Part III (1915-1963) in a three-part series

SINCE the early 1900's most of the new songs of Dartmouth had been of the "athletic" type. This was disturbing to some of the older alumni. Harry Wellman made this assertion in the November 1912 issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE: "Dartmouth songs of late have been pretty feeble productions, football yawps for the most part, with 'green' and 'team' forced into unwilling matrimony of rhyme, obliged eternally to consort with 'might,' 'fight,' 'cheer,' and 'dear' - bumpily bounding to the clash of cymbals and the booming of an ardent drum. One might think that Dartmouth life consisted of a perennial football contest; for our youngsters have struck no other note. What is needed is a good campus song or a fireside song, something that will express the finer sentiment of the undergraduate toward the old College, and will serve to touch the alumnus with the recollection of his own far, fair days among the hills. Hovey didn't exhaust the subject by any means; some of the deeper experiences of college life he never reached for in his poetry."

With this same thought in mind, Weld A. Rollins '97 had offered a $100 prize in 1910 for the best Dartmouth song written by an undergraduate. During the first year after this offer there were two claimants, but in the opinion of the judging committee neither was worthy of the prize. The next year no songs at all were offered.

The competition was then modified so that only the music need be original, with the suggestion that Hovey words might be used. It was specified that entries should be in the hands of H.R. Wellman on or before November 30, 1912. Associated with him on the judging committee were E.K. Woodworth '97 and Homer E. Keyes '00. Still nothing happened.

In the spring of 1913 the competition was reopened, and the committee changed to include Nelson P. Brown '99 and to omit Harry Wellman. Weld Rollins wrote the ALUMNI MAGAZINE at that time: "For the past three years I have offered a prize for an undergraduate song which might have its premiere at annual dinners of various alumni associations. Last year five more hopefuls registered their creations with the committee. Still none came in with sufficient merit. So, I will change the conditions again. The competition is extended to include not only undergrads but also graduates, non-graduates or any members of the families of the above who have a sufficient connection with the College." Another closing date was set, December 1, 1913.

Search of the archives fails to reveal that even with the easing of the rules any further entries were received.

While all this struggle for new material was in progress the third edition of the Song Book appeared in 1914. There were' three new numbers, and two had been removed. Otherwise the edition was practically a reprint, to keep up with the everrecurring campus demand which arose each fall with the matriculation of freshmen. The Song Book was a "must" for the neophyte, along with a Dartmouth banner, a Dining Association meal ticket, a John Spaghett statuette, a framed picture of September Morn, a "Mem" book, and a pressing ticket. If you went all out, you also subscribed to The Dartmouth, the Bema, the Green Book - and joined the Outing Club. And if you were really gullible, you bought a seat in Chapel from the big guy in the green sweater with a big block D on it.

Two of the new numbers were sensational, and have previously been commented upon—the "Touchdown Song" and "Dartmouth's in Town Again." The third, "When the Green Comes Forth to Battle," by R.L. Sisson Jr. '14 and R.L. Wilkinson '14, was also introduced. This must have been given a cool reception because it never appeared in subsequent printings.

It is unfortunate that this pair of classmates left so little for Dartmouth posterity, because they both had talents which, properly encouraged and fostered, could have produced songs of outstanding value.

Wilkinson was already widely known as a composer, and his operettas, comic operas, and librettos had won him several undergraduate prizes. In 1911 he won a $200 prize for the best original operetta offered in competition that year, and two years later he received another award for a two-act comic opera. The Prom-Commencement show of 1912 ("The Green Parasol") contained lyrics written by Wilkinson and a classmate, James Marriner.

Rufus Sisson, born under the Clarkson influence in Potsdam, N.Y., was likewise a most versatile man. He played freshman tennis and freshman and varsity basketball. On the non-athletic side he was an assiduous member of both the College Choir and the Glee Club, and was likewise active in various prom shows.

NINE years went by. World War I had come and gone, but it had thrown the normal processes of the College into turmoil. The undergraduate body had been almost threatened with extinction in 1917-18, saved only by the November armistice. Later, the returning veterans, advanced in age and maturity, found little in common with the adolescents arriving from the secondary schools. It was several years before campus life resumed its natural pattern. It was time for another review of the Song Book situation.

