LAST FALL, more than one million students enrolled in the freshman classes of U.S. colleges and universities. They came from wealthy families, middle- income families, poor families; from all races, here and abroad; from virtually every religious faith.

Over the next ten years, the number of students will grow enormously. Around 1964 the long-predicted "tidal wave" of young people, born in the postwar era and steadily moving upward through the nation's school systems ever since, will engulf the college campuses. By 1970 the population between the ages of 18 and 21—now around 10.2 million—will have grown to 14.6 million. College enrollment, now less than 4 million, will be at least 6.4 million, and perhaps far more.

The character of the student bodies will also have changed. More than half of the full-time students in the country's four-year colleges are already coming from lower-middle and low income groups. With expanding scholarship, loan, and self-help programs, this trend will continue strong. Non-white college students—who in the past decade have more than doubled in number and now compose about 7 per cent of the total enrollment—will continue to increase. (Non-whites formed 11.4 per cent of the U.S. population in the 1960 census.) The number of married students will grow. The average age of students will continue its recent rise.

The sheer force of this great wave of students is enough to take one's breath away. Against this force, what chance has American higher education to stand strong, to maintain standards, to improve quality, to keep sight of the individual student?

And, as part of the gigantic population swell, what chances have your children?

TO BOTH QUESTIONS, there are some encouraging answers. At the same time, the intelligent parent will not ignore some danger signals.

FINDING ROOM FOR EVERYBODY

NOT EVERY COLLEGE or university in the country is able to expand its student capacity. A number have concluded that, for one persuasive reason or another, they must maintain their present enrollments. They are not blind to the need of American higher education, in the aggregate, to accommodate more students in the years ahead; indeed, they are keenly aware of it. But for reasons of finance, of faculty limitations, of space, of philosophy, of function, of geographic location—or of a combination of these and other restrictions—they cannot grow.

Many other institutions, public and private, are expand- ing their enrollment capacities and will continue to do so:

Private institutions: Currently, colleges and universities under independent auspices enroll around 1,500,000 students—some 40 per cent of the U.S. college population. In the future, many privately supported institutions will grow, but slowly in comparison with publicly supported institutions. Thus the total number of students at private institutions will rise, but their percentage of the total college population will become smaller.

Public institutions: State and locally supported colleges and universities are expanding their capacity steadily. In the years ahead they will carry by far the heaviest share of America's growing student population.

Despite their growth, many of them are already feeling the strain of the burden. Many state institutions, once committed to accepting any resident with a high-school diploma, are now imposing entrance requirements upon applicants. Others, required by law or long tradition not to turn away any high-school graduate who applies, resort in desperation to a high flunk-out rate in the freshman year in order to whittle down their student bodies to manageable size. In other states, coordinated systems of higher education are being devised to accommodate students of differing aptitudes, high-school academic records, and career goals.

Two-year colleges: Growing at a faster rate than any other segment of U.S. higher education is a group comprising both public and independently supported institutions: the two-year, or "junior," colleges. Approximately 600 now exist in the United States, and experts estimate that an average of at least 20 per year will be established in the coming decade. More than 400 of the two-year institutions are community colleges, located within commuting distance of their students.

These colleges provide three main services: education for students who will later transfer to four-year colleges or universities (studies show they often do as well as those who go directly from high school to a four-year institution, and sometimes better), terminal training for vocations (more and more important as jobs require higher technical skills), and adult education and community cultural activities.

Evidence of their importance: One out of every four students beginning higher education today does so in a two-year college. By 1975, the ratio is likely to be one in two.

Branch campuses: To meet local demands for educa- tional institutions, some state universities have opened branches in population centers distant from their main campuses. The trend is likely to continue. On occasion, however, the "branch campus" concept may conflict with the "community college" concept. In Ohio, for example, proponents of community two-year colleges are currently arguing that locally controlled community institutions are the best answer to the state's college-enrollment problems. But Ohio State University, Ohio University, and Miami University, which operate off-campus centers and whose leaders advocate the establishment of more, say that taxpayers get better value at lower cost from a university-run branch-campus system.

Coordinated systems: To meet both present and future demands for higher education, a number of states are attempting to coordinate their existing colleges and universities and to lay long-range plans for developing new ones.

California, a leader in such efforts, has a "master plan" involving not only the three main types of publicly supported institutions—the state university, state colleges, and locally sponsored two-year colleges. Private institutions voluntarily take part in the master planning, also.

With at least 661,000 students expected in their colleges and universities by 1975, Californians have worked out a plan under which every high-school graduate will be eligible to attend a junior college; the top one-third will be eligible for admission to a state college; and the top one-eighth will be eligible to go directly from high school to the University of California. The plan is flexible: students who prove themselves in a junior college, for example, may transfer to the university. If past experience is a guide, many will—with notable academic success.

THUS IT IS LIKELY that somewhere in America's nearly 2,000 colleges and universities there will be room for your children.

How will you—and they—find it?

On the same day in late May of last year, 33,559 letters went out to young people who had applied for admission to the 1961 freshman class in one or more of the eight schools that compose the Ivy League. Of these letters, 20,248 were rejection notices.

Not all of the 20,248 had been misguided in applying. Admissions officers testify that the quality of the 1961 applicants was higher than ever before, that the competition was therefore intense, and that many applicants who might have been welcomed in other years had to be turned away in '61.

Even so, as in years past, a number of the applicants had been the victims of bad advice—from parents, teachers, and friends. Had they applied to other institutions, equally or better suited to their aptitudes and abilities, they would have been accepted gladly, avoiding the bitter disappointment, and the occasional tragedy, of a turndown.

The Ivy League experience can be, and is, repeated in dozens of other colleges and universities every spring. Yet, while some institutions are rejecting more applications than they can accept, others (perhaps better qualified to meet the rejected students' needs) still have openings in their freshman classes on registration day.

Educators, both in the colleges and in the secondary schools, are aware of the problems in "marrying" the right students to the right colleges. An intensive effort is under way to relieve them. In the future, you may expect:

Better guidance by high-school counselors, based on improved testing methods and on improved understanding of individual colleges and their offerings.

Better definitions, by individual colleges and universities, of their philosophies of admission, their criteria for choosing students, their strengths in meeting the needs of certain types of student and their weakness in meeting the needs of others.

Less parental pressure on their offspring to attend: the college or university that mother or father attended; the college or university that "everybody else's children" are attending; the college or university that enjoys the greatest sports-page prestige, the greatest financial-page prestige, or the greatest society-page prestige in town.

More awareness that children are different from one another, that colleges are different from one another, and that a happy match of children and institutions is within the reach of any parent (and student) who takes the pains to pursue it intelligently.

Exploration—but probably, in the near future, no widespread adoption—of a central clearing-house for college applications, with students stating their choices of colleges in preferential order and colleges similarly listing their choices of students. The "clearing-house" would thereupon match students and institutions according to their preferences.

Despite the likely growth of these practices, applying to college may well continue to be part-chaos, part-panic, part-snobbishness for years to come. But with the aid of enlightened parents and educators, it will be less so, tomorrow, than it is today.

COPYRIGHT 1962 BY EDITORIAL PROJECTS FOR EDUCATION

ILLUSTRATIONS BY PEGGY SOUCHECK

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE SHAPE OF DARTMOUTH 1969

April 1962 By C.E.W -

Feature

FeatureMost Exciting Place on Campus

April 1962 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38, -

Feature

FeatureWho will pay—and how?

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureTPC: MASTER PLANNER

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Role for the Alumni?

April 1962 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26, -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Ongoing Purpose

April 1962

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Administration

June 1980 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Rise of Research

FEBRUARY 1989 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

FeatureBERNSTEIN

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

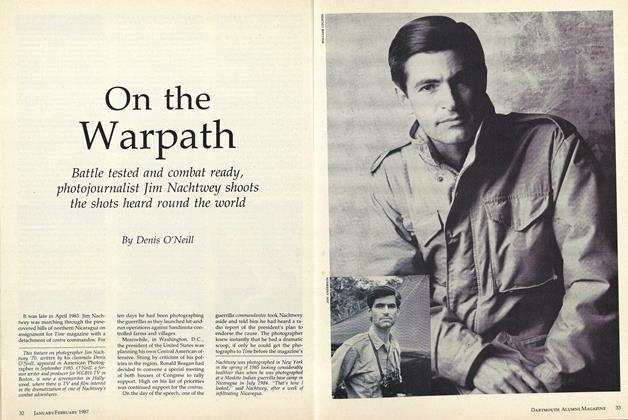

FeatureOn the Warpath

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 By Denis O'Neill -

Feature

FeatureA simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple...

February 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH