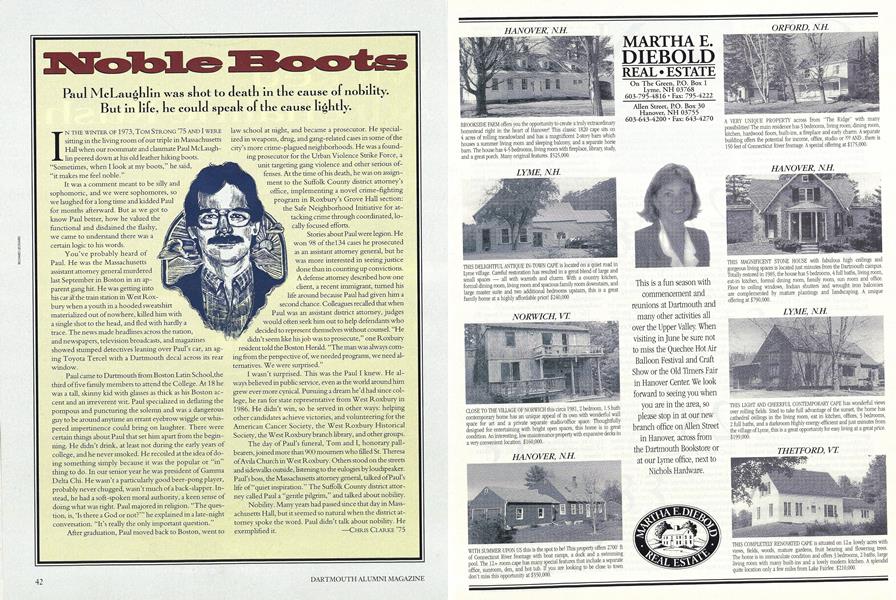

Paul McLaughlin was shot to death in the cause of nobility. But in life, he could speak of the cause lightly.

IN THE WINTER OF 1973, TOM STRONG '75 AND I WERE sitting in the living room of our triple in Massachusetts Hall when our roommate and classmate Paul McLaughlin peered down at his old leather hiking boots. "Sometimes, when I look at my boots," he said, "it makes me feel noble."

It was a comment meant to be silly and sophomoric, and we were sophomores, so we laughed for a long time and kidded Paul for months afterward. But as we got to know Paul better, how he valued the functional and disdained the flashy, we came to understand there was a certain logic to his words.

You've probably heard of Paul. He was the Massachusetts assistant attorney general murdered last September in Boston in an apparent gang hit. He was getting into his car at the train station in West Roxbury when a youth in a hooded sweatshirt materialized out of nowhere, killed him with a single shot to the head, and fled with hardly a trace. The news made headlines across the nation, and newspapers, television broadcasts, and magazines showed stumped detectives leaning over Paul's car, an aging Toyota Tercel with a Dartmouth decal across its rear window.

Paul came to Dartmouth from Boston Latin School, the third of five family members to attend the College. At 18 he was a tall, skinny kid with glasses as thick as his Boston accent and an irreverent wit. Paul specialized in deflating the pompous and puncturing the solemn and was a dangerous guy to be around anytime an errant eyebrow wiggle or whispered impertinence could bring on laughter. There were certain things about Paul that set him apart from the beginning. He didn't drink, at least not during the early years of college, and he never smoked. He recoiled at the idea of doing something simply because it was the popular or "in" thing to do. In our senior year he was president of Gamma Delta Chi. He wasn't a particularly good beer-pong player, probably never chugged, wasn't much of a back-slapper. Instead, he had a soft-spoken moral authority, a keen sense of doing what was right. Paul majored in religion. "The question, is, 'Is there a God or not?'" he explained in a late-night conversation. "It's really the only important question."

After graduation, Paul moved back to Boston, went to law school at night, and became a prosecutor. He specialized in weapons, drug, and gang-related cases in some of the city's more crime-plagued neighborhoods. He was a founding prosecutor for the Urban Violence Strike Force, a unit targeting gang violence and other serious offenses. At the time of his death, he was on assignment to the Suffolk County district attorney's office, implementing a novel crime-fighting program in Roxbury's Grove Hall section: the Safe Neighborhood Initiative for attacking crime through coordinated, locally focused efforts.

Stories about Paul were legion. He won 98 of the 134 cases he prosecuted as an assistant attorney general, but he was more interested in seeing justice done than in counting up convictions. A defense attorney described how one client, a recent immigrant, turned his life around because Paul had given him a second chance. Colleagues recalled that when Paul was an assistant district attorney, judges would often seek him out to help defendants who decided to represent themselves without counsel. "He didn't seem like his job was to prosecute," one Roxbury resident told the Boston Herald. "The man was always coming from the perspective of, we needed programs, we need alternatives. We were surprised."

I wasn't surprised. This was the Paul I knew. He always believed in public service, even as the world around him grew ever more cynical. Pursuing a dream he'd had since college, he ran for state representative from West Roxbury in 1986. He didn't win, so he served in other ways: helping other candidates achieve victories, and volunteering for the American Cancer Society, the West Roxbury Historical Society, the West Roxbury branch library, and other groups.