The 1923 edition of the Song Book came about after a long exchange of correspondence between Harry Wellman and Edwin Grover. Wellman had returned to Hanover in 1919 to join the Tuck School faculty, with the same verve and ebullience he had displayed on campus as an undergraduate a decade and a half before.

Grover thought the new issue should contain more Hovey lyrics, to which he had rather complete access. Wellman pointed out that this would increase the size and cost of the book but would not increase the size of the market. He felt that only one new song had been written since 1914 that was worthy of inclusion, and that it would not be business-like to pay out additional sums to have more Hovey poems set to music. "The only way to sell a new song is to have it sung, and even if the Hovey lyrics were set to singable tuaes there would still be the question of their favorable introduction to the student body."

Finally, with much editing, which in this case meant cutting, copy for the new book was ready. Some of the older, motheaten numbers were dropped, and Grover was asked to suggest still more deletions. But he still favored the use of some of the Hovey poems which would appear in a new edition of DartmouthLyrics, due for publication in February 1924. Wellman repeated that if the size of the book were increased the selling price might go as high as $2. The undergraduates were already "kicking like steers" at having to pay even $1.25.

Eight months later the debate was still going on. Wellman said that statistics showed that the majority of living alumni was now "this side" of the class of 1908. The numbers that Grover wanted to insert, or keep in the Song Book "might have been of some interest to his [Grover's] group back in 1892, but they have no significance three decades later. Besides, the older groups would not be interested in a new edition because they probably had two or three song books already."

This marketing evaluation was proved correct. The poor sale, and the fact that all the details of copyrights, printings, royalties, and sales were consuming too much of Wellman's time, caused him to suggest in 1928 that he was willing to deed his half of the Song Book interests to Dartmouth, and it was his hope that Grover would do the same.

Thus the way was paved for the entrance of the College into the music publishing business. And this marked the end of the saga involving the song-plugging team of Grover and Wellman. They had been tramping the boards together for over twenty years.

ALTHOUGH the subject has only an off-side connection with Dartmouth songs, it might be interesting to digress at this point to relate a few instances where outside requests for their use have arisen - thus proving the ever-spreading universality and acceptance of the music of Dartmouth.

Editors of songbooks for other colleges, and publishers of general college songbooks, have come in steady procession to ask for permission to use Dartmouth numbers. In 1931 Marshall Bartholomew, the patron saint of the Yale Glee Club, obtained permission to use "Eleazar Wheelock" in a new edition of the Yale Songbook. In 1927 the University of Chicago included "Glory to Dartmouth" and "Men of Dartmouth" in its compilation. Previously Union College had received similar authority. Spring-field College inserted "As the Backs Go Tearing By" in its ditty bag. Bill Cunningham '19 asked for permission to use the same number in a wrestling film built around the "flying tackle." (This was the era of wrestler Gus Sonnenberg '20.) Wellman said, "Okay, you may use it for free - but make sure the movie is a good one."

In 1926 a young lady in New York who shall remain anonymous wrote that she was working on some clog dance numbers to be published the following spring. She wished to use two Dartmouth tunes which she thought would be adaptable, "When the Backs Go Tearing By" and "Dear Old Dartmouth." Harry Well-man replied at once that he didn't believe the authors would permit use of the music for this purpose. The lady hoofer then asked if she might not write directly to the authors, stating "I cannot tell you how discouraged and distraught I am."

Harry Wellman thereupon exploded as follows: "I am sorry to inconvenience you, but the fact of the matter is, I don't care to have my stuff used for clog dancing, and I'm sure the authors feel the same way. Personally, I have no feeling against clog dancing, but it seems to me that there is a very definite type of music that goes with this sort of effort, and it would not help a college song to be so used."

With the advent of radio, talking pictures, and television - and the upsurge of record sales—it became practical to appoint an agent to represent the College in the granting of permissions, the collection of royalties, etc. There had been a ten-year contract with the Thornton W. Allen Company, and then one was signed with the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP). From all reports, this still continues to be a most satisfactory arrangement, even though it lacks the personal pungency which obtained when Harry Wellman was running the show.

The new song that Wellman reported to Grover as being the only one to appear on the horizon between 1910 and 1922 was "Hail Dartmouth." It is a spirited number offering great opportunities for band and orchestra arrangements. Unfortunately, it is not a "close harmony" piece being too vivace or presto, as professional musicians would have it, and there are tricky modulations that tend to trip up the extemporaneous barber-shopper.

When the song was introduced in the fifth edition it ran to 56 wordless bars before breaking into the chorus. Also the first chorus had a clamorous ending including six shouted yells. However, Chester Newcomb '12 deserves high mention for this fine piece of Dartmouth music. It is to be hoped that its popularity will remain undimmed, even though its use may be restricted for the reasons set forth above. Newcomb presented the piece at one of the many testimonial dinners given for President Hopkins during his active tenure at Hanover. The occasion was the alumni banquet at Cleveland in the winter of 1921-22. Its first official use at the College was delayed for a rally on Memorial Field on the afternoon of October 11, 1922.

DURING the reign of Song Books III and IV the search for more material had been continuing. In 1917, C.B. Little '81 of Bismarck, N.D., had made a new $100 offer for a "suitable Dartmouth campus song." Any undergraduate or alumnus was eligible and there was no time limit. There were, however, four restrictions which probably frightened away many potential entrants: (1) It must be a campus song. (2) No song is to be considered which concerns itself with athletic contests, or which is merely a rephrasing of hackneyed expressions of love for the College. (3) The song must constitute a poem of high quality without respect to its musical accompaniment. (4) However, poetic quality without the characteristics of a good song will not entitle the work to consideration.

The judges selected for this prize award were H.E. Keyes '00, Prof. F.P. Emory '87 of the English Department, and Prof. P.G. Clapp, Director of Music.

The music failed again to be awakened.

Then, in mid-January of 1931—long after Judge Little's prize had been offered and the judging committee had disbanded through idleness - a song appeared which burst like a new comet into the crisp winter sky. It would have satisfied every condition that Little had set forth. It immediately won deserved acclaim, and will hardly be equalled again for its smooth-flowing thoughts and phrases. It was "Dartmouth Undying."

Franklin McDuffee '21 was a country boy from Rochester, N.H. His only literary accomplishment in high school had been as editor of the school paper in his junior and senior years. As a college undergraduate he lived unobtrusively in Richardson and later College Hall. He was a member of The Arts, of which he later became president. He was also associate editor of the Bema and winner of the Perkins Prize of $500, as the most promising scholar in English Literature.

A superb student, in spite of his persistent habit of over-cutting classes, he was graduated Phi Beta Kappa, summacum laude. On this basis, and with the high approval of President Hopkins, he was awarded the Richard Crawford Campbell Jr. Fellowship, which permitted him to spend two years at Oxford.

In England, honors began to pile up. At Oxford's annual Encaenia he read his own poetic rendering of Michelangelo, the subject assigned for that year. This brought him the Newdigate Prize which had been established back in 1806. This honor is never awarded except for poems of exceptional merit, and several years would often elapse with no nomination being made.

It was quite natural that upon his return from abroad he should join the Dartmouth faculty. He was continually under the watchful eye of President Hopkins who, knowing better than anyone else of his unusual poetic talent, was urging him to make effective use of it. One of Mr. Hopkins' projects for him was to write a Dartmouth lyric which would be adaptable to a Dartmouth song. Finally, the masterpiece emerged. Franklin's mother tells the story of its intimate debut:

"Well do I recall the first time 'Dartmouth Undying' was ever spoken aloud. The morning Franklin wrote the poem he said to me, 'Mother, I have been repeatedly urged by President Hopkins to write a Dartmouth song. Will you listen a moment to see if you think these words are suitable?'

"When he had finished reading, I said with deep emotion, 'Franklin, you have written a poem which, set to music, will live throughout the ages.' With his innate modesty he replied in disgust, 'Mother, don't be absurd! I hoped you would listen with the ears of the public, not as a doting mother.' 'Franklin,' I said, 'I heard that poem with the spiritual ears of the men of Dartmouth, and I reiterate, 'that poem will live'."

In later years Mrs. McDuffee wrote, "I have often had assurance from men of my own generation as to what the song means to them, but it gives me profound satisfaction to know that the younger generations are likewise being moved by its poignant beauty."

Franklin McDuffee, according to President Hopkins, was a paragon of faultlessness. He would work for days at a writing task, decide the result was not good enough, and destroy it. Because of this combination of modesty, humility, and desire for perfection it is probable that many rough McDuffee diamonds which might now be glistening as polished stones were never permitted to display their brilliance.

As Franklin's accomplishments grew, his self-assurance shrank. He became continually fearful that any new endeavor would be measured and compared with previous successes — and be found wanting. He seemed to feel that having scaled the highest peaks, all else was postlude. One afternoon he paid a call on President Hopkins. He begged him to accept his resignation from the faculty, saying that he could no longer stand sure-footed in the winds of the pinnacle. He wanted to drop down to the quiet serenity of the forests below. He was told again of the high admiration in which he was held by his students, the faculty, and the administration. After a long discussion, Franklin finally promised to delay his ultimate decision until the following day, but his mind was irretrievably made up. He never came back to give the answer to his finest friend.

The Rev. Chester Fisk, at a memorial service for Franklin McDuffee, stated, "To some a measure of immortality is granted before death, and thus it was for this man. The delicacy of the images in which the sights and sounds of Dartmouth are reflected by the music of Professor Whitford's score do not convey the lusty vigor of 'her sharp and misty mornings, the clanging bells, the crunch of feet on snow ... the crowding into commons ... the splendor and the fullness of her days.' But these are forever recorded in the words. The music is more in harmony with the softer phrases of the song, simply stated but graphic in description - 'the long, white afternoons' — 'the twilight glow' - 'the soft September sunsets' - 'those hours that passed like dreams' - 'the long cool shadows floating on the campus, the drifting beauty where the twilight streams'."

President Hopkins was not only the prime mover back of McDuffee's supreme accomplishment, but he also selected the man who was to enshrine it with compatible harmony. It was Homer P. Whitford who was called upon to perform this glorious, satisfying task. He had been a member of the Music Department for eight years as organist and director of the college choir. His glee clubs had won two intercollegiate contests in Carnegie Hall. Although Whitford's forte had never been musical composition, President Hopkins must have had an intuition that he could provide a setting of matching quality. No one can dispute that he did exactly that.

THE personnel of the Music Department for the three decades following the war years was colorful, bringing to Dartmouth much acclaim and strengthening its reputation as a singing college.

The dean of the group was Leonard Beecher McWhood. He was in his late forties when he arrived in Hanover to succeed "Harmony" Morse (1901-18) and Horace Greeley Clapp (1915-18). The Students' Army Training Corps had superseded the "undergraduate body," and one of McWhood's first assignments was to build up the morale of the Corps through mass singing exercises in Webster Hall. The pillars rang with "Tipperary," "There's a Long, Long Trail Awinding," "K-K-K-Katy," Over There, and "Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kitbag." ("Mademoiselle from Armentieres" was omitted for obvious rea- sons.) A few of the members of Companies A, B and C and the Hanover Navy from Sanborn Hall may even now recall the night when the singers completely took over the program from Conductor McWhood, who could only express his feelings at that moment with the brief, immortal words, "How I enjoy your exuberance!"

Little by little, the Music Department increased in size, adding Maurice Long-hurst in 1921, Homer Whitford in 1923, and Donald Cobleigh '23 in 1925. All but Cobleigh were distinguished organists, and that fact probably brought about the jealousies that seem to have arisen within this circle of professional musicians.

Homer Whitford was the first to leave, possibly because he had shorter tenure than Longhurst or McWhood. He resigned in 1935 to assume duties as organist extraordinaire in the relative peace and quiet surroundings of Cambridge, Mass. There he continued as organist for several church parishes, and as director of singing groups in the area.

The most versatile member of the Department was undoubtedly Maurice Frederic Longhurst. He was a red-haired fireball. Within two years he had revived the Handel Society Symphony Orchestra, later to be known as the Hanover Community Orchestra. He inaugurated the Dartmouth College Concert Series. He was responsible for several annual presentations of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas, having previously studied under members of the renowned D'Oyly Carte company. He conducted and assisted in the staging of several Carnival musical shows. He was given the task of supervising the construction and installation of the bells in Baker Library Tower, and provided ingenious devices so that most of the bell music was automated. In his "spare time" he was organist and director of both the junior and senior choirs at St. Thomas Episcopal Church. After 32 years of strenuous service Professor Longhurst retired in 1953, and went to Florida, presumably to unwind. He died in Palm Beach seven years later at the age of 72.

Donald Cobleigh '23 was the youngster of the group. He returned to Hanover two years after graduation to become assistant in music, was made instructor the following year, and assistant professor in 1935. He succeeded Whitford as Glee Club director and, aside from his classroom duties, that was a prime assignment for the next twelve or thirteen years. In 1940 Cobleigh brought Fred Waring to Hanover to lead the Glee Club in their Carnival concert. That same year the Club enjoyed a 3600-mile trans-continental tour which climaxed the season. The spring of 1942 found the Dartmouth group in the National Glee Club finals in New York.

After 22 years of service in the musical dungeon of lower Webster and the equally disconcerting claustrophobic practice room on the top floor of Robinson, Donald Cobleigh left Hanover to be head of the music department at Wilkes College at Wilkes Barre, Pa. Later he removed to the West Coast, becoming associated there with several music publishing and sales houses.

Cobleigh was largely responsible for many of the arrangements used in the last Dartmouth Song Book, and most of the work on this volume was completed when Paul Zeller took over in 1950.

PRESIDENT Hopkins, it has been seen, was more than academically interested in the musical life of the College. Although he disclaims the memory of it, his voice could always be heard in chapel services well above the choir behind him, as he led the student body in the singing of the morning hymn. He fostered Dartmouth's finest songs. He aided in bringing the best in music to Hanover. He recalls the egoism of Harry Wellman who came to his office in 1907 as a sophomore and announced, "I know more about music than anyone else in the whole g-d place." He describes Wellman as a catalyst who inspired many men of his era to express themselves in the musical medium.

George Parmly Day, treasurer of Yale University for many years, made frequent visits to nearby Woodstock, Ver- mont - and always took time out to visit Hanover and "Hoppy," one of his closest friends. He was a remote descendant of the sister of Eleazar Wheelock, which may or may not explain his affection for Dartmouth. One day in 1935 he announced to President Hopkins that he had written a song. "What shall I do with it?" he queried. It was "The Wearers of the Green," to be sung to the well-known Irish tune of approximately the same title. Its words have the sound of affection which only a Dartmouth man might use in expressing his love for the College. Perhaps Day chose this method to unobtrusively become a member of the Dartmouth family. Needless to say, the well-written poem was immediately relayed to the Music Department, and the legal adoption of the piece and its author into Dartmouth's Hall of Musical Fame was duly effected.

Another newcomer to the 1950 Song Book, but which had been 26 years in its full emergence, was the rather nostalgic bit of verse under the title "Oh, the Wind Is on the Mountain." Its author, Wendell P. Stafford, was of old Vermont stock. He traveled about as far as he could in the field of jurisprudence in his native state, and finally advanced to be associate justice of the Superior Court in the District of Columbia. He had been given an honorary degree by Dartmouth in 1901 on the basis of his exploits in the field of poetry, so it should have been no surprise when, as father of a Dartmouth man, Edward Stafford '11, he presented his rhymed gift at the annual dinner of the Dartmouth Club of Washington, D.C., in February 1924.

Nine and a half years later these verses were reprinted in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE with a challenge to its readers to submit a suitable setting for the poem. So, on Dartmouth Night of November 1933 the Glee Club sang the accepted melody written by Philip E. Everett '18.

It is a delightful number, has been used extensively by the Glee Club, and should continue to be a perennial favorite with both formal and informal singing groups.

Edward H. Plumb '29 was another protege of President Hopkins. He was the youngest of three Streator, Ill., brothers - musicians all. Sam Plumb '21 had oom-pahed his way through college on the alto horn; Gordon "Gin" Plumb '22, as a saxophonist, had been a member of the famed Barbary Coast Orchestra; and Ed came along a few years later to become the trio's most professional member. His musical ability was made evident immediately, arousing the President's interest. It was he who induced Huntley Spaulding of the Spaulding swimming pool family to stake Ed to a graduate course in music on the West Coast. Only a short time elapsed before this training began to pay off, and Spaulding was agreeably surprised to have his scholarship loan to Plumb returned in extremely prompt fashion. Ed had crashed the gates at the Walt Disney studios, which had begun to be forerunners in the field of animated cartoons. They were moving rapidly from black and white to full color, and from five minute shorts to full length productions. These required full orchestral treatments, which equalled in lavishness, quality, and cost any which had been provided for the live Hollywood stage extravaganzas that, in turn, were taking the play away from the Broadway musicals. Plumb became the Musical Director for the Walt Disney productions, and was intimately involved in the memorable performances of Dumbo, Snow White, Bambi. and Fantasia. On the side he was also the arranger for such luminaries as Paul Whiteman, lohnny Green, Vincent Lopez, and Rudy Vallee. He was probably at the height of his career when death came, in his fiftieth year.

His contribution to Dartmouth songs was the setting for the "Dartmouth Challenge Song." The words had been supplied anonymously in the spring of 1934, and Plumb had written the music. That fall, on Dartmouth Night, after the piece had been sung by the combined Freshman and Varsity Glee Clubs, it was announced by Prof. James P. Richardson '99, master of ceremonies, that Ernest Martin Hopkins '01 was the author. In an interview with Mr. Hopkins in January 1963, he expressed his general dissatisfaction with his poetic masterpiece, and indicated that it would suit him perfectly if his effort were criticized severely, so that it might be later assigned to limbo. This we refuse unequivocally to do. It should remain blazoned on Dartmouth's musical walls as an unusual accomplishment of a great man, able to display such talent in an avocation far removed from the fields of education and administration. After all, what other college president ever wrote a good football song?

THE last newcomer to the 1950 Song Book was one with unadulterated nautical flavor, with its eligibility based only on the facts that (1) it was good music and (2) it was written in Hanover. We refer to "Take Me Down to the Sea." Despite its musical merit and its campus acceptance as a fine song with which to harmonize, it is not a Dartmouth song, was not written by a Dartmouth man, and in the afteryears will only be classed as a rollicking chantey, vaguely associated with the early Forties when the United States Navy and its training units were part of the Hanover scene.

Among those arriving from other colleges and locales for indoctrination in the intricacies of naval procedures was a mature individual, aged 31, who had previously made his professional mark in the realm of popular music. Robert M. Bilder, Williams '33 and Harvard Law School '36, had previously entered his father's law firm in Newark, N.J., when the armed forces beckoned. As a Navy lieutenant he spent the summer of 1942 in Hanover in advanced training, before assignments to the West Coast and the South Pacific.

In August of that year Bilder wrote the song "Take Me Down to the Sea" for a musical show put on as an antidote for the concentrated strain which military personnel were experiencing as they trained to be officers in the exploding naval program. The show was a hit, and the song was the number one reason for it.

Fred Waring saw its possibilities for his Pennsylvanians, and immediately secured copyrights to it. His use of it during the remainder of the war years made it a great success, but because of its lack of real green color it has never been known to the world outside of Hanover as having any connection with the College.

After the war Bilder decided he "would do what I'd always wanted to do - write music." Subsequently, living in Malibu Beach, California, he wrote the scores for at least three movies, and in 1950 worked on a Broadway musical of unknown name and unreported fame. During the last decade of his life he returned to the practice of law, moved to Florida for reasons of health, and finally succumbed to heart disease in June 1961 at the age of 47.

And so, rather abruptly, we come to the end of our narrative. We have dealt with melodic generations of Dartmouth personages and their contribution to our inheritance of song. If the ascent to our summit has been tortuous at times, with side excursions up cul-de-sacs that led nowhere, it was only to make sure that we did not miss an unexplored glade or an unexpected vista.

There has been no mention of many songs that should receive consideration as true additions to the muster of Dartmouth song-lore. Lying about are partly finished harmonic sketches, roughed-out chorded sculptures and unframed poetic landscapes that will some day emerge and be found worthy of their antecedents.

Inevitably, there will be someone to add new chapters to this chronicle of song. How soon this is done will depend on the seeds of talent that may even now be lying latent under the fertile soil of the Hanover plain. There will be new Hoveys and Wellmans and McDuffees. These will rediscover for us, perhaps in slightly different cadence and verbiage, the hillwinds, the twilight glows, the great white cold - the evening hush. May their march across the campus of memories be as joyous, profound, and harmonic as was the parade of their singing ancestors who started up the valley towards our granite hill and its lone pine two centuries ago.

Chester G. Newcomb '12, who wrote thewords and music for "Hail Dartmouth,"first presented in Cleveland in 1922.

Franklin McDuffee '21, author of thelyrics for the song "Dartmouth Undying."

Homer P. Whitford, who created the music for McDuffee's matchless poetic vision.

Philip E. Everett '18 wrote the music for"Oh, the Wind Is on the Mountain."

Edward H. Plumb '29 (r), who providedmusic for President Hopkins' "ChallengeSong," shown with Leopold Stokowski.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAUTOMATION: Progress vs. Problem

April 1963 By CLYDE E. DANKERT. -

Feature

FeatureSummer Term Close to Count-Down

April 1963 By R.J.B. -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth in the Public Service

April 1963 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

April 1963 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1963 By CARL MAVES '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1963 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, THOMAS B.R. BRYANT

HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Debaters Are Arguing Themselves Into National Renown

March 1962 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

JANUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

FEBRUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fated Morning

FEBRUARY 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

APRIL 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45

Features

-

Feature

Feature4. Men and Women

December 1987 -

Cover Story

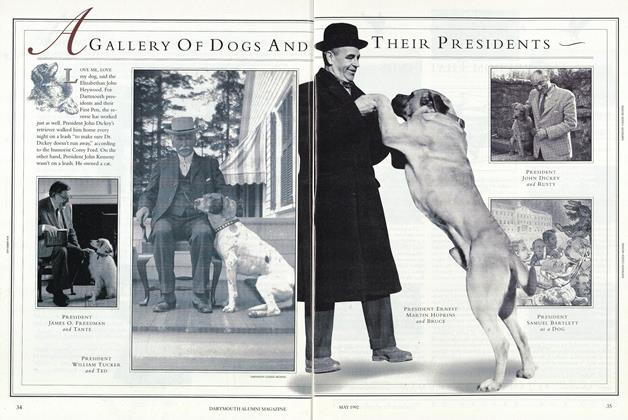

Cover StoryA Gallery Of Dogs And Their Presidents

MAY 1992 -

Feature

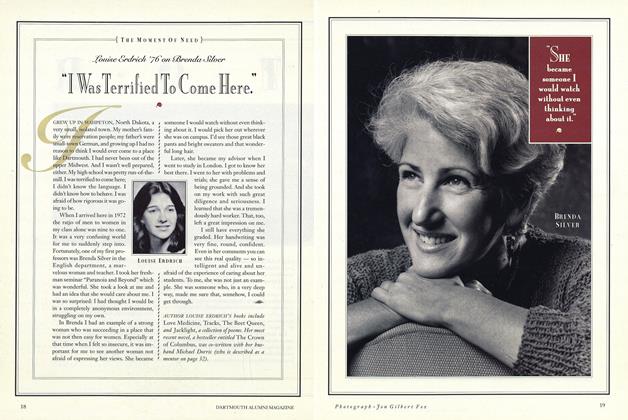

FeatureLouise Erdrich '76 on Brenda Silver

NOVEMBER 1991 By Brenda Silver -

Feature

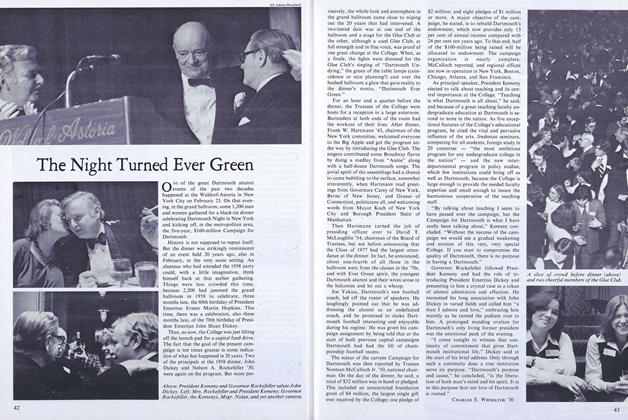

FeatureThe Night Turned Ever Green

APRIL 1978 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

APRIL 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

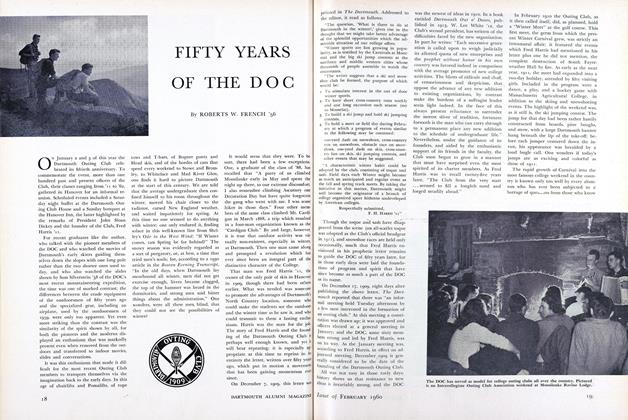

FeatureFIFTY YEARS OF THE DOC

February 1960 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56