberg is a national education reporter for The New York Ti mes. A former ed-itor in chief of The Dartmouth (from 1987 to1988), he now lives in Manhattan with his wifeand two children.From The Gatekeepers by Jacques Steinberg.Copyright © Jacques Steinberg, 2002. Used byarrangement with Viking Penguin, a member ofPenguin Putnam Inc. To purchase the book, goto www.the-gatekeepers.com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

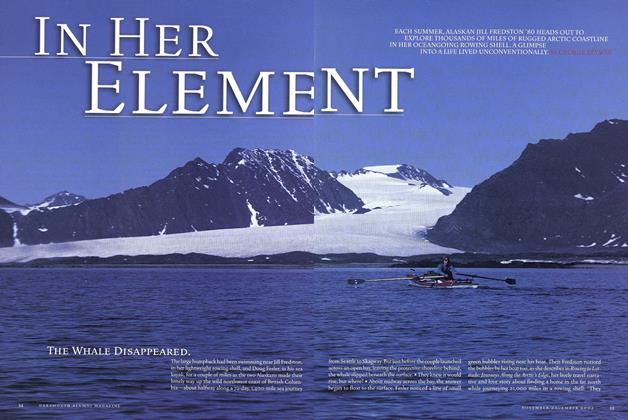

FeatureIn Her Element

November | December 2002 By GEORGE BRYSON -

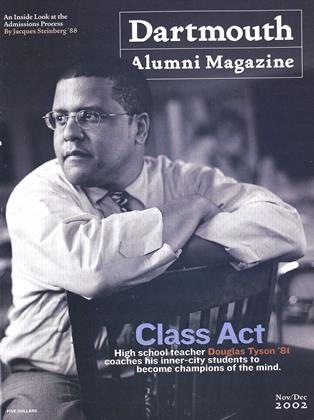

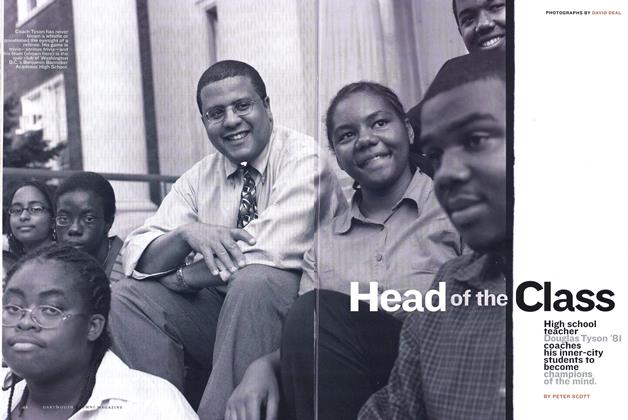

Cover Story

Cover StoryHead of the Class

November | December 2002 By PETER SCOTT -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Iraq Question

November | December 2002 By Daryl G. Press -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

November | December 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Outside

OutsideThe Literature of the Logbooks

November | December 2002 By Madeleine Eno -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

November | December 2002

JACQUES STEINBERG ’88

-

Feature

FeatureLive From New York!

MAY 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdH. Carl McCall ’58

Sept/Oct 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdJohn Hagelin ’76

Mar/Apr 2001 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

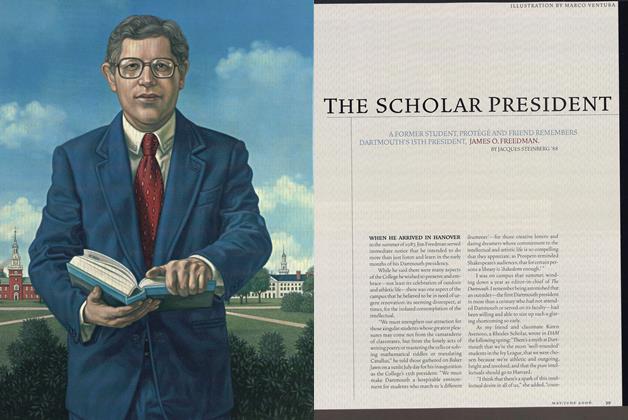

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

May/June 2006 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

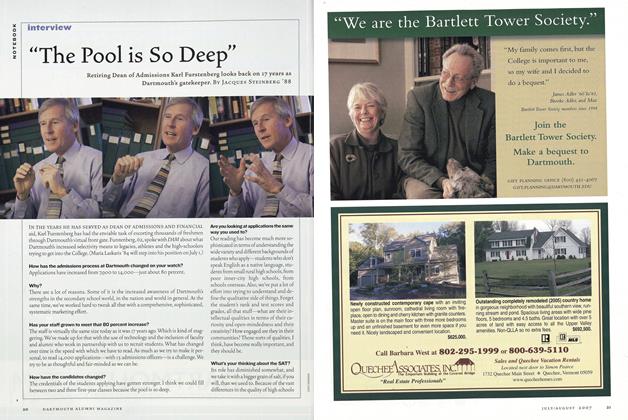

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“The Pool is So Deep”

July/August 2007 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

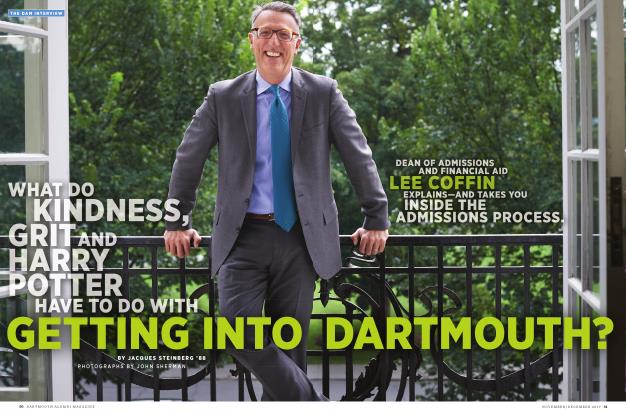

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWLee Coffin

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureOpportunities for the Coming Year

NOVEMBER 1970 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1972 -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BECOME A LAWYER

Sept/Oct 2001 By DANIEL WEBSTER -

Feature

FeatureOrozco And I

MARCH 1991 By Theodore Wachs Jr. '41 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCarl Wallin Bary Harwick '77 Ellen O'Neil '87 Sandy Ford-Centonze

OCTOBER 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96