KNOW THE QUALITY of the teaching that your children can look forward to, and you will know much about the effectiveness of the education they will receive. Teaching, tomorrow as in the past, is the heart of higher education.

It is no secret, by now, that college teaching has been on a plateau of crisis in the U.S. for some years. Much of the problem is traceable to money. Salaries paid to college teachers lagged far behind those paid elsewhere in jobs requiring similarly high talents. While real incomes, as well as dollar incomes, climbed for most other groups of Americans, the real incomes of college professors not merely stood still but dropped noticeably.

The financial pinch became so bad, for some teachers, that despite obvious devotion to their careers and obvious preference for this profession above all others, they had to leave for other jobs. Many bright young people, the sort who ordinarily would be attracted to teaching careers, took one look at the salary scales and decided to make their mark in another field.

Has the situation improved?

Will it be better when your children go to college?

Yes. At the moment, faculty salaries and fringe benefits (on the average) are rising. Since the rise started from an extremely disadvantageous level, however, no one is getting rich in the process. Indeed, on almost every campus the real income in every rank of the faculty is still considerably less than it once was. Nor have faculty salary scales, generally, caught up with the national scales in competitive areas such as business and government.

But the trend is encouraging. If it continues, tie financial plight of teachers—and the serious threat to education which it has posed—should be substantially diminished by 1970.

None of this will happen automatically, of course. For evidence, check the appropriations for higher education made at your state legislature's most recent session. If yours was like a number of recent legislatures, it "economized" —and professorial salaries suffered. The support which has enabled many colleges to correct the most glaring salary deficiencies must continue until the problem is fully solved. After that, it is essential to make sure that the quality of our college teaching—a truly crucial element in fashioning the minds and attitudes of your children—is not jeopardized again by a failure to pay its practitioners adequately.

THERE ARE OTHER ANGLES to the question of attracting and retaining a good faculty besides money.

► The better the student body—the more challeng- ing, the more lively its members—the more attractive is the job of teaching it. "Nothing is more certain to make teaching a dreadful task than the feeling that you are dealing with people who have no interest in what you are talking about," says an experienced professor at a small college in the Northwest.

"An appalling number of the students I have known were bright, tested high on their College Boards, and still lacked flair and drive and persistence," says another professor. "I have concluded that much of the difference between them and the students who are 'alive' must be traceable to their homes, their fathers, their mothers. Parents who themselves take the trouble to be interesting —and interested—seem to send us children who are interesting and interested."

► The better the library and laboratory facilities, the more likely is a college to be able to recruit and keep a good faculty. Even small colleges, devoted strictly to undergraduate studies, are finding ways to provide their faculty members with opportunities to do independent reading and research. They find it pays in many ways: the faculty teaches better, is more alert to changes in the subject matter, is less likely to leave for other fields.

The better the public-opinion climate toward teachers in a community, the more likely is a faculty to be strong. Professors may grumble among themselves about all the invitations they receive to speak to women's clubs and alumni groups ("When am I supposed to find the time to check my lecture notes?"), but they take heart from the high regard for their profession which such invitations from the community represent.

Part-time consultant jobs are an attraction to good faculty members. (Conversely, one of the principal checkpoints for many industries seeking new plant sites is, What faculty talent is nearby?) Such jobs provide teachers both with additional income and with enormously useful opportunities to base their classroom teachings on practical, current experience.

BUT COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES must do more than hold on to their present good teachers and replace those who retire or resign. Over the next few years many institutions must add to their teaching staffs at a prodigious rate, in order to handle the vastly larger numbers of students who are already forming lines in the admissions office.

The ability to be a college teacher is not a skill that can be acquired overnight, or in a year or two. A Ph.D. degree takes at least four years to get, after one has earned his bachelor's degree. More often it takes six or seven years, and sometimes 10 to 15.

In every ten-year period since the turn of the century, as Bernard Berelson of Columbia University has pointed out, the production of doctorates in the U.S. has doubled. But only about 60 per cent of Ph.D.'s today go into academic life, compared with about 80 per cent at the turn of the century. And only 20 per cent wind up teaching undergraduates in liberal arts colleges.

Holders of lower degrees, therefore, will occupy many teaching positions on tomorrow's college faculties.

This is not necessarily bad. A teacher's ability is not always defined by the number of degrees he is entitled to write after his name. Indeed, said the graduate dean of one great university several years ago, it is high time that "universities have the courage ... to select men very largely on the quality of work they have done and softpedal this matter of degrees."

IN SUMMARY, salaries for teachers will be better, larger numbers of able young people will be attracted into the field (but their preparation will take time), and fewer able people will be lured away. In expanding their faculties, some colleges and universities will accept more holders of bachelor's and master's degrees than they have been accustomed to, but this may force them to focus attention on ability rather than to rely as unquestioningly as in the past on the magic of a doctor's degree.

Meanwhile, other developments provide grounds for cautious optimism about the effectiveness of the teaching your children will receive.

THE TV SCREEN

TELEVISION, not long ago found only in the lounges of dormitories and student unions, is now an accepted teaching tool on many campuses. Its use will grow. "To report on the use of television in teaching," says Arthur S. Adams, past president of the American Council on Education, "is like trying to catch a galloping horse."

For teaching closeup work in dentistry, surgery, and laboratory sciences, closed-circuit TV is unexcelled. The number of students who can gaze into a patient's gaping mouth while a teacher demonstrates how to fill a cavity is limited; when their place is taken by a TV camera and the students cluster around TV screens, scores can watch —and see more, too.

Television, at large schools, has the additional virtue of extending the effectiveness of a single teacher. Instead of giving the same lecture (replete with the same jokes) three times to students filling the campus's largest hall, a professor can now give it once—and be seen in as many auditoriums and classrooms as are needed to accommodate all registrants in his course. Both the professor and the jokes are fresher, as a result.

How effective is TV? Some carefully controlled studies show that students taught from the fluorescent screen do as well in some types of course (e.g., lectures) as those sitting in the teacher's presence, and sometimes better. But TV standardizes instruction to a degree that is not always desirable. And, reports Henry H. Cassirer of UNESCO, who has analyzed television teaching in the U.S., Canada, Great Britain, France, Italy, Russia, and Japan, students do not want to lose contact with their teachers. They want to be able to ask questions as instruction progresses. Mr. Cassirer found effective, on the other hand, the combination of a central TV lecturer with classroom instructors who prepare students for the lecture and then discuss it with them afterward.

TEACHING MACHINES

HOLDING GREAT PROMISE for the improvement of instruction at all levels of schooling, including college, are programs of learning presented through mechanical self, teaching devices, popularly called "teaching machines."

The most widely used machine, invented by Professor Frederick Skinner of Harvard, is a box-like device with three windows in its top. When the student turns a crank, an item of information, along with a question about it, appears in the lefthand window (A). The student writes his answer to the question on a paper strip exposed in another window (B). The student turns the crank again— and the correct answer appears at window A.

Simultaneously, this action moves the student's answer under a transparent shield covering window C, so that the student can see, but not change, what he has written. If the answer is correct, the student turns another crank, causing the tape to be notched; the machine will by-pass this item when the student goes through the series of questions again. Questions are arranged so that each item builds on previous information the machine has given.

Such self-teaching devices have these advantages:

Each student can proceed at his own pace, whereas classroom lectures must be paced to the "average" student —too fast for some, too slow for others. "With a machine," comments a University of Rochester psychologist, "the brighter student could go ahead at a very fast pace."

The machine makes examinations and testing a rewarding and learning experience, rather than a punishment. If his answer is correct, the student is rewarded with that knowledge instantly; this reinforces his memory of the right information. If the answer is incorrect, the machine provides the correct answer immediately. In large classes, no teacher can provide such frequent—and indi- vidual—-rewards and immediate corrections.

The machine smooths the ups and downs in the learning process by removing some external sources of anxieties, such as fear of falling behind.

If a student is having difficulty with a subject, the teacher can check back over his machine tapes and find the exact point at which the student began to go wrong. Correction of the difficulty can be made with precision, not gropingly as is usually necessary in machineless classes.

Not only do the machines give promise of accelerating the learning process; they introduce an individuality to learning which has previously been unknown. "Where television holds the danger of standardized instruction," said John W. Gardner, president of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, in a report to then-President Eisenhower, "the self-teaching device can individualize instruction in ways not now possible—and the student is always an active participant." Teaching machines are being tested, and used, on a number of college campuses and seem certain to figure prominently in the teaching of your children.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE SHAPE OF DARTMOUTH 1969

April 1962 By C.E.W -

Feature

FeatureMost Exciting Place on Campus

April 1962 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38, -

Feature

FeatureWho will pay—and how?

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTPC: MASTER PLANNER

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Role for the Alumni?

April 1962 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26, -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Ongoing Purpose

April 1962

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA New Educational Program

April 1957 -

Feature

FeatureAnd More

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureDinner for the Colonel

March 1977 By BRAVIG IMBS -

Feature

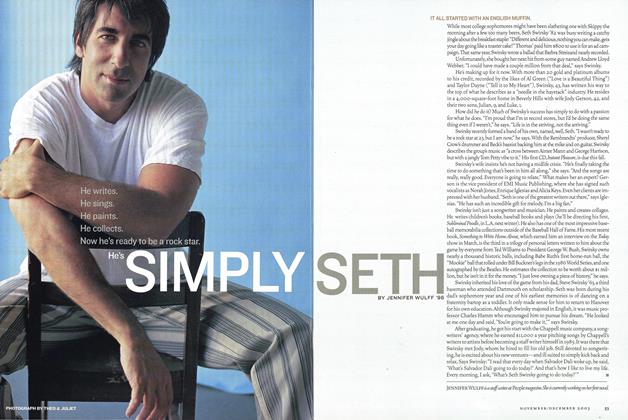

FeatureSimply Seth

Nov/Dec 2003 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

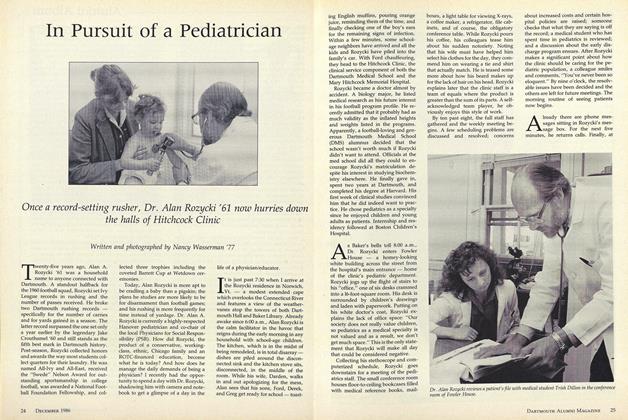

FeatureIn Pursuit of a Pediatrician

DECEMBER • 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BUILD YOUR OWN IGLOO

Jan/Feb 2009 By NORBERT YANKIELUN, TH'92