Sixty years ago this month the original Dartmouth Hall met a famous, fiery end

At last my fated morning came, And doom of fiery breath;

To the winds of the sky my spirit flew, My body to ashen death.

I live in the hearts of thousands of sons, In story, speech and song, But I'm lonely away from my earthly home; I wait, I wait — how long?

- C. F. Richardson '71

At 7:57 on the morning of February 18, 1904, chapel services had just begun in nineteen-year-old Rollins Chapel. President Tucker had announced the hymn, and Prof. Charles Morse was playing its prelude. Showing unfeigned agitation to a startled monitor, Nelson Fromm '05 was hastily admitted through the south chapel door. He whispered a frightening announcement to Dean C. F. Emerson, who was seated in his usual place close to the entrance. At once, the dean started slowly down the aisle, but quickened his pace to a half-run until he reached the lectern. (The bell in Dartmouth Hall started to strike the hour of eight o'clock.) After a few hasty words to President Tucker, the Dean announced, so that all could hear in the stillness of the moment, that Dartmouth Hall was afire. The President raised his hand to signify the immediate cessation of the service, and bespoke calmness in the sudden emergency. Professor Morse broke off his hymn playing and the entire assemblage bolted for the doors.

From that breathless instant events occurred in rapid succession. While most of the onlookers stood frozen and helplessly aghast, the bell cupola suddenly blazed and shuddered. At 8:23 the 1212-pound Meneely bell plunged through the roof. Later, melted into a misshapen cherry-red lump, it burned its way slowly through the three pine floors and clanked dully into the basement. The belfry spire toppled and followed the bell downward seven minutes later. By 9 o'clock the first main chimney collapsed - and by thirteen minutes to ten there were only twisted, smoldering ruins. In 107 minutes of stunned horror the corporeal body of Old Dartmouth Hall had dropped into its self—made grave.

Dartmouth Hall had stood as the emblem of the College for over eleven decades. Begun in June 1785, it had finally been put into use in 1792. Its fifteen-inch square by 75-foot timbers cut from virgin native pine in the forests of Hartford and Norwich, Vt.; sheathed and floored with lumber from Colonel Payne's mill at the outlet of Mascoma Lake; chimneys and fireplaces laid up in bricks from yards in Hanover and Lebanon; ironwork hand-forged by blacksmith Roger Hovey of Hanover Center —it rivalled in architectural simplicity and excellence Nassau Hall at Princeton (1754) and University Hall at Brown (1770).

If Hanover had been closer to the cultural centers of the Atlantic seaboard, the College's architects might have aspired to the ornateness characterized by the state capital of Virginia at Richmond (1788) with its profusion of classical, decorative forms. Instead, Dartmouth Hall was both plain and inexpensive, built at a cost of about £.4500, cash money, plus gifts such as beef, hides, clothing, and rum. Some of the artisans received their pay in merchandise, - a Mr. Holden being given "two quarts of rum about digging cellar."

It was blasphemed by students and faculty alike — being called the "Old Barn" and "Noah's Ark" in the 1840's, termed "a menace" by President Bartlett in 1887, and a "tinder box" by President Tucker a few years later. It was described as having "grown in trouble, and nurtured in adversity, - a hopeless drag on the prosperity of the College." From first to last it was a source of worry and distress, and the load of debt which remained around its towering neck was buried with it at its death.

A small fire in 1798, originating in a fireplace, caused but slight damage. A tornado in 1802 unroofed the south end. There was a long succession of beitry bells, starting with a hundred-pounder in 1780 or 1781, and followed almost every decade by larger ones, which still cracked and went into dissonance. Its clock also suffered adversity and perversity, due partly to its own mannerisms, but occasionally aided and abetted by college pranks. L. B. Richardson points out that the clock was a "mechanism which, for nearly eighty years, set the time with serene disregard for the movements of the heavenly bodies."

However, architectural authority Mathison described the structure as "one of the finest examples of collegiate architecture of the Colonial period - the most interesting and characteristic college building in the United States." President Hopkins cited its "simple dignity and charm." During his plea to the Boston alumni on the second day following the holocaust, President Tucker stated that there were not twenty buildings then standing in the whole country which represented in age, beauty, and wealth of tradition what Dartmouth Hall had typified on the morning of February 18, 1904.

But to return to further details of the fire. The alarm was given within the building by Nelson Fromm, before taking off for Rollins Chapel. Walking across the third-floor hall he had noticed smoke seeping out from underneath the door of Room 7. On opening it he discovered a "large spot of flames" in the center of the sleeping alcove. At about the same time a "citizen of the town" walking by on College Street saw flames issuing from the roof. This personage was none other than John "Jake" Bond, in later years the College's night watchman.

It was a full ten minutes before any serious attempt could be made to extinguish the blaze. The third-floor occupants of the building were busy attempting to save some of their belongings. H. W. Rainie 'O6 had time to grab his cornet and a dress suit case. His losses included all the band music used by the College Band, a horn belonging to some out-of-town party, and a valuable cello. J. W. Knibbs Jr. '05, captain-elect of the football team, got a hose playing in his room and was able to save most of his possessions, except for an $85 cornet, some valuable pictures, and various athletic trophies. The captain of the track team, H. E. (Jake) Smith '06, lost a roomful of trophies. Prof. Richard W. Husband succeeded in penetrating the north wing and rescued some valuable Greek Department inscriptions.

Hose lines were stretched from Fayerweather Hall, but the water pressure was pitifully low, and the water froze almost at the hose nozzles, since the temperature was twenty below zero. The Hanover Volunteer Fire Department did not arrive until the entire center section had been gutted, and thereafter spent much of its efforts in hosing down Reed and Thornton Halls, which were seriously threatened. At 9:25 fire fighters from Lebanon showed up - but there was little left for them to do.

There was, of course, speculation as to the cause of the tragedy, but evidence appears to be conclusive that it was caused by defective wiring in the floor. Professor Lord observed ironically that "having been preserved from the danger from fireplaces, stoves and wood-burning furnaces, from candles, camphine, whaleoil and kerosene lamps, and illuminating gas, it was finally destroyed by electric wiring." This had been installed in 1892, and later tied in with the College's new power plant.

The sequel to our story started immediately, with the figurative lighting of a flaring and fervid torch that has glowed ever since in the hearts and souls of Dartmouth men everywhere. It was kindled in the first drive for material aid from the alumni of the College that could ever have been termed successful.

The embers were still smoldering on the east campus when, forty minutes after hearing of the fire, Melvin O. Adams '71 engaged Lorimer Hall in Tremont Temple for a Saturday afternoon mass meeting. He issued a call to all Boston alumni, saying, "This is not an invitation. This is a summons." Prior to the Boston meeting the Trustees of the College met and resolved (1) to take immediate steps to raise funds to reproduce Dartmouth Hall in more permanent form on its former site, and (2) to raise $250,000 for the purpose, through a central committee to be appointed by the President.

At the Saturday rally President Tucker echoed the sentiment of all Dartmouth men by stating, in part, "We have lost our visible connection with the century that gave birth to the College. Dartmouth Hall survived the 19th century and stood without a flaw, continuing to respond to all the urgent and pressing demands of the everyday work of the opening 20th century. It represented to us a wealth of tradition of which we now understand the value. It not only embodied the tradition of the College, but carried with it the traditions of all men who belong to her. .. . You can rebuild Dartmouth Hall, and in a certain measure satisfy your sentiments. You cannot rebuild her and satisfy the work for which she stood. . . . Dartmouth Hall is now a memory, but the spirit which inspired it remains untouched, and will rise to face the future years."

Professor John King Lord, in writing the narrative of the fire in the 1906 Aegis, paid this tribute to Dartmouth Hall:

"On the morning following the fire Dartmouth Hall seemed to tower up into the past; a curious juxtaposition of ideas that placed the past above rather than below the present. It towered into the days of the most romantic history that any institution can have, the days of pioneering, of struggles with the elements and hunger and war and cold; it towered into the past of the days that were, before the country in which we live had come into existence, and it towered through the totals of the magnificence of the lives of its sons."

As early as 1894 President Tucker had asked the alumni to subscribe $50,000 for an Alumni Memorial Hall to serve as a college auditorium. The response was wholly unsatisfactory. Alumni had not, at that juncture, acquired the broad point of view which would lead them to assume responsibility for projects of any magnitude. Besides, the country was in a period of depression at the time. After seven years there were funds sufficient only to lay the foundation of Webster Hall, and at that incomplete point the structure remained for several years. Then "the Fated Morning" came. Suddenly it was realized what had been lost through the razing of Old Dartmouth Hall. It had served as the heart of the institution to every living alumnus. Around it were grouped the remembrances of generations of graduates. The time was ripe for action - an opportunity to test the real sentiment of the graduate body.

An appeal went out straightway for a merger of the subscription which had long been in progress for the Memorial Hall with a plea for a new Dartmouth Hall, plus a dormitory.

Within a few months enough money was in sight to rebuild Dartmouth, and the cornerstone was laid in October 1904 (just eight months after the fire). It was a momentous occasion, enhanced by the presence of the seventh Earl of Dartmouth, the great-great-grandson of the second Earl, for whom the College was named. By June 1906 money was also available for the completion of Webster Hall, which was dedicated in October 1907. A total of $240,000 had been raised and expended for the two projects. It was truly a milestone in the College's history, being the first time that an appeal made solely to graduates had met with an entirely adequate response.

The new Dartmouth Hall was the spit and image of the old, with but few minor variations. It was built of red brick, painted white. Its length was the same, but it had been widened by six feet. The steps at each end were from the old building, and occupied a similar position. The lock at the middle entrance was the original lock, fitted with its original key. The belfry tower was duplicated exactly, rising 82 feet from the ground.

Two window frames, out of the four saved from the fire, were put into place on the first floor, but otherwise the fenestration was changed to conform to the Bulfinch method. This added one more tier of panes to the first floor windows so that a 3-2-1 ratio for the three levels was established, matching the architecture of Reed Hall.

In the rear, the east side, a projection was added to balance the vestibule in front, and the flanking doors were moved one window space toward the center.

However, in all the changes, the building never lost its character. Nothing affected its exterior proportions, its simple but sufficient ornamentation. It was perfectly related to its surroundings. In earlier times it had seemed only the expression of the rugged life out of which it came, and by which it was surrounded. Although in the broadening work of the College it had ceased to be the physical center of activity, it drew onto itself the mantle of sentiment and tradition. The newness of other things about it made it still more venerable. The Past was still within it, and about it still hovered the memories of those who had spent their college years within its walls and shadows, and had gone away — many to worthy lives and notable fame.

No other building exists for Dartmouth men which so links the past with the present. It will continue in its future to stand as a reminder of the sacrifice, faith, and energy of those who in earlier times had made the present possible.

The "lonely wait" bespoken by Professor C. F. Richardson has long since ended.

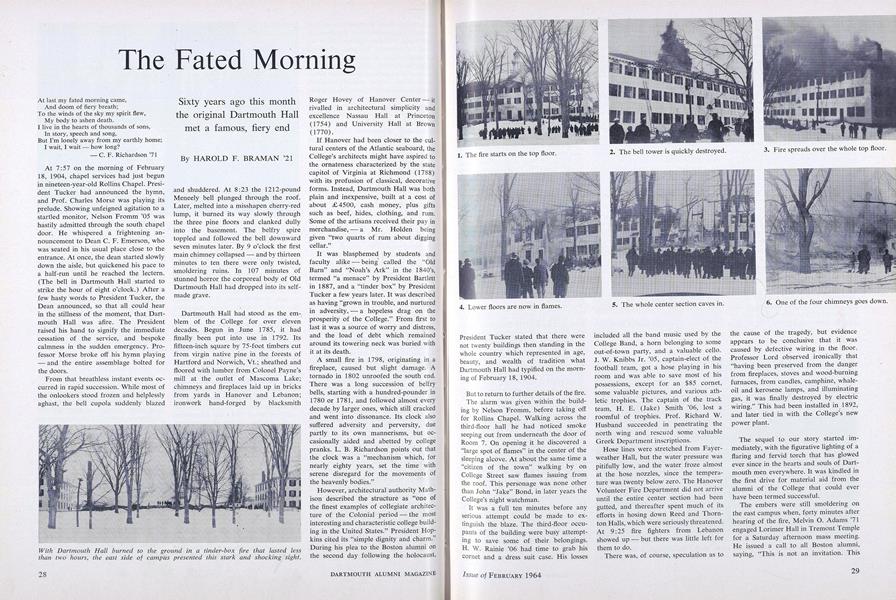

With Dartmouth Hall burned to the ground in a tinder-box fire that lasted lessthan two hours, the east side of campus presented this stark and shocking sight.

