I SUPPOSE I have always been a conservative of some sort. Sitting in the press gallery at Kemper Auditorium in Kansas City, and watching tanned, articulate Alf Landon address the Republican Convention, I suddenly had almost total recall of the first presidential campaign I was actually aware of - Landon's, in 1936, when he carried Maine and Vermont against FDR. During that campaign, in a bitter Depression year, I wore a brown Landon button. It had a beautiful orange border made of felt, so as to suggest a Kansas sunflower. The Democrats among my classmates in the kindergarten called me an Economic Royalist, a mysterious phrase being bruited about by FDR that year.

Earlier than 1936, I was essentially nonpolitical. Nevertheless, I dimly recall confronting and failing to solve, as an infant, a political problem. My infant mind grasped the fact, no doubt from dinner table conversation, that something called "Hoover" was running the country. The perplexing problem arose from the fact that the family vacuum cleaner was also called "The Hoover," just as one might call a camera "The Kodak." The Hoover resided menacingly in a closet, and periodically it howled down the long and gloomy cor- ridors of our Brooklyn apartment. I now think that I understood, even then, that the vacuum cleaner did not run the country, but further than that my bemused brain failed to penetrate.

The years since my Hoover problem, which must have occurred around 1932, sharpened at least to some degree my political perceptions.

My friend the editor has asked me to comment on my own experience as a conservative in the academic world, certainly an interesting topic, and so I had better begin by specifying just what kind of conservative I am. The conservative breed comes in many gorgeous varieties, more, I am sure, than I can detect among the liberals, a grayer and more predictable group altogether.

About my own conservatism I would like to make three brief points. The first one will be spiritual-aesthetic, the second substantively political, and the third, briefest of all, touching upon foreign policy. In each of these three areas I find myself sharply at odds with many of my academic colleagues.

FIRST, the spiritual-aesthetic. In my own experience, liberalism is relentlessly moralistic, even puritanical. I groan inwardly at a general meeting of the Dartmouth faculty, listening to them moralize away about virtually everything. Liberals are perpetually engaged in a kind of moral Easter-egg hunt, seeking out supposed victims. These victims, hereafter known as Victims, must be rescued from supposed oppressors, whom we will now call Oppressors. In this melodrama, the result is always predictable and therefore boring.

The human emotion of pity is valid, of course, but it cannot be allowed to preempt all other emotions and values. The liberal converts pity into a kind of nervous tic, the habitual response to everything. The liberal seems constantly to be rejecting the spectrum of powerful and valid human emotions that have nothing to do with pity. There really do exist other values in the world than concern for Victims, real or phony. Such potent worldly values include vitality, form, style, beauty in all its modes, heroism, pleasure, freedom, wealth, creativity, and joy. The liberal seems constantly to be repressing or ignoring all of those in favor of a routinized and quickly boring pity.

I recall, a couple of years ago, a moralistic attack from the liberals upon the notion of choosing a Carnival Queen. They charged that the girl was being singled out on the basis of "mere beauty." That language, "mere beauty," just about tells it all. Mere beauty happens to be intensely important to me.

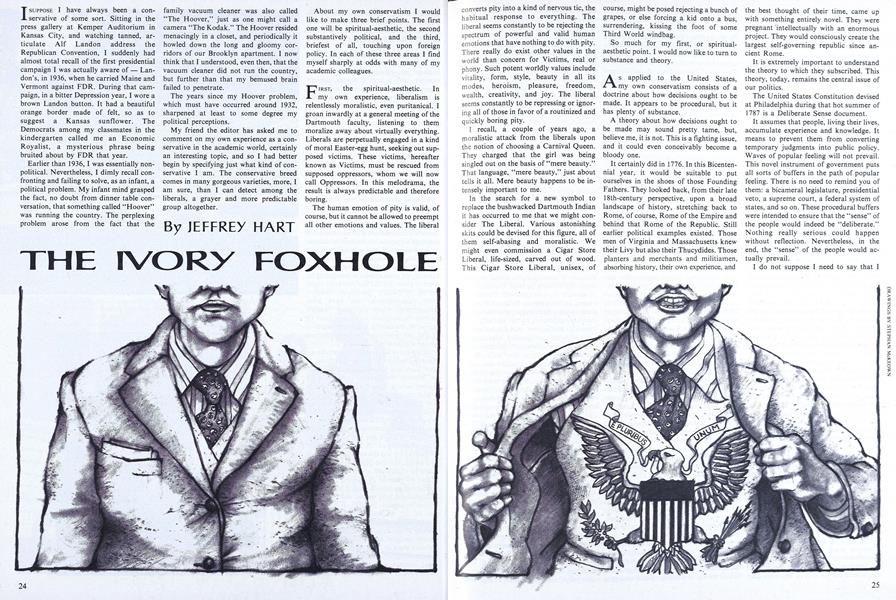

In the search for a new symbol to replace the bushwacked Dartmouth Indian it has occurred to me that we might consider The Liberal. Various astonishing skits could be devised for this figure, all of them self-abasing and moralistic. We might even commission a Cigar Store Liberal, life-sized, carved out of wood. This Cigar Store Liberal, unisex, of course, might be posed rejecting a bunch of grapes, or else forcing a kid onto a bus, surrendering, kissing the foot of some Third World windbag.

So much for my first, or spiritual-aesthetic point. I would now like to turn to substance and theory.

As applied to the United States, my own conservatism consists of a doctrine about how decisions ought to be made. It appears to be procedural, but it has plenty of substance.

A theory about how decisions ought to be made may sound pretty tame, but, believe me, it is not. This is a fighting issue, and it could even conceivably become a bloody one.

It certainly did in 1776. In this Bicentennial year, it would be suitable to put ourselves in the shoes of those Founding Fathers. They looked back, from their late 18th-century perspective, upon a broad landscape of history, stretching back to Rome, of course, Rome of the Empire and behind that Rome of the Republic. Still earlier political examples existed. Those men of Virginia and Massachusetts knew their Livy but also their Thucydides. Those planters and merchants and militiamen, absorbing history, their own experience, and the best thought of their time, came up with something entirely novel. They were pregnant intellectually with an enormous project. They would consciously create the largest self-governing republic since ancient Rome.

It is extremely important to understand the theory to which they subscribed. This theory, today, remains the central issue of our politics.

The United States Constitution devised at Philadelphia during that hot summer of 1787 is a Deliberate Sense document.

It assumes that people, living their lives, accumulate experience and knowledge. It means to prevent them from converting temporary judgments into public policy. Waves of popular feeling will not prevail. This novel instrument of government puts all sorts of buffers in the path of popular feeling. There is no need to remind you of them: a bicameral legislature, presidential veto, a supreme court, a federal system of states, and so on. These procedural buffers were intended to ensure that the "sense" of the people would indeed be "deliberate." Nothing really serious could happen without reflection. Nevertheless, in the end, the "sense" of the people would actually prevail.

I do not suppose I need to say that I revere that theory of government, and also the men who devised it.

Nevertheless, there has grown up in our midst, like a viper in the bosom, an entirely different and contradictory theory. This viper theory appeals not to the deliberate sense of the people, but to theoretical absolutes. It is certainly plausible to discern in this viper theory of theoretical absolutes exactly the kind of thing the men of Massachusetts and Virginia and the other states defeated on the battlefield and rejected at Philadelphia in 1787, in the name of self-government.

The viper theory proposes a government based not upon the deliberate sense of the people, as refined through the careful buffers of the Constitutional mechanism, but upon theoretical absolutes and bureaucratic fiat.

These theoretical absolutes are not found in the plain language of the Constitution, and, indeed, they contradict the "deliberate sense" political theory upon which the Constitution is based. An absolute is an imperative, not the product of deliberation. The theoretical absolutes are discerned first of all in the "created equal" clause of the Declaration — though such a reading of that clause is utterly unhistorical — and they are discerned in the First and Fourteenth amendments, needless to say by tortured interpretation.

My assertions in this regard are neither eccentric nor original. They are completely supported by such specialists as the late Alexander Bickel of Yale, Professor George Carey of Georgetown, and Professor Raoul Berger of Harvard. Berger's forthcoming book on the Fourteenth Amendment, by the way, is going to scandalize liberaldom.

The conflict between "deliberate sense" and "theoretical absolutes" is a profound matter. The people, in their deliberate sense, on the basis of their lived experience, will in my opinion and the opinion of the founders affirm what is true and valuable. That deliberate sense, however, will not effectuate a whole spectrum of liberal projects, both egalitarian and libertine. The deliberate sense tradition, therefore, is being de-railed by a heretical "rights" theory that has no constitutional legitimacy and which is imposing upon the people things that go against the grain of their common sense.

An interpretation of the First Amendment, for example, which legitimizes every excess, which, as Irving Kristol has remarked, says that it is legal for an adult woman to have sexual intercourse on a public stage as long as she is paid the minimum wage, this, I assert, is not government according to the principles of the founders. Americans, I hope, will not continue to put up with it, any more than they long endured a capricious rule from England during the 18th century.

MOST things have an economic aspect, and the liberal exploitation of pity not surprisingly turns out upon closer examination to be a kind of Gold Rush. The rhetoric of liberal idealism justifies and protects those who are currently mining the Pity Klondike.

This enterprise has long been with us, of course, but the really big boom started a little over a decade ago. It gave rise to a virtual "new class" of persons, a postindustrial elite consisting of professionals in education, urban planning, welfare, social research, compensatory programs of all sorts, rehabilitation, poverty law, communications, and similar enterprises.

After Lyndon Johnson's 1964 landslide, the lopsidedly Democratic Congress enacted a cascade of social programs. Education, housing, welfare, and urban outlays soared. Enactment of the War Against Poverty alone brought expenditures of $2 billion a year and rising. As a spin-off effect, it also called into being a hundred firms in the greater Washington area - and of course swarms of others elsewhere - functioning as consultants in the poverty area.

As the federal billions began to flow into the Social Concern sector, private enterprise was quick to sniff out the opportunities. Corporations began to find educational innovation (so called), urban studies, and assorted rehabilitation schemes immensely profitable. We saw the mushrooming of new social-economic entities, what might be called Social Concern Conglomerates. A few years ago, Robert Kruger estimated the social services market as $7 billion per year and growing exponentially. In the Big Bull Social Concern Market of 1965-68, Wall Street investment houses gobbled up securities with names redolent of scientific technology, environmental purification, research, planning, advanced educational techniques, computer software, informational systems, and so on.

Linked on the one hand to a surging social welfare bureaucracy in Washington, and to innumerable related agencies, and on the other to myriad allies in the academy and in the printed and electronic media, this new class has consolidated its political and social power. Of course, it has an immediate and voracious interest in large and increasing federal expenditure. The budget of HEW alone has long since passed that of the Pentagon.

Naturally this new class is ideologically liberal. It is, in fact, in the social change business. Without social problems and social solutions and goals and programs, it would be out of business. Social change is as important to the new class as inventory turnover was to the old mercantile elite, or a good cotton crop to the still earlier planter elite.

Most social change items on our recent and present agenda had their theoretical foundations laid in the academy. They were publicized and sold by the media. The myriad programs and projects occasionally do some good, but generally they do not — and, indeed, recent empirical studies have begun to confirm common sense in this regard. Often, by any reasonable measure, the programs and projects are outright disasters. They include, of course, busing, but also expensive programs of criminal rehabilitation that show no results, elaborate compensatory schemes for the "poor" that do no good, urban renewal and model cities schemes that are counter-productive, affirmative action hiring and "experimental" textbooks that outrage the normal person and so on. Each program sustains thousands of administrators and other professionals. Because so much of this is either useless or actually disastrous, it all has to be sold to us as "moral," "compassionate," "liberal," and not on the grounds of results achieved.

Notice that this new class is in the business of manufacturing social environment. By monkeying with the social environment, the new class will, it implicitly claims, increase human felicity. Of course, such social engineering turns out to be devilishly expensive, but no matter — it is "moral." Notice, too, that if some heretic steps forward to question the absolute claims of "environment," the new class defends itself against him savagely. If perfectly respectable academicians, such as Jencks and Herrenstein at Harvard and Jensen at Berkeley, murmur dark things about "heredity," thus directly threatening new class -social-environmental claims, the response is vicious. For the new class, to call such heretics "racists" is the precise analog of the epithet "Bolshevik" as employed by the old capitalist elite. Real economic and class interests are thus defended by moral slander.

In the antiquated Marxist model, society is supposed to resemble a pyramid, with a tiny capitalist elite exploiting the masses toiling below. As Robert Whitaker has pointed out in a brilliant new book entitled A Plague on Both Your Houses, this antique model hardly describes our present circumstance. American society actually resembles an egg, broadest in the social middle. At the top, increasingly prominent and aggressive among competing elites, are the new-class liberal Social Concern exploiters, busy "reordering our priorities." At the bottom of the egg are their purported beneficiaries, who get little enough of the multi-billion take. In the middle of the egg are the middle and working classes, who pay the bills and support the new class of Social Concern professionals in the style to which they have recently become accustomed.

My third point, touching upon foreign policy, can be put much more briefly. It seems to me that the American Left (liberals and on over to radicals), has been, since World War II at least, in some disarray on the freedom issue. No doubt the Soviet Union has very few apologists anywhere these days; the stench from the Gulag is just too strong. Mao's China, however, has plenty of admirers; many also actively desired and worked for a Communist triumph in Vietnam; and many admire the various Third World "liberation" movements, most of which are Marxist and totalitarian in character. It may be a small point, but I sat through the entire Democratic Convention in Madison Square Garden this year and did not hear the word "freedom" mentioned once — though, of course, "compassion" was a key word in all speeches. Perhaps not surprisingly, an effort to mention Alexander Solzhenitsyn in the Democratic platform was quietly squashed in committee.

Yes, yes, I know, I will address myself to Franco and Pinochet in a moment.

Recently, as I was meditating upon a subject for my regular newspaper column, my gaze fell upon a headline in, as it happened, the New York Times sports section: "Miss Navratilova Cries Some a Year After Defection." Miss Navratilova is the Czech tennis star who defected a year ago and now resides mostly in the U.S.

Like everyone else, I had read the words "defect" and "defector" thousands of times before, but this time they struck me with the force of revelation, and I grasped their true meaning for the first time.

If I myself traveled abroad for an extended period, if I took a job in Paris, say, and moved my belongings there, I would not be called a "defector." I would be "an American living abroad" — as thousands in fact do. T. S. Eliot, who though born in St. Louis became a British subject, is not known as "Eliot, the famous defector."

The use of the term to describe Navratilova and others like her really implies the claim of the Communist state to total control over the individual. She is not working for the CIA. She merely wants to play tennis where she pleases. You can unpack the term "defector" and find within it the walls and barbed wire, armed towers and check-points, the entire repressive apparatus of the state, designed to enforce that total control. The word "defector" is also pejorative. When we use it, we accept the Communist valuation of the act. It is almost military in character (you can defect only to an enemy) and it therefore implies the unremitting hostility of the Communist state to everything outside it.

The Communist claim to total control seems almost historically unique, the single possible qualification to such uniqueness being the case of Nazi Germany. Under Franco, in contrast, tens of thousands of Spaniards worked abroad, traveling back and forth across the border without interference. There is no wall around Chile, as there is not around the other non-Communist authoritarian states. This distinction seems to me absolutely momentous. It means that these authoritarian states stand in an entirely different relation to their citizens. Yet the American liberal and radical is almost invariably more hostile to Franco's Spain or Pinochet's Chile than he is to any Com- munist state.

I would like to add, however, that 1 myself am not obsessed with the Communist problem — as some of the older generation of American rightists, such as Whitaker Chambers and Frank Meyer, seem to me to have been. After they broke with the Party they hated Communism, but also somehow respected it. For my generation of conservatives", Communism was never the "central experience" it was for Chambers, Meyer, and others.

I myself, for example, was born in 1930 and grew up in a normal middle-class environment. Communism was just not a real option. It seemed a repellent and self-evidently alien phenomenon. The few Communists I met during the 1930s and 1940s, usually in the public school system or some WPA project, confirmed this impression of alienness. They looked as if they had just gotten off the boat and would do very well to get right back on it. Their books and pamphlets sounded as if they had been translated from the Hungarian, and perhaps they were. 1 have always regarded the Soviet Union as a bleak and disgraceful tyranny, run by gray men with steel jaws, wide trousers, and shoulder holsters. As a seven-year-old, I rooted for the Finns.

WELL, there you have it. But given this spectrum of opinions and attitudes, how do I get along in the predominantly liberal atmosphere of the contemporary campus?

The answer is very nicely, thank you. First of all, liberalism at Dartmouth is relatively benign, and, like liberalism generally, on the defensive intellectually. Hanover in no way resembles, for example, the People's Republic of Berkeley. The presence here of a handful of New Lefists and Marxists proved to be minor and transitory. They were too busy screaming and yelling to do any serious academic work, and soon disappeared.

Let me hasten to add that I would not mind a bit if a competent scholar taught history or literature from a Marxist perspective. Eugene Genovese, for example, describes himself as a Marxist, and as a historian he would be an asset to any institution. Marx himself maintained, however, that the task of intellect is not to understand the world but to change it. That means understanding must be subordinate to political action. No academic institution can accept that set of priorities. The task of the academician is precisely to "understand" the world. Inquiry must be free, even if it damages someone's "cause." I would have to say that, unlike Eugene Genovese, the Marxist and New Left academicians I have known did in fact suppress other points of view, and treated their classrooms like political soap-boxes. A campus on which that sort of thing remained a powerful presence would be intolerable. Bringing politics into the classroom in a style of advocacy seems to me to constitute academic malpractice and also to be seriously infra dig, the sign of intellectual bad breeding. During the decade of intense U.S. involvement in Vietnam, for example, I cannot recall mentioning the word "Vietnam" once in the classroom.

My academic subject helps, here, of course, as does my methodology. I tend to stay close to the literary text itself. How would you, even if you so desired, bring Vietnam into the analysis of a poem by Alexander Pope?

It also helps, I suppose, that I do not lack opportunities for political self-expression elsewhere. I am a senior editor of National Review; my syndicated political column appears in some 200 newspapers; a President, two governors, a senator, and several cabinet officers have delivered speeches I've written. I even published a couple of essays in the NewRepublic last summer. I do not feel that I have to get into fights at cocktail parties.

Finally, some people manage to get along and some just do not. Civility and good humor rank high with me. My personality does not resemble that of Thorstein Veblen. I am sure that I am detested by some, mostly silently, and that many regard my opinions as deplorable, but in the latter group many also like to ski, play tennis, or hang around football practice with me. Existence, thank God, includes much more than opinions.

Jeffrey Hart '51, a specialist in 18th-centuryliterature, joined the Dartmouthfaculty in 1963.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMENAGE A HUIT

October 1976 By ROGERS E. M. WHITAKER -

Feature

FeatureRED BALLING IN THE JERSEY NIGHT

October 1976 By Jeffrey Brodrick -

Feature

FeatureFor Me and My Gal

October 1976 By ROGER BURRILL -

Article

Article'My Own House'

October 1976 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

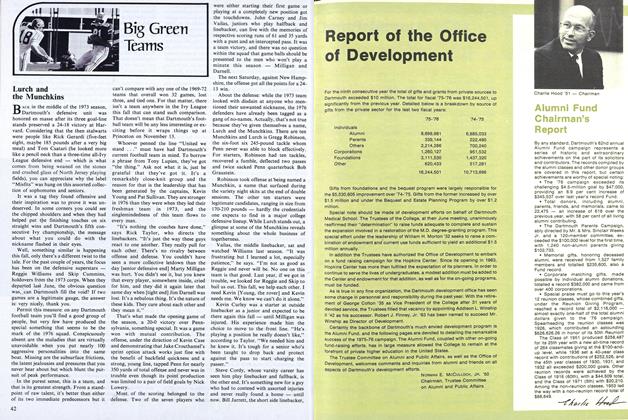

ArticleAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

October 1976 -

Article

ArticleLurch and the Munchkins

October 1976 By JACK DEGANGE

JEFFREY HART

Features

-

Feature

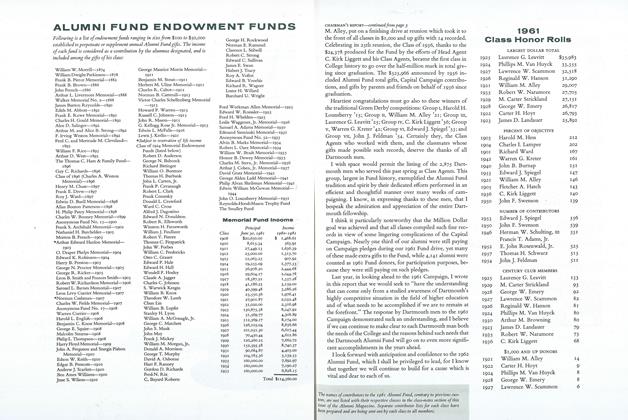

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureThe Honesty That Is Dartmouth

JULY 1963 By ALAN KENNETH PALMER '63 -

Feature

FeatureOut of the Amazon

MAY | JUNE 2018 By ANDREW FAUGHT -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

May 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureOMBUDSMAN

OCTOBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

March 1976 By McF.