The day of Paul's funeral, Tom and I, honorary pallbearers, joined more than 900 mourners who filled St. Theresa of Avila Church in West Roxbury. Others stood on the streets and sidewalks outside, listening to the eulogies by loudspeaker. Paul's boss, the Massachusetts attorney general, talked of Paul's life of "quiet inspiration." The Suffolk County district attorney called Paul a "gentle pilgrim," and talked about nobility.

Nobility. Many years had passed since that day in Mass-achusetts Hall, but it seemed so natural when the district attorney spoke the word. Paul didn't talk about nobility. He exemplified it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

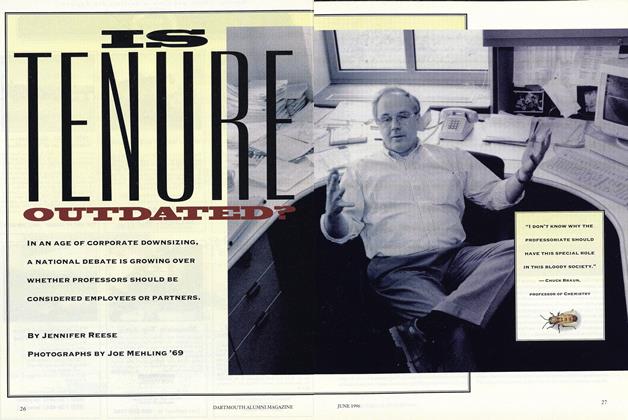

Cover StoryIS TENURE OUTDATED?

June 1996 By JENNIFER REESE -

Feature

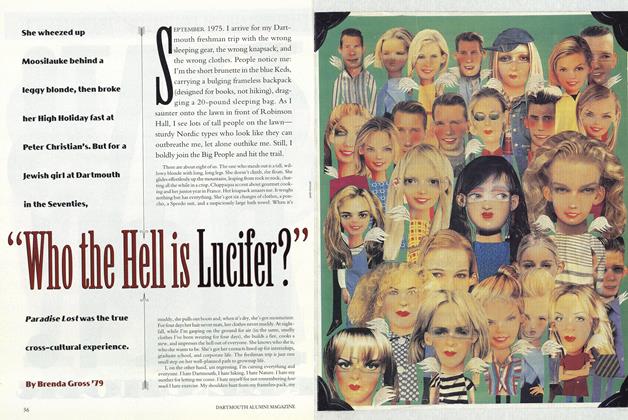

Feature“Who the Hell is Lucifer?”

June 1996 By Brenda Gross ’79 -

Feature

FeatureAMEN! TO THE GOSPEL CHOIR

June 1996 By Suzanne Leonard ’96 -

Article

ArticleUnderground Reading

June 1996 By Kathleen Burge ’89 -

Article

ArticleOffice Hours

June 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe First Four-Minute Mile and the Last Coverup?

June 1996 By “E. Wheelock”

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRetiring Professors

June 1974 -

Feature

FeatureEqual Opportunity

April 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAbandon All Hope

April 1981 -

COVER STORY

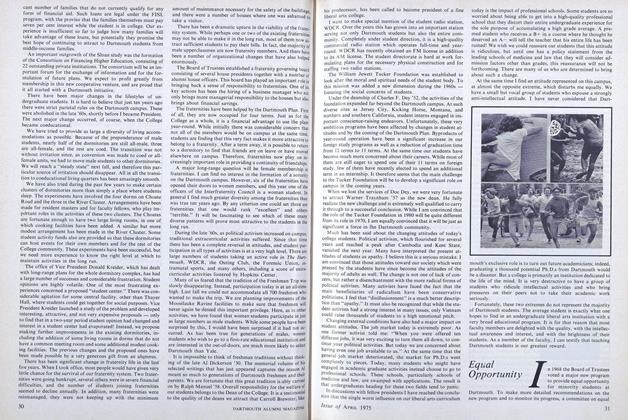

COVER STORYNature Worship

MAY | JUNE 2019 By jim collins ’84 -

Feature

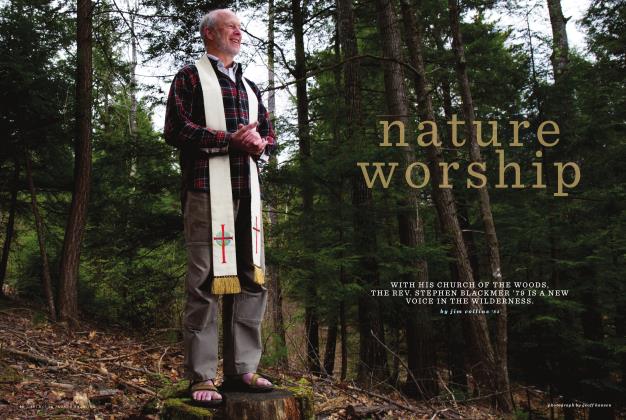

FeatureJoy Kenseth's Wonder Room

APRIL 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

Cover Story"The Art of Making Things Right"

September 1986 By PETER J. ROBBIE '69