Scientists come up with the darndest facts. For instance, three years ago Prof. Charles J. Lyon of the Botany Department demonstrated that strange things would happen to plants grown under gravity-free conditions. Twenty years ago the findings would have been noted in botany journals and ignored by virtually everyone else. Today, with man poised to blast off into interplanetary space, it is a fact of considerable moment.

Under the weightless conditions of prolonged space travel a renewable oxygen supply would be needed. On Earth plants exchange carbon dioxide and oxygen with men and animals to maintain nature's balance. Some such exchange would be needed in space because oxygen tanks big enough to supply astronauts for long periods would be too heavy. Plants seemed to provide one logical answer.

But Professor Lyon showed that without gravity plants become twisted. Their leaves and branches fold back around the stem, overlap, and curl. In this condition they would be poor suppliers of oxygen or anything else. He also found out why. A plant's normal upright posture and the precise arrangement of its stem, branches and leaves are maintained by the combined action of gravity and certain plant hormones called auxins. Nature regulates plant growth by transporting more of these hormones to the upper side of the branches. Gravity balances the situation by drawing the excess to the lower side so that growth proceeds evenly. With gravity counteracted, the balance is disrupted. Growth on the lower side lags while that of the upper side speeds up in response to the excess auxin and this curls the branches and leaves down and around.

With its responsibilities for putting men on Mars or Venus or somewhere else in the future, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration took note. They wanted to know more and awarded Professor Lyon a $50,000 grant to continue the studies. Perhaps he could find a way to counteract the twisting so that plants could supply oxygen and even be a minor source of food in manned space travel.

The preliminary findings are encouraging. Professor Lyon believes that certain chemicals, applied at certain places on the plants at the proper times and in the proper concentrations may provide an answer. But sometimes an advance in knowledge also poses new problems.

"We don't yet know what species will prove most efficient as a producer of oxygen on long space flights," he said, "but the odds favor the fast-growing herbaceous annuals which must be started afresh from seeds as each crop reaches the end of its vegetative phase." But germinating seeds appear to be strongly affected by even slight vibrations such as might be experienced in space craft. Sometimes the roots grown "up" out of the soil instead of "down" into it. These effects might be even harder to eliminate, he says.

Basic science no longer needs anyone to make a case for its importance. But once again it's good to remember that efforts to conquer nature begin with efforts to understand it. Professor Lyon began with experiments in how plants transport a growth hormone and now they are of international significance in plans for traveling beyond man's natural environment.

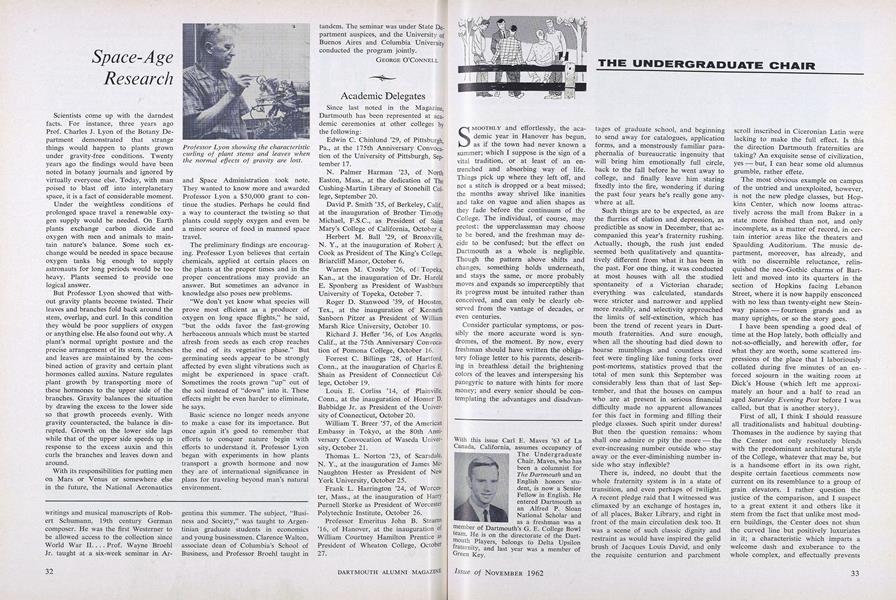

Professor Lyon showing the characteristiccurling of plant stems and leaves whenthe normal effects of gravity are lost.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue