here are moments Of my life, so full, so vibrant, that grief overwhelms me. And this, for me, is progress.

My husband and I have just made love. I sit on Steve's lap, cheek caressing cheek, the stubble of his day-old beard sweet sandpaper to my smooth skin. His strong, former baseball-player arms envelop me. I look over his shoulder, through the bay windows at the small-town harbor of Bristol, Rhode Island, where we've made our home. It has been kind to us, that harbor. Watching the fiery skies of the setting sun and singing, "Daisy, Daisy," we've ridden our tandem bike along its shore. We've canoed upon it on glassy-lake days and days when we should have known better, when wind and waves crested over the bow of our little vessel drenching me in laughing water. And we've played silly tricks, paddling out to my mother's sailboat and leaving pretend notes from the Coast Guard about problems with her craft. If a swift resolution was not made, we threatened her with "What-For." The exact words she had once used to strike fear into her children's hearts, this of course immediately gave the culprit away. You could say, being kind to me, that subtlety is not my strong suit.

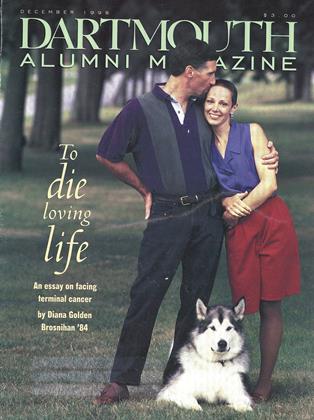

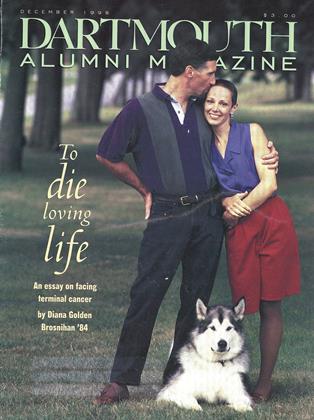

I see, too, the chestnut tree under which we were married, or mostly married, not quite one year ago. In a circle of 18 adults, one toddler, an infant, and three dogs, our ceremony began there. My first child was amongst us, a 100-pound Alaskan malamute, who, much to Steve's chagrin, lay at my foot throughout the ceremony. Steve and Midnight Sun suffer a male rivalry for my attentions. We sat in the shade of the tree's broad branches. In the midst of us, two of the dogs had a wrestling match.

Thunder and rain began. We ran for cover and ended up in a football huddle singing "Stand By Me," and shouting our vows so they could be heard over the pounding rain and the roaring voice of the sky.

Here and now, pressed against Steve so tightly that I cannot tell where I end and he begins, I am connected to life by the glue of love. It is a great irony. For it is this connection that is so bittersweet.

Recently, I told Steve that I would give my right leg for a normal body. We both laughed. It is one of those self-contradictory statements, like the.box around the phrase, "Everything in this box is a lie." It is a piece of the black humor that helps keep me sane.

At the age of 121 lost my right leg to bone cancer. Following that, I had a year and a half of high-dose chemotherapy. Monday through Thursday in the hospital every three weeks. It was not the devastating experience that most people expect and, quite possibly, some of my victims would have appreciated it if I had been a bit more depressed. My hospital buddies and I planted realistic rubber snakes on the linoleum floors and made the nurses scream. In my bedpan, I mixed Jean Nate and rubbing alcohol together and handed it in, a tainted sample for a urine test. I hid my artificial leg, realistically dressed in argyle sock and penny loafer, in one of my classmate's beds on an eighthgrade grade French class school trip to Quebec City. The poor boy discovered it as he dove, headfirst, into his bed that night.

I began skiing on one leg seven months after the amputation with the local disabled skiing program at Mt Sunapee in New Hampshire. There, among Vietnam vets who'd had arms and legs blown off, paraplegics, and blind men and women, I found my mentors. No-holds-barred people w ho skied with a grace and abandon I could only dream of. With them I found what was to be the driving force of my life for the next 15 years, ski racing. I wrote my Dartmouth application essay about Jonathan Livingston Seagull. His quest for perfect flight I claimed as mine for the perfect turn. I never attained that, of course, but the dream—combined with hill sprints, stomach routines, and forests of slalom courses—transformed me from a klutz to a fulltime athlete on the U.S. Disabled Ski Team.

Over the course of my career I won an Olympic gold medal and 19 golds in world and national championships. I was named the " 1988 U.S. Female Alpine Skier of the Year" by the U.S. Olympic Committee—the first time that an athlete with a disability was chosen over all the other athletes in the sport. I was the first athlete with a disability to be inducted into the U.S. Ski Hall of Fame and the International Women's Sports Hall of Fame. I tell you this both to toot my own little horn and, also, to give you the context of who I was, or who I thought I was.

After ski racing, I moved to Colorado and started my own business, "Golden Opportunities. As I'd trained for skiing, I trained for my new passion, public speaking, by taking improv classes, voice lessons, and speech classes. I became an international inspirational speaker. It was a delightful twist. As a child, I was such a blabbermouth that my weary family had often gladly paid me 25 cents to be quiet for a precious half hour.

Six months after I started Golden Opportunities, I found a lump in my right breast. Upon awaking from the biopsy, I learned I had cancer, again, and I'd need a mastectomy. I thought about my teammates who were missing so many body parts and I decided, quite rationally, that I could handle this. Pathology results came in. The surgeon shocked me bv suggesting thev do a second biopsy on the left side for some "suspicious spots." I awoke from the second biopsy to the echo of the word "cancer." The news stung, but, as was my style, I joked it off. Just before my bilateral mastectomies and the start of six more months of chemotherapy, I told my friends I'd keep them "a breast" of the situation.

Ten days after the mastectomies, I hopped a flight to San Francisco to give a speech to an audience of 900 people. Cancer had not stopped me as a child. It would not stop me now. After my talk, a close friend accompanied me to the hotel pool and my first attempt at exercise since the operation. I used to swim as part of my training regimen. There was nothing more peaceful than the steady rhythmic repetition of four long strokes followed by a deep breath in the timeless crossing of a crisp, clear mountain lake. I pictured this as I leapt confidently into the deep end of the pool. But I could not get my arms over my head, and my single leg would not propel me forward. As I sank, the panic rose. It rose and crashed down upon me like an ocean wave that effortlessly tumbles you and draws you under. My friend jumped in, grabbed me, and swam me to the shallow end of the pool. "Why," he teased, as he held me, while I cried from the fear and the frustration of starting over once again, "must you always dive in over your head?"

In the midst of all this, I was a couple of months into a relationship with a whitebearded man the same age as my father, a university professor of engineering who rode a Harley and led school treks in Nepal. He was married. He had had other girlfriends. His wife knew about us. She sent food to me after my first biopsy. One day, when returning with him from an afternoon liaison in the mountains, we met his wife on the street corner. I listened in stunned silence as they talked about the weather.

The affair ripped me apart. "I'll never get involved with a married man," I had vowed years before with full conviction. "Only weak-willed women do that." But, now, here I was incapable of detaching myself. This father-figure, who accompanied me to every chemo treatment, read me to sleep at night, and shared in the mostprivate private thoughts of my journal was my fantasized oasis. I clung to him like that longed-for for drink in the desert. But the mirage faded each night at midnight when he left me to go home, leaving me parched.

Despite my plans, I got sick from chemo treatments. Infections fections, fevers, and teeth that needed to be pulled forced me to cancel some of my talks. Several months into my treatments my gynecologist found a large growth in my uterus which he felt needed to be removed. I awoke from that surgery to the words, "We had to remove your uterus."

It was not the holocaust of my body that was the worst. It was the fall from grace that accompanied it. The crumbling of my mind. I started to hyperventilate. The nurse kept repeating "You're safe now. You're okay. You're out of surgery. You're safe."

Safe? I couldn't see straight. I couldn't hear anything beyond the noise of my mind, going round and round telling the world that this was too much. Stop. I pleaded. Take myleg. Take my breasts. But not my ability to havechildren. The rape of some indifferent power over my body. "God only gives you as much as you can handle," I've often heard said. I believed it until that day.

Some nights I sat on my bedroom floor, my knee against my scarred chest raging at the gods' game of tug-of-war. Wishing that the cancer would take me. Furious at myself for that wish. The woman who had managed my office left the day after I finished chemo, giving me five minutes' notice, and started a lawsuit against me. My triangle relationship was too complex plex. I took an overdose of sleeping pills and, then, called a friend, realizing I didn't want to do this.

I tried different things to pull myself up. I got a puppy to celebrate the end of chemo. A four-and-a-half-month-old Alaskan malamute named Prizzy. Born on Valentine's Day, her name was short for "Prisoner of Love." For five weeks she was my constant companion. She once got up to lick the wounds of a bleeding cub my sister and I watched on the television screen. Five weeks later, because of non-stop grand mal seizures, she had to be put to sleep. That night, I checked into a psychiatric hospital for the first time. When I arrived on the ward, feeling pulled again by the undertow, one of the nurses' aids told me that I could either watch a game of chess that two of the inmates were playing or, if I preferred, I could join in a game of Trivial Pursuit.

In the autumn of that year, I decided to get another puppy, this time a 12 -week-old boy-brat. Midnight Sun, so named because I imagined him to be my light in the night, was full of mischief and contradiction. He towered over the other puppies we came across, but the day a Yorkshire terrier puppy barked at him, he climbed onto my lap and buried his head against me. If I tried to roll him on his back into the submissive position, he'd fight me with every ounce of his 20pound body. I had him trained to be a service dog. On one of our first flights together, Mid lay curled up at my foot. I fell asleep. He crept forward and licked the ankles of the woman in front of us. You should have heard her scream. For the first time in months, I was laughing again.

New Year's Eve, one year to the day after my first breast biopsy, I set off on a journey. Midnight Sun and I, my sleeping bag, tent, camping gear, and a knife I'd bought to protect myself piled into my old Jeep Wagoneer We set off to spend a couple of months driving around the country going wherever the mood struckme. Enough self-pity, I decided. It'sbeen a year. The cancer is gone. You've recoveredfrom, your surgeries.You've ended the affair. Your lawsuit has been settled andyou have Midnight Sun. It's time to get on with life. Leave the shitbehind. Get your shit together.

I fell apart. I could not make decisions. I'd drive up one road. Decide it was not the place to be. Return to where I began. Change my mind. Circles. I here was no music in the mountains that, before, had always sung to me. I saw no beauty in the wilds of the Southwest that had captured my heart so completely that once, feeling as lonely as if Id just left a lover, I'd cried on a flight back East after leaving the Grand Canyon. Day Three I took my knife and cut the inside of my left forearm. Not suicidal incisions. Just fascinated by the eerie powey: of drawing my own blood.

I returned home. My failure, the brutal noise of a thou- sand racquet balls slamming against the walls of my mind, crushed me. I crawled into the cubby hole under my desk. One of my best friends Jessica, a woman whom I'd met in the psychiatric hospital found me, my left arm a checkerboard of self-inflicted cuts. For the second time in less than a year I went back to the ward. The depression that had been there before remained, but this time I had gone over the edge. One of my doctor's notes says it so clinically, "She has continued psychological problems with a five-day in-patient hospital stay in early January at which time some of her behavior was deemed to be psychotic." Me, psychotic? Not Diana.Not the woman me article called"Princess Never Say Di, theGolden Girl." Not the Olympicgold medalist. Not the womanwho backpacked five days alonethrough the high Utah desertchanting, "I'm tough, strong, indomitable, whenever she feltlike sitting down and waiting for a helicopter rescue. Not the inspirational speaker who, once, truly believed that the power of willand passion with vision could accomplish anything. Psychotic.

When I left the hospital, I swore I never wanted to go back to that place of locked doors and babysitters. I needed some other method of healing. A friend suggested a retreat center, Esalen, on the Big Sur coast of California. I went there for a long-weekend, touchy-feely program. In one session widi my group I told them about my recent history and a nightmare I'd just had. In my dream, I stood on a gray linoleum floor in the middle of a large foyer of an institutional building. A man stood by the wall watching me closely, his white doctor's coat a stark contrast to the dirtiness of the walls. I screamed. No words—simply non-stop animal cries. He watched. When I stopped screaming I curled up onto the floor in the fetal position and withdrew from the world. Jessica came to me and tried to call me out of my isolated world. "Diana. Diana. I m here," she whispered in my ear. "Come back. Talk to me. Come back. You can do it. Just say something. Anything." The doctor told her that she had just a few more minutes to draw me out and if she didn't he would take me away and lock me up. "What a fascinating subject," he commented to no one in particular, "for a study of how much the human spirit can handle." I never emerged. So they took me away.

After I told the dream, the group leader at Esalen suggested that perhaps I needed to let go, momentarily, into the arms of the group. If I wanted, I could curl up into that fetal position with all 18 of them surrounding me, holding me, and there I could cry or scream or simply lie still until I was ready to emerge. They would wait. So I curled up, and, for a timeless period, lay sobbing in the arms of these people I barely knew. Like the Good Witch planting the kiss of protection on the forehead of Dorothy, everyone from the group kissed me on the forehead after I got up .

There was something so gentle, and so kind, about that experience. It helped me through a couple of years that contained many moments of simply going through the motions of living. Weeks when I couldn't find the energy to replace an empty roll of toilet paper in the holder. Days when I went alone into the desert and screamed into the echoing walls of a canyon. But there were also times of simple joy. Wrestling with Midnight Sun in my backyard, feeling his soft far against my hands. He was devious about sticking his wet, slurpy tongue in my face whenever I was unprepared. One day, falling on me, he even broke my little finger. It needed surgery. I laughed, happy to have an operation that would simply repair a part of my body, not take a part away.

Two years after my Esalen course I was thrown back off my precarious balance. My breast cancer had spread. It is now, as I write this, in about a dozen places in my skeletal system. At this stage the disease is "treatable, but not curable. "Terminal. Although whether that means I have one year or five is anyone's guess. As I tell my story, I'm afraid I must sound like the dream candidate for the 1950s TV show, "Queen for a Day," in which whoever told the saddest story won lots of appliances.

After I heard the news, I sold my home and my old Jeep and bought a BMW convertible. I moved from Colorado back East to be near my family. I donated all of my language learning tapes to charity. I dyed my hair blond before starting chemo treatments. I'd be losing my hair for the third time, so I figured, why not? I smoked my first joint and I stopped public speaking. Following my theory that honesty, not a stiff upper lip, is best, I also began to tell people about the terminal nature of my disease.

It was a mistake. Even now, I hesitate to use that word, not because of what it means to me. Call it what you will, my disease remains the same. Although I always hope for a miracle cure, the facts are that more than 40,000 women a year in the U.S. die from breast cancer after it metastasizes. But I found that many people want to believe that if your will is just strong enough, "You can beat this thing." And so I hesitate, because the word "terminal" has scared people into wanting to save me or wanting me to save myself. They mean well, but their voices start the racquet balls flying.

I have a friend who has a friend who has cancer. He took blue-green algae and he was cured; If you meditate for 15 minutesthree times a day, you can cure your cancer; Hold on, doctors arediscovering new cures every day; Reject the evils of Western med-icine; Keep a positive attitude; Drink Nani juice; Repent; Fast; Pray.

I gave out, again, under the weight of treatment decisions, the terror of being back on the fast track of bone scans, doctors, needles, and the loneliness of being in a world where so many conversations revolve around plans for the future. I checked into the psych ward two more times. I told the psychologist who held my hand for the next two years that there must be some path through this quagmire that ended in thriving. Above all else, what I wanted was to care about living. I wanted to die loving life, not indifferent to death.

I retreated to Peaks Island for the off-season. An island in Casco Bay off the coast of Portland, Maine, Peaks has a winter population of around 1,000. There I watched the sun rise and, on rare occasions, a golden moon rise, over the ocean from my bed. I took long walks with Midnight night Sun, throwing my sleeping bag in his saddle bags so I could keep warm while spending hours simply sitting on the rocky shore, watching the movement of the ocean and the sunlight dancing upon it, listening to the cries of gulls, smelling the salt thick on the air. I was making my peace with life, if not finding the thriving I longed for.

It was during this time that I met Steve Brosnihan at a Halloween party my brother and his wife had dragged me to. Steve in a black medieval knight costume with a gigantic fly head. Me in a silver lame sleeveless gown with long black gloves and a butterfly mask, pretending, for an evening, to be someone long forgotten, a sensual woman. He stopped me in passing. He remembered my smile from Dartmouth, where he'd been a year ahead of me. A baseball player who, when training, could not help but notice me jogging on my crutches around the track of Memorial Field and hopping up the stadium bleachers. At a bar in Boston, he'd watched me on the TV screen as I made my gold medal Olympic run. He'd even contacted me once to see if I could come speak at a camp for children with cancer. A cartoonist who works two nights a week at the local children's hospital drawing with children, Steve volunteers at Camp Hope one week out of every summer. After a return calland a pleasant chat, I had politely blown him off and him to call my manager to see if they could "Fit it into my schedule." Over the years, I had grown at least a little smarter. This time when he caught my attention, I grabbed his back.

At the time of the party, I had accepted what I thought to be the truth, that I would live alone for whatever amount of time I had left. I could not believe there would be a man strong enough to handle not only the baggage I would bring with me, but the likelihood of deathinthe not-too-distant future. A man I could trust I was wrong.

Our first date was spent at the Dana-Far-ber Cancer Institute. I had medical tests from 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. and was looking for a way to bring some fun into the day. On a long shot, I invited Steve to join me. To my amazement, he did. To this day, we still argue about who turned our parting peck-on-the-cheekkiss that evening into the romantic event it became. Steve claims it was me, but I'm writing this piece, so I tell you definitively that it was he. On our second date, Steve picked me up in his first car, the 1964 Chevy Bel Air wagon he'd owned and worked on since he was 15.

We recently took a three-week European vacation. It was my longest break from chemo in over a year and a half. Before we left, I bought Spanish tapes and studied for two months. During the trip we played dress-up and danced in gown and tux into the early morning hours. We listened to street-side sax players bringing the cobblestoned streets of old-town Barcelona to life. We laughed with the locals when, while attempting simple conversation in Spanish, we mistakenly called a kind gentleman a goat. An "insulto grande," as we soon found out. And I said to hell with all the theories people extol of macrobiotics curing cancer, and drank champagne and ate caviar, pastry, and lots of red meat.

There is a sweetness now to my life that has subtly slipped its way in. Certainly not always, but often. The water is more friendly, and I hear music again, in a wave cresting over the bow of our canoe, in the wolf-like howl of Midnight Sun, in the streets of Barcelona, in the cry of a lone seagull, and in the touch of my husband's hand as we sing out the refrain of "Stand By Me." Knowing what is likely ahead, there is a powerful sadness that comes with this re-found love of living. But this is a sadness I can bear. Connected where once I was fragmented, I now know that peace can come to a tormented mind, that there is beauty that stands in stark contrast to horror, and that there is love that comforts pain.

Heading home: Brosnihan walks with her four-year companion and source of solace, Midnight Sun.

Some nights I sat on my bedroom floor, my knee againstmy scarred chest, raging at the gods' game of tuh-of- war.

The fast track includes Neupogen two days a week to keep up the white blood cell count.

Amid changeable weather and moods, Bristol has provided a constant, watery harbor.

I said to bell with macrobiotics curing cancer; and drankchampagne and ate caviar; pastry, and lots of red meat.

Diana and Steve Brosnihan bask in the afternoon light. They sang "Stand By Me" at their wedding.

With an uncertain prognosis but new reason to care, Diana gets Midnight Sun to howl.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHere by the Fire

December 1998 By James Zug '91 -

Feature

FeaturePost What?

December 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

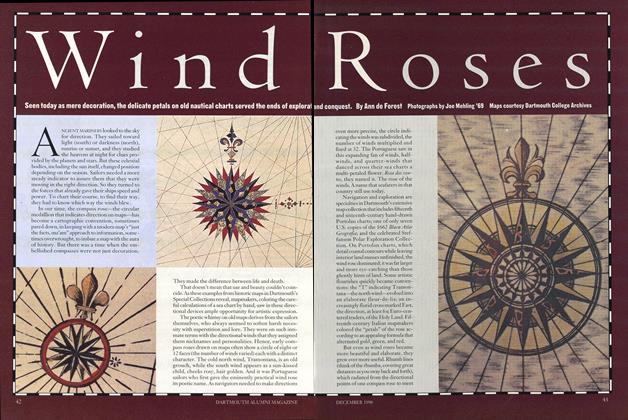

FeatureWind Roses

December 1998 By Ann de Forest -

Article

ArticlePrediction Fiction

December 1998 By Christine Schultz -

Class Notes

Class Notes1997

December 1998 By Abby Klingbeil -

Article

ArticleLooking for Frost

December 1998 By Noel Perrin

Diana Golden Brosnihan '84

Features

-

Feature

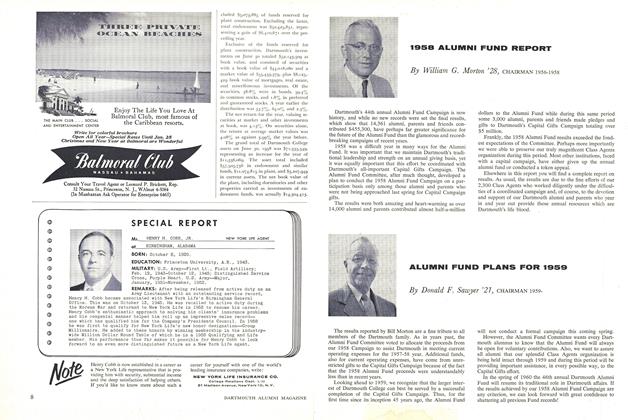

FeatureALUMNI FUND PLANS FOR 1959

DECEMBER 1958 By Donald F. Sawyer '21 -

Feature

FeatureKappa Kappa Grandpa

MAY 1985 By Gabrielle Guise '85 -

Feature

FeatureMy "Most Unforgettable Character"

February 1954 By JAMES L. MONTAGUE '28 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySecond Nature

OCTOBER 1996 By Jay Heinrichs -

FEATURES

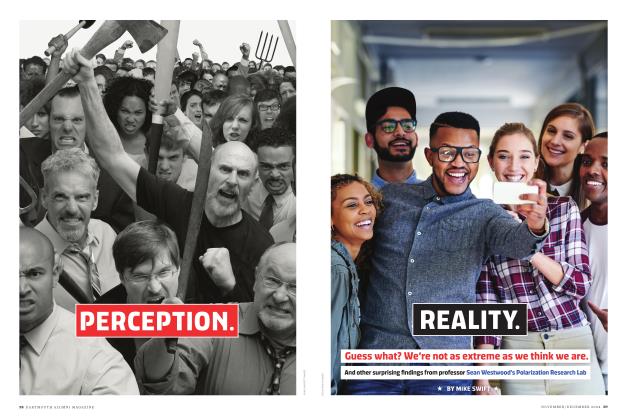

FEATURESPerception. Reality.

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2024 By MIKE SWIFT