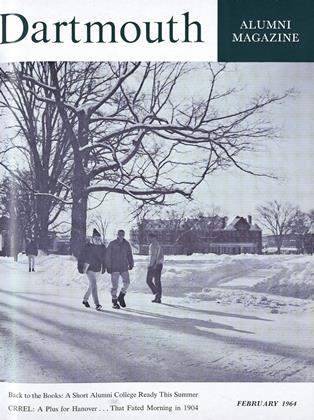

1. The fire starts on the top floor.

2. The bell tower is quickly destroyed.

3. Fire spreads over the whole top floor.

4. Lower floors are now in flames.

5. The whole center section caves in.

6. One of the four chimneys goes down.

One of the most dramatic photographs taken during the fire shows an explosionblasting through the northeast corner and sending spectators scurrying away.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBACK TO THE BOOKS

February 1964 By R.J.B. -

Feature

FeatureThe Cold, Cold World of CRREL

February 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

Feature$44,180,240 and How It Grew

February 1964 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

February 1964 By DAVE BOLDT '63 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1964 By BARRY C. SULLIVAN, E. JAMES STEPHENS JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1964 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER

HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Debaters Are Arguing Themselves Into National Renown

March 1962 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

JANUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

FEBRUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

APRIL 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

APRIL 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45

Features

-

Feature

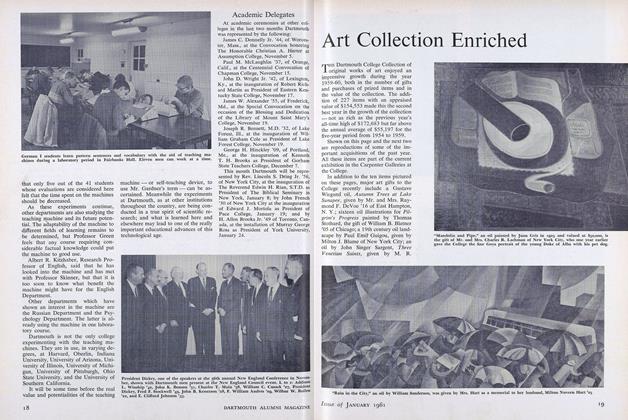

FeatureArt Collection Enriched

January 1961 -

Cover Story

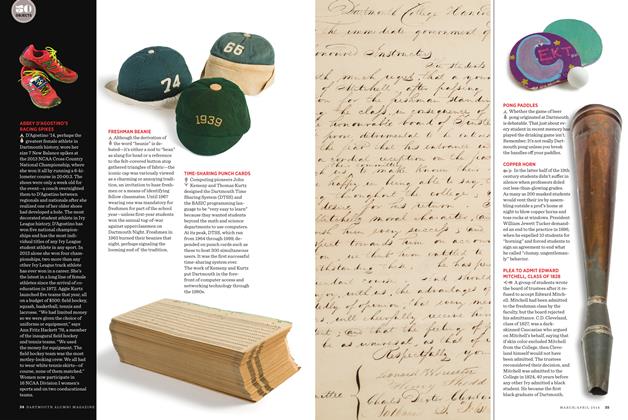

Cover StoryCOPPER HORN

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

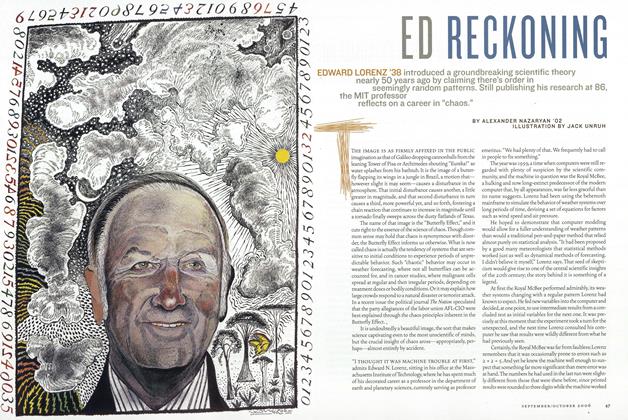

FeatureEd Reckoning

Sept/Oct 2006 By ALEXANDER NAZARYAN ’02 -

FEATURES

FEATURESThe Matchmakers

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

OCTOBER • 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

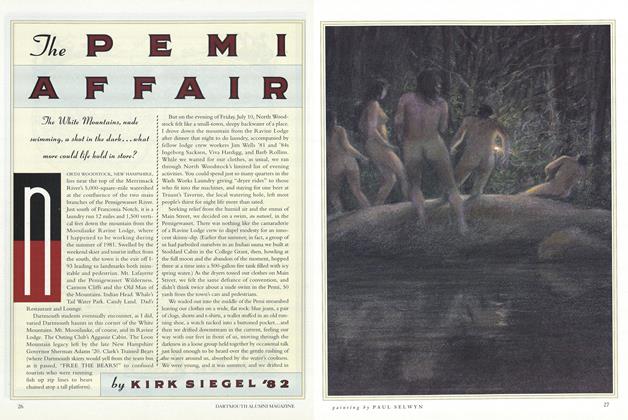

FeatureTHE PEMI AFFAIR

June 1993 By KIRK SIEGEL'82