Two words that pose a vital issue, both economic and political, that the U.S. "must now face with as much flexibility and perspective as it can muster."

DEAN OF SUMMER PROGRAMS

THOMAS MANN once said, "Ours is a political age and the destiny of modern man will be decided in political terms."

These words provide my starting point, because the nation must now face, with as much flexibility and perspective as it can muster, a vital issue in which the economic and political elements can not be separated — an issue on which we are going to hear much heated debate that will fail to relate the economic to the political aspects. I refer to the question of whether the United States should associate itself more closely with the governments of the Atlantic Community, whether in the Common Market or some other institution.

It is necessary to go into a little history, for without any consideration of where we have been, and how we got there, it is difficult to think very clearly about where we want to go, and how.

Let us go back about a hundred years. Something quite remarkable, and often forgotten, was going on between 1815, the end of the Napoleonic Wars, and 1914, when World War I began. This "something" was international organization, which began to develop simultaneously in three ways. The first way was international business. The second was what is sometimes called international non-governmental organization, and the third was international intergovernmental organization.

The first of these was the result of recognition by businessmen that some kinds of commercial activity could be better carried on through international companies. My research suggests that bankers were among the first to recognize this principle. We all know such names as Rothschild, Fugger, and de Medici. Merchants and communications men were not far behind in seeing possible advantages in internationalizing the structure of some of their enterprises.

In terms of numbers, the international businesses of the nineteenth century were few, as compared with the multitude of non-governmental organizations. These NGO's, as they are often called, spread like wildfire after the middle of the century. In fact, so fast was the expansion that by 1907 it was necessary to establish a Central Office of International Associations in order to keep track of them. As one man put it, "An international organization has at some time been constituted for nearly every sphere of human activity." The Central Office of International Associations became the Union of International Organizations in 1910, when the first Yearbook of International Organizations was published, listing 510 international organizations, only seventeen of which were intergovernmental.

The development of intergovernmental organizations was far slower than in the case of the private institutions, for very good reasons. Industry, commercial firms, and banks could internationalize whenever the directorates involved thought they could see a profit in doing so. Relatively few individuals had to be convinced of the advantages of internationalization, whereas in the governmental sphere very large numbers of people had to accept concepts and ideas that were new and different. Even college professors sometimes find it difficult to accept new ideas. In the NGO's, which were entirely voluntary, people in many countries banded themselves together to advocate whatever seemed to them, as individuals, to be desirable. There was, for example, an NGO that advocated the abolition of all alcoholic beverages, at the same time that there was one that fostered the drinking of wine. Governments were slow, and rightly slow, to join international agencies in which they might be committed to do anything. Before a government could join an international organization it had to be convinced that there was some recognizable benefit to be secured from membership, a benefit that would justify some consequent limitation upon a small aspect of national sovereignty.

When I use the phrase "international intergovernmental organization" I have something very specific in mind. To me, an international intergovernmental organization is one that has a constituent instrument (a charter or constitution) that sets forth specific functions and purposes, a staff of its own, a headquarters, and regular periodic meetings of policymaking organs. One of the first such international organizations was what we now know as the Universal Postal Union, which came into being in 1874. The UPU is a fine illustration of the interrelationship of the economic and the political because it was created as the result of pressure by businessmen upon governments. There was an acute need, in the rapidly expanding world of commerce of the mid-nineteenth century, because business could not be transacted without a dependable international system for exchange of mail.

IN the eighty-odd years after 1874 the number of international intergovernmental organizations increased rapidly, until by 1954, 222 of them had been created, of which 132 were still in existence. The United Nations was but one of the 132. In fact, so successful were these intergovernmental organizations that their number almost doubled every fifteen years from 1914 to 1954. Only twice have the governments of the world established international intergovernmental organizations with very broad purposes - the League of Nations and the United Nations. All the others have had much more limited functions.

In very few instances have international organizations been given any power other than the right to make recommendations to states. The success of the UPU is due to the fact that its recommendations are carried out by all members; if a state does not comply, other states will not handle its mail. The principle that the power of international organizations should be limited to the right to make recommendations remained the norm until the establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951. In this case, the departure from the experience of the past was very great, for the six governments that formed the Coal and Steel Community voluntarily gave up more national sovereignty than had ever been the case before. Here we have an outstanding example of flexibility and perspective.

After World War II there was a movement for European political unity, culminating in the defeat of the European Defense Community (EDC), which would have merged the military forces of several Western European states in order to provide all of them with a more effective national military defense. When it became clear that EDC could not be created, a few leaders in Europe, notably Jean Monnet of France, turned to consideration of other forms of international organization from which recognizable benefits might be secured. They looked at the world in which they lived and saw the immensely rich United States, with its high standard of living, stable government, and contented people. Monnet did not believe the time ripe to advocate a unified economy for France, West Germany, Belgium, The Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Italy. He was aware, however, that the key economic problem for these six states lay in the general area of their coal and steel industries, because both were fundamental to advanced economies. If the coal and steel industries of all six countries were to be strengthened, it would be necessary for each government to surrender a certain amount of control of these industries within its own borders. The problem was to find some means whereby each of the countries could gain more than it would lose. Monnet argued that this could not be accomplished unless each government agreed to surrender to an international body as much sovereignty as might be necessary, so that there could be a single authority to control and develop the iron and coal industries of all six together.

Before the ECSC could come into being, many powerful interests had to be convinced that, in the long run, each would be better off within a Coal and Steel Community than it would be outside. Labor had to be convinced that neither, unemployment nor lower wages would result from international regulation. Bankers had to be convinced that their investments in the coal and steel industries of their own countries would not be endangered. Mill and mine owners had to be convinced that they would not suffer while their competitors in the Community would flourish. Consumers had to be convinced that prices would not rise without simultaneous increases in purchasing power. The fact that all these different interests ultimately came to support the creation of the. Coal and Steel Community was due to the abysmal state of the coal and steel industries of most of Western Europe after World War II. There was a clear interrelationship of economic and political factors. The ECSC would not have been possible had there not been strong economic pressures, and no solution had been found, except through political means.

The ECSC was immensely successful, and its success came faster than most of its friends anticipated. Its rapid progress would have been impossible without the grant to it of real power and authority, far beyond anything ever given previously to any international intergovernmental organization. This power included the right of the High Authority of the ECSC to tax coal and steel producers in all member countries. It included the right to fine individual firms for violations of its orders. It included the right to permit labor to move from one country to another. It included the right to close down marginal mines in any member country. The ECSC became what is known as supranational government, but supranational only in relation to specific objects and procedures.

Why do Belgians, Frenchmen, Germans, or Italians submit to such controls? They do so because the recognizable benefits are so great that the injury that would result from withdrawal is unthinkable. The recognizable benefits are a single market of 170,000,000 people for coal and steel products, greatly increased production and sales, less unemployment, better wages, and better profits. Put all these benefits together and it is not difficult to see why the "Six," as they are known, began to wonder if the same kind of desirable development could not be applied to products other than coal and steel. The obvious next step was to consider whether a common market for all the products of the Six could be developed - a common market that would bring to all sectors of the economy the advantages then enjoyed only by coal, steel, and related businesses.

The idea of a common market of 170,000,000 without internal tariff restrictions of any kind, as in the United States, was too revolutionary to gain immediate acceptance. Consensus grew, however, and by March of 1957 the Six were ready to sign the Common Market Treaty. A schedule for the progressive reduction of tariffs was designed to create a virtually free trade area by 1969, but by deliberate and carefully regulated steps. In 1960 the rate of increase in external trade of the Common Market countries rose 23%, its industrial progress increased by 11%, and its gross national product was 6.5% higher than in 1959. As Eric Johnston said, "In comparison, the other markets of the world are standing still." With such economic growth, the Common Market countries are speeding the process of tariff reduction years ahead of schedule.

As the process of tariff reduction accelerated in the Common Market, the rest of Europe wondered if it could long remain outside. Britain, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, Austria, Portugal, and Ireland formed a European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which was an attempt to secure some of the benefits of freer trade, without assuming the obligations and surrender of some sovereignty that goes with membership in the Common Market. It appears that such benefits can not be obtained so easily and the conclusion to be drawn from the Common Market experience is that some surrender of sovereignty is absolutely necessary. This is what the British now recognize and is the reason they are negotiating to see if it is possible for them to join the common Market without wrecking their Commonwealth relations. If the British and the other members of the Seven join the Common Market, it will almost certainly become the most powerful economic force in the world, with a unified market of 220,000,000 people, all in economically developed countries.

THE decision that we must face, with all the flexibility and perspective of which we are capable, is: What should bethe relationship of the United States tothe rapidly growing Common Market?

As we discuss and think about this vital issue, we should remember that we already have extensive ties to the thirteen countries of the Common Market and the EFTA. These began with the Marshall Plan in 1947, when the United States offered to help Europe rebuild its shattered economy. Some argued then that the United States could not afford the kind of money that would be necessary to put Europe on its feet. Others argued that we really had no choice because if we did not help, the Communists would gain control of key countries such as Italy and France. Still other Americans contended that with our great wealth and resources we had a moral obligation to help those who had suffered such terrible dislocation of their lives during the war. I think we must remember that in deciding to assist Europe to rebuild we did so because of a combination of economic and political reasons. From the political point of view, we wanted to prevent the spread of Communism, and from the economic point of view, we wanted to rebuild Europe so that it could once again become a great market for American products.

In order to allocate the Marshall Plan Aid, fourteen European countries formed in 1948 the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC), with the United States as an observer but not as a member. Thus we were closely associated with the political side of the first rapid recovery of the European economy, as we were closely associated with the economic side because we were supplying the funds for OEEC to allocate. But this was not enough because we believed that some form of political organization was needed to strengthen the military position of the West against Communism. In 1950 we participated in the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). We became a full member of NATO, rather than an observer as we were in OEEC. In 1960 we decided that being an observer in OEEC was no longer adequate and we helped create and then joined a new body known as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), whose purpose is to promote world-wide economic growth. We made it clear, however, that we were not willing to "coordinate" our economic policy with that of the other sixteen members. In other words, we agreed to work with other governments to try to promote economic growth, but we were not willing to be bound by anything that the organization might decide.

During the years since 1948, when the Marshall Plan began to operate, there have been many NGO's in the United States urging some form of closer economic or political association with the Atlantic Community of Western Europe. There also has been a great increase in international business ventures of all kinds. The pattern of the last hundred years continues, with international business and international NGO's leading the way, both in the realm of ideas and of practice - and governments following along more slowly. In January 1962 the culmination of much of the work of the NGO's was the Atlantic Convention in Paris, a convention of 98 semi-official delegates who had been chosen by . their own parliaments. This Convention has received little publicity, largely because it did nothing startling, nothing that most newspapers considered worth reporting except in a few paragraphs. The real purpose of the Convention was to explore whether there were any real bases for some form of closer political union between the members of the Atlantic Community. The most that these semi-official representatives of governments could agree upon was that within two years the governments should formulate plans "for the creation of an Atlantic Community suitably organized to meet the political, military, and economic challenges of this era." This may not sound very exciting, but the fact that members of both American political parties participated in this recommendation may lead to some very exciting proposals within a few years.

LET me summarize very briefly the situation as the people of the United States begin their analysis of the problem of what should be our relationship to the Common Market. First of all, we are already tied to Western Europe in international political organizations whose functions are both military and economic. These ties are the result of the hard facts of the existence of international Communism, but they also result from our conviction that they are to our economic benefit. That these ties also have strong ethical, moral, and cultural aspects is very important, although this is not always recognized. We may be in a position that is sometimes referred to as the "statesman's dream," which comes about when self-interest and ethics coincide.

President Kennedy has asked for an extensive liberalization of our tariff policy, primarily to make it possible for him to negotiate with the Common Market for an expansion of American foreign trade. At the same time, six Senators, from both parties, have introduced a bill known as the Trade Adjustment Act, or Senate Resolution 2663.

Each of us must now face for himself, with as much flexibility and perspective as he can muster, the issues involved in making a decision as to where we stand on the President's proposal and S. 2663. We have passed the point of debate unrelated to action. We now have to make up our minds concerning three alternatives: first, we can support the President and the members of Congress who are backing S. 2663; second, we can oppose them; and third, we can advocate some other course of action that will be better for the United States of America. I say we have to make up our minds because responsible citizenship does not permit us to avoid taking a stand on a problem as vital as this one. If we refuse to learn and to take positions on the basis of what we learn, we have no right to complain when things turn out badly.

The problem of the relationship of the United States to the Common Market involves some new issues for the American people. In January of this year our Government completed a series of tariff negotiations with the Common Market - negotiations that were quite different from those in which we usually engage. In modern times no one has ever confronted the United States, in tariff negotiations, with a power representing 170,000,000 economically developed people. We were dealing with a group of countries which now buys from us "more than $4,000,000,000 in industrial goods and materials and nearly $2,000,000,000 in agricultural products" - a total of about $6 billion a year, or a little less than one-third of all our exports. Joseph Krafft in the February issue of Harper's points out that in our negotiations with the Common Market countries they offered to reduce industrial tariffs 20% across the board and said, in effect, what can you Americans offer in return? Our only answer, under existing law, was that we could bargain product by product. When we turned to this kind of antiquated bargaining, our offer on one item was, according to the Common Market negotiators, "worthless." What the American negotiators had to try to do was to keep the advantages of our own restricted domestic market while, at the same time, securing a bigger slice of the Common Market trade. Any intelligent person will understand immediately the nature of this bargaining situation.

The Common Market negotiators knew that they were in a strong position. They were buyers of $6 billion worth of our goods each year and they knew that we wanted them to increase their purchases here. They also knew that the economies of their countries were developing at a more rapid rate than ours, which eventually would make them less and less reliant upon us. They also knew that we knew this. At the same time, there were things that they wanted from us - otherwise there would have been no bargaining in the first place. To make a long story short, we finally accepted reciprocal agreements to reduce tariffs on $600 million worth of specific products, which will still leave us with more exports to the Common Market than imports, or what is sometimes called a "favorable balance of trade." This must not be confused with our "unfavorable balance of payments." The United States imports about $15 billion worth of goods each year and exports about $20 billion worth, giving us a favorable balance of trade of about $5 billion. In pure theory, we should be taking in $5 billion more than we send out, but we are not dealing with pure theory. We spend abroad each year billions for military defense, and perhaps a billion in foreign investments. The net result seems to be that about one billion a year more goes out than comes in.

The relationship between economic and political factors is again apparent here. Our favorable balance of trade is an economic matter, although heavily influenced by world political events. Our unfavorable balance of payments results primarily from military aspects of political conditions in the world, but it is also caused by some economic factors, such as investment abroad. We should keep these facts in mind in taking our positions on the President's tariff proposals and on S. 2663.

I will close with two questions that each of us must answer for himself. Can the United States, facing the massive threat of organized international Communism as it does, and being determined to maintain its kind of life', including its standard of living, avoid very close association with the powerful Common Market of 170,000,000 economically developed people - a Common Market that will probably include 220,000,000 people before 1962 comes to an end? Is there any practical alternative to the President's tariff program and S. 2663?

Courtesy of the California Monthly

WALDO CHAMBERLIN, Dean of Summer Programs, has based his article on an address he gave at a New York conference of the National Association of Mutual Savings Banks in February. Dean Chamberlin came to Dartmouth last year from New York University, where he taught undergraduate and graduate courses in international relations, specializing in the United Nations. He earlier served with the U.N. Secretariat, was documents officer at the San Francisco Conference that established the United Nations, and during the war was with the State Department and the War Shipping Administration. A graduate of the University of Washington, he earned his Ph.D. at Stanford.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Reporter in Washington

May 1962 By ERNEST L. BARCELLA '34 -

Feature

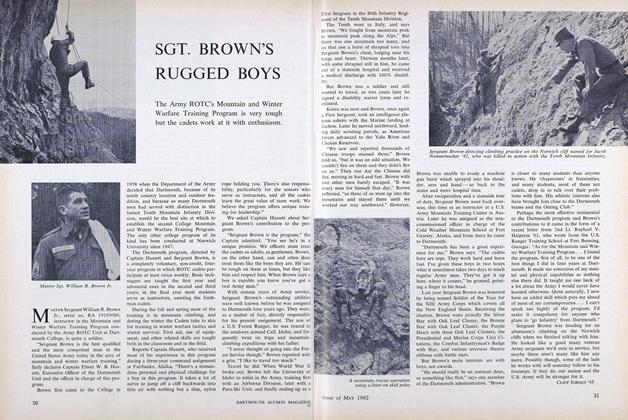

FeatureSGT. BROWN'S RUGGED BOYS

May 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dictionary's Function

May 1962 By PHILIP B. GOVE '22 -

Feature

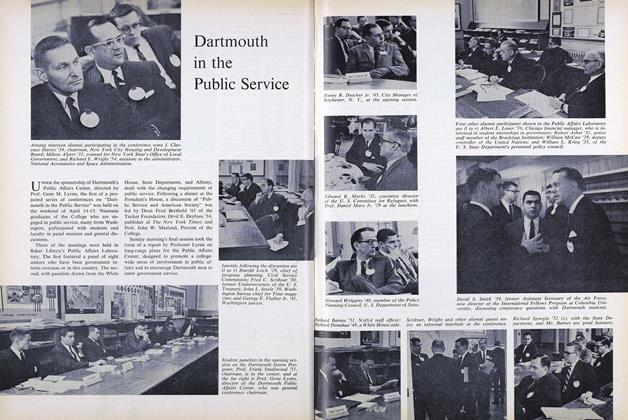

FeatureDartmouth in the Public Service

May 1962 -

Feature

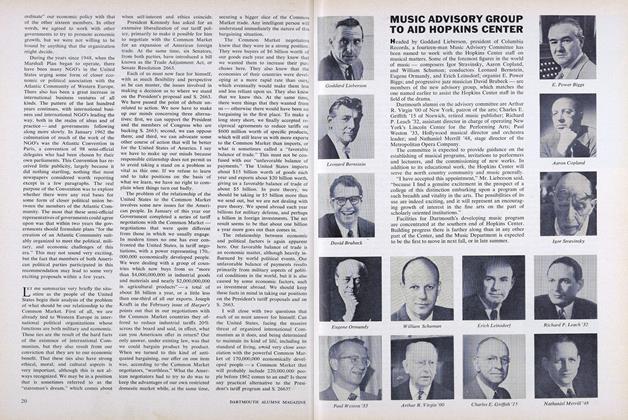

FeatureMUSIC ADVISORY GROUP TO AID HOPKINS CENTER

May 1962 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

May 1962 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSargeant Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureFaces in the Gallery

MARCH 1978 -

Feature

Feature1. Academic achievement

December 1987 -

Features

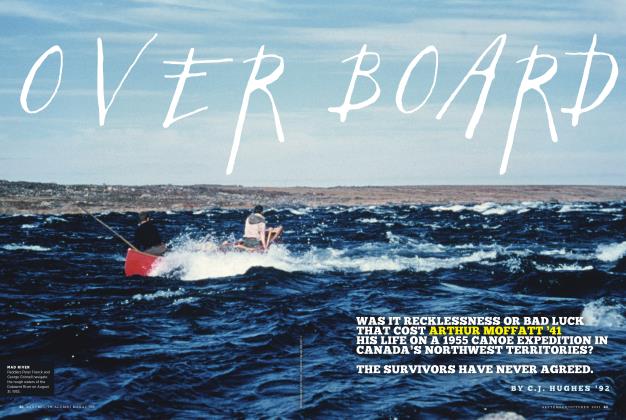

FeaturesOverboard

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2021 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureThe 50-Year Address

July 1961 By KENNETH F. CLARK '11 -

Feature

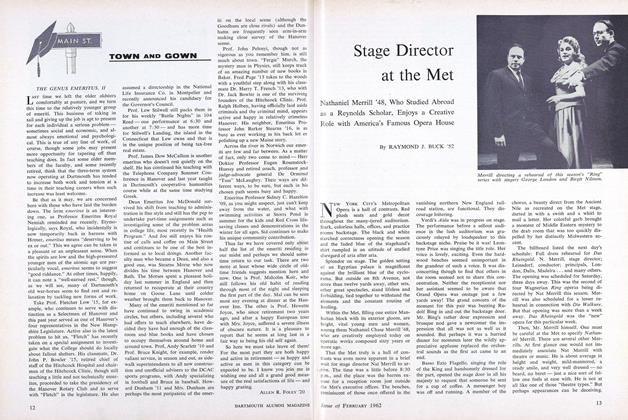

FeatureStage Director at the Met

February 1962 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52